About this episode

May 21, 2017

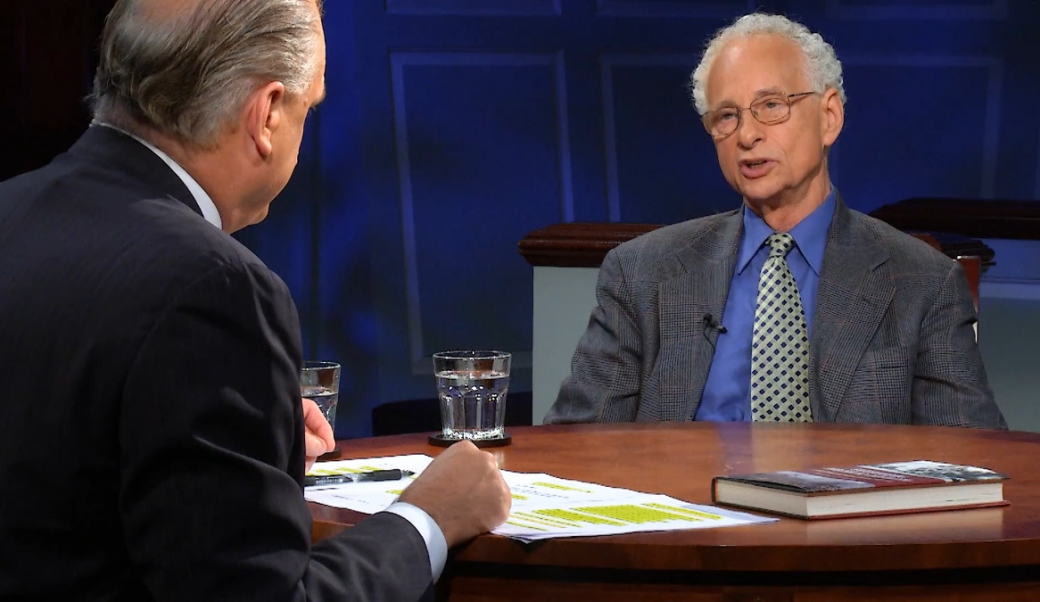

Eric Liu

This week on American Forum we talk to Citizenship University Founder and CEO Eric Liu, who spends his time thinking and writing about how citizens can best be engaged in democracy—and encouraging Americans to join in the governance of our society. Over 2.5 million people have viewed his Ted Talks online. Liu was a speechwriter and policy advisor for President Clinton, and he is also executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Citizenship and American Identity Program. His books include two bestsellers, The Gardens of Democracy and The True Patriot. His latest work is You’re More Powerful Than You Think: A Citizen’s Guide to Making Change Happen.

Governance

Is citizenship dead?

Transcript

Douglas Blackmon (set over shoulder): This week on American Forum, we look at what it means to be a constructive citizen in these troubled times.

OPENING TITLES AND MUSIC

0:48 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. We spend a lot of time on this program talking about the importance of civil discourse and active citizenship. Amid all the partisan rancor in recent years, that has felt more important than ever, but often almost impossible to find—whether on cable news, on the floor of Congress, or, maybe most importantly, at the family dinner table. Some believe the ascendancy to the White House of Donald Trump is proof that civic involvement is flourishing—either in how his campaign stirred engagement by supporters who hadn’t been part of the process before, or now motivating millions of opponents to resist him. Others say the Trump presidency is causing many Americans to just flee any involvement in debate at all. No matter what, the issue of citizenship and our obligations as patriots has never been more prominent in American life. This week, we’ve invited a guest who spends his time thinking and writing about how citizens can best be engaged in democracy—and encouraging Americans to act—to become players in the governance of our society. Over two and a half million people have clicked on Eric Liu’s Ted Talks online. He was a speechwriter and policy advisor for President Clinton. He is also the founder and CEO of Citizen University, and also executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Citizenship and American Identity Program. We’ll learn more about all of that in a few minutes. His books include the bestsellers The Gardens of Democracy and The True Patriot. His newest book is titled You’re More Powerful Than You Think: A Citizen’s Guide to Making Change Happen. Eric Liu, thanks for joining us.

