Transcript

June 11, 2013

Riley

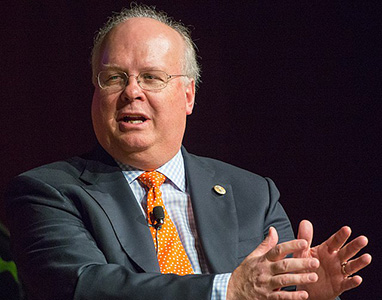

This is the Karl Rove interview as a part of the George W. Bush Oral History Project. I have already conveyed to Karl Governor [Gerald] Baliles’s greetings and gratitude. I don’t think it’s widely known, but Karl was an important advocate with the Bush Foundation on our behalf here. As you know, that foundation has just extended a certificate through the end of the project. We’re grateful for that.

You know the basic ground rules for the interview, right?

Rove

Yes.

Riley

We’re going to make a transcript of this interview. Everything is done under a strict veil of confidentiality. You look at the transcript, you control the release, and you control the contents of the interview. I’m pleased to say that we’ve got an unblemished record in maintaining confidences since the Gerald Ford administration.

Rove

Very good.

Riley

Now, when Katrina [Kuhn] 1st told me we had this time, my first inclination was to think, Great, we can start on his biography and deal with that and then work our way on to the Presidential years. I had only read bits and pieces of your memoir up until that point. Now I’ve read it and you’ve already done that.

Rove

I can skip over it.

Riley

Exactly. Well, I don’t want to skip over it entirely.

Rove

That’s the only part of the book that I had no intention of writing.

Riley

Is that right?

Rove

Yes, indeed. I got to the tail end of it and my editor—

Milkis

Your editor made you do it.

Rove

She said, “You know what? You can’t show up at the age of 22 meeting Bush.”

Perry

That’s a good editor.

Rove

So you have to write the first three chapters. Then she said, “I’ve made a helpful list of all the ugly things people have said about your childhood and your parents, so here they are. You’ve got to write about what a Rovian campaign is, chapter four.” Otherwise, I would have started with chapter five.

Riley

It was terrific and, again, unexpected.

Milkis

I really liked it.

Riley

We see bits and pieces of the memoir show up in briefing materials for other interviews, but it was the first time I’ve had a chance to sit down and start from the beginning, so it was very helpful. I’m glad you mentioned a Rovian campaign though, because that’s actually where I thought it would be useful for us to start. You outline eight hallmarks of the Rovian campaign, but we don’t really hear how you reached those conclusions. I’m assuming that, because it appears here in a book, you must have defined these things before you got to Presidential politics.

Rove

Right.

Riley

Can we start there, beginning with “the campaign must be centered on big ideas that reflect the candidate’s philosophy”? Partly, how do you come by this? And it’s also a way of my asking about your own conservatism. You talk a lot about how you become interested in politics, but a little bit less about your own political philosophy and how you develop that, so let me throw out those general things. This is very informal and conversational, so I hope you’ll let us treat it that way.

Rove

You bet.

Riley

Thanks.

Rove

The big ideas came from the experience of being involved in campaigns over the years. I saw a tendency for people who didn’t really have a clear idea of why they wanted to be what they were seeking, to come up short. For example, Clayton [Claytie] Williams in 1990; it was really never clear what he wanted to do, except he didn’t like Ann Richards. Another case was my close friend, Kay Hutchison, when she ran for Governor in 2010. Particularly in my early involvement, it struck me that people who had a bigger idea about what they wanted to be—even more of an idea about what they wanted to do than what they wanted to be—had a greater chance at success. The people who had less of an idea about what it was they were running for—I want to be that as opposed to do this—tended to come up short, more often than not.

Perry

How did you help people develop that?

Rove

Well, my view is that the higher the office, the more a campaign is akin to The Emperor’s New Clothes, and people will see you as you are. So I would tell candidates or prospective candidates, “Take a yellow pad, find a quiet day, and write down why it is you want to do this job.” They need to get at what it is that they want to achieve, what it is that they want to do, and what it is they want to focus on, because at the end of the day, you can only give people so much. It’s got to really come from them.

It’s like Bush in ’93 and ’94. One of the most impressive things about him as he got ready to run for Governor was that he had a fully formed idea of what he wanted most of his big priorities to be, and he had not only thought about them, but they were ingrained in him and he felt passionately about them. A couple of them were at the top of people’s agenda. Education was at the top of the agenda, and he’d given it plenty of thought over a number of years and had come to the conclusion that certain things needed to be done. We were in the midst of a big battle over school finance, which our then Governor had absented herself from. Bush knew he would have to deal with the school finance issue, but he also thought that it was obscuring what was a bigger issue, which was accountability. How do you measure for results and insist that the system serve the needs of every child? We were over here talking about property tax rates and poor districts and wealthy districts and transfers and so forth, and he said, “We’ve got to resolve that, but we’ve got to resolve the bigger issue.” He’d thought about it for a long period of time; he’d educated himself on it.

