Smaller but sharper

Imagine a new president who sets a tone of governance among a team of top-flight senior managers who are determined to restore the confidence and trust that Americans once had in their great public institutions.

Imagine that this president is working to build key alliances in the Congress well before Inauguration Day.

Imagine a president doing all this with a radically smaller White House staff that actually increases the president’s own influence, simultaneously empowering departments and agencies yet holding them more accountable.

Imagine a president focused on policy execution with policy development incorporating and linked to the budget process.

Imagine all those things and you would be imagining a changed American government. Yet none of these goals is unattainable. All have been achieved before and can be again, adapted to 21st-century needs.

1. Prepare to govern

When running for office, politicians master the art of judging what stands to take on positions and how best to represent these choices to key audiences. None of that stops when a candidate becomes a president.

It is worth reflecting consciously about just how the core skills of governance are different from the core skills of electoral politics.

To govern is to

- define concrete, operational definitions of success;

- work through alternative strategies of how to attain those objects;

- design the many actions needed to make such strategies real and assemble the requisite coalitions;

- follow through; and

- make constant reviews and adjustments as plans encounter reality.

In campaigns, the speech is often the end point. In governance, the speech is usually just the starting point.

True, some of the skills of governance overlap in the electoral campaign worlds of field organization, scheduling, or media buys. In campaigns, the speech is often the end point. In governance, the speech is usually just the starting point. And the power to get anything done is always shared among various people and institutions.

All successful presidents have a shakedown period in which they figure out how to compose and lead a team that is good at governance. The winning campaign staff is wary of anyone who tries to profit from “their” victory without having fought the election battle. As presidential historian Dick Neustadt once observed, “A golden haze of brotherhood descends at the moment of election on the campaigners and on their winning candidate, but on no one else.”

People who are good at high-level governance are both choreographers and orchestra conductors. They have a zoom lens that can range quickly from the macro view of a landscape to the precise focus on a given detail within it. They have a mastery not only of the general subject theme but also of the characteristics of various channels for taking actions.

One reason why FDR, Eisenhower, and George H.W. Bush were all reasonably successful at governance was simple: they all had substantial prior experience at it.

No one person possesses all the ideal talents for governance. A president can compose a team or, more accurately, a team of teams, to blend the needed strengths. The president’s attitude toward governance will set the tone.

2. Build policy partnerships in the Congress, even before the inauguration

Practically all briefing papers for new presidents concentrate on the White House and the executive branch. Congress is treated as an object, a fortress to be assaulted.

The Congress is rarely considered as a base for presidential launch planning. But if the president can identify key allies (and she or he must), then those parts of the Congress can become a vital base for work.

In Congress there are usually committee (and some personal) staffs that have been cultivating issue expertise on a given subject for years. They often have draft legislation filed away. Some early and carefully selected partnerships can provide a basis for much quiet planning.

In 1989, as President Bush took office, the largest open wounds in relations with Congress were constant battles—more than a decade old—over U.S. policies in Central America. Those battles, as they erupted in the Iran-Contra scandal of 1986-87, had nearly brought down the Reagan administration.

Even before Bush took office, secretary of state designate James Baker and his team made a major effort to build understandings with the Congress that would defuse this contentious issue and allow them to focus on other priorities. The effort extended to the nomination of a centrist Democrat (Bernard Aronson) as the State Department’s assistant secretary for Latin America.

The effort was successful. After more than a decade as a fault line in American politics, Central America became a little-noticed area of regular bipartisan cooperation (and policy success).

By contrast, in 2008-09, when President Barack Obama set out to close the Guantanamo Bay detention camp with an executive order at the outset of his administration, his aides did share a draft of the order with a few people in Congress to get some advice on it. But they never worked with congressional leaders who might then have become allies—like Obama’s just-defeated opponent, John McCain—in order to find an approach that might have worked.

For instance, the executive order failed to think through and specify where the transferred prisoners would end up. Therefore, instead of being opposed by the congressional delegation of just one unlucky state, Obama’s executive order was opposed by representatives from one end of the country to the other, all of whom quickly issued NIMBY statements to reassure their constituents. The politics of the issue soon became poisonous for the administration.

The point is that no major policy issues can be tackled solely by executive branch initiative, although that initiative will be essential. None of these issues are likely to be meaningfully addressed in an administration’s first year if work on them is deferred until January 20.

All the possible solutions will require months of advance staff work and policy development. That work is much more likely to be done in congressional offices than in campaign-managed transition processes. So early partnerships with congressional allies can be a key base for transition planning.

Another key reason for congressional partnership is to gain aid with updating and managing the critical institutions. Most advice for new presidents assumes that the government machine works; the advisors just argue about how to steer it. Wrong.

Significant portions of the U.S. government are now so beset by out-of-date institutional designs and badly maintained as to be profoundly dysfunctional, to the point where they cannot be relied upon to perform presumptive tasks. It may not matter where the new president wants to steer the car if the tires are running flat and the engine is coughing in and out of life.

Moreover, the next president will take over a U.S. government that is involved in secret operations around the world, more than perhaps at any other time in history. The details of these operations are highly classified and compartmentalized, protecting against leaks but also blocking the usual checks and balances of peer review.

3. Treat good policy development—written staff work—as a matter of life and death

Because it frequently is a matter of life and death. This point is usually well understood among those engaged in dangerous field operations. It is not as clear to their top bosses, the ones who authorize and guide such operations.

Top officials and their staffs often know a lot about general subjects. They may be canny in their grasp of bureaucratic processes. But, in general, they are not trained in how to do policy analysis or related staff work to explain their analysis, crisply articulate key assumptions, or delineate the choice of operational objectives, and the rest.