Eric Liu: It’s great to be here.

2:19 Blackmon: It’s good to have you back. The last time you were here, uh, we were having a—it was almost three years ago, I think, uh, and we had a debate about political polarization, I think. And you were one of the debaters in that process. And in the course of that, you met for the first time, I think, a leading Tea Party activist who was on the other side of the debate, uh, along with George Will, and you guys have developed a friendship. And, from looking at what you’ve been up to lately, you seem to do stuff with the Tea Party guy all the time now.

Liu: Oh, we sure have, Matt Kibbe. Matt and I met here at that debate, and, uh, over the years what we’ve come to see is that even though his policy views and preferences are different from mine, we share this abiding interest in bottom-up citizen power right now. His work starting with the Tea Party and now with an organization called Free the People is in many ways a mirror image of what we’ve been doing at Citizen University, and so we’ve gotten a lot of chance to play together thanks to you.

FACTOID: For additional information, log on to freethepeople.org

3:17 Blackmon: Well, that’s good. So, at least in one case, we’ve overcome partisan difficulties through what we do—

Liu: That’s right. That’s right.

Blackmon: —at American Forum. But—but tell us more about what you’re talking about. I mean, I’m an old journalist guy, worked in newspapers a lot of the time. I can be—uh, I care about these things. I believe in these things, but I’m also kind of skeptical and cynical about, uh, human—the human spirit and do-gooders like you. (laughter) So what are we really talking about here? What is Citizen University? Just map out for us what you are really pushing people to do.

Liu: I love that you confess to your skepticism about the human spirit. Um, Citizen University, we exist to democratize understanding of how power works in civic life. All of our work, whether with folks on the left or the right, in different sectors of civic work from immigrant rights, to veterans, to voting reform, to national service, to civic technology, um, is really about this fundamental question of how do you show up as a pro-social contributor to community?

FACTOID: For additional information, log on to citizenuniversity.us

And I think the reality is that even before this most recent election cycle, um, we’ve been in a multi-decade cycle of decline in this country where people have forgotten the values, the systems knowledge, and just the hard skills of how to show up in civic life. And so our organization has existed to help spark the revival, uh, of that practice and that culture. I’m not a Pollyanna. I have no pretense that our work alone is going to lead to a national sea change in attitudes. But I do believe that at every time in American history where there’s been a period of renewal and awakening, it has happened because a catalytic minority of people decided, “We’re not going to take this anymore. We’ve got to be part of the solution. We’ve got to be part of the healing of the body politic.” And the work that we do at Citizen University, pulling together folks from across the political spectrum who are interested in this revitalization of citizen power, says to me that we are in that kind of period, uh, of awakening and renewal right now.

5:24 Blackmon: But it seems that today we have this surge of activism you’re describing, but it’s all across the political spectrum. Uh, it’s hard to maintain or sort out who really is right about, uh, capital gains taxes, and that might be a motivating factor, or the morality is complicated on things like abortion. Even if—even if you think you have a clear view on that, it’s complicated, so how do you—in that sort of environment where it’s so much harder to know really what is the right thing, uh, how do you motivate people across that spectrum, or can you? Do you have to sort of work with one set of folks?

Liu: You know, I think there are two things to—to unpack here. In the first place, just to go back to that, I think, natural and in many ways beneficial spirit of initial skepticism, um, nowhere do you see that kind of skepticism or cynicism more sharply than around the very topic that I’ve centered this new book on, which is power. Right, for most people, the very word “power,” the very topic of power, is a dirty word. It seems like the kind of thing that, um, “Oh, this is going to be sordid. This is going to be a real House of Cards kind of Game of Thrones sort of discussion.” And every association with have with the word and the idea of power is essentially a negative one: power trip, power hungry, power mad, right? My view is that power is—in civic life is simply like fire. It just is. It’s not inherently good or evil. And just as with fire, the mere fact that it can be put to evil uses does not absolve us of the responsibility of figuring out how to put it to good uses, right? Uh, and in the case of civic power, becoming literate in understanding how—and I define it simply as a capacity to ensure that others will do as you would like them to do. Now, again, to some people that sounds kind of menacing or threatening—

7:18 Blackmon: Machiavellian. Yeah. Right.

