Changing the Unwritten Rules of Presidential Leadership

Extraconstitutional norms shift when the president decides and the country agrees

On June 29, 2023, reacting to a series of Supreme Court decisions in which all six Republican-appointed justices outvoted their three Democratic-appointed colleagues, President Joseph Biden lamented that “this is not a normal court.” Asked if he would support the proposal by progressives within his party to expand the court from 9 to 13 justices, however, Biden dismissed the idea as a “mistake” that “doesn’t make sense.”1

Nine the court would remain, even though nothing in the Constitution limits Congress’s authority to alter its size by statute. But unlike those calling for change, Biden had learned the lesson of FDR’s failed effort to “pack the Court” in 1937: nine justices, although not part of the “capital-C Constitution” (the document itself), are still part of the “small-c constitution”—the extraconstitutional rules of the game that also govern how the political system is supposed to work.2

Or perhaps Biden overlearned that lesson. In truth, multiple changes in the small-c constitution have occurred during the past two centuries, but only after they were animated by changes in norms and their accompanying customs and expectations.

Multiple changes in the small-c constitution have occurred during the past two centuries, but only after they were animated by changes in norms.

Presidents have often animated these changes. In the Miller Center–sponsored book The Presidency: Facing Constitutional Crossroads, I discussed 10 such changes, tracing each to its historical origin. In this essay, I illustrate the argument with three: Andrew Jackson and the veto, Theodore Roosevelt (TR) and the “rhetorical presidency,” and Jimmy Carter and the creation of the modern vice presidency.3

Andrew Jackson and the Veto

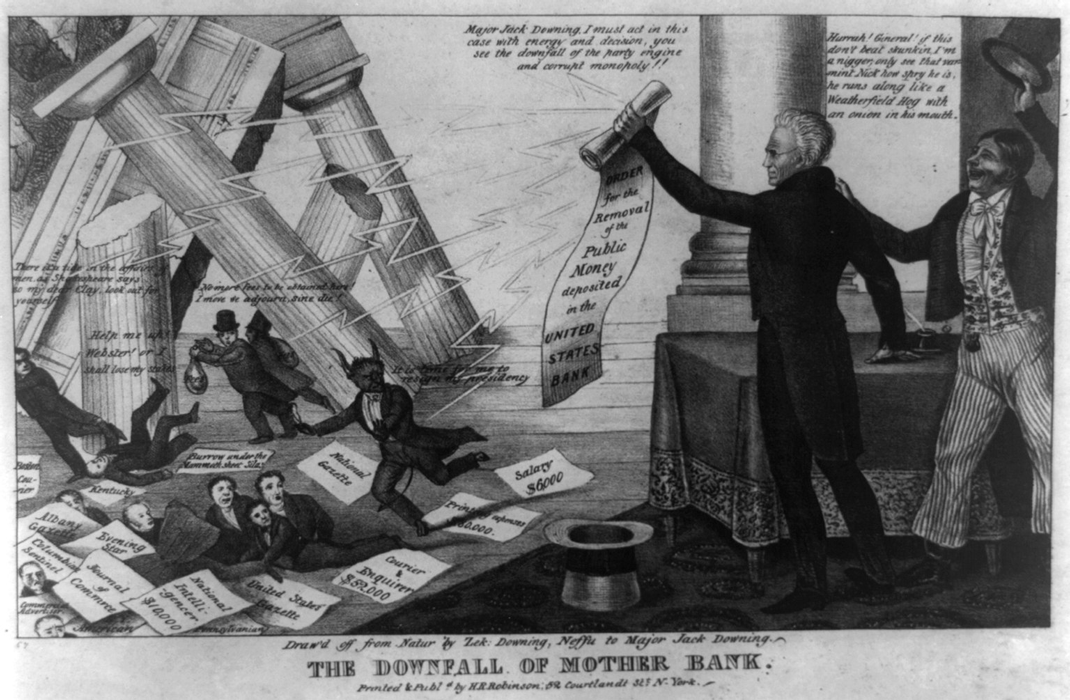

Jackson’s veto of the bill Congress passed in July 1832 to renew the Second Bank of the United States was politically important at the time. It has remained important as a precedent-setting extraconstitutional norm concerning how presidents should exercise the veto power.

Jackson regarded the bank as the leading institutional bastion of everything he opposed, especially favoritism for the Eastern financial elite.

Jackson’s veto of the bill Congress passed in July 1832 to renew the Second Bank of the United States was politically important at the time. It has remained important as a precedent-setting extraconstitutional norm concerning how presidents should exercise the veto power.