Even more interesting was his focus on juvenile justice, because he’d been involved in a series of juvenile justice programs over a number of years. He had developed a friendship with a district court judge who specialized in juvenile issues and they would meet for coffee every couple of months to talk about the issue. It was not at the top of people’s agenda, but he wanted to make the campaign in part about that. Welfare reform was the third issue. Again, since he was a young man, he had been involved in trying to confront poverty through mediating structures, through citizen-, faith-, and community-based groups, and he had thought about this a lot.

What was so impressive about this was that he came with a pretty good idea about what he wanted to make the campaign about. What he wanted help on was framing it, phrasing it, and finding the right language. The only thing he added on to his agenda—We had a big problem with trial lawyers and civil litigation, and I suggested that we do this as an outreach to small business, and of course it fit with his world view. Successful candidates like that impress upon you the good things, and losing candidates tend to impress upon you the bad things, and that’s where the big ideas came from.

Perry

Can we go back to the world view, because it seems that would correspond mostly with the big idea?

Rove

Right.

Perry

You’ve named off these three or four areas that are policy areas that the soon-to-be Governor thought carefully about, thought a long time about, and you said fit with the world view. How did you see his world view at that time?

Rove

First of all, it was different. Most Republicans, when they talk about welfare, talk about it in terms of freeloaders. We had a great United States Senator, Phil Gramm, whose campaigns I was involved in, and Phil talked about welfare from the perspective of, we’ve got people riding in the wagon and people pulling the wagon, and there are too many people in the wagon and not enough pulling the wagon.

Bush talked about it very differently. He talked about how dependency on government saps the soul and drains the spirit of our very best. He talked about welfare as a system that kept people from achieving all that they could be in life. This was a much more optimistic and inclusive and unifying view than saying the problem is we’ve got too many people who are freeloading on you and me. I thought it was a very interesting approach.

The same on education, where his concern—Most Republicans who run for office and emphasize education are far more concerned about, or at least used to be far more concerned about, what was happening in affluent white suburban districts from which they came. Bush’s attitude was that the system is failing, and it’s failing you if you’re black, if you speak Spanish at home, and you’re poor. In fact, he came up with the idea that we have a system that’s leaving children behind, from which the label No Child Left Behind came. The idea of accountability, holding the system responsible for results, comes from it failing too many people and, as a society, we couldn’t afford that; it was a conservative but compellingly compassionate view of how life ought to be.

He’s not an angry guy and he doesn’t—A lot of politicians manage by anger, and he never has. I remember the time I saw him more angry than any other time before he became President, and that was when he went to East Texas and was selling his education reforms. Some middle-aged, white teacher in a clearly African American–dominated East Texas school said, “Well, Governor, you just have to understand, some of these kids just can’t learn.” And he knew exactly what that was, which was a code word for, “I’ve got a lot of black kids; don’t expect me to get them to read.”

The same thing goes for juvenile justice reform. If you talk about crime and you’re Republican, you’re a hard-ass most of the time. You know, throw the little buggers in jail and to hell with them. Instead, he said, “We’re at risk of losing a generation of young people and we can’t afford, as a compassionate society, to do that. We have to reform the system, give them tough love. They have to have penalties; they have to be held responsible for their actions. By doing so, we’ll help them come to a life that is one of success and opportunity.” So it was much different rhetoric.

Milkis

It seemed to me, in reading your rhetoric, Karl, that you had a deep interest in these kinds of ideas before you really get to the campaign. You apparently had been reading a number of books about this kind of world view, and you passed some of those books on to President Bush.

Rove

Right.

Milkis

And that’s part of the framing.

Rove

Right, a lasting view.

Milkis

I get a sense from your memoir that you were thinking about the Republican Party and its path, and that it needed to undergo some changes. You even mention the party of [Abraham] Lincoln, that we have to get back.

Rove

Right.

Milkis

I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but this is something you had given a lot of thought to.

Rove

Yes, it was.

Milkis

It’s like, this is my candidate.

Rove

I started my consulting business in ’81, mostly as a direct-mail guy, but by ’84 I became a consultant as well. I’m doing the direct mail, but I’m also helping shape the strategy. So you do find a lot of candidates who say, “What should this be about? Please help me.”

Milkis

It sounds like a dissertation. What am I going to write my dissertation on?

