It’s not just the economy, stupid

Running for president in 1992, Governor Bill Clinton wanted his campaign to focus on domestic reforms. With world affairs looking so favorable to American interests—the Soviet empire had collapsed, Eastern Europe was free, a great allied coalition had defeated Iraq in the Persian Gulf War—Clinton did not challenge George H.W. Bush on foreign policy. “It’s the economy, stupid,” his campaign manager, James Carville, famously exclaimed. It worked, and Clinton entered the White House with a clear domestic agenda to increase jobs and economic growth.

Within months of becoming president, however, Clinton learned that the world would not cooperate with his domestic agenda. In Clinton’s first year, Washington confronted a cascade of small challenges that threatened American regional interests and called upon the nation’s humanitarian conscience. During the early fall of 1993 alone, the president had to respond to the death of 18 American soldiers in Somalia, the failure of an American military vessel to dock in Haiti because of protesting crowds, open military conflict between Russian president Boris Yeltsin and the democratically elected parliament of his country, and rising tensions on the Korean peninsula as the dictatorship in Pyongyang pursued a nuclear arsenal. Civil war and ethnic cleansing intensified in the former Yugoslavia, and Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein continued to defy international sanctions by rebuilding his military, tightening his grip on power, and rewarding the families of terrorists in Israeli-occupied territories. Terrorist threats to American citizens, soldiers, and allies also increased during this period, with numerous sponsors—including an emerging network around a wealthy Saudi radical, Osama bin Laden.

Bill Clinton’s domestic preoccupations left his administration unprepared for these multiplying challenges. Like President Kennedy before him, Clinton intended to rely on his instincts rather than organized planning or preparations for foreign crises. He believed his predecessors had succeeded when they “made it up as they went along.”

But Clinton’s first year proved that even the most talented politician cannot improvise a clear and effective foreign policy strategy. To lead abroad, a president must begin his or her time in office with a disciplined effort to define interests and goals, anticipate threats, link resources [means] and objectives [ends], and organize appropriate resources across a labyrinth of U.S. government agencies.

I think there probably should have been more time spent on the first hundred days and what did we want to accomplish, what was going to face us and how are we going to deal with it, what was our strategy for the first hundred days, three months, or whatever period you want to choose.

Clinton’s inattention to these strategic issues from his postelection transition through his first months in office set him back significantly. He had respected and knowledgeable advisors, but he allowed them to operate without clear guidance or a disciplined policy process. They were each making it up as they went along, rather than working together toward common foreign policy goals. The president’s own scattered, overconfident, and ever-shifting style transferred into his policy process, with damaging consequences for the country in the long term.

What were the priorities for American security in 1993? What were the emerging threats and how could the United States best protect itself against them? Unfortunately, President Clinton did not demand clear answers to these questions. With his focus on domestic economics, and his desire to avoid other hard choices and distractions, President Clinton encouraged continued foreign policy superficiality during his first year. “Soft” security issues—including drug trafficking, free trade, and environmental protection—became backdoor routes for giving more attention to domestic needs than traditional international concerns. The avoidance of geopolitics started with the president’s inaugural address.

Clinton famously explained to the nation: “There is no longer a clear division between what is foreign and what is domestic.” Although that was true, he framed that observation for his administration to justify making foreign policy around popular concerns at home, rather than external developments requiring more American attention. Trade policy was a primary example. Clinton created the National Economic Council (NEC) to act as a counterpart to the National Security Council. The NEC worked with Secretary of Commerce Ron Brown to promote American manufacturing and exports abroad. Opening markets to help American companies and workers was, for Clinton’s first year in office, his primary foreign policy goal. It served domestic American interests, but not necessarily the foreign needs of allies and developing states with struggling economies of their own. The president’s basic assumption was that a cultivation of prosperity at home would, more than anything else, elicit the same abroad as the nation’s model shined beyond boundaries. “Our greatest strength is the power of our ideas, which are still new in many lands,” Clinton said in his inaugural address on January 20, 1993. “Across the world we see them embraced, and we rejoice.”

