Transcript

Martin

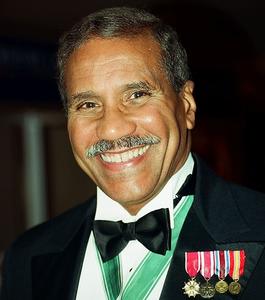

One of the things we like to do when we start is to do a voice check. This helps the transcriptionist to identify who is speaking. Let me just start off by saying I'm Paul Martin of the University of Virginia and I'm happy to be here to interview Togo West.

West

I'm Togo West, the interviewee, and I'm pleased to be in that position.

Chidester

I'm Jeff Chidester and I'm the research director for the Clinton oral history project.

Steiner

I'm Jessica Steiner, I'm one of the researchers for the Clinton oral history project.

Joyner

I'm Janice Joyner, I worked for Secretary West in the Department of the Army and Department of Veterans Affairs.

Martin

Why don't we go ahead and start with your introduction to not just the Clinton administration, but you also served the [Gerald] Ford and [Jimmy] Carter administrations? I was hoping to get that story of how you came to work for the Ford administration first and then the Carter administration.

West

You have a suggested question somewhere in the list in the back of the book that says, "Did you find that your previous positions in the Department of Defense--" presumably referring to my time in the Carter administration-- "helped you when later you were Secretary of the Army?" The answer is, probably. But the one that helped the most was that after graduating from law school and clerking for a year in New York, I went on active duty. It was the time of the Vietnam War. I was an ROTC [Reserve Officers Training Corps] graduate from Howard University, as had been my father before me, Army, and was commissioned as a combat arms officer, field artillery, upon graduation from engineering school.

But then under the program you became a JAG [Judge Advocate General] officer if you went to law school, took the bar, and came on active duty. You went from a two-year commitment to a four-year commitment. In the process, all the time you spent between commissioning counted against your then eight-year military service requirement. So by the time I finished the JAG Corps, I was through with my military service requirement. All four of those years were spent in the Pentagon. Those helped me more than anything. For one thing, I knew my way around the Pentagon way better than any of the countless number of aides-de-camp and others who were assigned to guide me around as Secretary. I knew all the shortcuts.

But anyway, when I finished undergraduate school--While I was in law school at Howard, there came a time when I was a summer associate at Covington & Burling. All those early things played a role in what happened later. I think it's true of all of our careers: the things you do early end up having influences later. I'll just make this very quick because you don't want to spend a lot of time on this.

After clerking as a summer associate at Covington, I went up to New York to clerk for a federal judge in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. The judge's name was Harold R. Tyler Jr., "Ace" Tyler, himself a World War II veteran, a Republican, appointed during the administration of John F. Kennedy during the days when Presidents nominated, but they made deals with the Senators from the various states, whatever the party was. Tyler himself had a record that would have attracted Kennedy. He was one of the first three lawyers to serve as head of the Office of Civil Rights in the Justice Department. He was in the [Dwight D.] Eisenhower--He was the second one, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights. He headed that office at the time of Little Rock [Arkansas] and some other things. And he had obvious commitment to providing opportunities. There weren't that many judges taking young African Americans into clerkships in those days.

I mention that because some years later Judge Tyler--not a lot of years later--but why don't I take it in order? I clerked for him for a year, returned to start on active duty. The first eight weeks of Army JAG is, of course, of some significance to you from the University of Virginia because you have housed the Army JAG School for a long time. I can remember that you've housed it in three different locations, all of them corresponding to the location of the law school, which has moved about from time to time. When I was there, the law school and the JAG school were more central on the campus. So I was there for eight weeks.

During those eight weeks, there came a time when we received our assignments. My first assignment--My family was still in New York, where I'd been clerking--was to go to Fort Ord, California. Now, for the JAGs in those days that meant, since that's West Coast, you're going to do a year there to prepare you to jump off to Southeast Asia. You do a year there, short tour, and then return for a two-year assignment basically as much to your liking as the JAG Corps could make it, and then you'd be at the point to get out or decide to stay in. That didn't happen with me.

Just before I was due to meet my wife and leave for the new assignment, I got a call from career development at JAG, and they switched me to an assignment in the Military Justice Division, in the Office of the Judge Advocate General at the Pentagon. I went there and six months later I was assigned to work for a young Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Office of Manpower and Reserve Affairs. So, essentially, I spent that final three and a half years of a four-year commitment as a young assistant working in the office of one of the Assistant Secretaries of the Army and getting to see a lot of the policy interplay, particularly in the personnel field.

My areas were drugs--There was suffering from that--race relations, and all the sort of special issues that an army that is both garrisoned and deployed is facing. Remember, we're talking '69 to '73, and the Army is in Germany in a much larger configuration than now. It has a four-star commander just for the Army in Heidelberg and several three-star commanders. Eventually Colin Powell would get one of those three-star commands years later as a corps commander. It had its deployment of corps things, career, and even greater strength there. And it was deployed around the world. Well, a garrisoned army gets into a lot of trouble, and the issues that were affecting us here in the United States--race and drugs--were big ones. So I worked those projects for four years. That had a big and useful impact.

I went back to Covington for the two years after I left the Army. During those two years, a bunch of things were happening in American society. We're talking about 1972 to '74, or was it '73 to '75? The big thing was the implosion of the [Richard] Nixon Presidency. There came a time when the Saturday Night Massacre occurred. Richard Nixon's then Chief of Staff, an Army four-star, not on active duty, but between assignments, by the name of Al [Alexander] Haig, calls up the Attorney General, who at that point is Elliot Richardson, who has already had two other Cabinet posts in that administration, and says--He was briefly Secretary of Defense about six months, and then before that he was at HHS [Health and Human Services], HEW [Health, Education and Welfare] in those days. He says to him, "The President wants you to fire Archibald Cox," then the Special Prosecutor, but without Special Prosecutor legislation. That hadn't occurred yet, so he was an appointee. The President had the power and the authority to do it. Richardson had the authority to do it, and as you recall, he declined and said, "I quit."

Al Haig calls up the Deputy Attorney General, Bill Ruckelshaus--he of environmental fame before and after--and says, "You're now the Attorney General. Your Commander in Chief wants you to fire--" and it repeats itself. Ruckelshaus says, "I won't do it and I quit." And then, in an action that had an effect on a later Supreme Court nomination, Al Haig calls up the Solicitor General, who is Bob Bork, and says, "Hey, the President wants you to fire Archibald Cox. You are now the Attorney General." The other two have gone away. It's still Saturday. Bork explained later that his view was the President was entitled to do that, and all that the Attorney General was supposed to do was carry out the instructions. He did. People later on didn't see it that way, and he never became a Supreme Court justice.

Nevertheless, Cox is fired. That leads to Nixon's eventual resignation. There is the first President, and only President, to serve who was never elected in a nationwide election, either as Vice President or President, Gerald Ford. Gerald Ford wants to reconstitute the Justice Department. He appoints William Bart Saxbe first, the Senator from Ohio, who had been Ohio attorney general at one point. Saxbe didn't stay long. Then he does something that warms the cockles of every law student's heart in America: he picks Edward Hirsch Levi to be Attorney General: at that time president of the University of Chicago; former dean of the law school; former, for five years, senior careerist in the antitrust division at Justice; learned in the law; above political partisanship. He was last a Democrat. He'd been a Democrat; hadn't registered in years; respected by everyone; as smart as could be; nonpolitical, and yet not a babe in the woods either; wonderful administration.

