About this episode

October 01, 2017

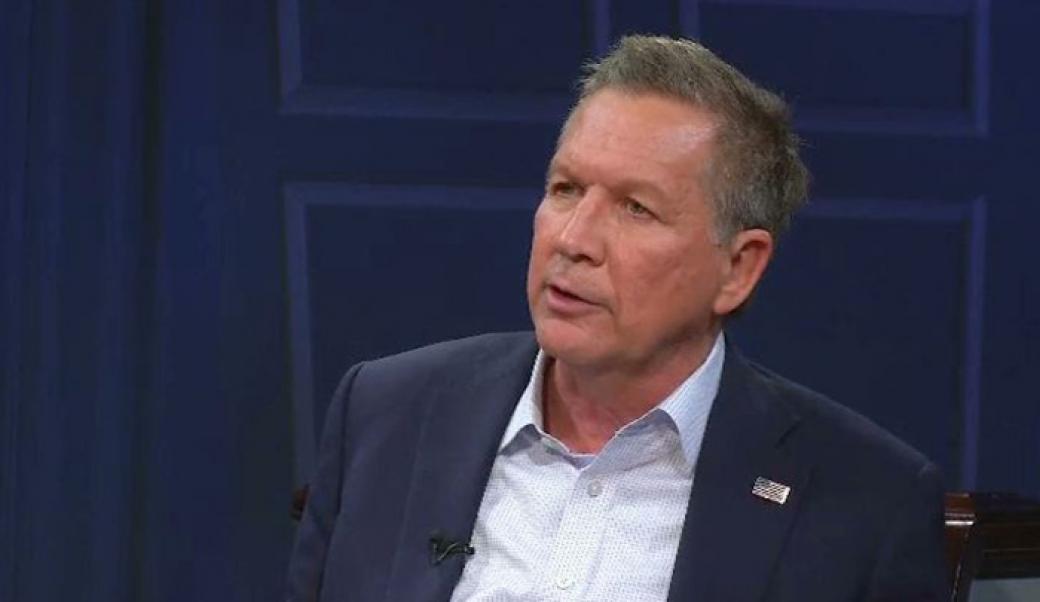

Jeremi Suri

With the expansion of technology and media, the president has become a more and more prominent figure in our daily life, while the infrastructure of the presidency is becoming more secretive. The powers of the president have increased dramatically, but recent presidents struggle to achieve their most basic goals in office. Our guest, historian Jeremi Suri of the University of Texas at Austin, invites us to look at how not just the president, but the presidency, has changed and declined over time, in his new book, "The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America's Highest Office."

The Presidency

The Rise and Fall of the American Presidency

Transcript

00:41 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. America is struggling through a bitterly divided time, in which discussions about our national leadership—especially of the president—are consumed not with careful thought and competing ideas, but acrimony, hostility, and defensiveness. More so than at any time in recent American history. A lot of that, obviously, is about the improbable election of Donald Trump. It’s no surprise that the president has been unable to consolidate broad support after losing the 2016 popular vote by a considerable margin—and winning the office only on a technicality of sorts. His performance on a number of fronts has only added to the sense among a strong majority of Americans that the president may not be up to the task of handling the severe issues that face the nation. But is the current crisis around the presidency unique to Donald Trump? Or the weird result of a flawed 250-year old constitutional mechanism that awarded the office to him, rather than the candidate clearly preferred by the majority of Americans? Our guest today says it’s much more complicated than all that. Jeremi Suri is a professor of history at the University of Texas and the author of nine books on politics and foreign policy. He’s just published a new and important volume entitled: The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America’s Highest Office. In the book, he argues that the complexity and size of our government, and the scale of the domestic and international challenges facing the nation have simply overwhelmed the office—and left the American people so viscerally unsatisfied with our national chief executives that the election of “ultimate outsiders” like Donald Trump—stems partly from a rejection of the office itself. To fix that, he says we have to find a way as a nation to fundamentally redefine the most powerful position in the world. Thanks for being here.

Jeremi Suri: Thanks for having me on.

2:40 Blackmon: So your book, even though some people would say—people who are critics of President Trump would say this book must have the title of The Impossible President as opposed to the Presidency, but it’s really not about Donald Trump. It’s about the history of the office, how it has changed over time, and let’s start with that, because your subtitle is The Rise and Fall of America’s Highest Office.

Suri: Yes. Yes.