Clinton’s slogan, as you’ll recall, was, ‘It’s the economy, stupid.’ His view of the economy was not simply confined to the domestic economy as though it operated in isolation, but also a view of the international economy. Clinton…saw immediately the connection between U.S. domestic economic health and our participation in a globalizing world.

The international sources of resistance to these ideas evaded clear analysis during most of Clinton’s first year because the president wanted to trumpet the seamless global benefits of his domestic program, and he did not want to address geopolitical challenges to it. He did not make a major statement about international inequality, ethnic conflict, or terrorism during his first year, despite the prevalence of these challenges, especially in southeastern Europe and the Middle East. The president also ignored rising threats from what his NSC advisor later called “backlash states”—Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, in particular. Clinton preferred to talk about markets, democracy, and civil society.

All of Clinton’s foreign policy advisors understood the president’s willful optimism, and many shared it in the afterglow of communism’s collapse in Russia and Eastern Europe. They sought to champion American liberal capitalist values in different ways, similarly over-stating American influence and underrating resistance. They acted sincerely but not systematically, avoiding challenging evidence and alternative scenarios. They refused to contemplate the possibility that American ideas and practices might not work for particular regions. They ignored the accumulating evidence that religious and ethnic sectarianism trumped democratic alternatives in Slobodan Milosevic’s Serbia, Hafez al-Assad’s Syria, and countries like Haiti and Burma under military rule. Recognizing the obvious limits of the American model and contemplating alternative programs for security and stability—that was a realist heresy for an administration that wanted to manage a smooth tide of expanding markets and deepening democracies.

Undisciplined wishful thinking made the United States reactive at best, and crisis prone at worst. The Clinton administration did not calibrate its grand aspirations to effective actions; it did not match capabilities to goals. What was the plan for spreading democracy in poor, authoritarian regions? What role would the U.S. military play? How would the administration align trade policy, aid efforts, public diplomacy, and force? Instead of coordinating the tools available to the White House for effective action, the administration repeatedly assembled ad hoc responses to conflicts it had not anticipated. This happened repeatedly during the unfolding civil war in the former Yugoslavia and the emerging crises in Somalia, Rwanda, and Haiti.

So there’s a lot of fault to go around in Somalia. Number one, the policy types like me, the policy makers like me, did not act more forcefully on our conviction that we were headed in the wrong direction. I also think there’s some fault that lies with the military for not really owning the troops that we had on the ground.

Presidents cannot predict crises, but they can formulate a coherent framework to integrate their resources for maximum achievement of objectives. Without such a framework, the Clinton administration spent its first year either running to place Band-Aids on international wounds or denying that wounds existed. This reactive U.S. approach allowed small international actors to become the agenda setters in southern Europe, Africa, and many other regions.

Beyond disorganization and distraction, the Clinton administration suffered from a very vague conceptualization of its goals. What kind of world did it want to help create? How did it expect to get there? Abstraction increases confusion when it elides rather than elucidates difficult policy choices.

My estimate is [Defense Secretary Les Aspin] probably did not engage the president much on [Somalia]. I think the president was blindsided by what happened in Somalia.

