The Presidency in Crisis

Even before the Watergate scandal came to light, scholars and journalists started to debate what had gone wrong with the American presidency. George Reedy, former aide to Lyndon Johnson, critiqued the unchecked power the chief executive wielded in his 1970 book, The Twilight of the Presidency.1 Arthur Schlesinger Jr., a prominent historian and former advisor to John F. Kennedy, classified this state in which the institutional authority of the office had exceeded its constitutional authority as the “imperial presidency” in his famous 1973 book by the same name.1 That same year, journalist David Wise lamented the web of lies presidents had constructed to mislead and deceive the American people in his The Politics of Lying: Government Deception, Secrecy, and Power.3 Even before the details of the Watergate break-in and the litany of presidential abuses in the Nixon administration came to the surface, it was clear to many that the shift of concentrated power in the chief executive threatened democracy. These works were “forerunners to the theory that the cause of Watergate was the accretion of power to the presidency,” contends political scientist Ruth Morgan.4

Scholars agree that the Watergate scandal marked a transformative moment in American politics and culture. As the historian Keith W. Olson contends, “Watergate and Vietnam…contributed significantly to a fundamental distrust of government that has continued into the second decade of the twenty-first century.”5 President Lyndon Johnson’s controversial and problematic engagement in the Vietnam War both expanded the institutional power of the office and distanced the president from the people.

These cracks in public trust of the presidency were widened during the Nixon administration. When The Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein drew attention to a June break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in 1972, they began an investigation into illegal activities waged by members of Nixon’s reelection committee. The following February, the Senate launched a congressional investigation into the alleged misconduct of the burglars, and as the narrative unfolded over the next year, it became clear that the fears of criminal activities, wire-tapping, and abuses of power were validated—and even worse than many suspected.

The televised Senate hearings in the summer of 1973 brought the crimes of the Nixon White House—a break-in at the Watergate hotel, subsequent cover-up attempts and bribery, and a range of dirty tricks the president used to target his opponents and punish his enemies to gain personal power—directly to the American people. The Watergate investigation, which played out in Congress, the courts, and the press over the next year, confirmed public suspicions of presidential abuses of power, and as a result, fundamentally altered the relationship of the presidency to the people, the press, and Congress.

Historians have paid significant attention to the crisis of the American presidency that unfolded during the 1960s and 1970s. While some have focused on the power-hungry and paranoid personality of Richard Nixon, others have seen Nixon not simply as an aberration but also a product of shifting political and cultural values in the post-WWII period and the expansion of the presidency as an institution begun over the course of the twentieth century (a historical development this website examines).6 This section examines these historical arguments, situating the Watergate scandal as a culmination of the personal, political, and institutional changes of the executive branch over the previous decade. This module offers students an opportunity to think about historiography along with understanding the multifaceted roots of the crisis of the American presidency during the 1960s and 1970s.

The Credibility Gap: Watergate as the “Last Chapter of the Vietnam War”

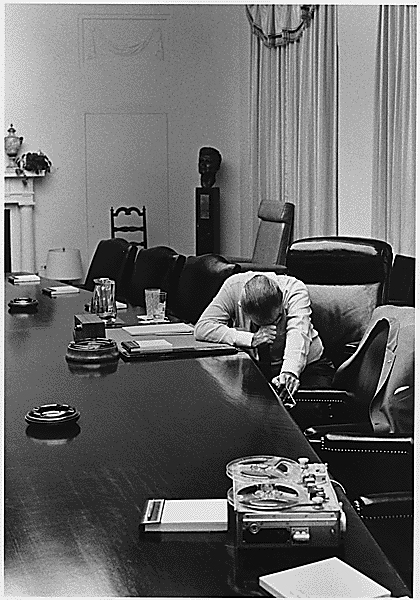

President Lyndon B. Johnson listens to tape sent by Captain Charles Robb from Vietnam. Source: NARA. [view larger]

Since Franklin Roosevelt’s administration, presidents have increasingly intervened in southeastern Asia. Following WWII, Harry Truman supported colonial France against Vietnamese nationalists mobilized under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, whom Truman and Eisenhower both viewed as ‘Moscow-directed.”7 When France was defeated in 1954, Minh accepted a temporary agreement to divide the country into a North and South Vietnam, believing that national elections would soon eliminate this partition. Viewed as part of the Cold War, in which the United States used military and economic resources to contain the spread of communist influence from the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union, Eisenhower and Kennedy saw reunification under Minh as a Cold War defeat. Before his assassination, Kennedy publicly called South Vietnam the “cornerstone of the Free World.”

