Populism and American democracy

Politicians have routinely exploited the belief that the political system is rigged

Excerpted from What Happened to the Vital Center? by Sidney Milkis and Nicholas Jacobs (Oxford, 2022)

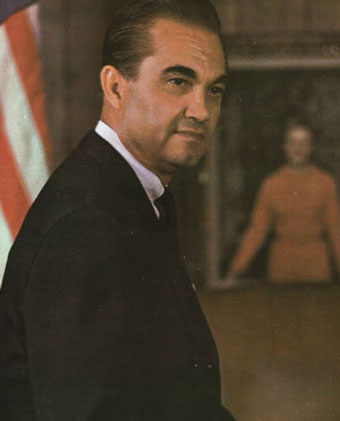

By the time he formally declared his candidacy for president, every American already knew his name. For decades, he made national headlines by defying the conventional wisdom and deriding the political establishment—attracting the ire of sitting presidents, disgusting the intellectual elite, and capturing the media's attention. His name was synonymous with a provocative style, distinguished by a thick accent, a clear sign to his followers that he was not a conventional politician. He claimed to speak for the “forgotten” American—the Americans who felt left behind by seismic cultural, economic, and political change.

In running his campaign, he trashed leaders of both parties and national heroes. In front of large banners reading “Stand Up for America!” he taunted bureaucrats, shouting that we needed to “take away their briefcases and throw them in the Potomac River!” He spoke of crime in the streets and promised that “If we were president today, you wouldn’t get stabbed or raped in the shadow of the White House, even if we had to call out 30,000 troops and equip them with two-foot-long bayonets and station them every few feet apart.” His rallies were staged spectacles. Campaign staffers ensured that a couple of demonstrators would always be able to sneak in, so that they could shout down the candidate as a fascist and a neo-Nazi. These protesters were pawns in staged political theater, allowing the leader of "real Americans" to play the strongman his followers craved: “Come on down, I’ll autograph your sandals” he would yell back. “All you need is a good barber!” “That’s right honey; that’s right sweetie pie. Oh, I’m sorry, I thought ‘he’ was a ‘she!’"

Campaign staffers ensured that a couple of demonstrators would always be able to sneak in, so that they could shout down the candidate as a fascist and a neo-Nazi.

George Wallace wanted to be president. And in 1968, nearly 10 million Americans—13.5 percent of voters—supported him.

Wallace’s assault on the “establishment” echoed a rallying cry that is endemic to American politics. As bitter and divisive as modern American politics appears, such eruptions have frequently roiled the country. Farmers in Western Pennsylvania mobilized in the 1790s and violently attacked federal tax collectors who were implementing the new government's excise tax on distilled spirits; rage spilled over this controversial tax issue and galvanized a mob of nearly 7,000 men who marched on Pittsburgh determined to raze the American "Sodom" and loot the homes of its merchant elite. Fifty years later in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, the largest riot in American history broke out in New York City in response to Congress' new draft order. White working-class residents—many of them new, impoverished Irish immigrants—were enraged by the provision that allowed wealthy citizens to buy substitutes for the draft at the cost of an average working-man's yearly salary. Anger swelled as the mob torched the homes of prominent politicians and lynched black residents throughout Manhattan. A century later, in the 1950s, anti-communist hysteria swept the nation. Lesser-known politicians, including a young congressman, Richard Nixon, took advantage of new television audiences, fabricated lists of suspected communist agents in high-level positions throughout government and society, and subjected them to vindictive hearings on Capitol Hill. Suspicion seeped out of Washington, and by the beginning of the 1960s, 100,000 dues-paying members had joined the John Birch Society—an organization formed to fight communism's spread as evidenced by developments such as the United Nations, water fluoridation, civil rights laws, and even President Eisenhower, whom they considered "a dedicated, conscious agent of the Communist conspiracy." The anger of Wallace and his followers was animated by the civil rights reform and antiwar movement of the 1960s. But like all populists, they were tapping into a deep strain of unmediated protest, which has defined the American experiment in self-government since the beginning.