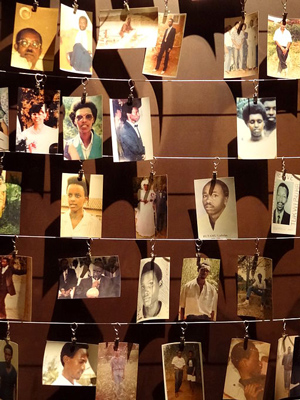

Civil wars in Yugoslavia, Somalia, and Rwanda proved the vagueness of the Clinton administration’s thinking and its harmful effects. Candidate Clinton accused President Bush of doing too little to address post-Cold War ethnic conflicts, but in each of these cases the Clinton administration was unable to marry its rhetoric about democracy with peacekeeping initiatives that encouraged favorable outcomes. In Yugoslavia the Serbs and Croats expanded their ethnic cleansing efforts, as the White House failed to orchestrate an effective multilateral response. In Somalia, Clinton inherited a humanitarian intervention, under United Nations direction, that exposed U.S. Army Rangers—deployed as protectors for aid workers—to urban guerilla warfare that resulted in 18 American combat deaths and few positive results on the ground. Scarred by the events in Somalia, six months later President Clinton refused to deploy force when Hutu militias in Rwanda killed more than 500,000 Tutsi and Hutu citizens, as UN peacekeepers helplessly watched the genocide.

Then the cliché is that because of Somalia we did PDD 25 [Presidential Decision Directive], establishing the rules about peacekeeping, and then decided not to intervene militarily in Rwanda, even though there was a genocide, because we were so scared by Somalia. There’s some, but only some truth to that, at least for me.

Market democracy and multilateral peacekeeping seemed to mean very little as ethnic conflicts triggered civil wars in Europe, Africa, and other areas. The Clinton administration’s humanitarian claims also appeared hollow. National Security advisor Anthony Lake defended the administration for being “principled about our purposes but pragmatic about our means.” No one within government, however, could explain what that meant in practice. Vagueness contributed to confusion about American foreign policy aims. Without direction, it was impossible to allocate American resources effectively.

The diplomats and soldiers involved in Yugoslavia, Somalia, and Rwanda felt this confusion, and by early 1994 relations between the White House, State Department, and Defense Department had reached a low point. The forced resignation of Secretary of Defense Les Aspin after the one-year anniversary of Clinton’s inauguration was an admission of policy dysfunction. Anger with American leadership spilled into Congress and the public at large. Foreign policy vagueness contributed to infighting (even within the Democratic Party) that also detracted from the domestic effectiveness of the president. Focusing on the economy, at the cost of serious foreign policy thinking, was ultimately counterproductive.

In May 1993 the American undersecretary of state for policy, Peter Tarnoff, inadvertently confirmed the rising cynicism of Clinton’s critics when he admitted that “economic interests are paramount.” Explaining why the United States was not doing more in the former Yugoslavia or other regions, he pointed to deep budget deficits and unmet needs at home, claiming, “We don't have the money.” Of course, the United States had more money than any other international actor. The question was how Washington would spend its resources, and Clinton’s first months gave little indication beyond the very limited economic concerns that Tarnoff articulated. Clinton’s early record looked less like the foreign policy of a superpower than the economic aggrandizement of a once-prosperous society.

The Clinton administration was not isolationist, but its behavior and behind-the-scenes comments made its internationalism thin, self-serving, and ultimately ineffective. The combination of idealistic rhetoric and strategic uncertainty turned vague words into frustrating sources of disillusion. Samantha Power was one of many young liberal journalists to blame Clinton for raising expectations about ending authoritarianism and then denying the “problems from hell” that accompanied political change. Watching the genocide unfold in Rwanda as a college student, this author was stunned by the incompatibility between the ideas trumpeted by Clinton and U.S. inaction as thousands of innocents died.

During the summer of the administration’s first year, National Security advisor Anthony Lake shared this concern about the contradiction between the administration’s lofty rhetoric and its weak actions. He expressed frustration with the president’s distraction from foreign policy and the divisions within the administration over key conceptual issues. After more than a half-year of directionless international activity, with very few meetings among principal officials, Lake sought to bring strategic coherence to policy. He labored under the burden of having to make order not just of the future, but also of the early months of near-chaos. Strategic thinking becomes more difficult to initiate as an administration accrues a record that it feels obliged to defend. The longer a president waits to formulate a strategy, the harder it becomes. The early part of the first year is the best window for clear and coherent thinking, but it closes very fast, as Lake learned.

