About this episode

January 31, 2018

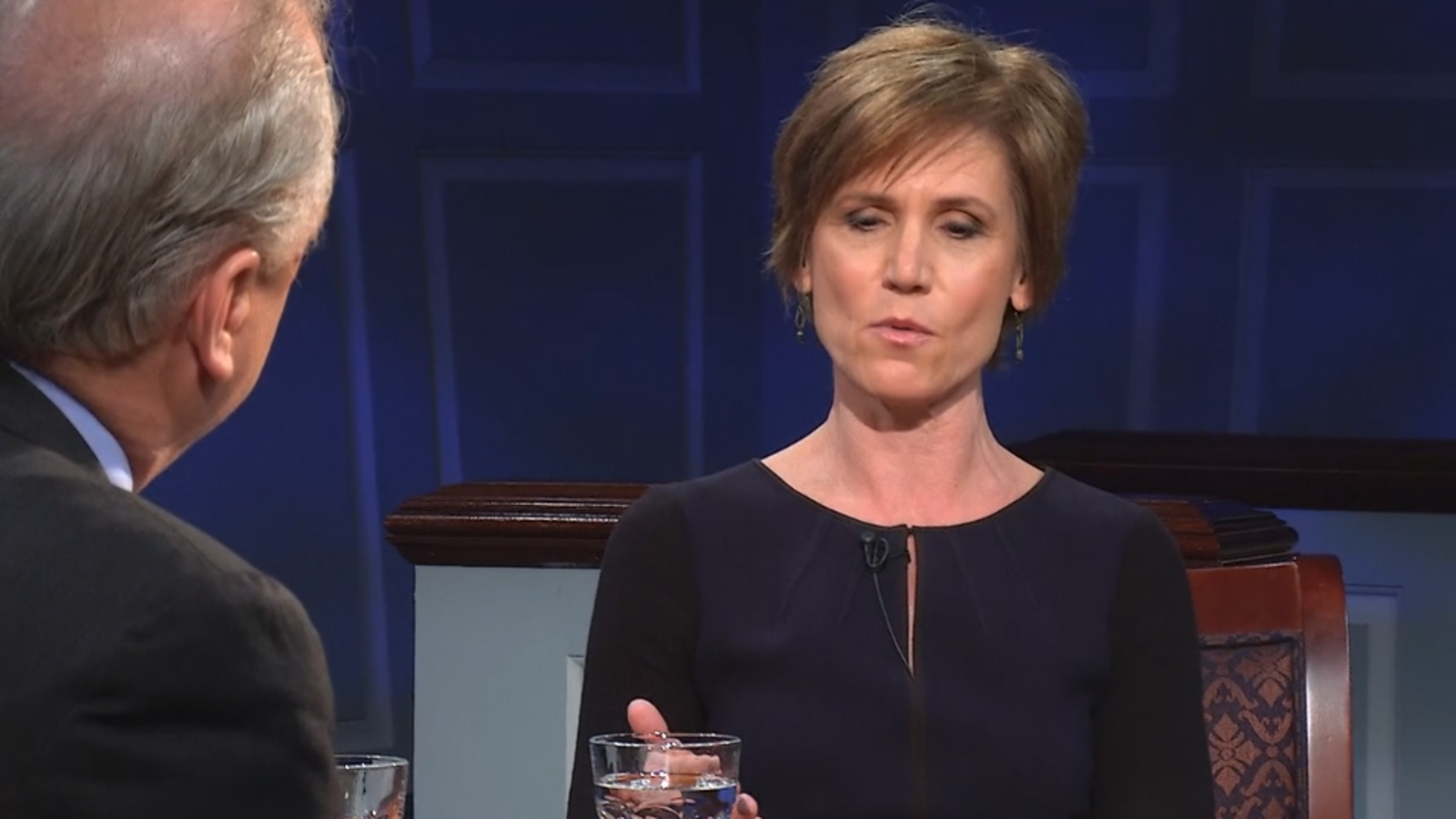

Sally Yates

Hosted by Douglas Blackmon

Barely 10 days into the presidency of Donald Trump, most Americans heard for the first time the name SALLY YATES. She was a career Department of Justice lawyer who became the acting US attorney general. But on January 30, 2017, she was abruptly fired by the president after she directed the Department of Justice not to defend his executive order restricting immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries—the so-called “travel ban.” A few days before she was fired, she also notified the White House that National Security Advisor Michael Flynn had apparently lied about potentially improper contacts with a Russian diplomat. Yates’ dismissal thrust her onto the national stage. Her calm defiance made her a hero to millions of Americans, as well as the object of criticism for many Trump supporters. In this episode, Yates discusses the rationale for why and how she stood up to President Trump.