Throughout American history, politicians have routinely exploited the pervasive belief that the country's political system is rigged and illegitimate.

Donald Trump is just the latest manifestation of populist rage. No doubt many readers who considered the opening lines to this book recognized some of the impulses and rhetoric of George Wallace in 1968, perhaps mistaking it for positions taken in more recent presidential campaigns. Certainly, there are important ideological differences between Wallace and Trump, and between the state-building motivations of 19th century populists, and the anti-tax, agrarian rebellions of the late 1700s. But populist politics is as much a matter of style as substance. While scholars have gone to great lengths to try and categorize populism's various iterations—reactionary versus progressive, conservative versus liberal, coercive versus democratizing—we see a common refrain. Throughout American history, politicians have routinely exploited the pervasive belief that the country's political system is rigged and illegitimate. The politically ambitious ride those periodic waves of anger, because in tearing down the institutional constraints that stifle the will of the “People," it aids their own selfish aspirations. Populism is an ancient threat to democratic politics and an obstinate problem in the practice of representative government in the United States.

While populism cuts a deep current through American political history, so too does its antithesis. Standing in its path is a form of constitutional politics—the practice of persuasion, negotiation, and compromise, the art of acknowledging irreconcilable differences, of appreciating diversity in how people want to live their own lives, and of recognizing the limits to collective action. Populism is vindictive, spurred by the desire to seek revenge on those in power because of a sense of prolonged injustice. Followers are uncompromising in their beliefs, and distrustful of those who do not share their vision of a remade future. As much as cynicism and suspicion are the hallmarks of the populist, faith in institutions and desire to persuade are necessary ingredients of spirited republican debate and resolution. Leaders of populist movements exploit the anger of disaffected citizens and offer simple solutions to complex questions. Patient, sober statesmanship is drowned out by the fury of self-righteousness that makes wise citizens look cowardly, and foolish ones courageous.

To some progressives, even as they abhor his America First vision, Trump’s image of politics accurately portrays an “establishment” that denigrates American democracy.

Donald Trump's presidency was fueled by a visceral disregard for constitutional politics. The January 6th assault on Congress to disrupt the legitimate, fair, and peaceful transition of power —one of the most celebrated features of constitutional democracy—may be the most evocative image of the present populist moment. Trump’s power, like all populist leaders, emanated from a widespread belief among his followers that the rules of the game were fundamentally rigged against them. Minutes before rioters broke through the windows of the Capitol building, the lame duck president drove home this fundamental point: “If you don’t fight like Hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore;” “When you catch somebody in a fraud, you’re allowed to go by very different rules;” “You’ll never take back our country with weakness.” It was a startling call to arms anticipated by remarks he delivered four years earlier at his inaugural address, when the newly inaugurated president sought to rally the “people” to reclaim control over their government: “For too long a small group in our nation's capital has reaped the rewards of government, while the people have borne the cost. Washington flourished, but the people did not share in its wealth. Politicians prospered, but the jobs left and the factories closed. The establishment protected itself, but not the citizens of our country.”

To some progressives, even as they abhor his America First vision, Trump’s image of politics accurately portrays an “establishment” that denigrates American democracy. The only way to defeat Trump, or a would-be emulator, they believe, is to beat him at his own game: to denounce more fiercely, mobilize more effectively, and in effect, fight fire with fire. Populism is on the rise in the United States, and globally. Leaders imbued with a populist ethos have taken the reins of power across the world, sometimes inspired by Trump’s own assault on constitutional norms and institutions. Right-wing populism has a long history in Europe; but it is startling to see this authoritarian tradition move from the margins of what was once thought to be a moderate constitutional republic to the mainstream of American politics. George Wallace never became president; Donald Trump did. In capturing power and using it aggressively, he and his followers have left an indelible print on the pages of history, charting the path forward for future movements that want to discredit any governing constraints that stand in their way.