He decided that, as part of resurrecting the Justice Department's morale, he'd find himself a federal judge who would be willing to give up his career, tenure, and become the number two at the Justice Department. He picked a little-known, but not completely untalented, United States District Judge in the Southern District of New York by the name of Harold R. Tyler Jr. who eventually, after he had been sworn in, called me up and said, "I have a big office; it's right next to me; you can come and sit in it. We'll have great fun; we'll run the department." I said, "Judge, I'm a Democrat." He said, "That's OK. I can work it with the White House." And in those years you could; those days you could. Each successive administration, whatever its orientation, has become harder and harder about that. But the Ford White House did allow me to be appointed Associate Deputy Attorney General, so I ended up in the Gerald Ford administration in a pattern that would repeat itself: didn't know him, had never been part of his inner circle, nor of any President that I've ever served.

Martin

You had said that it wasn't a problem for the Ford administration to bring you in as a Democrat. Can you talk a little bit about that interaction, just to give us some historical basis for it?

West

It was a problem, but it just wasn't as big a problem as it would have been in successive administrations. That is, yes, you had to be cleared by the White House. It was not a PAS [Presidential Appointment with Senate Confirmation] appointment, but it was a PA [Presidential Appointment]. It required approval in the White House personnel office, and it was essentially an appointment by the President. It's the one on top there. [referring to a document]

It did require going through the process. There were fewer papers, but there were papers. There was a clearance process, and it didn't happen overnight. It took six to eight weeks. I think I was over there shortly after Tyler started, and yet this is not signed until July. Well, I was over there in April, and this is signed the 20th of July. So it took that long to get it cleared. But somewhere there is a plaque or something, or a picture that says my time was April to April, because I only stayed a year.

So the answer is yes. There was a process, and it did require Judge Tyler to go talk to the White House counsel, the deputy counsel, who at that time was Carla Hills's husband, Rod Hills. He had to say, "This is someone important to me. Get the Attorney General to support him." But it got done. Didn't require a bunch of Senators to call up; I didn't have any Senators to call up anyway. I was here in the District. So there was a process, but it simply was not as difficult.

And to say that these spots weren't normally reserved for Republicans would be to give the wrong impression. There were two Associate Deputy Attorney General slots working for the Deputy Attorney General. The other one was filled later on by a Republican. I don't think that I know of any other Democrats serving in the Attorney General's office. He had a bunch of assistants or special counsel. Well, a fellow who ended up the owner of the Chicago Tribune, Jack [Fuller], wrote a book--I'll think of his name. But anyway, I think he was a Democrat. So to say that it was not a problem is a misstatement by me. It took some doing, but it wasn't nearly as painful as it would be now. It would be quite difficult, I'd assume.

Martin

Before I interrupted, you were getting onto the Carter administration.

West

The one thing I would say about that is, in that year, I mentioned that what happened is that under the Deputy Attorney General--who had essentially responsibility for running the department while the Attorney General oversaw it and did lots of other things--the guy who had my job basically kept an eye on the civil part. The Civil Rights Division, the Civil Division, Lands and Natural Resources it was called then, which was environmental and also ownership of U.S. properties and parts and the like, Interior Department stuff, tax division. But the criminal division would have been under the other associate deputy. Also liaison with the organizations, the other departments--FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation], DEA [Drug Enforcement Agency] was there then, INS [Immigration and Naturalization Service] was still there, Office of the U.S. Attorneys, and the like.

So we needed to get the other one filled and we did, and we took a young prosecutor from the Southern District of New York. He had gotten himself quite a name. He had clerked the same year I did in the Southern District, but I had never met him. He had convicted a Congressman in the Abscam trial, got big notoriety. His name was Rudy Giuliani. So there are all these Republicans around me, and we worked closely, because of drug interdiction, with a guy who was on [Nelson] Rockefeller's staff, who was then the Vice President at the White House, and who came over to see us quite a bit. He was a very sharp guy, also a Republican--big, tall guy--and his name was Richard D. Parsons. Parsons is now the CEO [chief executive officer] of Time Warner. Both those guys ended up at Patterson Belknap, which was Tyler's partners years later, as did I. So those things have a lot of effect on you, on your later life.

I went back to Covington & Burling after one year. I had told the judge I would need to. He had said, "Hang around. We're a year away from an election. See who wins. Maybe we'll stay in. Make your decision then." But I had been very late in getting started on my career in the law, and it was important to get back. As soon as I'm back, this guy, a Democrat, comes out of the woodwork. He runs around; he tells people, "My name is Jimmy Carter. I'm running for President." I was not involved in his campaign. He gets elected.

Cliff Alexander was becoming Secretary of the Army and knew my wife's family. He asked me if I'd have any interest in coming into the administration. At the time, I told him I'd think about it. He wanted me to be Assistant Secretary in charge of the very office in which I had worked as an officer, Army Manpower and Reserve Affairs. I called a fellow who had just been a partner at Williams & Connolly, just taken a job--Williams & Connolly used to be right over there--had just taken a job as the chief of staff to Harold Brown, the Secretary of Defense. The title in those days was called The Special Assistant to the Secretary--capital "T" on the "The," which the military do in the Pentagon quite often. It's not Judge Advocate General; it's The Judge Advocate General. The Special Assistant--and it's actually The Special Assistant to the Secretary and Deputy Secretary, both those options together, very powerful. It was first created when Mel Laird was Secretary of Defense, so it had a little history.

Anyway, this fellow had just taken it on. His name was John Kester, back over at Williams & Connolly now. John was the young Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army that I had worked for as an officer. Once again, what happens to you earlier in life tends to come back, and sometimes it doesn't take long to come back. I called him up and said, "John, this is what I've been asked to do. What do you think?" He said, "Well, I didn't know you were willing to come back into the government. Come on over." So the long and short of it is that he introduced me to [William] Graham Claytor, who was about to become Secretary of the Navy and who had been a partner at Covington. I had known him and had worked on some cases for him. He had been president of Southern Railway before that. And I was introduced to young guy who was going to be the Under Secretary and with whom I would have lots to do in later years by the name of R. James Woolsey. So Claytor, Woolsey brought me in as the general counsel of the Navy. That's how I got into the Carter administration. I did that for two years.

There was a job I held that's not mentioned in the stuff you have there, and that is the next one I'm going to mention. My third year there--It would have been '77, '78, part of '78, part '79--John Kester left to go back to the practice of law. The Deputy Secretary, who was Charlie Duncan then, who later went over to be Secretary of Energy after James Schlesinger, and Harold Brown, Secretary, interviewed me and asked me to take that job. So I had a third job, or a middle job there, as the Special Assistant to the Secretary and Deputy Secretary. That's the next job that I had that, as much as anything, had a hand in preparing me for later, because in that job I saw everything that went to Harold Brown, which, incidentally, was a real chore because Harold Brown was a genius. His mind worked lots faster than anybody else's, especially a lot faster than mine. He's a nuclear physicist, a PhD--and he'd gotten his PhD at a very early age--very young director of the Livermore Lab in his early 30s; very young Secretary of the Air Force in the Kennedy-[Lyndon] Johnson years; and a very young DDR&E, Director of Defense Research and Engineering, in those days, when that was the third-most-senior job in the OSD [Office of the Secretary of Defense].

So that's how I got there. I did that for a year. I ended up then as DoD [Department of Defense] general counsel for the last year. It is during that period that I met a young member of Congress who was very liberal, out of place, on the House Armed Services Committee, by the name of Les Aspin.

Martin

It struck me, your story about how you got involved in both the Carter administration and the Ford administration could be unique for that time, or it could be common--the fact that you're a political appointee but not really connected to either administration in terms of campaigns or old friends or contributors. Did you get a sense that this was a normal thing at that time?