Sen. Henry Clay of Kentucky, Jackson’s Whig opponent in the forthcoming 1832 election, was so confident that bank renewal would be a winning issue that he persuaded Congress to extend the bank’s charter, four years before the existing charter was set to expire.

Although nothing in the Constitution provides any guidance about when vetoing a bill is appropriate, all of Jackson’s predecessors used the power sparingly. As the first president, George Washington established the norm that vetoes should be reserved for legislation that was of doubtful constitutionality. In the 40 years after he took office in 1789, Washington and his five successors vetoed just 10 bills, most of them minor.

Jackson interpreted the veto power differently, grounding his view in a new and expansive conception of presidential leadership. The president, Jackson believed, was a more authentic representative of the people than Congress—the only person in government who was elected by the entire electorate. Consequently, Jackson regarded the president’s judgment that an act of Congress was unwise policy as sufficient ground for a veto.

Jackson interpreted the veto power differently, grounding his view in a new and expansive conception of presidential leadership.

In his veto message, Jackson argued that the bank was an “odious” institution and that “good policy” was reason enough for him to act.

His veto survived a congressional vote to override.4 Five months later, Jackson vanquished Clay, the bank’s leading advocate, by 219–49 in the Electoral College and 54 percent to 37 percent in the popular vote.

Jackson’s veto—and, just as important, the country’s agreement that it was properly cast—altered the existing norm of presidential deference to Congress and established a new norm that has endured ever since.

Jackson’s veto—and, just as important, the country’s agreement that it was properly cast—altered the existing norm of presidential deference to Congress and established a new norm that has endured ever since.

Jackson’s veto—and, just as important, the country’s agreement that it was properly cast—altered the existing norm of presidential deference to Congress and established a new norm that has endured ever since. Jackson vetoed 12 bills in eight years, more than all of his predecessors combined. The new norm for presidential use of the veto power was that presidents should feel free to exercise it regardless of whether they think a bill is constitutional. Jackson’s 39 successors have taken advantage of this transformation of the small-c constitution, casting a combined total of 2,568 vetoes, only 112 of which—barely 4 percent—have been overridden by Congress.5

TR and the “Rhetorical Presidency”

To say that presidents in the 18th and 19th centuries were seen but not heard is an overstatement—but not by much. Presidential candidates were expected to stand, not run, for office, remaining silent while partisan allies campaigned on their behalf. Once in office, ceremonial speeches such as the inaugural address were acceptable, but speeches urging Congress to enact legislation or criticizing Congress for failing to do so were widely regarded as inappropriate.

Although nothing in the Constitution either encouraged or forbade presidential rhetoric aimed at influencing public opinion, the norm of reticence was no less binding for being unwritten.

Speeches urging Congress to enact legislation or criticizing Congress for failing to do so were widely regarded as inappropriate.

In 1868, Andrew Johnson was the target of two articles of impeachment for speeches “attempt[ing] to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach the Congress of the United States.”6

One-third of a century later, the public was ready for a different style of presidential leadership. The rise of powerful national corporations had caused more people to turn to the national government—in particular, to its most visible institution, the presidency—to provide a countervailing source of power. In response, Roosevelt ushered in what political scientist Jeffrey K. Tulis has called the “rhetorical presidency”—that is, the use of popular rhetoric as a principal tool of presidential leadership.7 Its origins lay in Roosevelt’s campaign to persuade Congress to enact the Hepburn Act, a bill to enhance the regulatory power of the federal government over the nation’s railroads.

The public was ready for a different style of presidential leadership.

The act was opposed by conservative senators in the president’s own party, who managed to stifle it in committee. Roosevelt decided to appeal “over the heads of the Senate and House leaders to the people who were masters of both of us.”8

TR’s speechmaking tour of the country had the desired effect, and the Hepburn Act was passed into law in 1906. The small-c constitution’s unwritten rule concerning presidential rhetoric gave way to the new unwritten rule that “going public” is part of the president’s job description.9

The small-c constitution’s unwritten rule concerning presidential rhetoric gave way to the new unwritten rule that “going public” is part of the president’s job description.

The subsequent arrival of radio, then television, and then social media as means of mass communication only enhanced the rhetorical presidency.

Jimmy Carter and the Modern Vice Presidency

Not every American admires Congress, agrees with the Supreme Court, or supports the president. But, except for the vice presidency, no constitutionally created office has been the object of ridicule. Even some vice presidents have ruefully joined in the fun. John Nance Garner, who was FDR’s first vice president, famously declared: “The vice presidency isn’t worth a pitcher of warm piss.”10

Historically, the vice presidency’s main problem was rooted in its original design. The Constitutional Convention assigned the vice president just two duties: to preside over the Senate (a role that is significant only when a tie vote needs to be broken) and to step in if something bad happens to the president, which it usually does not. These duties stranded the vice president in a constitutional no-man’s land, somewhere between the executive and legislative branches and fully at home in neither.

