Americanization

In mid-1965, Lyndon Johnson decided to substantially increase US ground troops in Vietnam

General William Westmoreland was, in the words of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, "the best we've got." And he was determined to succeed in Vietnam. Westmoreland had been in South Vietnam since early 1964 and had commanded the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) since June 20 of that year. He'd watched as efforts to help stabilize the country had failed.

Under President Kennedy, the United States had sent military advisors and equipment to assist the Army of South Vietnam (ARVN) in defeating Communist guerillas of the National Liberation Front. The guerrillas called themselves the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF), but South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem referred to them pejoratively as the Viet Cong, or VC, a contraction of “Communist Traitor to Vietnam.”

US forces became even more directly involved in military operations against the Vietnamese Communists—in both the North and South—following the August 1964 naval encounter in the Tonkin Gulf, which prompted President Lyndon Johnson to launch air strikes on North Vietnam. Following Johnson’s election as president that November, and attacks on US bases in South Vietnam the following February, LBJ sent in Marines to provide base defense.

Neither these reinforcements nor the inducement of economic aid lessened the tempo of the war, however, and by June 1965, as Westmoreland closed in on the one-year anniversary of command, roughly 40,000 US Marines were in country, protecting US air bases and conducting limited offensive operations to secure them.

But the Communists still seemed to be winning. Increasing numbers of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regulars were moving down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the South. The PLAF were getting stronger. The country was falling apart. Westmoreland needed to do more.

“I see no course of action open to us,” said the commander in a June 7, 1965, telegram, “except to reinforce our efforts in SVN [South Vietnam] with additional US or third-country forces as rapidly as is practical. . . .”

Westmoreland asked for 150,000 soldiers but also requested plans to “deploy even greater forces, if and when required, to attain our objectives or counter enemy initiatives.”

“I am convinced,” he said, “that US troops with their energy, mobility, and firepower can successfully take the fight to the VC.”

A restless and troubled President Johnson called Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield the next day to discuss a troop increase. Looking into the future in Southeast Asia, Johnson could envision a never-ending commitment. "Where do you stop?" asked Mansfield. "You don't," replied Johnson. (The following call has been edited for clarity.)

[Full transcript]

DELIBERATION AND DECISION

Johnson struggled with the decision, but in a sense, he had already made up his mind. He started his presidency declaring, “I am not going to lose Vietnam," and he had slowly increased his commitment to keeping South Vietnam from falling to Communism.

Still, this latest request represented a major commitment: Instead of helping the South Vietnamese win the war, American soldiers would be shouldering much of the burden themselves. In a series of phone calls in June and early July with Robert McNamara, his secretary of defense, Johnson expressed deepening concern about US prospects in Vietnam but seemed to convince himself that he really had no other choice but to grant Westmoreland's request. (The following calls have been edited for clarity.)

[Full transcript]

[Full transcript]

[Full transcript]

[Full transcript]

[Full transcript]

THE COST OF VICTORY

Most of Johnson’s advisors wanted to support Westmoreland and give him both the soldiers and freedom he needed to succeed. So did former president Dwight Eisenhower. (See sidebar at right for more details.) The lone dissenter among those closest to the president was Undersecretary of State George W. Ball. In a memorandum, Ball asked a fundamental question: Was success in Vietnam truly worth the tremendous cost the United States might be forced to pay?

Once the United States started to suffer significant casualties, Ball said, “Our involvement will be so great that we cannot—without national humiliation—stop short of achieving our complete objectives. Of the two possibilities I think humiliation would be more likely than the achievement of our objectives—even after we had paid terrible costs.”

Ball’s argument failed to move Johnson, who was more concerned with several factors—personal, political, and geopolitical—that he believed demanded a larger commitment of troops. By the end of July, the president had decided: 100,000 additional American GIs would head to Vietnam.

GOING IN

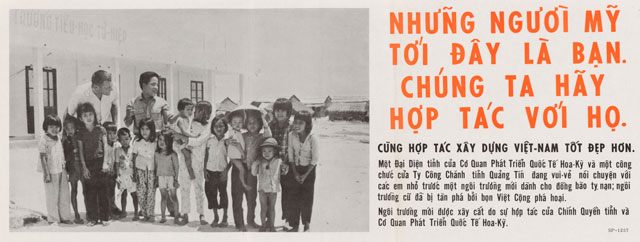

Johnson knew that "winning" in Vietnam would be hard. But he believed that the massive firepower of the American military would be enough to pressure North Vietnam into negotiating its withdrawal from South Vietnam and ending its support of the NLF. And he believed that the best-trained, best-equipped army in the world could overpower North Vietnamese and PLAF soldiers in the field and buy time for Saigon to establish a functioning civil society. South Vietnam would thus be preserved, and the dominoes would stop falling.