West

What I thought was that my presence in the Ford administration did not strike me at the time as any more unusual than Dick Parsons' presence or Rudy's presence, because neither of them had been really involved in the Ford--Look, Ford didn't have a campaign.

Martin

Sure.

West

He didn't have a campaign to be Vice President either. He came over. So what was unique was the time. We all thought that what happened with Richard Nixon, and the President leaving under those circumstances, was extraordinary. But the many different ripples throughout not only American society but American government occurred and had effects in different ways, not all as profound as we tend to think about. But even the little ones such as, how do people end up in positions? At that point, there may even have been a kind of--He was ramping up, in the middle of a Presidential term, basically to complete a term and hopefully to prepare for the next one.

What he needed more than anything was--We use this phrase so often, but I think it's--kind of "pulling people together." So it would have been natural for Judge Tyler to turn to his old law clerks. In fact he didn't just bring me in as one of his two associate deputies. He brought both his law clerks who were with him at the time, plus the two he had hired. That's understandable. In fact, one of my duties was to keep an eye on those folks. They were on my staff.

So it didn't feel unusual for me. If you ask me to look at it in hindsight, I'd say it was an unusual time, but in more ways than people normally think about it. Not just in the fact that we're going through the trauma of a President gone, a new one is in. Is he going to be pursued? He's got to be pardoned by Gerald Ford. Remember, that cost him, people thought, votes? Actually you don't remember, but you've read.

Martin

I was alive.

Steiner

We weren't.

West

It was unusual in lots of different ways. In my case it was unusual in little ways. But I think it all was a function of the times more than anything else, so I ended up showing up in other administrations.

I grew up in Winston-Salem, North Carolina in a very real way. It's not just that I was born there and left. I mean I grew up there. I went to elementary school there. I spent eight years in a Catholic elementary school, four years in the public high school, segregated, where my dad was vice principal--became principal, but happily after I had graduated. An only child of teachers--What that meant was that every summer we packed up and left town. We tended to come here because the teachers then were paid then, as they often are now, on longevity and academic credentials. So they go off every summer and work on their master's degree. Dad would go to Penn State; Mom would go to the Teachers College at Columbia; and they'd stow me right here with grandmother over in southeast Washington, so I spent most of my summers here.

In many ways you can never be a true Washingtonian unless you're native. I'm not. I'm the only generation of my family that's not. Our girls are from here. But when I graduated from Howard Law School in '68, I was already married. I had married my law school classmate at the end of our first year of law school. She had come from Cincinnati. Her dad was in the Johnson administration, so she was living here. Her father worked for Sarg [Sargent] Shriver at the poverty program.

Now, he's an interesting story. He had started, as a member of the council in Cincinnati, a little operation in which poor people actually took control of some of the issues that were being decided. They called it a "community action program." Sarg wanted to include that, so he brought him to Washington. He became one of the three assistant directors in charge of CAP, Community Action Program, which had the community action programs in LSP [Land Stewardship Project], the stuff on the Indian reservations, Head Start. It had a bunch of other things, including legal services.

They were here, and she came here to go to Howard and be with her parents. We got married, so from '68 on, we were essentially residents of Washington, D.C. We were part of the permanent culture here, not because we came here for an appointment but because I came here to go to school in a city where my dad's family already was. She came here because of her dad. So we formed associations. I mean, John Kester, when he left the administration while I was on active duty, didn't leave town. He stayed and practiced law. I didn't leave. In fact my whole life has been--We live in the same house, since 1984. I just get up and go to work in a different office.

So, to some extent, there probably is around a body of people--Let me give you an example: Jim Woolsey never went anywhere. He's from Tulsa, Oklahoma. He had been working on the Hill at one point. He's Under Secretary of the Navy in the Carter administration. He goes back to practice law at Shea & Gardner. Then one day you're talking to him and he disappears. And you can't find him until you see him on a TV broadcast from Arkansas and the President is just naming him CIA [Central Intelligence Agency] Director, and then he disappears again, because that's what the CIA does with their Director. So I don't find that so unusual. There are folks, like Madeleine Albright over at Georgetown when she's not in government--Now I think it's a little unusual, at least as I matured in my profession, to not be involved in some of the campaigns.

There's even a funny story that when my nomination finally showed up on Bill Clinton's and Hillary [Clinton]'s joint desk--They tended to be reviewing those nominations jointly at the time--It is claimed by one of the guys who says he advised the President on stuff like this, that he said, "Who is Togo West, and what has he ever done for Bill Clinton?" Of course, the answer to the first, by those gathered there, was, "Don't know." And to the second is, "As far as we can tell, nothing."

Of course that was all Les Aspin. It's not what most people think of in terms of how you end up in an administration. I believe it happens more often than not. I would love to tell you that it has something to do with making selections by merit. I'm not so foolish as to claim that. I am willing to say that at least part of the explanation has to do with the fact that when you come and you put together an administration, at some point you talk to people, you have some advisors around. You notice all candidates do it. They always wind up with some group that actually used to be here, whether they're in Arkansas or in Texas or down at the Pond House in Georgia or wherever--Kennebunkport, I guess, California--and who tend to know folks. And you do say, "Who have you got who actually would know this area?"

Now, Secretary of the Army is unusual, because that tends to be every car dealer in America who used to serve or went to the Academy or anything and put big money in and who say, "Hey, my time, President, and that's the job I want." So a lot of times--

Martin

It does tend to be more ceremonial sometimes.

West

Not so much ceremonial as it, like ambassadorships, are what people outside the government who have made contributions think should be used to pay them back.

Martin

Let's jump for a second because, Jeff, you had some questions about your time when you were the lead government-affairs official for, was it Northrop?

Chidester

If we go back, you joined--

West

I can get you there. I'm done there. I don't go back to Covington.

Chidester

You go to Patterson.

West

Where Judge Tyler, Rudy Giuliani, and Dick Parsons are all partners and where they say, "We want you to open up the Washington office." I open up the Washington office and do it for nine years. Then I'm asked to join Northrop, and that happens because of people who affected my life earlier.

My second year in private practice--The office was right there on Pennsylvania Avenue, just two blocks down and over--Jim Woolsey called me up--He used to be at the Navy--and he said, "What are you doing?" I said, "Well, you know." He said, "Would you like to be on the board of something called the Aerospace Corporation?" The Aerospace Corporation is one of the big nonprofits that is attached, FFRDC, Federally Funded Research and Development Center. Its big contract is with the Air Force. They're in El Segundo. Great place. I wish I were still on the board.

This is this crowd that I joined [showing more pictures]. Incidentally, one of the board members is Gerald Ford. That was a very young-looking Woolsey; this is Cornelius Roosevelt; this is Hedley Donovan; this is one of the last CINCSACs [Commander in Chief, Strategic Air Command]; this guy right here is the four-star General Russ Dougherty. The thing about Russ is, he is the father-in-law of--I'm trying to think of his name, who was SACEUR [Supreme Allied Commander Europe], also an Air Force general. So anyway, Herb York, formerly of the Times.

So I went on this board, which got me into the aerospace community. Part of the reason, of course, is defense, my undergraduate engineering degree, so they all thought it was related. Reminds me of a funny story I'll tell you when we're not on about a conversation I had with Harold Bromley, who asked me to come to the Pentagon.

But in the course of that, I got to know a bunch of the, obviously, senior people at Aerospace, one of whom ended up leaving and going to Northrop. At some point he called me up and said, "When is the next time you're going to be out for a meeting? I'd like you to come meet some of the senior people at Northrop." Kent Kresa had just taken over as the CEO. Tom Jones, the former CEO who really built it into a big thing, was getting a lot of criticism over some sales to South Korea. The then head of the Washington office, who is still in the business, Stanley [Ebner]--Anyway, he now does work for Boeing--was leaving after ten years, so they offered the job to me.