These duties stranded the vice president in a constitutional no-man’s land, somewhere between the executive and legislative branches and fully at home in neither.

President Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976 launched a change in the small-c constitutional vice presidency that has endured even though the Constitution remains substantially unaltered. During the half-century that followed the office grew both in prestige and influence. Much of the credit for this transformation lay in the agreement forged between Carter and Vice President Walter F. Mondale in response to a memo that Mondale wrote to Carter on December 9, 1976, six weeks before the beginning of their term.

Mondale knew from conversations with his political mentor, former vice president Hubert H. Humphrey, how marginal a job the vice presidency could be. Mondale’s memo to Carter proposed that his primary role be as “general adviser” to the president, consulted on virtually every matter that crossed the president’s desk. As vice president, Mondale argued, he was in a “unique position” to perform this role as “the only other public official elected nationwide . . . able to look at the government as a whole.”11

Mondale’s memo to Carter proposed that his primary role be as “general adviser” to the president, consulted on virtually every matter that crossed the president’s desk.

To make his advice useful, Mondale continued, he would need access to the full range of information that Carter received, a professional staff, the right to participate in all important meetings and, most important, “access to you” in the form of weekly private sessions and an office in the West Wing of the White House.

As a former state governor with no experience in Washington, Carter realized that he needed a vice president with federal experience to help him meet the challenges of his new job. Mondale had served two terms in the Senate when Carter selected him as his running mate. He approved Mondale’s memo in full, not just on paper but in practice throughout his presidency. Subsequent presidents, most of them with little Washington experience themselves, and vice presidents (most of them with considerable Washington experience) have accepted the new norms concerning the vice presidency and institutionalized them.12

Subsequent presidents, most of them with little Washington experience themselves, and vice presidents (most of them with considerable Washington experience) have accepted the new norms concerning the vice presidency and institutionalized them.

Conclusion

In obvious ways, the development of the American presidency has been affected by amendments to the Constitution concerning, for example, presidential disability and the two-term limit. In less obvious ways, the small-c constitutional presidency has also evolved. It has done so when a president decides the time for change is right and the country agrees.

The framers’ design of the presidency was clearly a sketch more than a blueprint. But in ways that involved adapting norms concerning the office to changing times and circumstances, the small-c constitution has enabled the capital-C Constitution to fulfill what James Wilson—the most influential delegate to the Constitutional Convention on presidential matters—identified as the main qualities that the executive was meant to bring to constitutional government: “energy, responsibility, and dispatch.”

Endnotes

Holly Otterbein and Zach Montellaro, “Biden Still Won’t Nuke the Court. But He Is Upping His Criticism of It,” Politico, June 29, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/06/30/biden-supreme-court-reform-00104484.

On FDR and the Supreme Court, see Michael Nelson, Vaulting Ambition: FDR’s Campaign to Pack the Supreme Court (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2023).

Michael Nelson, “Crossroads of the (C)onstitutional Presidency: How Ten Extraconstitutional Landmarks Shaped the Office,” in The Presidency: Facing Constitutional Crossroads, ed. Michael Nelson and Barbara A. Perry (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012), 28–48.

Andrew Jackson, “Veto Message [of the Reauthorization of Bank of the United States]” (July 10, 1832), American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/veto-message-the-re-authorization-bank-the-united-states.

United States Senate, “Vetoes, 1789 to Present,” https://www.senate.gov/legislative/vetoes/vetoCounts.htm.

U.S. Congress, “Articles of Impeachment Exhibited by the House of Representatives” (March 4, 1868), American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/articles-impeachment-exhibited-the-house-representatives.

Jeffrey K. Tulis, The Rhetorical Presidency (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987).

Theodore Roosevelt, The Works of Theodore Roosevelt, vol. 20 (New York: Scribner’s, 1926), 342.

Samuel Kernell, Going Public: New Strategies of Presidential Leadership, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007).

The oft-quoted “warm spit” in this statement is the G-rated version.

“Transcription of 1976 Carter-Mondale Memo”: https://www.politico.com/f/?id=00000173-eae0-d94e-a1f7-eef110b00000

Sidney M. Milkis and Michael Nelson, The American Presidency: Origins and Development, 1776-2021 (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2023), chap. 15.