The Civil Rights Act of 1964

July 2, 1964: LBJ signs one of the most far-reaching laws supporting racial equality in American history

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed racial segregation in public accommodations including hotels, restaurants, theaters, and stores, and made employment discrimination illegal. President John F. Kennedy first proposed the bill on June 11, 1963, in a televised address to the American people announcing that he would send a civil rights bill to Congress. His bill would become the basis for the most-far reaching act of legislation supporting racial equality since Reconstruction. President Lyndon Johnson signed the bill on July 2, 1964. This exhibit summarizes some of the historical events that influenced the passage of this legislation.

The Civil Rights Movement

African Americans had been fighting for equal rights throughout US history, but the 1955 bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, catalyzed the modern Civil Rights Movement. When Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger, the Black community organized a boycott of the city buses. After 13 months, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Alabama’s laws segregating buses were unconstitutional, and the boycott ended in success.

Leading the boycott was the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose actions made him a regional and national figure. In early 1957, he was one of the founders of the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC), which was created to coordinate and support non-violent protests against segregation and discrimination.

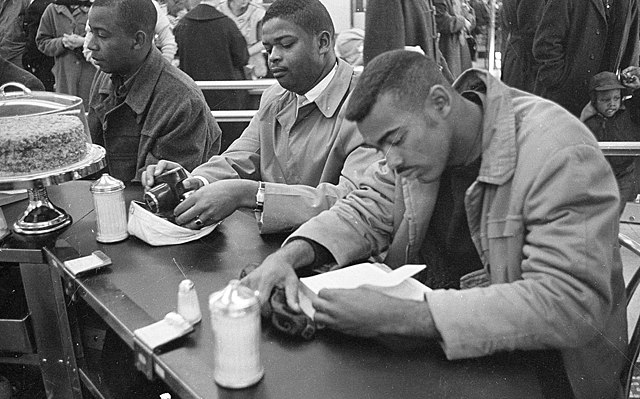

The Civil Rights Movement was a grassroots effort that took shape as Black citizens decided to speak up, walk out, or engage in civil disobedience to bring attention to the racial injustices that permeated Southern society. In February 1960, four Black students in Greensboro, North Carolina, began the sit-in movement, when they refused to leave a segregated lunch counter at a Woolworth’s store. Their actions set off a wave of sit-ins and other non-violent protests against segregation. Later that year, students founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as an outlet for younger African Americans who wanted to take part in the movement.