Transcript

0:41 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. Our guest in this episode needs very little introduction. Barely 10 days into the presidency of Donald Trump, most Americans heard for the first time the name Sally Yates. She was a career Department of Justice lawyer who had served as deputy U.S. attorney general in the second term of President Barack Obama. Before that, she worked more than 20 years as a federal attorney in Georgia, most famously prosecuting local officials for tax evasion, racketeering, and corruption, but also leading a national charge against sex trafficking and many other criminal and civil prosecutions. As is customary when there is a change of administrations in the White House from one party to another, she became the acting U.S. attorney general, the highest-ranking lawyer in our government, under President Trump and was expected to serve in that role for only several weeks until Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions would be confirmed as the new U.S. attorney general. Usually, that’s not a particularly big deal, but then Sally Yates became a central figure in two of the defining issues of the Trump presidency thus far. On January 30, 2017, she was abruptly fired by the president after she concluded that his executive order restricting immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries—the so-called “travel ban”—was unconstitutional and directed Department of Justice attorneys not to defend it in court. A few days before she was fired, she also notified the White House that National Security Advisor Michael Flynn had apparently lied about potentially improper contacts with a Russian diplomat, an event at the center of the still-ongoing investigation into alleged Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. Yates’s dismissal thrust her onto the national stage, and her calm defiance in the face of an angry president made her a hero to millions of Americans and the object of bitter criticism and frustration for many supporters of President Trump. Sally, thank you for being here.

Sally Yates: Thanks. I’m glad to be here, Doug. Thank you.

02:34 Blackmon: You know, I think you’ve only done two media interviews since you testified to Congress in May. One was with Anderson Cooper on CNN. The other was with me and another reporter for the New Yorker magazine. So we’re proud to have you back at this table to do the third one.

Yates: Well, I’m really glad to be here and glad to be at UVA.

02:55 Blackmon: Before those events that I just made reference to. President Trump as a candidate had promised much more aggressive enforcement than he believed was the case under the Obama Administration both in terms of border security in general but also in terms of screening out potential terrorists who might be coming from countries that—that we may associate with terrorism. So he made those promises. He comes into office and very quickly wants to move to—to fulfill those promises and issues the—the travel ban order. He doesn't like that particular term for it, but he issues that. But how did you find out about the travel ban, that it had been issued, and then, just basically, what was your first reaction to it and how did you make the decisions that you made?

Yates: All right. So we’re going to go there right out of the gate?

Blackmon: Right out of the gate.

Yates: OK. [laughter] Well, you know, as you mentioned in your introduction that it’s a tradition at the Department of Justice for the Deputy Attorney General to—to serve as Acting Attorney General in the change of administrations. And, you know, it’s really important in all of government to have continuity, but particularly DOJ, given the national security function and the public safety function, so I was glad to do it. But there’s another tradition as well, and that is, normally, it’s a very uneventful time when you have someone in the position of Acting Attorney General in the change of administrations, that the—the unwritten understanding is that everything is supposed to stay status quo as it was until the new AG is confirmed, and so that’s what our expectation was as what this time would be like. And so it was Friday afternoon, the 27th, about 5:00-ish in the afternoon, and I was actually on my way to the airport to go back to Atlanta. My husband was getting an award at a—at a charity event that weekend, and I got a call from my principal deputy. Um, I was able to keep one political appointee with me, and the rest were all Trump appointees. I got a call from—from him saying, you know, “After you left, I went online and was sort of catching up with news,” and he went on the New York Times website. And he said, “You’re not going to believe this, but President Trump has issued some sort of travel ban.” And this was the very first that we had heard anything about this, and this was despite the fact that I was at the White House just a few hours earlier than that sitting in the White House Counsel’s office talking to them about the Mike Flynn situation. So, um, it’s all public. It’s signed. It’s done before we had been alerted at all, and we then were in a position to have to have lawyers in court beginning the very next morning defending the travel ban with individuals who were coming into the country. You know, I know it’s hard. We’re on travel ban three now, but back in travel ban one, which was the one on which I made my decision, you know, there were people who were literally in the air when the travel ban was signed and then were being turned away when they came to—to airports, and so—