President Clinton and many others perceived Lake’s strategic exercise as an effort to “brand” foreign policy with a simple and persuasive slogan. That perception was important, but it was misguided. Rigorous strategy defines core interests, threats, and priorities, and it helps to align resources accordingly. For a nation as large and powerful as the United States in the early 1990s, the evident tendency was to overreach and underperform. Strategic thinking promised to restore some needed discipline to policy choices. President Clinton understood this, but he did not see it as a priority, even after months of foreign policy disarray in the White House.

In a speech delivered on September 21, 1993, Lake articulated a “strategy of enlargement—enlargement of the world’s free community of market democracies.” The strategy had four components, according to Lake: strengthening the “community of major market democracies,” consolidating “new democracies and market economies,” countering aggression, and pursuing a “humanitarian agenda.” The goals remained vague, and the means for achieving them were largely unspecified. This language underpinned the “National Security Strategy of Engagement and Enlargement,” officially released by the Clinton administration nine months later, in June 1994.

Defining a strategy was progress, and it helped the Clinton administration in future years, but “engagement” embodied many of the policy shortcomings evident since inauguration. Spreading market democracies was an old Wilsonian goal, as Lake admitted. It continued to elide the difficult choices any president must make about where and how to use American resources abroad, and how to judge the effectiveness of those resources. “Engagement” was an aspiration, but it was not a strategy because it did not provide guidance for defining priority interests and assessing the most important threats. Even at the pinnacle of its unipolar advantage in the early 1990s, the United States could not expect to spread market democracy everywhere at all times.

How should the president choose where and when to emphasize democratization over other objectives? That crucial question remained unanswered through the close of administration’s first year. Few presidents could match Bill Clinton’s political skills. He won election to the nation’s highest office on a promise to deliver domestic economic gains (“it's the economy, stupid”), but that promise was insufficient, and frequently a diversion, from the demands on his attention as commander in chief.

Clinton’s troubled first year teaches that a new president must prepare himself and his closest advisors to enter the White House with a clear set of realistic foreign policy goals (based on core national interests), a rigorous assessment of threats, and a disciplined process for aligning resources. The president must formulate a coherent agenda for a complex international landscape very quickly, or else a multiplication of foreign demands will define his policy for him. The president must then use his first year to apply and adjust his strategy through a continual process, which he directly manages, for reassessing interests, goals, threats, and resources.

In contrast to Clinton’s instincts, foreign policy requires consistent presidential focus, and any new commander in chief must manage a coherent and disciplined policy-making process from his first days in office. He must sit at the table as the first among equals. Foreign policy appointments are among the most important that the new president makes because the commander in chief needs trusted advisors who can help him assess numerous threats and implement his goals, despite contrary pressures. Most important, rigorous high-level thinking about foreign policy goals is necessary early in an administration to set a favorable course, signaling to U.S. government agencies the goals they should pursue and the programs they must prioritize. Clinton’s disappointing first year is a warning against the perils of a presidential transition that assumes the focus of the successful campaign—where issues are separated and simplified—is the same as the focus for successful national leadership, where integration and management of complexity are crucial.

Domestic interests connect closely with foreign policy, but they are not synonymous, and one cannot subsume the other. A new president must be ready to give the complexities of foreign policy—not just the slogans—serious attention. It’s the strategy, stupid.

Resources

- President Clinton’s National Security Strategy Statement, February 1995: http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/doctrine/research/nss.pdf

- NSC Adviser Anthony Lake’s speech at Johns Hopkins University, 21 September 1993: http://fas.org/news/usa/1993/usa-930921.htm

- Jeremi Suri, “American Grand Strategy After the Cold War’s End to 9/11:” http://jeremisuri.net/doc/2009/03/orbis-article-fall-2009.pdf

- Charlene Barshefsky Interview, Miller Center

- Samuel R. Berger Interview, Miller Center

- Anthony Lake Interview, Miller Center

- William Perry Interview, Miller Center