Instead, the bureaucracy is slowed by an interagency process that consumes more and more time in less and less consequential meetings. The meetings become something the better officials wish to avoid.

The White House then adds more staff to watch over what the executive agencies do, a kind of American version of the old Soviet commissar school of management: announce the party line, monitor the functionaries carefully as they interpret their “guidance,” and shoot a few to encourage the others.

The result may strengthen the White House staff, yet that does not actually strengthen the president (the two are not synonymous). It certainly does not encourage quality staff work from senior managers. Instead, it reduces them and their teams to being, well, functionaries.

Americans once knew how to translate ideas concisely into operational alternatives.

Building on their own vast experiences with government administration during the New Deal and World War II years, Americans once knew how to translate ideas concisely into operational alternatives. Arguments and choices were carefully noted and clearly communicated to those who needed to know. Relevant factual assumptions—about foreigners or our own side—were rigorously tracked.

The American policy professionals of the 1940s and 1950s managed colossal efforts at this level of professionalism with staffs that are tiny by today’s standards (and with no computers or e-mail either). To anyone who reads the historical records from these years, the quality of the paperwork is often strikingly good, identifying issues and clarifying arguments.

Top officials, from the president on down, were quite accustomed to reading, critiquing, and sometimes composing detailed policy papers. Senior managers grew used to interacting at this level of constant peer review, which in turn raised the level of the game within their agencies. Those who could not keep up were soon replaced.

Yet little of this was formally taught in U.S. schools. These good habits slowly disappeared and were forgotten. In recent decades, the level of substantive policy staff work across much of the U.S. government cannot be favorably compared to the paperwork routinely found in the archives even as late as the 1960s and 1970s.

Back when he was the deputy national security advisor (1989-1991), Robert Gates was known for his skills in staff work and analysis. He insisted on policy work so good that decisions could be made and executed entirely based on the paperwork. Often the differences in agency views were so clearly and fairly stated that no meeting was needed in order to get the required White House decision. If a meeting was necessary, it was better prepared and sharply focused.

An oft-given reason for not doing good written work is the horror of leaks. This worry has diminished a little in recent years but it is still serious. This is a risk that must be courted. The FDR war years, for example, experienced some leaks that were extremely serious. But at no time did the president or his key advisors abandon the staff work habits that they regarded as vital to guiding the work of a vast government.

An insistence on quality work must start from the top, with the president. No national security advisor can enforce quality and timeliness controls if the president does not back her or him up, and with some heat. If the president is content to ruminate, or will sit still for unilluminating PowerPoint bombardments, or won’t pay attention to written details, those examples will set the tone for the rest of the team.

4. Link policy making to budgeting

The present White House, like most of its recent predecessors, is at its best when making policy in words in a speech or on a page. Yet the process for guiding and coordinating policy implementation has substantially broken down. This is not a partisan point. At one point in the administration of George W. Bush, national security advisor Steve Hadley graded his own administration’s efforts at policy implementation at about a D-minus.

Viewed historically, the last time the NSC seems to have handled these program coordination problems reasonably well was in the Eisenhower administration. Eisenhower then had an Operations Coordination Board to perform just this function, allocating resources as Ike cut back defense spending requests and prepared the government to wage a long Cold War. Eisenhower’s NSC also had a very innovatively designed Planning Board on the other end.

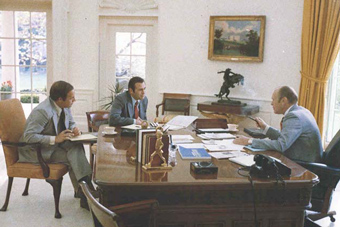

In the Eisenhower system, the NSC sat atop what officials then half-jokingly called “Policy Hill.” Policy papers traveled through the interagency committees, shepherded by the Planning Board, to the top of the Hill. They were considered in the Council with Eisenhower very actively chairing, and then were escorted down the other side of the Hill, through the Operations Board’s committees, to the departments and agencies.

Thanks to Ike’s intense personal commitment and the skill of his first national security advisor, the too-little-known Robert Cutler, this system worked, especially in the early years. But Eisenhower’s approach is not the only option. FDR’s approach, which was quite different, also often worked well. But all of this institutional memory was lost in following decades.

To improve the situation, a mix of options can be considered—including reviving an Eisenhower-style system or having a deputy national security advisor who concentrates on policy implementation. Another ingredient, however, should be to rebuild the link between policymaking and budgeting.

Leading OMB officials and their budget reviews should become core participants in the national security policymaking process, as they once were.

The NSC rarely does any budget work, this being left to the separate OMB-led process. In fact, partly because of the way information is distributed in the government, the NSC staff rarely has much insight either into the budgets or the operations of any agency except for the State Department.

Leading OMB officials and their budget reviews should become core participants in the national security policymaking process, as they once were. As any manager of a large enterprise knows: manage the money and you manage what is done.

An undoubted priority of any new president in 2017 will be the weight and allocation of defense resources. How could a different process work in that sphere?

The president could consider, well before taking office, the redesign of the current Joint Requirements Council that weighs competing service and agency requests within the Department of Defense. A new joint requirements board might add other civilian votes to the process, weakening logrolling among the services. If an NSC staff member sat on such a board, providing national input and representing the views of OMB as well as the NSC, both sides would have more insight into resource allocation judgments and the embedded priorities they represent. Analogous suggestions could be considered for the intelligence community budgeting process overseen by the director of national intelligence.

This approach could be part of a management strategy that relies on more accountability with fewer staff positions. The current administration constantly engages NSC staff down in the weeds, dispersing its influence.

Better results would come from a much smaller staff, with fewer and more influential senior members. They should concentrate less on matters that agencies can do for them and more on the higher-level planning, requirements, and budget decisions that should properly engage a president’s interest.