Rove

Yes. You’re simultaneously trying to pry it out of them and hopefully helping them along. I was trying to figure it out and trying to pay attention. I didn’t get involved in politics because it was like a game or because it was like a family business. I came to it because I was concerned about ideas, so it did give me a chance to educate myself and then help educate my clients. The more you had to educate them, the slower they were to grasp it, the more dangerous a candidate they were. I really liked the people who were trying to sop it up and were already thinking that they needed to figure out a way to talk about this that is more compelling, and had given it some thought themselves.

Riley

Well, Karl, tell us a little bit more about your own intellectual journey. It’s clear from the book that you’re conservative, that you’re conservative from early on, but why are you conservative? What is it, which idea is it if you’re in politics? What flavor of conservatism is it that you’re finding most appealing, and which flavors are you finding less appealing?

Rove

Look, I grew up in the West. I really don’t know where my philosophical beliefs come from. They certainly are not handed down directly by my parents. As I say in the book, my dad never told me who he voted for until he was in his 70s. I mean, he was one of these reticent, Midwestern Scandinavians who just felt it was none of your business. And my mother was completely illogical, she was completely insane.

I think part of it has to be that I grew up in the West. I grew up in small towns in the Rocky Mountains in the ’50s and ’60s, and there was a Western individualism there that’s congenial to Republicans, just as it was, incidentally, congenial to being a Democrat in the 1860s and 1870s. I think every young teenage conservative goes through being semilibertarian, and it just so happened that Milton Friedman was writing and having an enormous influence then, and his books were available in cheap editions. I’ve always been a voracious reader—something that my father encouraged—and I was reading all these kind of weird books when I was very young. I put it in the book and it’s not a joke: I literally wrote my fifth-grade civics paper on the theory of dialectical materialism.

Riley

That one didn’t stick though.

Milkis

And that turned you into a conservative.

Rove

Yes, it did. I just found this whole idea that everything was anonymous and that thesis, antithesis, synthesis, and history was moving itself out in a certain predetermined way, according to these anonymous forces, and we had to pass through the dictatorship or the proletarian. I mean, I found this all just to be insane. I didn’t like [Georg Wilhelm Friedrich] Hegel or [Karl] Marx; they both seemed pretty off the wall.

Riley

What about your affinity or lack of affinity for major Republican figures as you’re coming through? Were there people, particularly at the Presidential level, that you were finding an affinity for?

Rove

I was at an impressionable age. I remember [Dwight] Eisenhower because I was living in Colorado and this is where he recuperated from his heart attacks, but mostly I knew that he was the President. I remember [Richard] Nixon. My first political experience was riding my bicycle with a Nixon bumper sticker on my basket that I somehow scored, and getting beaten up in return.

I really liked Barry Goldwater and I can remember crying when he lost. I used to have a bottle of AuH2O. Do you remember that he had the little cans of gold water?

Riley

Yes.

Rove

I carried it around for years in my personal possessions. It got lost, along with other childhood items like my stamp collection and so forth. I thought Goldwater was the western ideal.

Riley

OK.

Rove

I remember going to all of the political headquarters in 1968, because Utah was one of the last states to have its delegate selection in what was a close race. It’s June of 1968 and there’s a close state convention. Literally, [Ronald] Reagan flies into Salt Lake to attend the Utah convention and takes it by storm. It was one of the last primary battleground states and it was also—It’s hard to think about this, but Utah was a battleground on the Presidential level. The Democrat and Republican Parties in the state had been pretty well evenly matched for the better part of a century, in part because the Mormons divided their congregations on a certain Sunday in the 1880s. People on one side of the aisle were Republicans and people on the other side of the aisle were Democrats. They’d been governed by a theocratic party of Mormons and they decided they weren’t going to get admitted to the union unless they split themselves up into Republicans and Democrats, and they did.

I think it was Tom Korologos who used to say—or maybe it’s somebody else—the problem with his family was that they were on the same side of the congregation as the town drunk that day. But Utah was a battleground state. Hubert Humphrey comes to Utah in 1968. That’s where he makes his break with Lyndon Johnson, in a speech in Salt Lake in the final weeks of the ’68 convention.

Riley

You mentioned running into George Wallace at that time.

Rove

Yes. I had a high-school teacher who really was very influential in my life, and he took us to see George Wallace, Richard Nixon, and Hubert Humphrey, all three of them. Hubert Humphrey was a forlorn figure, Nixon was a mechanical figure, but Wallace was downright scary. I didn’t put it in the book, but I went out, in response to that, and paid something like three dollars to join the Utah Chapter of the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]. It was really scary. I’d never seen racial anger like that.

Perry

Help us to see how your mind was developing at that time about the impact that a politician has on a roomful of people. You describe so vividly in your book that experience with George Wallace, but you also said Ronald Reagan had everybody on their feet and cheering too.

Rove

Right.

Perry

Obviously, not with racial demagoguery. What were you seeing about personalities and charisma in political figures?