Chidester

You were in private practice for about ten years.

West

It's actually nine. Ten is just the round number.

Chidester

But you're still plugged into this network--

West

Still have a security clearance, which in the defense business, the national security business, is the indication that you're still doing something.

Chidester

Did you have intentions to go back into public service, or were you satisfied with--

West

I think, at that time when I first left, having been general counsel of DoD, I'd only had a chance to be general counsel of DoD one year, and that, for a lawyer, was a really great job. As I look back, I don't think of it as necessarily the most important, certainly the most senior. I wished I had time to do it longer.

So I thought, Ah, well. Remember, we in the Carter administration maybe should have been able to read the writing on the wall, but I think most of us thought, Aw, come on. The guy, sure, he was Governor, but he's an actor. He's not going to beat Jimmy Carter, graduate of Annapolis and all sorts of great stuff. So we found ourselves unceremoniously dumped out on the economy with a feeling that there's some things left to do. So I think most of us from the Carter years thought we might go back. But what happened, of course, is that Ronald Reagan gets reelected. So now it's four years gone and another four to go.

Then I remember my wife and I left and took our two daughters to Europe--We thought it was time for them to see Europe--for two weeks. At the time, the then Governor of Massachusetts was leading George [H. W.] Bush, the incumbent Vice President, handily. When we came back, the race had flipped in just two weeks. I think it was the grainy photos of the guy. So now it's 12 years. By the time we got into the Bush years, I'd pretty much abandoned the notion that I'd be back in government.

Chidester

But you're part of this network that is almost a network-in-exile that is ready to go back into government. A lot of these people are thinking that with the next Democratic President, they'll likely take positions in Defense.

West

When I went to Northrop, my wife and I thought that I had made not just a career change but a final career change. She had been in the corporate world all along. She had never been a vice president. I went in as a senior vice president. To my shock, it was much better compensation than I had even as a partner in a law firm. Modest size; Patterson Belknap was pretty good size then; it's bigger now. Our daughters were, by then--Tiffany [West Smink], when I started Northrop, was finishing Harvard and was going to start law school at Yale. Hilary [West] was just starting college at Connecticut College. It was still useful to have the income. Actually, at that point, when we started at Northrop, I thought, Government is over and out. Not just a decision that I don't want to; it just didn't seem that it was practical to think it would happen anymore. It just was done.

I remember the first time somebody ever said, "I want you to meet the next President, Bill Clinton from Arkansas." I thought, Oh, well, sure.

Chidester

This is what I was getting to. I'm interested to hear not only your perspective but what you sensed from this network. Around '90, '91, you start getting the Presidential campaign in its early stages, and you've got guys like Bill Clinton coming up. What did you hear about him? What were your impressions? What did the network think of this guy?

West

I wasn't as plugged into the network as you might think. The reason is that it has never been that interesting to me to get involved in the organizing and back-and-forth of the political process. I'm happy to do some things, but I didn't want to go to meetings. I didn't want to even get together and chew the fat. It's not that I got invited and said, "I won't do it." I just never made the effort.

So, for example, when everybody was gathering--Let's go back to Jimmy Carter--and going down and advising him and Jim Woolsey and all those guys--The benefit for me was that I knew people who were doing it, but I wasn't one of those doing it. Same thing with Bill Clinton: I knew people who were doing stuff with him, who were getting more and more excited about his candidacy, but I was sort of watching from afar saying, "Well, if he can do it."

Remember, my job in those days was to advise my CEO back in Century City as to what was happening around Washington, the same question you asked me. What are you hearing? What's the scuttlebutt? What's going on? But I wasn't really plugged into the network that much. I had friends who were. I talked to them on the phone. They'd say, "This is what we're hearing, and this is what we're doing."

Chidester

Your friends in the defense community--

West

One of my friends was the chairman of the DNC [Democratic National Committee] at the time, Ron Brown. Right here in Washington, sitting over at his law firm doing all sorts of stuff. But I never saw that much of him. He just was someone we'd known for years. It was as if we watched more than participated.

Martin

As the campaign progresses, you have the issue of the draft with President Clinton. You have other figures who are potentially going to enter the race. Was there a favorite among the defense community? Was the defense, or military, community put off by Governor Clinton at the time?

West

Well, if you mean the defense Democrats--and I did consider myself part of that group--frankly, by then--Remember, it's been 11 long years; we're in the 12th year. I think all elements of the Democratic community were saying, "Can he win? If so, we're for him." Remember, some 22 former generals and flag officers wrote that letter for him saying, "We think he's perfectly capable. We're not at all put off by all this stuff about his so-called ‘unclear draft'" and that curious letter he writes. Back and forth and all that stuff. "We think he would be fine." Frankly, I just think that the feeling in the Democratic defense community at the time was, if he can win, they're inclined to support him. The theory being--I think this is true of every specialized community within political circles--we'll get him in; we'll train him. It never turns out that way. But you can see us all sitting around saying, "Sure, we know what he thinks he thinks. We'll tell him what he thinks when he gets here."

Martin

You're some hick from Arkansas--

West

He did some very interesting things. It was clear very early on that he wasn't just a hick from anywhere, I remember. That's where the [J. William] Fulbright fellowships come from, Arkansas. So they're not all that hicky out there.

Martin

You don't actually become Secretary of the Army until '93--

West

And late in '93, November.

Martin

What are you doing between the time that Clinton is elected and--?

West

Thought you'd never ask. There I am on the board of the Shakespeare Theater. That means that they have four productions a year, and there's always a premiere. Listen, not all business gets transacted in business circumstances. So there I am and the practice still is--because I was at Northrop and I could sponsor a lot of these things--The practice is that the various contributors have a big dinner just before the production. Then you go in. That's the premiere night, and then you come and stand around. So there are always people invited, the dons of the Hill, the barons and baronesses.

One of them was the then chairman, and it happened--surprising thing--For decades it was chaired by these southern conservatives, and this liberal from Wisconsin becomes chairman of the House Armed Services Committee. At the same time, Sam Nunn is chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and Les Aspin used to make every one of those premieres. He liked coming to the Shakespeare; he liked the Shakespeare plays. He'd always bring one of his dates; he had a bunch of dates. I'd see him there and I'd say, "Mr. Chairman." I'd shine him up and rush back to my office in Century City and fire off a fax to Kent Kresa that said, "I just talked to the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, and this is what he said--" The message was always the same. He'd say, "Togo, we're going to kill the B-2." That was the big thing. He was killing the B-2, and I was trying to get the B-2 through.

There came a time after the election--What was I doing after the election?--when I went there, and Aspin was there. I had some guests there, dear friends for a long time from Covington. We came out for the intermission; we're standing there; I'm talking to them. I see Aspin; I think, I need to try to talk to him at some point, but I'm talking away. As I turn, he's there. He's come over with his date, so we're chatting. I think, OK, speculation out there is who's going to be Secretary of Defense? We know the President is going to name that package early. He always does the national security cluster early because the world wants to know who it's going to be. They get them in right on Inauguration Day.

So I think, I'm going to be clever. Now, I know this is not going to sound clever to you, because it didn't sound favorable to me when I said it, but you do what you have to do. So I turned to him and I said, "Mr. Chairman, what are you going to be doing come spring?" Isn't that clever? Oh man, that's so subtle. And he says, "I don't know, Togo." I think, Eh, wrong answer. He's supposed to say, "You jerk, I'm the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee. I'm going to be kicking you and your B-2 around just like I've been doing." He didn't say it, so I'm composing my answer on this.