FACTOID: Supreme Court allowed third travel ban to take effect December 2017

05:50 Blackmon: But so the—first, the—what’s so remarkable? I mean, an executive order is an executive order. The president—the president has the power to make these orders, and, in particular, this is one thing where the Constitution, I think, is fairly clear. You know, from the very beginnings, the president—the president has always been awarded kind of special power as far as regulating who gets to come into the United States or not. And so, you know, in some respects this seems to be right in his wheelhouse, so what was it that you would have expected him to have done other than just the status quo idea, that for—that until the new general—he should have waited until then, but if he wasn’t going to wait, if he thought it was a national crisis, if he thought that, “We’ve got to stop these bad people from coming into the country,” and that’s what it was about, then what is it that you wanted him to have done that he didn’t do?

Yates: Well, if the travel ban were truly to address a national security issue, you would have thought there would have been some consultation, then, with the national security experts, um, including those at the Department of Justice and FBI, but as well with the other national security agencies all across government. That didn’t happen. This was something that was, um—they came up with at the White House without any process at all to be able to get the input from the experts in this area of exactly what is the issue that they’re trying to address and how might they most effectively be able to address it and how might they be able to do that within the confines of the law and the Constitution. None of that happened. And so we were in a position where the travel ban has been—has been issued, and while you’re—you’re right. The president does have substantial latitude in this area, but that latitude is still constrained by the law and the Constitution. And so that’s what we had to look at over the course of the weekend to try to get our arms around, first, what is it they’re trying to accomplish with this, because the language was not very precise, um, who’s in, who’s out. Um, one of the things that was different was, at that time, the travel ban on which I made my decision actually covered people who were lawful permanent residents in the United States as well as people who had valid visas. So if you were an LPR in the United States and you had traveled abroad, you couldn’t get back in, and that was with absolutely no process at all. And beyond that I was convinced that to defend it would require me to send DOJ lawyers into court to argue something that wasn’t true, and that was that the travel ban had absolutely nothing to do with religion. And I didn’t believe that I could good—in good conscience do that, juxtaposed against the president’s statements that he had made both during the time that he was a candidate and after he was elected about his intent to effectuate a Muslim ban. So all of that came together with, “All right, this is not seeking advice in advance, but the executive order has been issued. DOJ is called upon to defend it. Can I in good conscience send lawyers in to defend it?”

FACTOID: 2015: Trump called for a “complete shutdown” of Muslims entering U.S.

I mean, this is the Department of Justice. This is not just some other law firm going in and representing any old client. This is DOJ, which is the very embodiment of our—of our justice system, and the arguments that the Department of Justice makes should always be true. And I didn’t believe that this would be the truth.

09:08 Blackmon: What would have happened if the White House had called you up, uh, or if—as you were leaving the White House that very day, uh, on January 27th, if someone had stopped you and pulled you into an office and said, “Hey, the president really wants to move on his concerns that the travel ban reflects. Uh, let’s spend a few hours here and go over this document, this order that he wants to put out. How do we do this?”

Yates: Yeah. Well, I guess the first thing I’d say is, “Let’s give it more than a few hours.” You know, I made this decision in 72 hours. That’s not really the—the amount of time that you’d like to have. This was an executive order that went to a really core founding principle of our country, that being religious freedom, and whether we are going to discriminate against people based on their religion. When you’re talking about something that consequential, I’d submit first you need more than a few hours. So, yes, I would have engaged with the administration. It’s hard to know sort of what those questions would have been, but—but you should have a more thoughtful process if—if you’re going to approach something this consequential.

10:14 Blackmon: After you resigned, uh, the White House put out a statement that said, “Sally Yates,” this is a quote, “has betrayed the Department of Justice by refusing to enforce a legal order designed to protect the citizens of the U.S. Ms. Yates is an Obama appointee who was weak on borders and very weak on illegal immigration.” The last part you probably don’t care about, but the—

Yates: I wonder who wrote that part. [laughs]

Blackmon: It does sound like the president, doesn’t it? But, uh, the idea that Sally Yates has “betrayed” the Department of Justice, how did you react to that?