Rove

I don’t know if I learned much at the time. Looking back, I was really—I would go to these headquarters of these Republican candidates and collect all the material. I’d get all the material and just devour it. I can remember that “Rocky” [Nelson Rockefeller] had the best graphics. He really had the best, most attractive, cool materials.

Perry

What were they?

Rove

They were done by Madison Avenue guys.

Perry

Mad Men.

Rove

Exactly. Remember, when he runs for reelection as Governor in 1966 he has talking fish in his TV ads, talking about cleaning up the Hudson River. And so you’re 15 years old and here’s this guy running these really cool ads.

Perry

And that’s where you get your idea for the dancing elephants?

Rove

No, no, I got that from my father. My father was a fan of German Expressionists, which are these very dour and very dark—during the Weimar period in the aftermath of World War I, but they’re around before World War I. The dancing elephants came from a sketchbook of a German Expressionist, who clearly was mad. And he had these sketchbooks filled with animals, most of them obscene. My father had not shown me the obscene ones, but he’d shown me some of this guy’s work. Then I came across, when I was on the College Republican National Committee—I remember the name of it—Dover Publications had all this stuff that had gotten into the public domain. They had a clipart book of this guy’s stuff. We found the dancing elephants there and turned it into the poster.

Perry

But you said, for that time, it in effect went viral, that you were into multiple, multiple printings.

Rove

Oh, yes, multiple. In fact, people say, “I still have my framed dancing elephant poster.” I was in Sacramento about six weeks ago and a guy said, “I was active in College Republicans when you were, and I have my dancing elephant poster.” If only our overlords at the Republican National Committee knew where we’d gotten it, we would have been in real trouble. I don’t think Bob Dole would have been happy. Bob Dole not happy.

Riley

Was Reagan somebody that was very much on your radar then?

Rove

Well, he was on my radar, but not as much. Nixon was a bigger figure because he won. I was 9 when he lost the first time, and 17 when he won, so he was a bigger figure than Reagan was. In fact, when I met Reagan for the first time, in 1976, I remember thinking how very old he was, and this caused me to make a classic misjudgment.

When the senior [George H. W.] Bush got ready to run for President, I remember that Mr. [James] Baker and 41 and I were talking about Reagan, and all of us were agreeing that he was way too old to become President, and that he was just ancient. I met him walking down a hallway in a hotel in Richmond. He was going to speak to the Republican Party of Virginia’s big fund-raising dinner, and Dot [Dorothy] Meldrum, who was sort of an old Republican battle-ax, about five feet four—you know, take a foam fire hose and wash her down for about an hour and she weighed a hundred pounds. She was a big Reagan person, as was Dick Obenshain, and I can remember walking with them and Reagan down this hallway, and he seemed ancient and old, and then he walked into the room and turned it on and he was charismatic and personable and really powerful. You could just see the magnetism when he wanted to turn it on, but walking down the hallway, he must have just been tired because he struck me as very old.

As I write in there [his book], I remember going to the Utah state convention in June 1968. In fact, I went to the airport and he flew in on a prop plane, one of those old United Airlines, two-propeller planes.

Milkis

Two-propeller plane, yes. They still fly into Charlottesville.

Rove

Admit it, you don’t want anything bigger coming into Charlottesville. You’re part of that “don’t extend the runway” crowd.

Milkis

Touché.

Rove

There are already too many of those outlanders coming in. But I remember going to the airport and it was a mob scene. It was really something.

Riley

You touch on Watergate here and a sense of betrayal. Did it cause you to recalibrate in any way your own political thinking or philosophy, other than just a sense of betrayal by this one individual?

Milkis

And you were at the RNC [Republican National Committee] when that was going on too.

Rove

Yes. I can’t remember whether I put it in the book or not, but I’ve actually come across the tracks of Donald Segretti. I don’t know if I put that in there.

Perry

You didn’t mention Donald Segretti.

Rove

As executive director of the College Republicans, I reported to RNC cochairman Anne Armstrong, who eventually becomes like a second mother to me. She and Tobin [Armstrong] became my second parents. I gave the eulogy at her funeral. In early 1972 I got a phone call from a young kid named Bill Henderson, who was at Johns Hopkins University, and he was the campus chairman there. He’s now a lawyer in Houston. He was a Texan, but he was going to Johns Hopkins, and he called me and said, “I’ve received a weird phone call from a guy claiming to be”—such-and-such a name—“and he wants us to infiltrate the [Edmund] Muskie campaign,” I think it was. My reaction is, This is a Democrat dirty trick, and so I went up and told Chairman Armstrong, and she said, “Well, call him back and tell him to play along, and I’ll alert the Committee to Re-elect the President.” She called Jeb Magruder, who was over there at the committee. He was later indicted and found guilty of stuff, but he became an Episcopal priest, one of the key players of Watergate. He was her contact at the CREEP [Committee to Re-elect the President] headquarters. They talked and she called me back and said, “Yes, follow through. String him along and we’ll see what happens.”