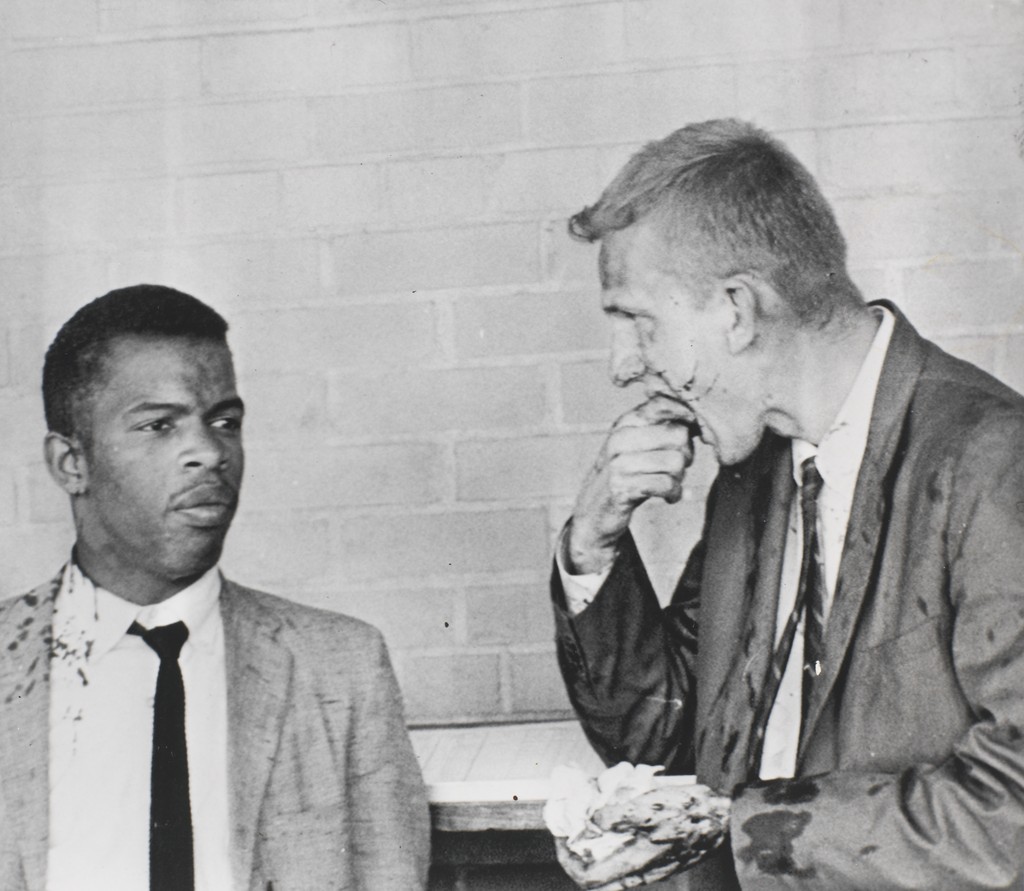

In 1961, the Freedom Riders risked their lives trying to desegregate interstate travel facilities, such as buses and bus stations across the South. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that segregation in interstate travel was illegal in two cases: Morgan v. Virginia in 1946 and Boynton v. Virginia in 1960. Yet, throughout much of the South the rulings were ignored and unenforced. Beginning their rides in Washington, DC, the freedom riders were arrested in Charlotte, North Carolina, and they encountered increasing resistance as they traveled deeper into the South. In Alabama and Mississippi, the riders were beaten and arrested. There were multiple waves of freedom riders, and the riders appealed to the federal government for protection.

The next year, violent vigilantes rioted in Oxford, Mississippi, as James Meredith, by order of the U.S. courts, enrolled in the traditionally white University of Mississippi. Federal troops were necessary to restore order so that Meredith could enroll at Ole Miss.

The Kennedy Administration

Although John F. Kennedy’s administration responded to civil rights protests that turned violent, such as sending federal troops to the University of Mississippi campus to quell the riots, it was criticized for not doing enough to support African Americans fighting for social and economic equality. President Kennedy wanted to wait until his second term to send a civil rights bill to Congress, but events conspired to constrict his timetable.

By the spring of 1963, simultaneous protests were taking place throughout the South, but the one attracting national and international attention occurred in Birmingham, Alabama. The city’s Black community decided to follow a strategy used in Albany, Georgia, protesting discriminatory practices with mass marches and filling up the city’s jails. Birmingham’s Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, a hardline segregationist, responded to the peaceful protests with police force.

As photographs of police dogs attacking peaceful marchers and fire hoses being turned on children flashed across the country and around the globe, President Kennedy was spurred into action. In May 1963, the administration sent Burke Marshall, an official from the Justice Department, down to Birmingham, and he negotiated a short-lived agreement between business leaders and civil rights activists.

That same month, on May 18, 1963, President Kennedy delivered a speech at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, in which he mentioned the movement and the struggle for equal rights. He referred to the complexity of the problem and the importance of assuring all Americans their rights under the law.

Then on May 21, federal courts ordered the University of Alabama to admit two African American students, Vivian J. Malone and James A. Hood, for the summer session beginning in June. The governor of Alabama, George Wallace, was an avowed segregationist. In his inaugural address in January 1963, Wallace “drew a line in the dust and toss[ed] the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny,” declaring “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” He pledged to block the entrance and prevent the university’s desegregation.

Read Wallace’s full Inaugural Address from the Alabama Department of Archives and History Digital Collections.

President Kennedy warned Governor Wallace against stopping the integration of the university, but on June 11, 1963, Governor Wallace stood in front of a university building to bar Malone’s and Hood’s entrance. Governor Wallace and U.S. Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach engaged in a standoff, captured on camera, and President Kennedy mobilized the Alabama National Guard to protect the students and resolve the situation. Malone and Hood ultimately entered the building and registered for classes.

That night President Kennedy took to the air waves, speaking forcefully about civil rights. He announced his intention to ask Congress to act, declaring that a moral crisis existed in the country and requesting Congress to move forward with legislation to desegregate public accommodations and speed up the integration of public education.

[This nation] was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that the rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.

Watch the full-length televised address from the Miller Center’s Presidential Speech Archive.

On June 19, President Kennedy sent his civil rights bill to Congress. As the bill began to slowly make its way around Capitol Hill, civil rights leaders proposed maintaining the momentum by reviving an idea from the 1940s. In 1941, A. Philip Randolph and associates had proposed a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in the war industries. The march never happened because President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order that prohibited discrimination in national defense industries.

Read President Roosevelt's Executive Order 8802 at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

In 1963, civil rights leaders, including A Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King, Jr., Roy Wilkins, James Farmer, and Bayard Rustin decided to revive the original idea. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took place on August 28, 1963, when more than 250,000 demonstrators gathered in Washington, DC, in support of job creation and civil rights legislation.