Blackmon: But tell us about the rise. What do you mean by that?

Suri: Well, the presidency begins as this largely vague and unformed office. The founders could not agree on what the president would do, and, in fact, they assumed that the House of Representatives would choose the president. Their vision was that every big state would nominate a favorite son. The favorite son would be, uh, chosen by electors in that state, and eventually the House of Representatives would have to decide. That, of course, rarely happened. Over time, the office has grown as those in it, from Washington to Jackson to Lincoln to Theodore Roosevelt to Franklin Roosevelt, expanded the powers of the president to serve the needs of American society in different moments. So with Lincoln, it’s not just winning the Civil War; it’s creating the infrastructure for a modern capitalist economy. With Theodore Roosevelt, it’s creating a set of progressive reforms that manage that economy, and with Franklin Roosevelt it’s healing the hard edges of that economy and mobilizing a society across class and race for warfare. And for 150 years, this vague office, because of its vagueness, is able to grow and serve the needs of the public. That’s the rise of the office.

04:05 Blackmon: There’s more to the story than just how the New Deal and the creation of this modern state with some modern social security systems built into it, however one feels about that, but the invention of this truly modern government, but that, yes, all along the way—you talk about Jackson as well, the way that the presidency is elastic enough to go from—I think it’s about a page and a half of text in the Constitution of which only maybe a paragraph defines the presidency.

Suri: Right. Right.

Blackmon: And you go from that into this very different kind of office, but always in tandem with the way the economy is evolving, and the presidency seems to be up to the task of this evolution.

Suri: Well, one thing I certainly learned studying the presidency closely is that for our first 150 years we have a remarkable range of individuals in office. Uh, few of them are geniuses, and they’re all flawed, deeply flawed, but they’re also men of enormous talent. And here’s the really important point; they’re men who, once they’re in office, really believe it is their job to serve the whole country. Uh, we are actually blessed in that respect, and so the office—and this is one of the points of my book—the office defines the individual as much as the individual defines the office. One of the problems, Doug, with a lot of the work we have on the presidency is that it tends to be very individualistic and very biographical, and there’s nothing wrong with that. We have wonderful biographies of presidents. You’ve featured many of the authors on your wonderful show, but nonetheless, when you focus on an interview, you overemphasize the role of the individual. My argument is that we need to understand how the car, how the machinery of the car has changed over time as well as simply understanding the drivers.

Suri: In many ways, this is—this is Roosevelt’s legacy. Uh, he’s the hero of my book, but he’s also a tragic figure. Roosevelt creates the modern presidency. It’s the culmination of the work of those before him, but he creates the modern presidency in terms of his domestic reach. He’s the first president to make home calls through the radio, and he also creates a world historical presidency, a president who is going to be responsible for defeating fascism across the globe and rebuilding the world.

FACTOID: First Fireside Chat in March, 1933 discussed national banking crisis

That creates expectations that Roosevelt can barely meet, and those expectations and requirements continue to grow, grow exponentially after he leaves office. And if a Roosevelt can barely do it, when you have other talented men who might not have all the skills and experience he has, that makes it incredibly difficult. John F. Kennedy aspired to be Roosevelt. In fact, one of the first things he did—I talk about this in the book—is bring together scholars who had studied Roosevelt, people like Arthur Schlesinger, Richard Neustadt to advise him on how he could be Rooseveltian. And the irony is that, in trying to be Rooseveltian, it actually set him up for many, many failures because he was trying to do too much. Again, it was barely possible for Roosevelt to do it. Now, he was trying to do much too much. I show in the book, uh, how, for example, during the Cuban Missile Crisis how he’s trying to do so many things. He’s now stuck and scheduled into so many responsibilities that it’s very hard for him to find the time he needs to do the deliberative work that has to be done to figure out whether we’re going to blow up the world.

6:58 Blackmon: Yeah, and that's—and that particular observation is one that I certainly—we’ve talked about at this table in other regards, but this notion that, uh—that we’ve become a society that—and certainly everything since 9/11 has been an example of this—where we take on this extraordinary challenge that is a version of trying to fulfill Kennedy’s promise—

Suri: Yes. Yes. Yes.

Blackmon: —in his inaugural address and is an honorable one—

FACTOID: JFK was inaugurated as the 35th president on January 20, 1961

Suri: Yes.