Well, the guy didn’t call back. But another CR [College Republicans], the Wisconsin CR chairman at UWM [University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee], Tim Gratz, got a similar phone call, the same MO [modus operandi], and the same reaction, which I thought was interesting. I talked to Anne and she talked to Magruder again. Gratz told the fellow who had contacted him he’d meet, and set up a meeting for his parents’ house, and CREEP sent out a sort of dumpy private investigator with a camera and recording equipment to capture it. It turned out to be—Tony Ulasewicz, who is a minor figure in Watergate, and they set up the elaborate trap at Tim Gratz’s parents’ house, and the guy never shows up. Later, it comes out that this is Donald Segretti, and that he had been warned by people inside CREEP that he’d been found out in Baltimore and then he’d been found out in Wisconsin.

Riley

Exactly. So, in the aftermath of Watergate, is there a political figure in a party that you’re looking to? You’ve already said that you thought Reagan was too old.

Rove

George H. W. Bush.

Riley

George H. W. Bush.

Rove

Yes. He gets made RNC chairman in 1973. I’m executive director of the College Republicans until February. I leave the building as he is being ensconced on the fourth floor. Then I’m elected college chairman in July and confirmed in the position in August. I meet him in August of ’73, and by October I’m working for him. So, during this really terrible year of ’73 to ’74, as the walls are tumbling down and the roof is falling in on the GOP [“Grand Old Party”/Republican Party] and flames are singeing every Republican—

Milkis

Metaphorically speaking, just for the record.

Rove

—I’m his Special Assistant.

Riley

Right.

Milkis

You got moved out of the basement, right?

Rove

I got moved out of the basement. I got moved up to the fourth floor, but I was not at the top of the pecking order, clearly, within that office. I was the lowest—I was underneath the receptionist and the driver, Don Rhodes. Part of the year I spent trying to rally support for Nixon, in particular southern states with moderate-to-conservative Democrats who were on the House Judiciary Committee. This was about the most appalling work a human being could have, because every time you think you’ve got some—I had to deal with a rabbi from Providence, Rhode Island, Baruch Korff, who was the big Nixon defender. I’m just all of 22 years old that year, and I’m clearly in over my head, doing things no human being should have to do. But that’s when the association with Bush began.

Riley

Right.

Milkis

And that’s where you met George W. Bush.

Rove

Yes, George W.

Milkis

Bringing him the car keys, right?

Rove

Yes, handing him the car keys. He has no recollection of me giving him the car keys.

Milkis

But you’re sure it happened.

Rove

But he has a very clear memory of the car. In fact, I have never really confronted him about it, but my sense is, from talking to his father and talking to his mother, that this is the famous weekend where he and his father almost go at it.

Riley

Oh, yes?

Milkis

Oh, really?

Rove

Yes, I think this may be it.

Riley

He’s probably set off by the car to begin with.

Rove

And if so, he was justified. The ugliest damn thing you’ve ever seen.

Milkis

I found your description of your first encounter with George W. Bush like on a movie set. He comes in; he’s wearing his flight jacket, and is charismatic.

Rove

Yes, and I’m the nerd.

Milkis

And you’re the nerd. Did you have any inclination at that point, or is this just such a short encounter that you didn’t know what to think? It’s just his son? You had no sense.

Rove

No sense.

Milkis

But you did pick up that you felt he was very charismatic.

Perry

And charming.

Rove

And charming, very charming.

Perry

In what way?

Rove

Look, I knew who I was. I was a complete nerd, and here’s this guy and he’s friendly. You could just tell that he had a lot of charm, and he had a lot of magnetism. It’s funny, when I’m around him now, he’s unchanged in that regard. You see him meet somebody for the first time, anybody. He runs into some server in the back of some hotel, walking down the hallway, and there’s an authenticity and a warmth there that’s revealing.

Perry

And you described his dad as being that way, so that when you would travel with him, you would see him talking to staff people and wait people.

Rove

It was a really important lesson. I’ve learned so much through my associations with them, a lot about things, but the most important things tend to be things about character. His dad taught me that they believe every person is worthy of respect. I don’t know whether it’s their faith or his formidable mother—41’s formidable mother and then 43’s [George W. Bush] formidable mother. I don’t know where it all comes from, but they’re absolutely right, and it’s a nice thing to live your life by. I also learned that people really appreciate acts of courtesy, and 41 is among the most courteous people in the world. He’s a really decent human being, a remarkably decent human being, and his son is the same way.

Riley

Do you share the conventional interpretation about 41 being sent to China?

Rove

The conventional being—?