While Johnson used Kennedy’s death to push through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he also found himself bound by Kennedy’s promise to maintain support for South Vietnam. And, by all accounts, the new president was “out of his element in foreign relations,” and as such, relied on insights from advisors, with historian Bruce Schulman noting that Johnson began to “navigate by abstract principles rather than the sure instincts about what really worked that guided him so well in the Congress.”8

Blinded by the ideological lens of the Cold War, Lyndon Johnson slowly, reluctantly, and controversially expanded American involvement in South Vietnam. The international conflict turned LBJ into a villain in the White House, and created a “credibility gap” between the American people and their president.

When Richard Nixon assumed the presidency, he too faced the dilemma of how to withdraw troops from a controversial war while still maintaining the victory that was deemed essential to his reelection in 1972.9 Richard Nixon called himself the “last casualty in Vietnam”—the final chapter of the growing distrust of the president and the increasingly hostile relationship between the White House and the press. This section allows students to examine the institutional growth of the national security state and the implications that Johnson’s escalation in Vietnam had for his successor.

SECONDARY SOURCE

- Bruce Schulman, “’That Bitch of a War’: LBJ and Vietnam,” in Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism, 2nd ed. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin, 2006), 133-178.

PRIMARY SOURCES

The Kennedy and Eisenhower Legacy:

- John F. Kennedy’s last interview on the situation in Vietnam with NBC news anchors Chet Huntley and David Brinkley, September 9, 1963.

- Lyndon Johnson asks former President Eisenhower for advice on the Vietnam War, August 18, 1965.

Public Promises, Private Doubts:

- Lyndon Johnson discusses Vietnam privately during a telephone conversation with Senator Richard Russell on May 27, 1964.

- Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (1964).

- Lyndon Johnson, “Speech to the American Bar Association,” concerning the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, August 1964.

- Lyndon Johnson, “Pattern for Peace in Southeast Asia,” address delivered on April 7, 1965 at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

- President Lyndon Johnson press conference on Vietnam, July 28, 1965.

“Hey, Hey LBJ, how many boys did you kill today?”: Criticism of Lyndon Johnson and Vietnam:

- “Lyndon Johnson Told the Nation” (1965) song by Tom Paxton.

- Paul Potter, president of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), condemned Lyndon Johnson’s actions in escalating the Vietnam War during an antiwar rally in Washington D.C. on April 17, 1965.

Discussion Questions:

How did the Cold War commitment of Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy influence Lyndon Johnson’s decisions about Vietnam? How does Vietnam fit into the Cold War consensus and view of foreign policy that came out of WWII?

What concerns does Lyndon Johnson express about Vietnam behind closed doors?

How does Johnson sell the war to the American people? What is the difference between his private views of the war and his public statements?

Why does Vietnam become known as “Johnson’s War”? Why do protesters focus their criticism on Johnson as an individual?

What does the term “credibility gap” mean? What pressures does it place upon Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon?

GROUP ACTIVITY: WATERGATE AND THE BATTLE OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS

Critics of the Vietnam War argued that the unfettered use of executive authority to wage war and deceive the American people on the progress of that war exposed pressing problems in expanding the institutional authority of the Executive Branch. And yet, the Watergate scandal, though perhaps a culmination of what historian Joan Hoff terms the “decline in political ethics and practices during the Cold War,” did test the system of checks and balances designed by the Constitution to prevent abuses of power.10 In fact, the investigation began and continued because of actions taken by the press, Congress, the courts, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation—all government institutions which pushed back against the growing power of the presidency. As such, Watergate involved a battle between the president and each of these government institutions, leaving each of them fundamentally transformed in the wake of Richard Nixon’s resignation.

Break students into five groups and assign each group the task of analyzing the battle waged between President Nixon and that particular institution. Each group has a particular secondary source they should first consult to help direct their research agenda. After considering the following questions, have each group make an argument about the impact of their government institution in exposing the Watergate scandal and reforming the presidency.