Liu: —or Machiavellian or maybe Tony Soprano, like, you know, “It’d be a shame if you didn’t do what I wanted you to do,” right? Um, but in fact let’s be honest about every single relationship we’re in in our lives.

FACTOID: Machiavelli’s the Prince was guide to political power and intrigue

With our families, with our neighbors, with our coworkers, much less with fellow citizens. We’re always thinking about how to get other people to do what we want them to do, right? This is the nature of human life, and so I don’t think skepticism is a bad thing. I think it’s just being grownups about naming this dynamic and then thinking about how do you harness this dynamic toward a greater sense of the common good, which goes to the heart of your question here, because who gets to define the common good, right?

Blackmon: Right.

Liu: It is true that, um, in politics today perhaps we lack a single fight that has the unifying moral clarity of certainly, abolition a century and a half ago, or even to a certain extent desegregation and—and racial integration. Although it is worth remembering as we sit here in Virginia, um, that to plenty of folks 50, 60, 70 years ago it was not as morally clear as it seems today in hindsight. There were a lot of folks who were quite comfortable with that status quo, and that status quo seemed like a natural order of things. And it took, again, a catalytic, motivated minority to begin the—to change the frame of the possible. But put that to the side. Today, I think, what unites so many of these surging civic movements, whether it is the Tea Party or Occupy Wall Street or 15 Dollars Now or Black Lives Matter, whatever it is, is this sense that we’ve been living through four decades plus of a concentration and monopolization of power, wealth, and voice in this country.

FACTOID: Tea Party triggered in 2009 by Bush recession, Obama policies

And to folks on the left and the right, that has been not only offensive; it’s been an abomination. It has been a betrayal of the American idea, and people across the political spectrum see different causes for that, and have different things they want to focus on. To folks on the right, they see a concentration of power in the hands of the federal government. To people on the left, they see a concentration of power in the hands of multinational corporations, uh, and in many ways they’re both right.

19:19 Blackmon: We’re also in a cycle in our politics that President Trump is the fourth consecutive president in which we’ve had very active public discussion of the idea that this person should be impeached, uh, beginning relatively soon after they became president. Uh, in the case of Bill Clinton, we, in fact, did impeach him over something that, when you look back on it with the distance of time, is a—was a very serious and terrible thing to do, particularly the misleading of the American people about his personal, uh—his personal moral failures, uh, and doing it under oath, but we had another president who initiated a war that cost many lives, that turned out to be, uh, on a messy set of ideas.

FACTOID: Bill Clinton impeached in 1998, acquitted by U.S. Senate in 1999

Okay, at least that’s a substantive thing to have a discussion about whether this president was a terrible failure, but then we have a president who wins a great mandate, uh, and there’s immediate, uh, discussion of—by his opponents that he should be impeached rather than just defeated. And now, we’re into—we have another highly controversial president who—there may be many things about him that many people don’t like, but there hasn’t been anything to surface that in any fashion would suggest a substantive basis for the impeachment of this person who has barely even been inaugurated. And yet, among these disparate organizations, uh, there’s a sense that if we lost at this one moment we will, by whatever means necessary, seek to get that power back. It seems to me that there’s a baked-in destructive dimension to these very things that, in another way, seem very constructive. But so, how do you deal with that? How do you balance that the very good thing you’re after also leads to hysterically ridiculous demands by the very same people at times?