Riley

Being that somebody was trying to get him out of town so that he wouldn’t be a plausible candidate.

Rove

Maybe, but I think, frankly, the selection of Rockefeller as Vice President had closed that off for him. I think the China thing was maybe a secondary thing, but I think also that Ford authentically liked him and trusted him. [Henry] Kissinger knew how problematic this relationship could be if it was mishandled, and they thought Bush had the temperament to do it, which he did. There was such overwhelming support on the national committee. The Nebraska national committeeman, Dick Herman, was the guy who was quarterbacking it, but the support within the party and within the Congress was overwhelming. And the selection of Rockefeller, by whatever machinations brought that about, signaled that it was unlikely that he, Ford, would ever consider Bush as his running mate. Back then, time horizons were very small. Bush wasn’t thinking ’80; he was thinking ’76.

Riley

Right.

Rove

So no.

Perry

Did you see Bush 41 as Presidential timber when you first met him?

Rove

I’m not, at that point, qualified to judge Presidential timber.

Perry

Not as a consultant, but as a person who’s just utterly fascinated with politics and Presidents.

Rove

No. Even then, I’m not qualified. At that point, I’m 22, and I’m sitting there saying, Geez, I’m honored to be in the same room with the guy. No, I’m not. But by the time ’77 rolls around, something happens. My experience as college chairman, and then going to Virginia, gave me a confidence that I hadn’t had before. So when he said in 1977, “Come to work for me. I’m thinking about running for President. I want you to run my political action committee,” I’m not overwhelmed. It’s sort of like hey, that would be really cool to do, I’m all for you. So something happens, just the natural transition from being a punk to a near punk.

Milkis

One of the things I’ve always found really interesting about you, Karl, is unlike a lot of people—conservatives or liberals—who had their critical socialization in the ’60s, you really seemed to love political parties. I think that comes out in your discussion of Watergate, that one of the things that really aggravated you was the way CREEP set up a parallel organization to the Republican Party and sapped energy. Where did this love of political parties come from? Did it happen by accident? Was it partly from your reading about people like [William] McKinley?

Rove

I didn’t stumble across McKinley until I was 47.

Milkis

Oh, we’ll get to that later.

Rove

I don’t know. Parties struck me as sort of a team. I wasn’t a young athlete, but I understood being a member of a team, and it struck me that parties were about being teams. What particularly upset me about Nixon, in part, was that this was all about him, at the expense of others. By doing what he did, he hurt himself, but he also hurt the cause that he claimed to have devoted his life to, and put at risk the careers of people who had been loyal to him.

Part of it also may have been when I grew up. I grew up in the ’50s and ’60s, in small-town Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. Particularly Utah in the ’60s was like America 1952. But I don’t know, I just have always—I’ve been reading a lot about Thomas Collier Platt, who’s a party man.

Milkis

Oh, yes.

Rove

And can’t conceive of something happening without the concern for the party.

Milkis

Don’t mess with my ports.

Rove

Exactly.

Riley

All right, you guys don’t start talking shop.

Rove

We won’t go there.

Riley

Is it the case that you’re a Bush 41 Republican? Do you distinguish that from a Reagan Republican at this time, or is that a different kind of conservatism?

Rove

In 1977, ’78, ’79, ’80, it’s a more conventional Republican. Ironically enough, Bush is the more southern of the two, being from Texas, but he’s also the more northeastern of the two, so he’s more like an Eisenhower Republican than a Goldwater Republican. Reagan is more like a Goldwater Republican than he is an Eisenhower Republican.

Riley

Right.

Rove

But I’m not certain I’m all that aware of it at that point. My loyalty was personal, in the man and the character, and then pragmatic in the belief that Reagan was just too old to win it, which was a stupid idea.

Milkis

So it wasn’t that he was too conservative to win it, it was like most people thought, you thought, it was the age?

Rove

Right.

Riley

Are you becoming more familiar with the son during this interval?

Rove

Yes.

Riley

That’s a piece that doesn’t really appear to me. You say at one point, when you join up politically, later on, that it was a reverse of the norm. That normally people are political allies and then they become friends, but you were friends with this man.

Rove

Yes, right. Now ironically, though, I see him more often in the ’77, ’78 period than I’ve seen him in the ’73, ’74 period.

Riley

Right.

Rove

He’s out in Midland and I’m in Houston, but he’s running for Congress and he’s coming to Houston some. Then a guy named Harry Treleaven, who is an ad guy from the east who had done Bush’s ’70 Senate campaign and is close to him personally, is doing 43’s congressional campaign. So he’s coming in and out of Houston and we’re hearing about it then. But actually, we spent more time together in the post-’80 Presidential campaign.

Riley

Sure.

Rove

I see him more, and particularly in ’87, ’88 is where our friendship gels.