Blackmon: —to try to defeat these terrible forces in the world, but we do it in a way where we say to the American people, “We’re not actually going to ask you to sacrifice. We’re not going to sell war bonds. We’re not going to make—ask you to pay for this. What we want you to do is to keep going to the mall and let the professional fighters do this thing over here.”

Suri: Right.

Blackmon: And I’ve long thought that a lot of the dissention we have in the country now, things might be rather different if there had been a more authentic mobilization of all Americans, uh, in the aftermath of 9/11 like there was in World War II.

Suri: Right. And I—and I think this is a really important point I’m trying to make in the book, which is that during the rise period, presidents are doing more and more, but there are really a few big things that still define who they are, and those are the moments when they turn to collective sacrifice. Roosevelt begins by asking the American people to work with him, to sacrifice to help solve the Depression, and to help move forward in fighting fascism. He doesn’t begin by telling Americans what to do. He begins by asking them to join in. And as presidents start to do more and more things, they—instead of doing that, which takes a lot of work, they look for easier, quicker solutions. What I find in the second half of the book, in the period of the fall, is that presidents are often more concerned with getting problems off their desk than actually solving them. And that, of course, reflects our own lives. We are busier than ever before and accomplishing less, and that’s manifest in the president as well as all of us as citizens.

8:43 Blackmon: And you write—in reference to Kennedy and Johnson, uh, you write, “Johnson and Kennedy ultimately, over the course of this decade,” their decade, “Johnson and Kennedy were unable to rise above their crises and congested calendars,” that’s something that you come back to over and over again, “above their crises and congested calendars, a turning point when the power of the modern executive grew almost unmanageable and certainly unsatisfying for leaders and citizens alike.”

Suri: We have spent a lot of time studying presidents, but one set of materials we haven’t spent a lot of time are their calendars. How do they organize their time? We have every day of every president’s administration going back to Herbert Hoover, and so I spent a lot of time with these calendars, and what you see is really quite extraordinary. Franklin Roosevelt’s calendar is not very full, and it’s a handwritten calendar. Missy LeHand writes things in. There’s a lot of time for him to think. There’s a lot of spontaneity. Kennedy is a turning point. From Kennedy forward, the calendars are typed up. They’re organized by 50-minute intervals by a large staff, and presidents are less in control of their calendar, less in control of their time. And as you look at these calendars, you have to ask yourself, “When on Earth do they think? When on Earth do they have time to actually deliberate on what they’re doing?” Lyndon Johnson’s calendar for the day he sends American combat forces to Da Nang, March of 1965, is about 12 pages long, 12 pages, minute to minute, phone call to phone call. How on Earth can we expect people to make big decisions in that environment?

FACTOID: Marines were deployed to Da Nang to defend a nearby U.S. air base

10:05 Blackmon: And so, then, we get out of the Johnson years, and then we—you fast-forward—you focus next on Reagan and the—another transformative president in many respects, though exactly what the transformation was is a point of some debate, (laughter) uh, but who comes in office with a very clear sense of mission—

Suri: Yes.

Blackmon: —again, an activist of his own—by his definition but who then is consumed by a series of unpredictable events.

Suri: Precisely.

Blackmon: Exactly, the invasion of Grenada, the things that turn into Iran–Contra.

Suri: Yes.

Blackmon: A lot of foreign policy dimensions to all of that, and that—but you—but then, he ends up as this great negotiator with the Soviet Union or, you know—great in the sense of “consequential”—negotiator with the Soviet Union over nuclear weapons, becomes very genuinely concerned about the danger of a nuclear holocaust, and you say he restored a historic veneer, you know, that he did bring back this sense of importance and power of the presidency. But, again, behind the curtain it’s a somewhat different story.

Suri: Precisely. Reagan was one of the most interesting chapters for me to write. I had read a lot and even written a lot about him, but, again, going back to the primary materials you see so much new. Uh, what’s extraordinary about Reagan is that he comes into office understanding this problem. I think what I’ve argued, what we’ve talked about, he actually understood. His goal was to make the president less of a micro-manager and to focus on a few big things, but what happens over his presidency is he gets pulled into more and more. It’s as if he’s trying to drive the car one way, and the car pulls him in another direction. And very quickly, you find the machinery of government pulling Reagan into a set of illegal activities that he knows about that he should be held responsible for but that are not places that he expects that he’s going to end up, and that defines his presidency as much as anything else.