Yates: Um, well, look, I mean, as you mentioned in my introduction, I was with DOJ for 27 years. I love the Department of Justice. And had I actually thought I had done something to betray the Department of Justice I would be haunted by that for the rest of my life. And so, while it doesn't feel good to have the White House making that kind of a statement, uh, I was very comfortable that rather than betraying the Department of Justice I felt like I was defending the Department of Justice and the law and the Constitution in the decision that I made. So I thought it was kind of a cheap shot, um, but I was—I was comfortable both in the decision that I made and who I was and how I had done my job.

11:28 Blackmon: So you mentioned that you were at the White House on January the 27th for another matter, that being to talk to the White House Counsel, uh, uh, McGahn and the—and you told him that, uh, these concerns had developed related to the—at that point the National—the actual National Security Advisor. But you went to see the White House Counsel to, uh—to tell him that there were public statements being made, uh, coming out of the White House, coming from the vice president, a number of other administration officials, the White House Chief of Staff and others, all saying that General Flynn, uh, when he had a phone call conversation with the Russian ambassador before the inauguration—that, uh, it was being said by the White House that that conversation didn’t include, didn’t touch on, the sanctions that had been, uh, put on Russia by the Obama Administration the day before, I think, before the phone call. Uh, and the—and what was being said was that—the White House was saying, “No, he didn’t talk about sanctions, uh, with the Russians, uh, and the vice president has been assured of that.

FACTOID: Sanctions expelled 35 diplomats, closed two Russian compounds

And so some media reporting saying that maybe he had is wrong, and there was nothing wrong with this.” So you go to the White House to say, “Someone is not telling the truth,” and that—that, in fact, uh, the FBI or someone knows what was said on that—in that phone call, and, in fact, he was—General Flynn was talking about—talking to the Russians about the sanctions. And so somebody has lied to the vice president, or somebody has lied to somebody. Uh, first off, what does it matter if—if the incoming National Security Advisor has a phone call with the Russian ambassador and they talk about something that, uh—that they don’t like that the outgoing administration has done and that the incoming administration maybe is going to do differently? I mean, what’s the problem?

Yates: Well, first, I want to be careful, because even though I know lots of people have talked about this, um, the underlying phone calls to my knowledge are still classified. And so I’m not going to get into what was actually said in—in those phone calls. So it may seem kind of artificial here given that it’s been publicly reported as much as it has, um, but I’m not going to get into that. But beyond that, you know, look, there’s nothing wrong with someone having a phone call with a representative of a foreign government as long as they’re sort of respecting the fact that there’s really one president at a time and one government at a time. And the distinction there is that you’re not supposed to be negotiating on behalf of the United States or against what the position of the United States is at that particular moment. There are potential criminal ramifications to that, and then there are ramifications beyond if, then, you go out and you misrepresent what happened in conversations and you misrepresent it not just to members of the White House, but you send people out to the American people to misrepresent to them—misrepresent meaning “lie to them”—about what was going on. That, you know—that creates a situation there where not only have you been dishonest with the American people, but you’ve created a situation where you are then compromised with the Russians, because they then have information that they can use as leverage against you and threaten to reveal that to the American people. So even once the White House knew that—that General Flynn had not been honest about that, the American people still didn’t know it yet, so the compromise still existed.

14:54 Blackmon: So the first thing is what you just described, that there can only be one president and there can only be one government, and there is a federal statute that makes it illegal to negotiate, uh, in effect on behalf of the United States with a foreign country, uh, if—if you are not the United States government. I mean, you can’t do that, and you can’t interfere with the government’s interactions with a foreign power. So that’s the Logan Act. Now, people like to say it’s never been prosecuted. Then, some people say, “Oh, it’s been prosecuted once,” but it’s not something that’s been prosecuted very often.

FACTOID: Two people indicted under Logan Act since 1799, but not convicted

Yates: Right.

15:25 Blackmon: Uh, and lots of people do informally negotiate with other countries and don’t get prosecuted criminally, but there is a statute that says you’re not supposed to do that. So that’s issue number one, but it might or might not be all that big a deal. You wouldn’t say that, but I think some might. So that’s one thing, but then the second thing is what I think a lot of people don’t understand as well, and that is that—the possibility that what you have unfolding here is essentially a Russian espionage operation. That’s one way of looking at it, but that it is in the interests of—of enemies of the United States if they end up where they’ve got someone in a very high-ranking position in the United States government where they’ve got embarrassing information, whatever it’s about, if it’s about that they don’t recycle regularly. But if it’s something that really would embarrass the official and that’s something that—that, uh, Russian espionage or whatever foreign power knows about that and has a track record of trying to use those kinds of things to influence people, then that’s the compromise, in effect. Yeah.