Johnson was reluctant to gin up public support for a massive deployment. It was a conscious decision on his part, designed to maintain momentum for his Great Society at home and to lessen the energy for greater Soviet and Chinese involvement in the war. Instead, he would slowly ratchet up the pressure on North Vietnam to minimize American casualties while pushing Hanoi to the breaking point—the proverbial “crossover point,” when the loss of Communist soldiers outpaced the ability of Hanoi and the PLAF to replace them.

At his first press conference announcing additional troops, on July 28, 1965, Johnson revealed an increase of only 50,000, even though there were plans to give Westmoreland another 50,000 in 1965 and a further 100,000 in 1966. The bombing runs also increased apace, with the number of sorties and targets growing with each passing month.

Ironically, this strategy of slowly increasing pressure on the North was also intensifying pressure on America, perhaps pushing LBJ's own country to the breaking point in a war that had never been formally declared. Even as US soldiers were killing off enemy troops and even though US bombers were targeting North Vietnam's capacity to wage war, the North was increasing its commitment to more than keep pace—and receiving help from China and the Soviet Union to do so. More North Vietnamese troops made their way south. More Americans were dying. More US pilots were becoming prisoners of war.

As Hanoi ratcheted up its effort, Saigon appeared to be having little success. South Vietnamese officials, many autocratic and corrupt, were unable to inspire sufficient loyalty toward the government. Their image as puppets of the United States continued to mitigate Saigon’s appeal. Political unrest continued to roil the cities, leading the GVN to battle its nominal supporters while also taking on the Communists.

American troops on search-and-destroy missions in the countryside—without numbers sufficient to capture and hold territory—sowed chaos as they tried to ferret out PLAF guerillas and NVA troops. Having struggled with a long history of colonial occupation, many in South Vietnam were suspicious of western soldiers. And much as they might fear the Communists, the destruction of their homes and the violence in their villages was more palpable and indiscriminate.

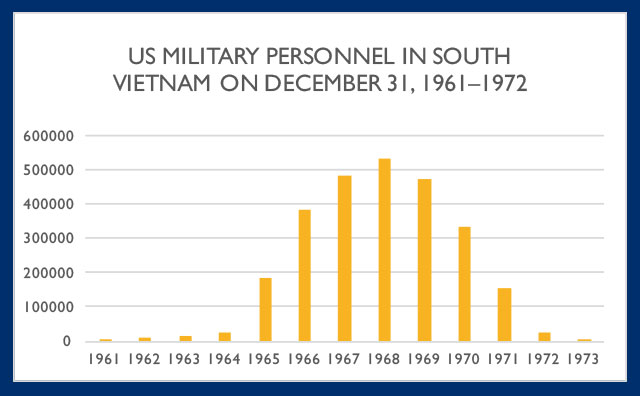

The military stalemate—and destruction—continued as troop numbers rose. Official "body count" reports (the number of Communist troops killed) convinced Westmoreland that he was slowly defeating the enemy, difficult though it was. By mid 1967 nearly 450,000 Americans were in Vietnam, and the commander wanted another 200,000 over the course of at least two more years.

Economic aid to help build the South Vietnamese economy reached $625 million, a quarter of all US aid disbursed in 1967 worldwide. Elections held that September were designed to create the veneer of representative government, but the installation of generals Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and Nguyen Cao Ky as its heads offered little respite from charges of cronyism, graft, and authoritarian rule. By then, roughly 25 percent of South Vietnamese citizens, by some estimates, had been driven from their native villages.

As 1967 drew to a close, Johnson resolved to stay the course. And he sought to keep the public right there with him, even as a plurality of Americans now regarded the commitment of US troops to Vietnam as a mistake. Mounting a “progress offensive” to reverse popular sentiment, LBJ and key officials maintained that there was indeed light at the end of the tunnel—that the war, as Westmoreland had said in late November, "had reached a point where the end begins to come into view."

Events early in the new year, 1968, would test that assessment, as well as the patience and support of the American public. Within three months, the country, the war, and Johnson's political fortunes, would begin moving in different directions.