Riley

What about his candidacy? Is there anything you recall about his congressional candidacy?

Rove

Well, I became a minor issue in the campaign. Richard Viguerie, with whom I’ve had a long and contentious relationship, had bankrolled my opponent for college national chairman, Terry Dolan.

Milkis

Oh, that’s right.

Rove

Dolan later goes on to form the National Conservative Political Action Committee, which is a Viguerie client. Viguerie makes tons of money off of doing the direct mail for them. But Viguerie is handling the campaign of the mayor of Odessa, Jim Reese, who’s running against Bush in the primary, and so they attack him by saying that Bush is associated with this Rockefeller Republican, Karl Rove. Nobody knows me. I’m not known in West Texas. At this point I’m a 27-year-old punk, and nobody in West Texas knows who I am, which is convenient, so that Jim Reese can say that a Rockefeller Republican is running George Bush’s campaigns. In those days, those were the swear words in West Texas. Anyway, so I become a minor issue in the campaign.

Riley

But then you become more personally acquainted with him later. In what context?

Rove

His dad is getting ready to run for President and we start talking. Bush is a consummate collector of gossip. He collects lots of information, political gossip, and filters it through and organizes it.

Riley

The son or the father?

Rove

The son. The father too, but the son is more open about it. The father’s more restrained about it, but is just as interested in salacious gossip.

Milkis

Salacious gossip.

Rove

So we start talking as his father is thinking about running for President. He, 43, was trying to take the measure of Lee Atwater, since he’ll ultimately become Lee’s overseer.

Riley

Right.

Rove

But having known how close I was to Lee, 43 and I started talking, and then just kept checking in. I had a lot of contacts around the country from my college days, and then for my political consulting business, which was increasingly outside of Texas and around the country. So in ’87 and ’88, we’re talking a lot.

Riley

I’ve got to ask you about Lee Atwater. You talk a little bit about it here, but I’m sure you’ve got more stories in your arsenal. Tell us about him.

Rove

It’s interesting. I put the big one in there [the book], which was the famous trip.

Milkis

That’s the first I’ve learned of the famous trip.

Rove

It was a lot of fun, and if you think about all those people who we met along the way who have gone on to other things or with whom we’ve stayed in close contact—

Milkis

It was really remarkable, the College Republicans.

Rove

Yes, of my era. It’s really amazing how many people I run into today from that time.

Milkis

You made a lot of important contacts.

Rove

Oh, yes. Without it the arc of my life would have been something entirely different.

Riley

Tell us about Lee.

Rove

Well, he was a very complicated person. Politically, he’s probably the most natural pol I’ve ever met, one of the two best political strategists I’ve ever met. It was partly book-learned, but mostly it was just sort of gut instinct. He really had a handle on how people felt and how to figure out what they were thinking. He was also the consummate bullshit artist. I mean, here’s a guy who literally reinvented himself. He’s a nerd in high school, decides he wants to be popular and date cute girls, so he teaches himself how to play guitar and plays beach music, then falls in love with rhythm and blues. But literally, he sets out consciously to re-create himself.

When he was my executive director, he was a great face man, he was a great front man, but one of his great talents was that he knew he was not up to detail and organization and activity, so he made certain he had a really able secretary who was. He spent all of his time chatting people up and talking on the phone and going to the right sort of intern gatherings in Washington, especially those of Senator [Strom] Thurmond. He had really funny habits. When he was nervous, he would tap his foot. So when he’d sit down, you could just tell he had something to say, and he’d say [impersonates Atwater], “Senator Thurmond has offered me the intern directorship in his office, and as you know, there are a lot of mighty fine-looking girls who come up from South Carolina for that program, and I’d like to take that job and ease my way back into South Carolina politics.”

This is about six months after he came to work for me, but I appreciated his candor. I’ve never had the idea that—I mean, change is inevitable and you want change, particularly when you’re young like that, and you want to grab it when you’ve got a shot. So we settled on a replacement, a kid from Kentucky named Kelly Sinclair. When Kelly came to work, I remember that we spent the morning talking about things in the office, how they operated, and Lee said, “Kelly and I ought to have lunch together, boss. You just let us talk.” So they went to lunch, and Lee left the lunch to go to Senator Thurmond’s office, unbeknownst to us, and never came back again. That was Lee, and you had to take Lee on that basis. He had made a determination that Kelly was up to the job and he didn’t need to spend two weeks more there, and he was off to his new job.

We remained friends. In fact, he was in Austin just before he had the seizure at the Phil Gramm fund-raiser in Washington. He’d find every excuse in the world to come to Austin as RNC chairman, though there was no Republican Party there to speak of. He would come there because there was a classic R&B [rhythm and blues] club, Antone’s, that would let him play.

Riley

Oh, yes?