Liu: Well, I think one of the—the impeachment cycle that you’re describing is specifically a feature of what’s been going on in Washington, D.C. I'm not even sure—when you described this as our national politics, I'm not quite sure I want to even give D.C. that much credit. This is not our national politics. This is the dysfunction of a group of leaders currently in office, in the Beltway, who have begun to betray norms of democratic self-government and be—begun to betray norms of recognizing that democracy is a game of infinite repeat play. That you can’t just scorch the earth and impeach your way to ultimate permanent victory, that it requires some kind of give and take, right? And those norms have corroded and eroded over the last 25, 30 years, um, you know, I would say, but it wouldn’t just be me. I mean, I think political scientists Norm Ornstein and Tom Mann have written a great deal about the ways in which the polarization of that D.C. politics, um, has been quite asymmetrical, uh, driven more by the ways in which the right has gone off the deep end, um, than by the polar—the extremism of the left. But again, put that to the side.

FACTOID: Book by Mann, Ornstein titled: It’s Even Worse Than It Looks

I think that what’s going on outside of the Beltway and outside of the federal institutions, uh, of national government, um, is this incredible surge not only of citizen activism, but of renewal.

12:32 Blackmon: And yet there is some tendency that, uh—that rather cynical things also can turn out to happen. How do we—how do you keep that from happening? How do you have these blossomings of—of human spirit and—

Liu: You don’t. You don’t keep that from happening. I mean, this is human nature, and this is where I would agree fully with you. I mean, uh, let’s go back to a son of Virginia.

FACTOID: Founder Madison warned against political factions in Federalist #10

I mean, the way that Madison wrote in the Federalist Papers about the—about the nature of action, faction exists because human preferences, human differences in aspiration, human competitiveness is a constant, um, and, you know, you’re not going to wish away a faction, and God forbid we ever try to do away with faction, um, in some top-down fashion. The reality is that in all human endeavors, all human endeavors, Little League team, multinational corporation, um, there are going to be those interpersonal politics. There are going to be those power struggles, uh, for who gets more—more playing time, who gets more airtime, who gets more face time. That is the nature of us as status-conscious competitive beings, right? So I—when I talk about the promise of this blossoming moment that we’re in of bottom-up citizen power, I’m not saying in any kind of way, um, that that side of things is going to disappear. Every movement that, um, you can point to in American history that you might be proud of—suffrage, abolition, the Civil Rights movement, marriage equality—um, all of these that we look back on history and may have a tendency to, uh, neaten them up and button them up kind of nicely and draw them in an arc of, uh, continuous progress, um, they are completely messy affairs, uh, and they are made messy not only by competing agendas, but they’re made messy, uh, my often bitter personal rivalries and often bitter, um, you know, human frailties, right? Um, that’s the nature of the game. I’m not saying that goes away, but I am saying that, um, you know, the—all that a democracy guarantees us is the opportunity to bring to bear our fullest human aspirations together in ways that sometimes can transcend those human frailties, right? Um, whether we actually take advantage of that opportunity is simply a matter of whether we remember to stop giving away, throwing away the inherent power that we have as citizens, right? And I think this is why I am net-optimistic about our moment. You alluded to it in your introduction. Um, you know, I actually—I am no fan of Donald Trump, uh, and his presidency, but, uh, I will give him plenty of credit whether or not he wants it, um, for single-handedly—he alone has sparked the greatest surge in civic engagement in this country in half a century. Um, he’s responsible for this unbelievable surge of participation, knowledge, renewal, activism, and that’s not just on the left among people who are resisting him. It’s among libertarians, um, who are equally concerned about his tendency to overreach in using executive power. It’s among reform conservatives who are concerned, um, that with Trump defining the brand of conservatism that the ideas that they’ve been focused on and trying to advance, uh, might be getting corroded. Uh, it’s—it’s among plenty of folks across the political spectrum, and indeed, as you said at the outset, it’s among the folks who brought him to office.