General Reading:

GROUP ASSIGNMENTS

Group 1: Congress

Reading Assignment: Bruce J. Schulman, “Restraining the Imperial Presidency: Congress and Watergate,” in The American Congress: The Building of Democracy, ed. Julian Zelizer. (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004), 638–649.

Group 2: The Courts

Reading Assignment: Anthony J. Gaughan, “Watergate, Judge Sirica, and the Rule of Law,” McGeorge Law Review, Spring 2011, Vol. 42 (3), 343–395.

Group 3: The Press

Reading Assignment: Michael Schudson, “Watergate and the Press,” in The Power of News. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995), 142–165.

Group 4: The Federal Bureau of Investigation

Reading Assignment: Beverly Gage, “Deep Throat, Watergate, and the Bureaucratic Politics of the FBI,” Journal of Policy History, Vol. 24, Number 2, 2012, 157–183.

Discussion Questions:

- How did the presidency, as an institution, become so powerful? How did other government institutions respond to the growth of the presidency?

- Did these changing attitudes in the media, parties, Congress, and courts combat the institutional power of the executive, or did it just amass evidence to show Nixon’s misconduct?

- While many argued that Watergate exposed the corruption of the political system, others pointed out that it demonstrated how the system of checks and balances worked. What is the legacy of Watergate for your particular institution?

RESEARCH ACTIVITY: NIXON AND THE TAPES

Presidents Kennedy and Johnson expanded the White House recording system, and, as the civil rights module illuminates, these recordings provide valuable insights into their styles of governance. But, the Watergate investigation sparked a legal debate between the president and the courts about the content of the tapes: were they Nixon’s personal property, or were they public records that would be preserved by professional archivists at the National Archive and Records Administration, as established by Congress in 1934?11 In Richard Nixon v. United States of America, the Supreme Court mandated the release of the tapes. Knowing the tapes had proof of his involvement, Nixon resigned from office soon after the decision. After nearly four decades of litigious debates about the processing and preserving of the tapes, the tapes have finally been released to the public, providing insight into Nixon’s personality, style of governance, paranoias, hopes, and fears.

Have students listen to a recording in the “Watergate Collection,” and offer an analysis of how each discussion adds to our understanding of Watergate in its entirety. As students listen to their assigned tape, have them consider the following questions and prepare a presentation to the class on their selected recording.

- Who is participating in the discussion and what are they discussing? How would you summarize the content of the discussion?

- What do you learn about Nixon and his presidency from listening to it?

- Why is it included in the “Watergate Collection,” and what do you learn about the Watergate scandal from this tape?

- Historian Stanley Kutler argues that “the wars of Watergate are rooted in the lifelong political personality of Richard Nixon.”12Based on an analysis of your assigned recording, how much of Watergate was a result of Nixon’s individual personality, and how much of the scandal stemmed from the institutional growth of the office of the presidency?

Footnotes

- ↑ George E. Reedy, The Twilight of the Presidency, (New York: The World Publishing Company, 1970).

- ↑ Arthur M Schlesinger Jr., The Imperial Presidency, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973).

- ↑ David Wise, The Politics of Lying: Government Deception, Secrecy, and Power. (New York: Random House, 1973).

- ↑ Ruth P. Morgan, “Nixon, Watergate, and the Study of the Presidency,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 1, (Winter 1996), 218.

- ↑ Keith W. Olson, “Watergate,” in A Companion to Richard M. Nixon, First Edition. Ed. Melvin Small. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2011), 497.

- ↑ For an overview of this historiography, see Morgan, “Nixon, Watergate, and the Study of the Presidency” and Olson, “Watergate.”

- ↑ A concise overview of the origins of the Vietnam War and Lyndon Johnson’s decision to commit troops and resources to uphold Kennedy’s promise can be found in Bruce Schulman’s Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism, 2nd ed. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006), 133–165.

- ↑ Schulman, 133–134.

- ↑ Ken Hughes, Fatal Politics: The Nixon Tapes, the Vietnam War, and the Casualties of Reelection, (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2015).

- ↑ Joan Hoff, Nixon Reconsidered, (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 341.

- ↑ For the history of the National Archives and Records Administration see: http://www.archives.gov/about/history/.

- ↑ Stanley Kutler, Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon, (New York: Knopf, 1990),617.