Agrarian protest in the 19th century

Following the Civil War, farmers launched an attack on America's two-party system

Excerpted from What Happened to the Vital Center? by Sidney Milkis and Nicholas Jacobs (Oxford, 2022)

During the tumultuous post-Civil War era a massive populist protest engulfed the country. In what was clearly the largest and most widespread populist movement to date, thousands of farmers across the Midwest and South launched a decades long attack on the political establishment and the two-party system that nourished it. Infused with a sense of indignant furor against Eastern banks, local merchants, and a corrupt political class, American agrarians organized themselves in order to take advantage of the country's growing economic prosperity, which had left their communities behind. Like the Anti-Masons before them, the Populist movement helped to usher in a dramatic remaking of the party-system, paving the way for additional reforms during the Progressive era and New Deal. Yet they were unsuccessful in enacting their most ambitious plans for economic and political equality. In response to populist unrest, both Democrats and Republicans alike used the built-in advantages of the late 19th century party system to largely stifle the agrarian movement. Any gains made by the Populists—in constructing an accessible financial system, in regulating railroads, or in democratizing politics—came later, if at all.

American agrarians organized themselves in order to take advantage of the country's growing economic prosperity, which had left their communities behind.

Drawing on the language of the common man, these "plain people" of the American heartland tapped into America’s egalitarian spirit, which had animated the Anti-Masons a generation earlier. That same sprit would soon embolden other populist movements at the turn of the 20th century, including organized labor and a nascent civil rights movement. Yet, none were as noticeable, organized, or potentially disruptive as were the Populists. In many areas of the country, they represented the clear majority of the population, and their grievances—at the time, and in retrospect—were legitimate. The party system's negligence was a consequence of its structure; empowered local and state bosses had, as reformers argued, rigged political and governmental processes in their favor. So decentralized was the system of mass politics that the Populists struggled to make inroads into the political establishment or to launch a successful third-party insurgency, even when they had majority support in parts of the country. Election after election, in state after state, the Populists faltered.

The Populist movement sought to demolish, not remake, the two-party stem.

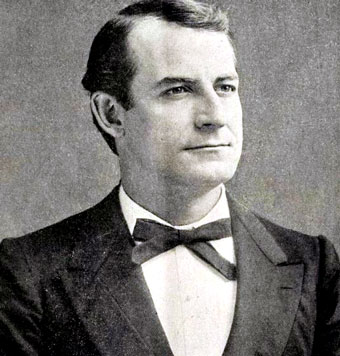

Many students of American history credit the Populist movement as a successful revolt, but these accounts often overlook the anti-partyism that infused the Populist crusade. Nevertheless, such favorable accounts of the agrarian revolt make two analytical mistakes in understanding Populism and partisanship: first, they often neglect how the Populist movement sought to demolish, not remake, the two-party system. While it is true that, in 1896, the Democrats nominated a self-styled populist William Jennings Bryan as the presidential nominee. Armed with a proposal to inflate the money supply—the free coinage of silver—and cloaked in the same evangelical righteousness that galvanized the farmer’s protest, Bryan's nomination might be seen as evidence of the decentralized party system's flexibility to take on new ideas and construct new coalitions. Yet, Bryan’s nomination offers a low-bar for evaluating the movement’s success. He represented a co-optation of Populist idealism—a co-optation Populist leaders had long warned against, which is why they sought to dismantle party organization, not join it. Similarly, Bryan's loss in 1896, followed by defeats in 1900 and 1904, is often viewed as a testament to democratic politics, and his inability to persuade a majority of voters that substantial reform was needed. However, such accounts of the era often gloss over the illegitimate political obstacles —ballot rigging, spoils, extortion, Jim Crow—that allowed the decentralized party system to prevail even as it remained unresponsive to popular protest. The fully decentralized party system, in which nomination and governance decisions were characterized by minimal national leadership and competition, provided no incentive or organizational capacity that might have led party leaders to respond to a national movement.

The Populists recognized this extraordinary degree of party insularity, and the movement distanced itself from organized national politics from the start. The multi-regional "People's Party" that emerged in the 1890s had gone through multiple iterations over a 20-year period that predated the Populist platform in 1892 and Bryan's nomination in 1896: the National Labor Union (1871), the Greenback Party (1876–84), and the Union Labor Party (1888). But none of these organizations—or even the People's Party—ever represented the full scope of agrarian insurgency. In fact, the movement often scorned electoral politics, testifying to insurgents’ lack of faith in an insular party system.