15:57 Blackmon: And the difference between what you’re talking about and a pol—a particular political ideology is that you’re not suggesting that there is a garden of Eden, that there is some state of perfection that—and if we could just figure out what is the—the state of perfection, uh, and get to it that everything would be taken care of and we’d have a static, perfect America. Uh, that place doesn’t exist. We maybe can fantasize about it, but we can’t get to that, but that, instead, there is this—this endless struggle of these various forces. Uh, the key is constructing some boundaries, perhaps, and a set of rules and expectations, the most basic of which is that—I think—that it’s OK for the other guy to win sometimes, uh, and you have to accept that you lost this game, uh, and come—and be willing to play the game again another time, a game in a substantive way. And—and in way, I mean, that is some of what you write about in the book, sort of set of—a set of principles to how these things should happen, a set of things that Americans should know and understand.

Liu: You know, I think that—I absolutely agree that there is no Eden or utopia for us to be striving toward, and I’m, uh, quite cautious or even wary of anybody who starts promising utopia. I’m—I’m just belatedly in my career as a reader reading Edmund Wilson’s book To the Finland Station, uh, which is this doorstop of a history of, um—of the revolutionary idea that had its seed in the French Revolution and plays out all the way through, um, the Russian Revolution and the rise of communism there.

FACTOID: Wilson’s To the Finland Station was first published in 1940

And it’s essentially, if you have to boil down the 800 pages of that book, uh, a great warning to humans, uh, about the dangers of a utopian revolutionary instinct. Um, the thing that is great about the American revolutionary instinct, um, is that our founders and framers were deeply, deeply grounded in a realistic notion of human nature, right?

FACTOID: Wilson wrote for Vanity Fair, New Republic, New Yorker

17:52 Blackmon: And a fear of the mob.

Liu: And a fear of the mob, but also a—a believe that, um, it—it was precisely going to be, um, you know, the self-interestedness of Americans that could be actually put to positive use if you designed a government a certain way, right? That said, one of the core principles that I lay out in this book here that I think is really important for us to evolve towards—it’s not chasing a utopia, but it is a matter of evolution—you know, while self-interest is a human constant and people will always be self-interested, how we define self-interest changes over time, right? I think this is a critical point. Several hundred years ago, people defined their, you know—serfs defined their self-interest only in terms of what would make their noblemen happy or good, right? And the Enlightenment changed that, right?

FACTOID: Enlightenment gave rise to modern ideas of human freedom, equality

People before the Enlightenment also defined self-interest in terms that were ecclesiastical, um, but the Enlightenment, the Renaissance, and that period of time shifted people’s notions of self-interest, uh, into something closer to what we have today, right? And I think we’re living through this time right now where we begin to realize it is unavoidable as a matter of science to see the ways in which our fates are so bound together and woven together, right? You think about climate change. You think about obesity. You think about opioid use. You think about any social phenomenon or physical phenomenon in the world, and you realize we are imbedded in a network, in a complex adaptive system in which is truly can be said now that there is no such thing as someone else’s problem. You can put your head in the sand for a while, but eventually that other person’s problem is going to infect you. It is going to hit a node that is close to you, and that node is going to spread a contagion to you.

19:37 Blackmon: Anybody who watches this program with any regularity has heard me make reference to—to my cousin Ricky on Blackmon Road, uh, in DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, and Ricky is a real person, and I love him very much. Uh, and I don’t know if he’s ever seen this show, but the, uh—but I descend from these folks on all sides. I descend from people who, uh, uh, have very simple lives, deep, deep, profound poverty, and so I come from these folks, and it is true that, uh—that the Trump campaign, uh, you know—that there were people who had never shown any kind of activism, uh, completely disengaged with civic life as far as I know, very engaged in church life but completely disengaged from this kind of civic life, uh, became a part of the phenomenon, and, uh—and my cousin Ricky the loudest of them. And the—and on the one hand, we disagreed about some things, not so much about Trump himself but things related to all that, but—and some of it was hard, you know, some of these really, as you described, complicated conversations. But one thing I became very aware of was that part of what they were reacting to was a generation of—of popular culture and public affairs commentary and people who look a lot like I look now, um, essentially saying, “There’s something wrong with you. And a big part of what bubbled up was that Donald Trump did—that candidacy did allow that constituency of people to express that they were tired of all that, uh, and the—and I think that is a good thing. That is a—even—whatever decisions they make on particular things, that’s a good thing, and maybe that’s the beginning of a much more constructive kind of engagement in civic life.