FACTOID: Lebanese newspaper Al-Shiraa broke Iran-Contra scandal in 1986

I think it’s overwhelming evidence that even when you’re trying to liberate yourself from the incredible responsibilities of the office, the office drags you in, which is why I think we need to talk about reforming the office, not looking for Superman to solve the problems.

12:07 Blackmon: But then, after that, through the Reagan era and then even more so under Clinton, the government does, in fact, get quite a lot smaller, and so the advocacy for the shrinking of the government as a response to the deficit is actually another way in which the job of the president is getting more and more complicated, congested.

Suri: Absolutely.

Blackmon: But the power of the government to actually—as a force in the economy and the society is actually getting smaller.

Suri: This is a great point. One way to look at it—and I try to talk about this in the book—is that there’s a lot of power the president has, but the power often doesn’t match the responsibility.

Blackmon: Yeah.

Suri: And we can see that in foreign policy as well. President Obama had enormous capabilities, scary capabilities to kill people, to assassinate people, and he did around the world.

FACTOID: Obama-ordered drone strikes killed nearly 4K, including 324 civilians

But he was called upon to actually bring stability to the Middle East. So you can assassinate people, but it’s not really clear that that’s actually making the region more stable. So there’s a disconnect there, which is part of the complexity of our system, but it’s something we don’t talk about because we focus on the individual, and we assume the individual will figure that out. My argument is that, in fact, these are structural problems that individuals will not figure out. We need to change the structure to match the needs. Form should follow function.

13:20 Blackmon: The current era of the presidency, I think, we would say begins with the Clinton presidency in which all of these forces you’re talking about begin to catch up and begin to overwhelm the—

Suri: Yes. Yes. Yes.

Blackmon: —and we have—you have this great phrase. You call Clinton and Obama “magicians of possibility,” which is not completely a compliment. It sounds—

Suri: Right. Right.

Blackmon: —it sounds lovely, but it’s not really a compliment. (laughter)

Suri: I’m glad it sounds lovely.

Blackmon: But whether we like those individuals or not, I think we can agree that they are two people of great intellect and great charisma—

Suri: Yes. Yes. Yes.

Blackmon: —and they had—which is how they became president. But it was interesting to me, as well, because, you know, I was a young newspaper reporter in Arkansas in the 1980s.

Suri: Wow.

Blackmon: And so I was telling someone yesterday or the day before that I first met President Clinton in 1981, I think.

Suri: Wow.

Blackmon: And I would tell people in other parts of the country about this guy, or people would ask me about him. And I would sort of jokingly comment that in Arkansas the governor is not really the governor. He’s the mayor of the state.

Suri: Absolutely. I think one of the real problems that Clinton and Obama both faced as enormously talented figures is that they got to where they are by always over-promising themselves, and that made them attractive to an American public coming out of the Cold War that felt, you know, we needed some change, but we can’t really talk about how to change the institutions, so we’ll put these surrogates in there to do this for us. But, of course, the institutions eat them alive, and that’s what I talk about. It’s not that they didn’t have certain successes. It’s not that they were bad presidents, but they far underperformed because it took them so long—and I try to show this—to understand how different it was being president from being governor of Arkansas or being a senator from Illinois.

Blackmon: An obscure legislator. Yeah, right.

Suri: Yeah, it’s totally different. One of the biggest challenges every president faces is that they come into office, they have all this power, and they can’t get anything done. And what do you do then, right? That doesn't happen to the mayor of Arkansas. That doesn’t happen to a senator in that way. So the expectations were so high, and, as I try to show, they made a lot of missteps because they didn’t understand how the system worked. And what happened then is that empowered their opposition. They already had—we have to be honest and say they confronted opposition for a reason—a number of reasons I describe in the book, including race and class. They confronted overwhelming opposition, but they also made it easier for their opposition in their small steps.

Blackmon: Yeah, and the—and that opposition takes on a character that’s somewhat different, but it is a fascinating thing that there has always been this strange contradiction in American government that—even someone like Bill Clinton. He’s governor of Arkansas over many terms, dominates a decade of the history of that state. The budget is balanced for that state every single—every budget. There’s always a budget every year. The mechanisms of government, as is the case in almost every state—

Suri: Right.