Following the peaceful March on Washington, which featured King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, President Kennedy met with civil rights leaders at the White House. They discussed the event and the details of the civil rights legislation moving through Congress. Roy Wilkins, who led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), expressed their desire to have fair employment practices included in the civil rights package. They also stressed the importance of training and education.

The optimism following the March on Washington was shattered on September 15, 1963, when a bomb went off in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Four young Black girls were killed in the explosion: 11-year-old Cynthia Wesley and 14-year-olds Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, and Carole Robertson.

Four days later, civil rights leaders traveled to Washington to meet again with President Kennedy. In an excerpted recording of their meeting, Dr. King voiced the frustration and fear in the Black community, while President Kennedy stressed the importance of keeping the support of the White community to get Congress to pass a civil rights bill.

On September 23, 1963, President Kennedy met with several White officials from the city of Birmingham. He urged them to appreciate the difficulties that President Harry Truman faced when he integrated the armed forces in 1948. He also acknowledged the difficulty of integrating secondary schools, but he pushed back against the idea that desegregating public accommodations was too difficult.

The Johnson Administration

Then on November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated while riding in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas. On becoming president, Lyndon Johnson took up the mantle of civil rights. In addressing a joint session of Congress five days after the assassination, President Johnson announced his intention to continue to pursue the passage of civil rights legislation as a tribute to President Kennedy.

Using his leadership to lobby key lawmakers, President Johnson forged a bipartisan coalition of northern and border-state Democrats and moderate Republicans. The House passed the bill in February. In the Senate, Johnson and his allies tried to offset a coalition of southern Democrats and right-wing Republicans, who launched a lengthy filibuster, to get the bill passed.

On June 19, 1964, President Johnson called Democrat Hubert H. Humphrey, Jr. of Minnesota who was the floor leader in the Senate to ask about the bill’s status. He began the conversation asking about Humphrey’s son who had just been diagnosed with cancer. While the two men talked, other U.S. senators made their final statements on the bill. Almost an hour later, the bill passed in the Senate by a vote of 73 to 27.

A few days later, on June 22, 1964, President Johnson called House Minority Leader, Republican Charles Halleck of Indiana, to discuss bringing up the Senate version of the bill for a vote in the House. Passage of the bill required significant cooperation from Republicans in Congress. Johnson urged Halleck to pass the civil rights legislation, as well as his anti-poverty bill. Alternatively cajoling and joking with Halleck, Johnson made it clear that he planned to sign the act before the July 4th congressional recess.

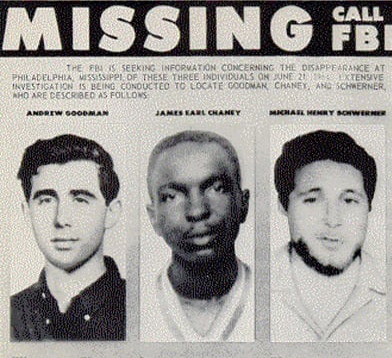

Amid his efforts to push the Civil Rights Act, President Johnson was juggling a variety of other competing demands. On June 21, three civil rights workers in Mississippi who were working on registering voters as part of Freedom Summer went missing after being arrested near Meridian, Mississippi. The next day, civil rights activists contacted the U.S. Justice Department to expand the federal presence in the state to search for the three men. President Johnson soon became involved in trying to find the young men.

Explore the Miller Center’s Mississippi Burning exhibit.

On July 2, 1964, a few hours before the House passed the Senate’s version of the bill, President Johnson and Attorney General Robert F. “Bobby” Kennedy discussed the advantages and disadvantages of when to sign the Civil Rights Act. Kennedy raised concerns about celebrations during the Fourth of July holiday weekend and the potential for violence, while Johnson made the case to sign the bill right away before Republicans left town for the holiday and their national convention. He wanted Republicans to be part of the signing ceremony since the bill was a bipartisan effort that would not have passed without their support.

About an hour later, President Johnson called Roy Wilkins to ask his advice about when he should sign the bill. They agreed that there should be no delay, and the president should sign the act as soon as the House passed it. They also noted that many Republicans were leaving Washington, and they would appreciate being able to be part of the signing ceremony before they left.

On the night of July 2, 1964, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in a televised White House ceremony. In his remarks, he noted the historic nature of the legislation and outlined his plan to implement the law. At the conclusion of his statement, he signed the bill using an estimated 75 different pens, which he then passed out to the bill’s supporters, including Senator Humphrey, Attorney General Kennedy, House Minority Leader Halleck, and Dr. King.

We believe that all men have certain unalienable rights. Yet many Americans do not enjoy those rights.

Watch the full-length televised address from the Miller Center’s Presidential Speech Archive.