Yates: Right. Right, and that’s a classic Russian intel technique. I mean, they’ve been doing that for decades. That’s playbook stuff for them.

16:33 Blackmon: Yeah. I mean, the classic thing is you catch the agent in a compromising—you get a photograph of them in bed with the wrong woman, and then you, uh—and then you hold that over someone to extract information from them. But—but this could—the concern of the Department of Justice was the possibility of some sort of compromised position that the National Security Advisor could have ended up in, and that’s really the—when you go over to the White House to—to talk about this, that’s really your concern, right?

Yates: Well, there, there were multiple concerns. That was certainly at the very top of the list, and, as I testified, that’s what we kept trying to impress with the White House Counsel as to why we felt like it was so important that they do something about this. But we also felt like the White House was entitled to know that what their National Security Advisor was telling them wasn’t true, because not only were people there acting on that. I mean, the Vice President of the United States went out and told the American people something that just flat wasn’t true. We also didn’t feel like it would be fair for us to have that information and not share it with them, but at the top of our list was our concern about the compromise and their need to take action, to do something.

FACTOID: Flynn fired February 15, three weeks after Yates met with McGahn

17:42 Blackmon: But so you told McGahn that, and one of his first responses, I think—I think from things you’ve said in the past that you—he took you seriously. He listened, uh, was thoughtful about it, but then he also asked you something to the effect of, “Just hypothetically, assuming this is all true, why would the Department of Justice care whether a member of the White House administration, a member of the White House staff, had lied to another, uh, member of the White House staff, another member of the administration?” He asked you, effectively, that, right?

Yates: That was—and as I testified in the Senate, because I want to make it clear I’m not really going outside the confines of what has been public—is that that was in the second meeting. And the first day that I was over there on the 26th, there was no question like that. He certainly understood and got that this was serious business. It was when I came back the second day at his request, um, that he opened with a sort of—I’m paraphrasing here— “What’s it to DOJ if one White House official lies to another?” Um, and that’s when—

Blackmon: So what’s the answer to that?

Yates: Yeah, well, and as I’ve tried to explain to him, it’s about a whole lot more than just one White House official lying to another. We went through and explained the problem with the underlying conduct to begin with, then the fact that the compromise had been created by that second White House official going out and misrepresenting this to the American people. You know, beyond even the compromise, you’ve also got a situation where they haven’t been honest with the public about it, and that—that’s certainly an area of concern as well. But—so I walked back through all of that.

Blackmon: Did he get it?

Yates: I think—and I’ve testified before—I think he certainly both in the first meeting and in the second demonstrated an appreciation that he understood that this was serious.

19:26 Blackmon: But if an FBI agent comes in right now and stops us and starts talking to me and you, uh, and asking us questions and—and don’t read us our rights or anything, and I—and I say, “No, I didn’t stop at that bar last night and have a drink,” and in fact I did, have I committed a crime just by now answering his question truthfully?

Yates: Yeah, let me give you some friendly advice here. Don’t lie to the FBI. [laughter] That’s—yeah, that’s a crime, I mean, whether you’re—

19:53 Blackmon: What about the First Amendment? I mean, what about free speech?

Yates: The First Amendment has limitations. So you can lie to the FBI, but there are consequences for it, and that being that it’s a—it’s a violation of Section 1001. And it doesn't matter whether you’re under oath or not. Now, you know, there are limitations. If it’s a casual conversation with a friend of yours who’s an FBI agent and it’s not about an investigation, that’s not a crime. It has to be about a matter within the jurisdiction. It has to be material, so it can’t be about something that’s inconsequential. It’s not that every little shade of nuance, then, is criminalized, but if you knowingly and willfully, intentionally lie to an FBI agent in the course of an investigation about something that matters, yes, that’s a crime.

FACTOID: Trump advisor Papadopoulos has also pleaded guilty to lying to FBI

20:35 Blackmon: I tweeted out a couple of days ago, uh, just generally, “What should I ask Sally Yates, uh, uh, on American Forum?” And I did get a lot of responses to that, and some of them are things you’ve been asked many times before. I also asked Eric Holder what I should ask you, and I told you this before, but, uh—and Eric Holder said, “Ask her where she puts me in the pantheon of greatest attorney generals?” [laughter] But you don’t have to answer that, but—you did a lot of work on pardons.