Blackmon: —every year, the budget is balanced in almost every place. And then, someone who comes out of that, I mean, Clinton was an extraordinarily more prepared though, in reality, a rather unprepared figure to be president. But compared to Barack Obama, he’s eminently more qualified. Barack Obama had no real resume of qualifications to be President of the United States except his intellect and charisma. So you look at someone like Clinton who, after this long period of very efficient governance, then becomes President of the United States and presides over a government that has fantastic deficits and can’t—you can’t do any of the things that could be done at the state level.

Suri: Right.

Blackmon: It seems like that’s back to your point of proportionality.

Suri: Absolutely. Scale and scope matter. So it’s not that being governor of Arkansas is easy, but if you’re incredibly smart, energetic, and you have a few good people around you, you can do a lot relatively quickly. It’s much more difficult because of the range of responsibility and the range of resistance when you’re President of the United States. Clinton’s effort to get beyond that was to use the same skills that worked in Arkansas, which did not always work in office. That’s, by the way, why both Clinton and Obama actually become a lot better in their second terms because it takes them that long to learn the system. But then, the paradox is that once you’re in your second term you have a lot less leverage because you’re not running again.

17:25 Blackmon: So that brings us to President Trump. Your book is really not about him, only a little bit that refers to him at the very end, but you do call him—you say, “The impossible presidency produced a truly impossible president.” What do you mean by that?

Suri: Well, in part it’s still—I still can’t believe he’s president, so that’s part of it. (laughter) Uh, the impossible presidency produced an impossible president because I think Americans became so fed up with the office for good and bad reasons that they literally chose someone to blow it up, or at least 62 million people voted for someone, and the one thing that seems to unite all of them is that they thought he was going to blow up and transform this office. And the only way—we know this as historians. The only way institutional reform happens is when people get into the system who understand the system, respond to pressures outside the system, but actually change it with knowledge of what the system is.

FACTOID: Trump first publicly promised to “drain the swamp” in October 2016

And that’s not going to happen here, and look at what has happened so far with President Trump, especially in foreign policy. What has he done? He’s turned foreign policy over to the military. This is the most military-dominant government we have had in American history, full stop. Now, uh, I think the military officers he’s chosen—Mattis, McMaster, and others—these are fine people. These are people who understand the Constitution. They are not going to stage a coup or anything like that, but the whole point I’ve been making is that our government is too keyed to power, particularly military power. You've put the military power—people in charge, right? It’s like putting the people who eat candy in charge of the candy store, right? This is a problem here, and so what’s happened is, people voted for someone to blow up the office, and the person who’s blowing up the office is actually reinforcing all of the worst elements of it.

19:07 Blackmon: Now, you also, at the end, uh, offer some potential solutions to that. They’re not terribly detailed, uh—

Suri: No, because I’m better on problems than solutions, as my wife will tell you.

Blackmon: (laughs) But the—and one of them you’ve already referred to, that—the need for most investment in these institutions that can be bulwarks against this collapse in confidence around basic facts and basic truth and so, uh, that there need to be these strong analytical organizations that are part of the government, public media, but the government invest in these alternatives to the—to the unreliable, uh, flood that we all live in now.

Suri: Right. If I might just clarify just to build on that, my point is that, uh, right now the providing of information to the public is often keyed to revenue generation. I have nothing against people doing things for revenue, but the whole point of a public media and the whole point of public universities would be that the incentive structure is not to release knowledge that generates revenue but, instead, release knowledge that enhances public understanding. And some will says, “OK, well, NPR is a little biased in one direction.” I don’t think it is, but that’s fine.

FACTOID: Two-thirds of Americans cannot name the three branches of federal government

We could have two of them, right? But we should have institutions that are incentivized to provide knowledge to the public, not to make money but for the sake of the knowledge itself. That’s a big distinction, and we’ve moved away from that. And I think we could change that, and it would cost next to nothing. It’s a few aircrafts.

20:32 Blackmon: Yeah, well, and it’s—and the same sort of thing about universities and school systems, which is another breakdown, I think, from where we once were. Now, the American was—for such a long time had a very clear understanding of teaching civics. Now, it was only to teach civics to white kids and middle-class kids and leave out everybody else for the longest time, but the—and partly, it seems, it was when we began to actually fulfill the obligation—

Suri: Yes.

Blackmon: —to offer education to everyone that we began to pull back from the importance of it and the resources that would go into it. But that tradition that through education—that that’s the place that we can instill some—what these core, shared values are that maybe would have an effect on all the things we’ve been talking about.