At the start of the movement, the Populist assault on machine politics began as an attack on the country's banking and currency system. The Civil War and the need to finance it, spurred a revolutionary change in the way that the nation's banks operated and, more generally, in the relationship between government and private financial institutions. These developments gave rise to a form of agribusiness that was heavily dependent on the politics of Eastern-controlled monetary policy. Family farmers owed mortgages on new land; purchased new machinery on loans; and incurred new obligations at the start of every planting season for seed and equipment, not to mention subsistence supplies to support their families until harvest. Paid once a year, when the crops came in, famers were carefully attuned to the country's credit markets. Gone were the days of simple frontier-trading: not even the most remote farmer was immune from the decisions made in the large banking houses back east. The irony, however, was that most farmers lacked access to the major networks of credit. Instead, they relied on a provincial system whereby farmers took out loans with local merchants at the beginning of the season and placed their forthcoming crop as collateral against the loan. Lack of competition, unfavorable loan terms, and high-risk market conditions produced an impossible situation. Across the country, farmers engaged in this "crop-lien" system could not sell their crop for what they owed back to the merchant. Another loan, with interest, was added to the ledger each year, tying indebted farmers to their unprofitable land and leaving them dependent on the vagaries of weather and crop prices for financing their enterprises.

Not even the most remote farmer was immune from the decisions made in the large banking houses back east.

The Populists recognized how the system of national and state party politics abetted this system of tight money and burdensome debt. The federal Homestead Act, enacted in 1862 as part of the Republican Party’s program to stimulate commercial development, made land cheap and abundant, increasing production, and depressing prices on agricultural goods. It also tied land reform to the prerogatives of party elites. New railroads, subsidized by government at all levels, brought promise of economic prosperity, but, in fact, formed a national agricultural market that made small farms further susceptible to surges in supply and lower prices. Moreover, it would be a mistake to view the late 19th century as a period of "unregulated banking." The nation's banking and currency system was highly regulated, but in favor of large banks, which held the country's debt. With a growing population, and with increased production on the farm, farmers and industrialists alike needed access to credit, which, by law, was influenced by the rates set by the U.S. Congress for how its bonds could be redeemed, and at what rate.

In 1873, a little noticed provision was inserted in a large banking bill, which served as a flashpoint in the Populist’s claim of elite intransigence. At the behest of large financial houses, the new law abolished all silver coinage, making the United States fully dependent on the gold standard. The bill passed the Congress with large majorities in the House and Senate after lengthy but superficial debate. Such a policy had the effect of constraining the money supply (making each dollar more valuable), which advantaged those who issued debt, and raised the real costs placed on holders of debt, namely, farmers. But what made this change a full-blown scandal was its surreptitious passage; few recognized, even some who voted for the legislation, that the "Crime of 73" had taken place at all. It was only when silver miners were spurned by the mint months later that newspapers and local organizations realized the full implication of Congress' machinations. The farmers plight was not solely attributed to the 1873 Coinage Act, but the bill became a clarion call for the fight against a corrupt political establishment that was all too willing to do the bidding of the nation's bankers, often in secret, without public accountability.

Both parties mobilized support by antagonizing the ethnic, racial, and regional differences of the American electorate.

The early Populists viewed the rigged money supply as a formidable obstacle to their struggle for economic justice. Likewise, they disdained partisan politics and the corruption that fueled it. While there was a two-party system that contested elections across the nation—most notably for president—most Americans, in effect, were subject to a single party that governed their state and locality. In the South, the party of Lincoln, the Republican Party, repulsed an electorate still reeling from the emotional and physical wounds of the Civil War. The Democrats owned the region, capturing the loyalties of the former confederacy with their steadfast promise to re-establish racial hierarchies and prevent black suffrage. The crop-lien system reinforced these developments, as the majority of Black Southerners were doubly disadvantaged, first by the credit system and then by sharecropping for larger land-holders. While Southern Democrats restored white supremacy, the Republicans dedicated their energies to electioneering in the North and West. Reminding voters that they saved the Union, Republicans further reinforced the geographic divisions of party competition by "waving the bloody shirt," kindling memories of a disastrous war and a contemptible former "slave power" that should be kept from public office at all cost. Where the Democrats succeeded in the North, it was because of the strength of their urban machines, which were nourished by the votes of new immigrants, many of them Roman Catholic. The Republicans excoriated the Democrats as the party of "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion", deflecting attention from the economic issues that agitated late nineteenth century American politics. Both parties mobilized support by antagonizing the ethnic, racial, and regional differences of the American electorate, and they used the spoils system and the public coffers—and sometimes outright bribes—to sustain their organizations.