I was one of the 'Ritchie Boys'

Not long before his death in 2020, a renowned legal scholar reflected on his escape from Nazi Germany—and how growing up in a fascist regime shaped his life and work

It was 1934, Hitler’s second year in power. My parental home since my birth in 1921 was Offenbach am Main, Germany’s leather-goods center, where I attended an elementary co-ed public school. The bell rang for the customary 20-minute recess, and I hurried out into the courtyard with my fourth-year classmates to play a bit of fussball, when one of the latter smashed my chin, yelling, “Dirty Jew!”

“What did you do that for?” I exclaimed, struggling to get to my feet. He yelled, “You are a dirty, slimy Jew!”

Reporting the disconcerting incident to my parents that evening, I cried out, “I can’t stay in this country anymore; please send me to America.” At the age of 13, I already realized that the United States represented to me the epitome of a free society.

At the age of 13, I realized that the United States represented to me the epitome of a free society

Four years later, my wonderful, determined mother had convinced FDR’s anti-Semitic State Department that I would not be a threat to the United States, and I received my visa with intention to become a citizen. Over the strenuous objections of my German father, a WWI-decorated veteran of the Kaiser’s army, twice-wounded at Verdun fighting the Americans, I left my parents and younger brother in April 1937 for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where I would live as a refugee with an American Jewish family. My parents and brother followed in 1939, my father’s health broken in the concentration camps of Sachsenhausen and Dachau following Kristallnacht in November 1938. He would die in Pittsburgh, an American citizen, in 1951.

Though considered an enemy alien after Germany declared war on the United States in December 1941, I was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942. As author Bruce Henderson observed in his national bestseller Sons and Soldiers: The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned with the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler, “War planners in the Pentagon soon realized that the German Jews already in uniform knew the language, culture, and psychology of the enemy best and had the greatest motivation to defeat Hitler.” I was among the 1,985 of these German Jews selected to form a top secret “force to help win the war in Europe.”

German Jews already in uniform knew the language, culture, and psychology of the enemy best and had the greatest motivation to defeat Hitler

Camp Ritchie in Maryland became the legendary center for training, in eight-week sessions, an elite force of fluent German- and French-speaking intelligence commissioned and non-commissioned officers. I was among them and particularly happy that we were fast-tracked for U.S. citizenship before being sent overseas to interrogate German POWs and liberated French citizens.

Seven years after I had escaped the Nazis’s grasp, I returned—as a Ritchie Boy, American citizen, and U.S. Army 2nd lieutenant—to my birthplace, war-torn Offenbach au Main, and attended a poignant service in my boyhood synagogue. I sat in a pew with my elementary school teacher, a Protestant, holding my hand throughout the liturgy. His support of my studies had cost him his job in 1934.

I sat with my elementary school teacher, a Protestant, whose support of my studies had cost him his job in 1934

I devoted my life and career to the study of constitutional law and history because I had learned firsthand how quickly a democracy can devolve into a dictatorship.

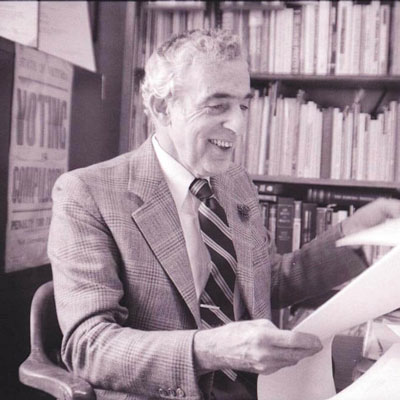

Henry Abraham was a leading scholar on judicial processes, particularly the U.S. Supreme Court; a close friend of several Supreme Court justices; and a beloved professor at the University of Virginia and the University of Pennsylvania. The Miller Center supports the annual Henry J. Abraham Distinguished Lecture, which was established in 1999 by his students, colleagues, family, and friends to honor him.