Suri: Yeah, and for universities, if I might say, this is the real risk in turning our pub—our great public institutions like the University of Virginia over to revenue sources that are private sources. That’s a real danger. That has a big effect. People think we can do that and that these institutions will be the same. No, they’re changing before our eyes in the same way that Fox News is different from the BBC.

Blackmon: Yeah. Well, and sometimes people will say—you know, I write a lot about and talk a lot about mass incarceration and law enforcement issues and things, and sometimes people will ask me after an event somewhere—they’ll say, “Well, what can we do? How can I change things?” And I’ll say, “Well, the first thing is that you have to confront that wherever you live you don’t pay enough taxes,” and I mean that on a local level—

Suri: Yeah, absolutely.

Blackmon: —that people—we have—we’ve so starved institutions like the public schools in almost every community in America in part because, again, the sort of self-obsessed citizen thing of being really—I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had neighbors come over to me and say they went down to the court house and appealed their property tax appraisal, and they got 150 bucks shaved off of their property taxes, and what a great thing that was. And I finally have begun to say, “You know, that’s actually not a good thing.”

Suri: We actually have enough money in the system. Let’s take the city of Austin. I know a lot about this now through my wife who’s a member of the city council in Austin, and the city of Austin has doubled its property tax base in the last 10 years. There’s a lot of money there, but too much of the money is actually given away to the wrong people. So not enough money goes into the school system, and much more money goes to incentives for “developers.” Now, why we need to incentivize developers who are falling over themselves to build new units in Austin I don’t quite understand, so it’s not even just about taxing. It’s about how we use the money we have.

Blackmon: And so that part of your fix, uh, relates to the people, to have a better electorate of more informed, more engaged, more serious citizenry. But the other side of it is how to actually change the office of the presidency. I mean, how do we do that? What is something that we can take off the plate of the president that really matters and give to somebody else? How do we do that?

Suri: Well, so I’ve done some comparative work on this as—as many others have, and I realized—I hadn’t realized this until I wrote this book—we’re the only major democracy in the world that still does that, that still thinks there should be one person.

Blackmon: One king.

Suri: One king, right? Most of our peer democracies—India, Germany, France—they actually have a president or a Bundeskanzler and a prime minister. Now, the prime minister technically is part of the legislature, but the prime minister has a cabinet and an executive government they form. And what works well in those societies is that there is some division of responsibility. So in Germany, the Bundeskanzler does most of the policy work, but the head of state work, which takes a lot of time of presidents—entertaining people, visiting foreign dignitaries, a lot of that—is done by the president, not the prime minister.

FACTOID: Bundeskanzlerin (“Chancellor”) Angela Merkel was elected in 2005

In France, of course, we have a division where the president does more foreign policy and the prime minister does more legislative work. I think President Obama would have been far better off if he had a prime minister rather than a vice president, a prime minister who had legitimacy, accountable to the American people, even one of a different party, who could manage the legislature. Let me give a contemporary example. Right now, I am convinced that, uh, House Speaker Paul Ryan would like to do different things than he is doing, but he is held hostage by, really, a handful of Republican Congressmen in his Congress—and this is what Boehner was complaining about, right—who, if Ryan doesn’t do exactly what they want, they will take their votes away. He’ll lose his Speakership. So a very small number of extreme, non-representative—for the country—members of the House are controlling the House agenda. If we had the equivalent of a Speaker who was elected by the country and was not accountable to a small part of his party, he could do very different things, and we’d have a very different set of legislative issues coming out. And paradoxically, I think we’d have less gridlock between the President and Congress in that context. That is how it works in other systems. We would benefit from that. That would obviously need a constitutional change, but I think that’s the direction we have to go. We have to at least be honest, Doug, that the office is too large for even the most talented man in the world. And, as we know, we don’t always have the most talented man in the world in there. (laughter)

M1: Or woman.

Suri: Or woman. Thank you. Or woman.

Blackmon: Jeremi Suri, thanks for joining us.

Suri: Thank you for having me

Blackmon: If you’d like to join our conversations about national security, politics, the presidency—any of the central issues in American life today—go to the Miller Center Facebook page, visit MillerCenter.org, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @douglasblackmon. You can follow today’s guest @JeremiSuri. And please keep watching us on your local PBS affiliate. I’m Doug Blackmon. See you next week.