He said, "I have a question for you. Is Northrop paying you so much money that you wouldn't go back into public service?" Remember the question you asked me earlier? I had completely stopped thinking about serving in the government. After a while you don't think about it. Eleven years is a long time. As far as for me at the time, I had no answer. I found myself on one of my rare occasions, I was speechless. I looked to my wife and my friends; they're not there anymore. You know how you can sometimes find yourself in situations, and it seems as though suddenly there's a spotlight on you and you're standing there and out there is black. Well, there it was, just Aspin and me here in the spotlight. I'm trying to think.

So I fumbled something like--I can make it sound much smoother now, but it wasn't smooth at all then--"Mr. Chairman, Les, I'm like you: I consider there's nothing more noble a person can do with his or her life than public service." Something like that comes out. He says, "OK." That's the end of that conversation. Eventually Aspin is picked.

On Inauguration Day I'm out along the parade route at one of the parties that they give in the banks so you can watch them go by. I call the Northrop switchboard here and talk to my receptionist because, though businesses in town here are closed, Northrop is out there in Rosslyn. So we were open. I asked her, "Do you have any messages for me?" She said, "Oh, Mr. West--" She's all atwitter-- "Secretary Aspin just called." "What ‘Secretary Aspin?'" Then I remembered, of course, they got the package through. And she said, "He wants you to call him."

So eventually I got back to an office. I called him. That was before there were a lot of cell phones. I go over; I see him; I see his chief of staff; and they've decided that they want to send--He's got to get his "big seven" over: that's the Deputy Secretary, two of his key Under Secretaries--or three, I forget what--and the three service Secretaries or something like that. So he's sending me over, Secretary of the Army. That's the way he did it.

Now, there's another little piece in between that I forgot: that is, around that time, also, I started getting calls from a woman who was part of the Presidential transition team, the part that was doing personnel. Her name was Pat Irvin. She ended up as a Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, but in those days she was part of the senior effort to find talented people for DoD. But she wasn't calling me about me; she was calling me to get my input on various people. Eventually she began to ask me about women--and minorities too. But just people in general. She cleared names with me. She'd say, "What about this person?" I remember she used to call me every Sunday afternoon at home. I guess that's because during the week it's hard to find me. So, over time, I had lots of conversations with her, the only contact I had with the Presidential transition team.

The last time she talked to me she said, "OK, let's talk about you. What should you do?" I said, "I don't have any aspirations this time around," because I hadn't thought about it. She said, "Yes, but what should you do?" I said, "Well, I don't know. Probably a service Secretary, but I couldn't be Air Force because of all the work Northrop does." That was as much of an early conversation as I ever heard. I didn't think much of it, but it went from there to the--The timing is, the Aspin conversation is way earlier. Then Clinton comes to town. He starts talking to Patricia. You'll see her listed as a DoD Deputy Assistant Secretary. Then suddenly there's--This is all in December. Then there's the inauguration in late January.

Now, after that I heard nothing. I received no papers to fill out. This is always the signal that you're actually seriously being considered. From time to time I'd see stuff in the press. It wasn't even moving enough for me to talk to Kent Kresa about it. You're always going to tell your CEO, but there just wasn't anything. Maybe in February or so there might have been a mention or two of it, a couple of weeks later. Then it went away. Started hearing other names. Nothing happened until late July. Late July is interesting around Washington. It's the last period before the really serious vacationers go off to Martha's Vineyard or wherever, and Vernon Jordan called me up.

Now, Vernon is someone I've known for a long time, off and on. Even then we considered ourselves friends. He knew Gail [West]'s father. That's Ted Berry. Those were old-line civil rights guys. I used to go out to Century City several times a month for meetings. I had gotten on the plane to go out there, and when I landed at LAX [Los Angeles International Airport], there was a message to call my office, and I did and she had two messages for me. Vernon Jordan had called and wanted to know if he could see me the next day. She said she had already told him that I had just gone to LA [Los Angeles]. He said, "Well, maybe if I called him."

And Ron Dellums, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, had called. He said he wanted to see me, and she told him the same thing. He said, "Well, maybe--" I forget what his message was, but my message to her was, "Call him back. Tell him I'll be there," because I'm the Northrop guy. At the time, Vernon Jordan was very close to the President of the United States. I don't know what he's calling about because I'm not in the mix anymore, I didn't think. No, I'm sorry. I had gotten a couple of calls from personnel asking, "Would I consider being Under Secretary?" I said, "No, I wouldn't do that," because they'd begun to fix on somebody else.

Martin

There's still no Army Secretary, right?

West

Right, and it's taking a long time. They finally got a Navy Secretary in June but because they had to. What was it? Tailhook had reached out and claimed another victim, and it was the holdover Secretary, I think, or something like that. They had to get a Secretary in. That was John Dalton. Then they had wanted to get a woman in, so they closed on Sheila [Widnall] sometime in the summer too. They had John Shannon, a holdover from the Republican times, who had been Under Secretary. He got himself in trouble over at Fort Myer, in the commissary shop. I still don't understand that. So they finally were forced to move on that. But up until then they were just dawdling. It was because they were going back and forth. They had some guy they wanted to put in one of the three jobs. The military didn't like him because he'd been associated with the President's gay initiatives, and they were real uneasy about what the President had in mind there.

I wasn't hearing a lot about it, and it wasn't clear what I was coming back to Washington for. I just knew I was coming back. So I went by Northrop. I told Kent Kresa's secretary to tell him that I'd gotten a call from these two guys and, if nothing else, any time I can go in and see the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, I'm going to do it. He understood. I took the redeye back. I went to see Vernon, who said, "The President is going to go with you for Secretary of the Army." I said, "Are you serious? I had heard it was going to be So-and-So." He said, "The guy doesn't know his way to the--It's going to be you."

Part of this, I think, is that Aspin had gotten tired of waiting. I'm trying to recall if I had a call from someone who said, "We're going to make a press." But they were always real careful about committing themselves, the people around Aspin. And I never called them. I was experienced enough to know that would have been a waste of time. You don't call people up and ask them. You never get through, and you just embarrass yourself. What I learned after is that Aspin had decided to put on a full-court press. He had called Vernon or had someone call Vernon. He had called Ron, because Ron, the House Armed Services, had nothing to do with it. This is Sam Nunn's stuff as chairman of the Senate Armed Services. They're the ones who confirm. But Sam wouldn't have interfered, and Aspin and Ron Dellums had a special connection, the only two liberals on the House Armed Services Committee. And Ron's an African American.

Vernon said, "These are the people I want you to get letters from." I said, "Vernon, letters?" He said, "Yes. Just do it. I know you think letters don't do any good, but we're at the point now where he's ready to make a decision, so get some letters in." So Howard and some military guys to say the military like me and stuff like that. That was easy enough to do. He said, "But you need to get them in by--" I don't know, the next three days. Why? Because he's about to leave for Martha's Vineyard. He wasn't going to be around the next month to shepherd it. He wanted him to do it.

My meeting with Ron Dellums, the same thing. Ron said, "We're concerned about this thing. We think there needs to be--" "We"? I don't know, the caucus or whatever-- "We think there needs to be a minority in this, an African American. You're the best person." I don't know whether he said there were some others being considered or not. He said, "So we're going to support you." What I'm trying to remember is whether he asked me to do anything. No. Just we had a meeting and that's what he said. He said, "I'm going to write a letter" or something. I guess that would have had an effect to a newly elected President and his wife, both of whom were very sensitive to those kinds of considerations, wanted their administration to be representative of America, dah, dah, dah. So by the time that Vernon was ready to leave for Martha's Vineyard--not in August--the President ended up up there. Maybe not that year, but he certainly ended up later during his administration.