Liu: Well, here, now, I’m going to criticize—now, I’m going to be the skeptic, because I—I actually think—yes, um, I think there can be some good there, but I think it is important for us to be eyes wide open about the—about the complicated nature of the support that a lot of people have shown for—for President Trump. Look, as I write in this book, we’re living through this period that is not just an age of bottom-up—bottom-up citizen power. We’re living through this age right now where, um, simultaneously we’ve had these four or five decades of, um, radical, severe inequality and concentration of wealth and also concentration of voice in our politics, right, and in our media, and that’s part of what cousin—Cousin Ricky, you know, is—is feeling, the sense that, um, he—he is truly an outsider, he is truly not of the nation, um, that is getting to tell itself a story of what this nation is becoming. At the same time, there’s another tectonic shift going on in the United States, which is that fundamentally Americanness and whiteness are delinking. That’s a big one.

22:21 Blackmon: And that’s a good thing, I think, you’re saying.

Liu: Well, I happen to think it’s a good thing, but I think—but I acknowledge fully that it is—it is freaking a lot of people out, right? Um, you know, we are within sight of the year 2040, um, when demographers tell us that we will become a majority people of color country, right?

FACTOID: U.S. non-Hispanic whites dropped from 76% in 1990 to 63% today

I guarantee you in the year 2040 the people who run universities, who run the media, who run the Fortune 500, who run Hollywood will not be majority people of color, right? The power structure in this country will still lag that demographic shift. And yet, for plenty of folks like Cousin Ricky, all they’re seeing is the ways in which all around them this message of, “America is diversifying; America is changing,” and whatever dignity and worth that you might have even unconsciously put into the fact that, whatever else I’ve got or whatever else I don’t have, I’ve got whiteness, um, that the value of that is declining is a thing that is freaking plenty of people out, right? And I think we have to—so what do we do with that? I think part of what it means to be a powerful, engaged citizen right now—and I keep using the phrase “grownup” so be a grownup citizen—is to name that and to face that, right, to name it and just be really pl—plain and clear about, “This is a reality, and let’s talk about what you’re scared of. Let’s talk about what you as a white person are scared of. Let’s talk about what me, as a nonwhite person, am scared of. Let’s talk about the ways in which all of these anxieties when they go unspoken feed a lot of pathologies in our politics.” Right? But if we can begin to name them, um, I mean, they’re not going to be cured, but we can actually at least create a different foundation, uh, on which to understand each other, and we can begin to recognize that, look, if Americanness is not going to be centered on a default setting of whiteness or white maleness—and that essentially was a big part of the Trump promise, right, that, you know, to make America great again is very much about kind of a restoration of a time and an identity and a self-story in which whiteness was at the center. Um, if we’re not in fact going to be there anymore, where can we be together? Is there a place we can go together that’s not just about, “Oh, well, now I’m the nonwhite guy. I’m going to lord it over you, and I'm going to punish you,” right, but rather what else—what new fate can we create together? I’m interested in saying to them, “I get that you’re scared. I’m scared, too, but be a grownup. Join me in this conversation about what we’re going to do together

24:52 Blackmon: Thanks for being here.

Liu: Doug, thank you for having me.

Blackmon: We encourage you to think about and act on the ideas discussed here today however you see them fitting your life and wherever you are in America whether that is in DeSoto Parish, Louisiana or Jackson Parish. The one thing that truly does make America great, is an informed and active citizenry, no matter what side of the political fence you’re on. We hope part of how you engage in citizenship will be to keep watching future editions of American Forum, where we are always discussing these issues, our president and the most urgent questions facing our leaders and our society. You can watch us on your local PBS affiliate. Or to jump into our ongoing dialogue, look for the Miller Center Facebook page, visit our new, revamped website at MillerCenter.org, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @douglasblackmon. Eric Liu is @ericpliu. See you next week.