FACTOID: Eric Holder was attorney general under Obama from 2009-2015

We totally understand that the president has absolute power in the case of federal charges against somebody other than him- or herself. The president can pardon that person, and that’s an unequivocal power, really. Um, uh, but the idea that you could just—if President Obama had said to you, uh, “I’d like to issue a blanket pardon preemptively of anyone who violates a law in the future that I disagree with,” could the president do that?

Yates: No. I don’t believe that the president can issue any sort of blanket pardon and not identify specific individuals and specific conduct. And any pardon from the president, as you’ve just mentioned, only goes to federal offenses. The president has no authority to pardon for state offenses.

FACTOID: A.G. Sessions: “I do not know” if preemptive pardons appropriate

21:53 Blackmon: And so the president could not say, uh, uh, “I pardon you, Sally Yates, um, for any future civil rights violations you were to commit if you became a—a government official again”?

Yates: No, I don’t believe so.

Blackmon: Yeah. Uh, but the—but al—so could the president say, “I pardon without knowing what it is. I pardon you, Sally Yates, for all your past civil rights violations that you’ve committed even though I don’t know what they are”?

Yates: You know, we never went through—the good news was, when I was serving, these were not issues that we dealt with. I—I wouldn’t think so, no, but—

Blackmon: But a preempt—I think it’s safe to—you’re saying that a preemptive pardon by the President of the United States of anybody under any circumstances would be a peculiar thing.

Yates: Oh, it certainly would be a peculiar thing.

Blackmon: And dubious.

Yates: I just don’t want to opine as to whether it’s lawful or not, whether he has the authority, without actually doing the work, um, to research that.

22:46 Blackmon: OK. Twitter questions, the main one that came back was, “Are you going to run for office?”

Yates: [laughs] No. Um, I don’t—I don’t foresee ever running for office. I believe in public service. Um, I’ve done that for a lot of years, hope maybe one day to be able to do that again, but running for office is not anything I’ve ever felt drawn to, so I can’t picture that.

23:04 Blackmon: What are you going to do?

Yates: Um, well, I’m working on that. Actually, I’m at Georgetown Law School right now, visiting there and really having a fantastic time there. The students are bright and energetic and ask really good questions, so that’s good, and I’m working on some of the issues that we’ve been talking today, criminal justice reform and some nonprofits I’m working with there and working on forming one as well as on the issues—the rule of law issues that we’re talking about here, but in terms of—just beginning discussions with people about what I’m going to do more permanently, long-term.

FACTOID: Yates penned June Op-Ed decrying mandatory minimum drug sentences

Blackmon: Forty years from now—

Yates: Yeah.

Blackmon: —what will Sally Yates, the name Sally Yates—what will it stand for in American history?

Yates: Gosh. This is, like, the “If you were a tree, what kind of tree would you be?” kind of question. [laughter]

23:50 Blackmon: You can answer that too. But what do you—what do you, uh—what do you stand for? Do you stand for a woman who stood up to a belligerent president? Do you stand for the merit of the Obama Administration? Uh, what—what do you stand for?

Yates: Well, you know, I get that the vast majority of people only know me by the acts of the last 10 days, and they wouldn’t have any reason to know who I was before as U.S. attorney or deputy attorney general or a line AUSA, but I really viewed what I did in those 10 days as—as really just a continuation of what I’d been doing all along and what I had a responsibility to do. So I hope if people look back and—and sort of have a description of who I was, it was of somebody who really took the responsibility to represent the people of the United States seriously and did the best job that I could to do that honestly and with all my heart.

24:50 Blackmon: Thank you for being here. We’d like to know what your take is on Sally Yates and the state of the rule of law under President Trump. If you’d like to tell us, share your thoughts with me via the email on your screen or on Twitter, @douglasblackmon. You can follow our guest, Sally Yates, @sallyqyates. And as always, you can visit the millercenter.org website to keep updated on news and events or visit us on Facebook to catch live tapings of the show. Finally, a reminder that only a few episodes of American Forum are left before our program goes off the air for good in early March. We hope, though, that you’ll keep watching these last few weeks, and, more than that, we hope you’ll carry our flag forward with honest, informed discussions about the issues that divide our country and listening even to the fellow citizens you most disagree with. See you next week.