He was able to call me one Friday night, just a few days later and say, "Well, got all the stuff in, and I've talked to the President. I have to tell you, Togo-- " This is an answer to another question--He said, "The President turned to me when I was talking to him about you and said--When this comes back in the papers, I'm probably going to take it out, but it's useful background-- "and said, ‘Now, I know Togo; I've met him; I know him; I know exactly who he is; I met him over at St. John's Church.'" The "Church of the Presidents" is over there on St. John's at Lafayette Square. "Is he a member there? I know he's the senior warden. Is he a member there, or does he work there?" In other words, is the warden actually one of the little porters who cleans up there, or was I actually a member of this all-white, largely Republican church? In fact, it's often been spoken of as either the Republican Party or the Metropolitan Club at prayer. So I thought that was funny. Vernon thought it was hilarious.

So let me for a minute go to the question of when did I meet the President? On Inauguration Day he came and had a prayer service there. Many Presidents do. When he had his second inauguration, other Protestant churches had gotten their oars in the water. He went somewhere else, but he still came and had an early prayer service there also. It's a tradition. I met him then, but that wasn't really the significant time. We had also just brought in a new rector after our old rector of some 30 years had left, and I had been the chairman of that committee and was the senior warden.

He, before George [Herbert] Walker Bush--although George Bush has a family tradition at St. John's--But Clinton also took to coming to the early service. I guess it's the eight o'clock. My cynical view is that's what Presidents do when they want to go play golf: they get church out of the way early. Bill Clinton was not Episcopal, neither is his wife. One is Baptist and I think she's Methodist. Foundry Methodist is her church, so she's a Methodist. But it's close by. Presidents go there. The Secret Service is comfortable with it. They used to walk across Lafayette Park. In fact Bill Clinton walked across it; you won't see that happen anymore, I don't think.

He came one Sunday. I got a call from the rector at about 7:00 in the morning saying only two words, "He's coming." I knew that meant, "The President is coming. Get down there and be part of the little--" So I was there along with--Well, Luis [Leon] couldn't do it; Luis had to get ready for the service. I met the Presidential delegation, showed him to his--There's a pew that we reserve called the President's Pew. It's way down; it's not the pew in the front; it's midway down, on the left side, left of the center aisle. I got him seated and the Secret Service guy assigned, and then I took a seat a few pews back.

Once he was seated, he looked around. He looked back around and sent his guy to get me and say, "The President wants you to sit with him." So I sat with him during the service. We talked afterward on the way. He talked with Luis. That was sort of the first--I saw him on a number of occasions like that afterward, so over time he could truly say, "I know who Togo West is." He couldn't be quite clear whether I was a member there or whether I was just a guy who welcomed him there.

Funny thing about that, Luis Leon, who is still directing, who you see often in the press, the current President's rector, the President had him give the invocation at his second inauguration, President Bush did. Luis also was reasonably close to President Clinton. In fact, he told President Clinton that he was distantly related to him by marriage. And the President acknowledged that; they found they had some common cousin. So, a very bipartisan city even in its most partisan time.

But that's how I ended up there. I had no involvement in the campaign at all. I never offered advice; I never traveled anywhere; I never raised money. In fact, I almost waited too late to contribute to his campaign. Who do I mean by that? Well, Howard Paster at that time was with, I forget which--he had been with--

Martin

Hill & Knowlton?

West

That's where he was then, and before that he'd been at the one that the Republicans out of the Ford administration all established together.

But Howard, specifically, had been one of my consultant when I was at Northrop, so when all of this is going on--Howard is about as knowledgeable about Democratic politics as anybody I knew, so I kept saying, "Howard, is it time for me to send my contribution to the Democratic Party?" He said, "Wait, you have to pick the right event." When I looked up, all the times had passed. As it was, I remember they said, "Oh, it's too late. They've got all their money, and it's going to go to the DNC." So I never even really got credit for contributing to Bill Clinton's first campaign. Long answer to some short questions.

Martin

Absolutely not. I want to go back to this first year of the administration, but I want to ask really quickly. You might have already exhausted it.

West

I may have exhausted you, but I haven't exhausted what I can say.

Chidester

You haven't exhausted me.

Martin

We can go for days.

Chidester

A lot of people have commented about their first meeting with President Clinton and his personality, and the way that he embraces people has become almost legendary. Do you have anything else to add about that first meeting at the church?

West

No, I don't. I have some things to add to the general lore. Here's the thing: later on you'll want to know, well, when I was in the Cabinet and all this, how often did I meet with the President? The fact is, I rarely met with the President, either as Secretary of the Army or as Secretary of Veterans Affairs. But I was places with the President; I did things with the President. Any time the President moved that did something with the Army, I was there to greet him, to welcome him [shows interviewers a picture]. There we are, two fat guys in Haiti. See there, that blue thing right by you? So, he went to Haiti? So did I. I was there before he was so I could greet him and walk him around. See the two fat guys strolling around in Haiti?

He went to Germany to get ready to go into Bosnia. I was there. I don't have a picture of us together, but that's me on the ground waiting for him, or something like that. I forget which. I have some others somewhere that are better than that. He went to Atlanta for the Olympics, and the Army was doing a lot to support it--That picture's at home. Here I am with him going down on Air Force One, and out there is "Flo-Jo" [Florence Griffith Joyner]--God rest her soul--sitting with me in the stands. And you should take a good look at that picture; it's right by the door. Look at the little plaque that says who took it, because the photographer was James Lee Witt, Director of FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency], who was along on every trip and who I think took the picture. And I didn't think about it at the time until I looked at it afterward. Obviously the thing for me to do then was to say, "OK, give me the camera and I'll take you with her." It never occurred to me to say it.

So, no, the first time I ever met the President, we're in church. As we're coming out, I chatted a little bit with him, but he's got other people, and he's got Luis waiting--So, not there and not on the subsequent ones. Whenever I would meet him and take him on these things, I could barely shake his hand and get him going, but I've got to introduce him to all the generals and all the generals' wives. Then he's got to go talk to the servicemen, because if he doesn't, there's going to be rumbling about it the next day. He's got to talk to the NCOs [Noncommissioned Officers]. So never really until I started turning up at White House dinners later. But my impression of him and his interaction with people comes less from his interaction with me and more of my observation of his interaction with the people I introduced him to.

I never took him to a single enlisted, or the wife of an enlisted, or the husband of a deployed enlisted woman, and had the impression that he was listening just long enough to be courteous so he could move on to the next person. I always said of Bill Clinton, he never met a person he didn't want to talk to, that he didn't like to talk to. And more importantly--or worse for that person, in some respects, because they could never break loose--he would like to hear all their ideas. He wanted to hear what they thought. What did they believe? What did they think about this? That's very interesting but what about this?

In my view, it's why his ratings remained consistently high and why he got elected easily and why the Newt Gingrich-led House of Representatives took such a hit there. Right after, in the midterm election, between Monica [Lewinsky]--That's his reelection--they took a big hit because too many people didn't like them going after him because they thought him a person who had genuinely taken an interest in them as individuals. Here's the thing: you can meet anybody. No matter what your notion about him, your preconception about him or her is, if he takes an interest in you--"You know, he must genuinely like talking to me. Maybe he even likes me. I think he does--" it's hard not to like him back. I think that the heart of the Clinton phenomenon is that everybody likes him back. That is, he likes them first, individually, and they like him back. That's my take.

But for me? He never really had a chance to do that until I'd known him a long time and by then--My view about Clinton as President was, it was such a relief. This is not a knock on any previous President; it is just not. Every President that I've ever served, whose term I'd been in in Washington, has had strengths and weaknesses. But it was, in many ways, a relief to me personally to have a President about whom Europeans could not make snotty comments in terms of intellectual capability, grasp of the issues. He may have been a wonk, but he was a genuine wonk. He was a wonk because he was really interested in this stuff. He cared about what the wonkish stuff produced in terms of effects on people.

Chidester

I'm glad I asked that because that was very valuable. I want to go back to a couple of questions in this first year. I don't think we've talked to someone who was in your position, being with the contractors the first year. I think it would be really valuable to get your thoughts on military policy this first year. You have a relationship with Les Aspin, Secretary Aspin--

West

I was really disappointed to see him go. When you think about it, he brought me in. My commission there on the wall is dated November 22nd. That means not long after I am aboard--I have a whole bunch of photos of his welcoming ceremony for me and all that stuff--he announced his resignation. I remember everything leading up to it. I remember all the blame that was parceled out to him in various written commentaries that the reason for Mogadishu was that he had personally refused to respond to the request for additional equipment there. This could have saved the lives of those soldiers. But I felt, by the end of the year, he had essentially turned that corner, that people understood, and that in fact his stock was getting better.

It was a personal disappointment to see him leave, and I wasn't pleased at the sense that the White House either pushed him to leave or didn't sound encouraging enough to keep him when he said he was going to leave. That was in spite of the fact that I knew Bill Perry well. We had served together during the entire four years of the Carter Presidency, and in the last two years we'd served together closely. But what was your question?

Chidester

According to the media at least, which is what the story is out there during the time, the two big perceptions about military policy is, one, you get the big huff about gays in the military, and then you get this other notion that President Clinton is almost ignoring military policy in favor of--especially in economic policy--deficit reduction package and a stimulus package. What was your perception from within the defense community? Was this accurate? Was his administration ignoring this policy for the first year? Were they doing a lot behind the scenes in this area?

West

I think the latter part of the perception is not far off the target. They weren't ignoring it. It's just that, for a President it's never a matter of whether you're ignoring and what you're paying attention to. It's all a matter of priorities.

The constant battle among Cabinet and Sub Cabinet, but especially in the Cabinet in those days--and probably still is--much is made of the shift of power over policy and the like to White House staff and special staff. But it's still a fact that the Cabinet Secretaries are the ones who go to battle over the budget. Frankly, the priorities of a President and the priorities of an administration are always reflected in the budget. That's where the fights get hammered out. That's where Presidential direction is most clearly given. Yes, I know that Presidents and their advisors make compromises here and there, and so pretty soon it's hard to figure out what the priorities are in the budget, but they're there.

The fact is, it's not that the President was ignoring the demands of national security; it's not possible for a President to do that. They seize him by the throat the minute he arrives, and they don't let go until the very last minute. But it is true that his priority was to get the economy in order, and the other priority, which foundered, was health care.

So that part, yes. But there's something else. You know, especially new Presidents, Presidents who step into it for the first time whether they're--I remember when I was growing up--I was in elementary school--we had a discussion at one point--It must have been sixth or seventh grade if it had an impression on me--and my teacher, the nun, Sister Mary Virginia, said, "The best candidates for President, the most successful ones, are Senators, not Governors, because Senators have had a chance to plan all the national issues, and Governors--" and of course now, these days, the common wisdom is just the reverse. The most successful candidates are, and the best candidates may be--Well, the answer to both those is, yes, but it's Vice Presidents who you see the most. They may have gotten, in the old days, the real responsibilities, but they're the ones who probably come into office best equipped to be President, if they get to make that step, because there's just nothing like what you get to face in the White House. Most Governors and Senators do not show up understanding the point that we just made, which is national security--the relations among nations, whether diplomatic issues or the raw power base, if its military issues--will grab a President no matter what. So he wasn't able to do that.

But his first year was hijacked. His first military year was hijacked because of gays in the military. I mean, for reasons that were not clear to me--I wasn't there; I didn't arrive until November--but suddenly he finds himself, I think, in response to--They learned this later, responding to a reporter's question or what have you--that the big issue that drives everybody is, "Oh well, you said you thought that the service should be open for gays to serve in the military. Well, here you are. What are you going to do about it?" "Well, I'm going to see it through." "Oh, OK." This is a big issue.

So, suddenly the perception is--and sometimes the perception really can surpass reality--The perception is that Bill Clinton is focused on social issues in the military, not the tough issues: North Korea and the Middle East, which, by the end of his eight years, were a big part of his focus. I mean, there was his visit--the first President to visit Vietnam. His abortive--and he came close--visit to Korea, all sorts of things. A real effort to hammer out a North Korea strategy that was pretty much dashed the minute a new administration came in. So big change there from beginning to end, it would seem. But in fact I think the attention had to be pretty serious all along. But the first six months to a year got hijacked over an issue that never should have been so much of a front-burner, high-octane, high-profile issue.

The military and its lawyers--and I would say that having been one--have always known that the United States of America had to deal with the issue of the service of gay Americans in the military, just as they have always known how to deal with the issue of the service of women in combat and combat-related assignments, which I know you're going to get to. It is not a complicated issue. It may be delicate, but not complicated. The outlines of the solutions and how you should deal with them are very clear.

But once you start hashing these things out in the--I was about to say "overheated." I don't know if it's overheated, but just the heated atmosphere of public statements and press stories and then people saying, "Oh, my God, the foxhole. What's going to happen in the foxhole?" Well, nobody's been in a foxhole in decades, so it just got hijacked. So the perception of the first year, his attentiveness to national security matters, is probably somewhat off center. But the notion that his priorities may have been first and second among some other things is probably correct.

There's one other point I wanted to make about that. Remember, he was an inexperienced President and an unsure President in terms of dealing with the military. So he was also--and this, I think, has been said, and it's true--very tentative in the way he approached some of these things until he got a sense of how officers were going to deal with him.

Now, nice things happen for Presidents if they get the right kind of advice. There is always a change in the chairmanship of the Joint Chiefs of Staff within months after a new President--well, within months after a new administration, not just a new President, a new administration. The President is sworn in on the 20th of January. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs leaves at the end of September of a new administration, always, just because that's the way the two-year statutory terms are set up. And it has rarely been the case that a Chairman has been reappointed more than two years. There's actually a prohibition against it, two back-to-back terms. That means four years. So every time there's a new administration, you can count on it.

Colin Powell was leaving at the end of September anyway. But he was there for the first six months. Colin was a good guy to have there. Colin is going to try to help a new President get a feel for things--and he did. But he's still not your guy; you didn't put him there. In fact, he's a guy who has, or soon will, turn down your offer to be in your administration. So if you get a chance to meet folks, you do get to put your own person in. By "own person," I mean someone whom you've gotten--You know Presidents can get to know their senior leaders.

In those days--and I bet they still do something like it--all the so-called CINCs [commanders in chief of the branches] around the world, the four-stars who command major regional commands--They're not CINCs anymore because Rummy [Donald Rumsfeld] decided he didn't want to be that--but the major commanders come to Washington for meetings with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Secretary of Defense. There's always a dinner at the White House. They invite the service Secretaries, or at least they used to. They meet with the President, and they eat with him.

And as hot spots develop, he ends up talking to them--It's not possible not to. Yes, a lot is filtered through the SecDef [Secretary of Defense] and the Chairman, but he gets to know them. So over time a President gets more and more comfortable with them. But the first six months to the first year, he's not that comfortable if he's not been there before. Bill Clinton had not been there before in any form.

Chidester

When you first agreed to be Secretary of the Army, do you get any conveyance from Bill Clinton or the White House what they expect you to do, what your charge is to be Secretary?

West

No, what you get is a sort of funny--Everything leading up to your swearing-in is consumed by the complicated dance of conflicts of interest, disclosures of anything possible in your background, vetting, meeting people who interview you. And if you ever get through the phase that leads to a determination that they may want to go forward with you--and the process has changed. When I was vetted and nominated to be the general counsel of the Department of Defense, the President's decision eventually was conveyed by sending a notice over to the Senate. Now they send over a notice of intent to nominate, which is before they send over the nomination. Apparently this serves to sort of--It's the starting gun. "OK, everybody on the Hill now who has anything to say about it can say stuff about it." Well, you go through that process. You spend all your time getting through the process, none of your time talking about what you're going to do when you get there.

Now, I had some back-and-forth with Rudy de Leon in Les Aspin's office. He had some problems. I remember he once commented to me, "Boy, I know exactly what I'm sending you the first day you get here. I've got something on my desk for the Secretary of Defense that we're going to get off and put on the Secretary of the Army's desk." Fine, but no one calls you in and says, "These are the things you do as Secretary of the Army." Presumably, if you're going to do the job, you find that out yourself or you already know it. I mean, I knew what I was going to do. I knew the duties of the Secretary. I'd read every single thing there was about it. That's what lawyers do. I had been the general counsel to DoD. I spent a lot of time telling the Secretaries what they were supposed to do and fighting with their general counsel.

The Secretary of the Navy, I fought with the general counsel of the Navy. Navy general counsels always do that. You notice they were fighting recently between Alberto Mora, the general counsel of the Navy and Bill Haynes, who was nominated for court over the rules governing the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay and a whole bunch of other things. So I knew what the duties were. I knew what the responsibilities were and what the authorities were.

As I was going through the process, I tended to think of the Secretary of the Army as like an ambassador. The thing to remember is that even ambassadors have things they have to do over there. But for the service Secretaries, they have extraordinary powers. Now they get a lot of help in how to use it and a lot of advice, and everybody that works in OSD [Office of the Secretary of Defense] or in the White House thinks they know what to tell the Secretaries they should do. But the only person in Washington in the Department of the Army that has command authority is the Secretary of the Army. Chief of staff has no command authority, nor do any of those generals who work in the Pentagon. They don't have command authority.

The only person in OSD who has command authority is the Secretary of Defense and his deputy. The various Under Secretaries get to boss their own officers around. They can issue memoranda setting out policy, but the command, for example, of our forces in any part of the world runs from the--Well, the President, the Secretary of Defense, and the Deputy Secretary of Defense form something known as the NCA, the National Command Authority. The line of authority, the ability to command troops to move, planes to fly, ships to sail, goes directly from that triangle to the regional commander who controls the forces at issue. It used to be CINCUCOM, the Commander in Chief of UCOM [Unified Command], the commander of U.S. forces in Europe, which is one of the hats of the SACEUR, Supreme Allied Command in Europe. He has two hats: he's the NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] guy, but he also plans U.S. forces in Europe. Most of his work is done by his deputy in Stuttgart. That's where the actual--But that's a direct command line.

The only role of the Joint Chiefs is that they are, through the Chairman, advisors, and they're also the mailroom. That is, they actually transmit the order. You know it comes from the Secretary or the President because it is coming from the Chairman, who says, "This is what the Secretary ordered." Well, by the same token, only the Secretary of the Army issues instructions to various forts and the like and divisions who are here. The chief of staff issues them by order of the Secretary. All that is probably more detail than you want. But also in those days there were lots of other hats.

Historically it is the Army that has been the link between the military and the people of the United States. When there is going to be martial law--We don't have it anymore; we never use it; we'll never invoke it; it's still on the books--it is the Secretary of the Army who is the martial law administrator. Now, that can change over time.

Anyway, there are a lot of roles that come from that. That meant that in the emergencies that require FEMA, which always needs military support--principally the big planes to transport stuff, but also we use those big planes to help the fire people dump chemicals on forest fires--we use both planes and Army transport to get stuff like sand and salt to places where there are blizzards in the winter. If it's the Northridge earthquake out in California, James Lee was out there because FEMA comes in. But he gets most of his support from the Department of Defense, so I'm there because I'm the lead person, and I have the authority--the Secretary has the authority--to issue orders, to execute orders, which is the big deal in the department because normally that's only the Secretary can issue, execute orders to any of the services to provide assistance in those circumstances.

Now, there has been a long-running battle over that. Colin Powell really didn't like it, and he got Bill Perry's ear in the six months that--No, Colin was gone, so it was Les--no, Bill was the Deputy Secretary. I'd always get inquiries from Bill Perry saying, "Should we switch this over? Should maybe the Joint Chiefs have more of a role in this?" I had heard that during Rummy's time they've actually moved all that authority up and taken it out of the AOC [Area of Command]. We used to have a Major General, Director of Military Support, called DOMS. It's changed, but then it hadn't.

The Secretary still has a lot of those roles, though. He is the chief domestic-support person for the U.S. military, still, and the Secretary's advisor. All the base closings, all the budget stuff, it's all the Secretary's. The Secretary is the person who forwards promotions to either the Secretary of Defense for the Hill, or on some of those have to go to the White House. So when the question is who is going to be the next four-star commander of an Army operation somewhere, or three-star, then that's more the Secretary's and the chief of staff's call. If it is one of the joint, or unified, commands where everybody sends up a name, then that's more the SecDef's call. Then all of them have to go to the President for approval before they go over.

So the Secretary plays a big role in those things. The many roles of the Secretary--but the biggest ones are in the tussle within the establishment over things like budget, and that process goes on all the time. In the Pentagon and all the agencies, there are at least three budgets that you're fighting over: the one that is about to end, where you're still trying to squeeze some more out of it or get some additional authorities; there is the one that is about to start, which has already been through the approval process; and the new one that you're ginning up to start the process again.

It's all about what we discussed earlier. It's all about the real question as to where the President's heart ought to be. Is it with this way of structuring the Army around these kinds--? When you make decisions of the sort they talk about--leaner, meaner, or a different structure--you go from the triad, get rid of divisions, just add brigade task forces and the like, brigade combat teams--you're also making hugely expensive decisions about the hardware that goes with it. So that's all civilian decision making, heavily influenced--maybe even overwhelmingly influenced--by the experience of the generals you've got to work with.

And while you're doing that, you're balancing that kind of stuff against the fact that all the services are made up of people; that people have to have somewhere to live; they have to have bases; they have to have fair pay; there's retirement; there's health care for them. And those are all at war in the same budgets. So you also are tugging at the President's heart over, "OK, are we going to take care of our people? Is it so important for us to have this force be able to do this thing because of what we're seeing over here?" Then, when you're deployed--And we've always been deployed in the last several decades. We're more than deployed now: we're fighting a war. When you're fighting a war, that's just doubly difficult, because the war tends to drain everything. There's always a draining from accounts that were originally funded in the budget to do one thing, in order to take care of the exigencies where the theater is. All of that is the service Secretary.

Whenever the showdown occurs, whenever the slinging of the guns at the OK Corral occurs, it is the Secretary who's got to march up and sit down in front of the Secretary of Defense and fight it out. By the persistence, by the polite--courteous, admittedly, but nonetheless strong--sometimes maybe vociferous presentation by the Secretary and chief of staff, those two, the Secretary of Defense either gets a sense that this is important to the service or it's not; it's more important than this or that.