Rove

Yes. This was apparently a good stop on the old R&B trail because they’d have all these old southern R&B artists come through. And he’d show up and jam with B. B. King or whoever.

Milkis

You’re kidding?

Rove

Antone’s Nightclub. [Clifford] Antone went to jail eventually for cocaine trafficking, but in his heyday this was Lee’s favorite excuse to come to Austin, to go to Antone’s and jam.

Riley

Did he have any blind spots politically?

Rove

His prime years were the years where his skills were best deployed because he was an intuitive politician. I’m not certain how he would have adjusted to the world of Twitter and microtargeting and cable TV. He was a guy who was—His insights into the 1988 Presidential race, that the Willie Horton thing bespoke a deeper philosophical weakness in [Michael] Dukakis that could be exploited, was a masterstroke. The famous story—and I’ve never figured out whether it’s true or not—was that he discovered the power of this while he was out at Luray Caverns one weekend the summer of ’88, talking to bikers out for a weekend ride, and having his own personal focus group.

Milkis

Guys on Harleys, a Harley focus group.

Rove

The Harley focus group. But Lee was a really intuitive political figure. He and Bob Teeter, a superb pollster and strategist, both had the same strength, which was they could read data really well. But both—especially Lee—had an intuitive sense of what worked and didn’t work, what was important and what was not important, and when it was that you needed to deploy it. If Bush had deployed, you know, letting murderers out of jail on weekend passes in July or June, it might not have worked as well as it did in September and October. And between Lee’s seizing the issue and Roger Ailes wisely saying, OK, we’re going to use this, but we’re going to shoot it so it’s a blue-gray color so nobody can figure out what race those silhouettes are.

Milkis

Silhouettes. I was just trying to come with the word.

Rove

It was shot using a revolving gate at Utah State Prison, at Logan, Utah.

Milkis

That came out after the other group, the outside group.

Rove

I think Larry McCarthy did that ad, which was not really widely seen. It was like an $8,000 buy, whereas the official campaign commercial was—

Milkis

Although it was projected quite widely.

Riley

Is it your judgment that if Lee had lived, that he would have made a difference in anything?

Rove

Yes. I think if Lee had lived, 41 would have been reelected and 43’s rise would have been impossible.

Milkis

Because of his political feel?

Rove

Lee’s political feel would have caused him to say, in ’91, you’ve got to be careful about this, and he would have. Even if Bush 41 had said I’m going forward with this, he would have found a way to better handle the campaign than it ultimately was handled. Talk about a dysfunctional campaign. In preparing for 2004, I went back and talked to [Michael] Deaver and Baker and everybody else who played a significant role in the reelect campaign, and the ’91, ’92 Bush effort is too late, too disorganized, no clarity of structure, no clarity of message, and a candidate who allowed himself to come across as distant and disinterested. The campaign ill-served the man.

Milkis

Did he also help Bush through certain policy battles? He got sick before the tax thing was resolved, right?

Rove

Right.

Milkis

So had he been there, do you think they would better—or was that just a no-win situation?

Rove

I think it was going to be what it was going to be. The question was, would they have handled the aftermath of it better, and could Lee have soothed some feelings about it? [Newt] Gingrich would have been Gingrich, but could they have done something to handle it? It’s never been clear to me how much policy role Lee had or wanted. I happened to be in Washington seeing 43 just weeks after the ’88 election, and it was the day that they were going to announce Lee as the Republican national chairman, which he had wanted forever. From the days that he was the CRNC [College Republican national chairman], he wanted to be national chairman. It had been leaked to the Boston Herald, and it was pretty clear that Lee had leaked it, and 43 said, basically, play along, because we got word that Atwater needed to come and see him. And Atwater came in and you could just tell, I mean the foot was going like this, and it he was just like, “Now, W., I know they’re probably going to say it over there, but I didn’t leak it, I didn’t leak it.” And of course he had. Bush sort of jerked him around a little bit and then said, “Don’t worry. Dad says OK; I’ve already talked to him.” But Atwater is very nervous and agitated. He wanted to be RNC chair. He didn’t want to go to the White House.

Milkis

Why do you think?

Rove

I have no idea.

Riley

Did that experience have any effect later on, when you’re trying to make a decision about which way you’re going to go, when you go in? Or did you just always assume you were going in?

Rove

No, no. In fact, as I say in the book, I didn’t think I would go. When you’re involved in a Presidential campaign, particularly when you’re a frontrunner and particularly after the primaries, people can’t help but think about the White House experience.

Riley

Sure.

Rove

And I can remember being literally horrified when Andy Card told me that the first meeting he went to at the White House, he walked into the Roosevelt Room and the woman holding the clipboard with a seating chart said, “Are you a Baker person or a [Edwin] Meese person?” Because they were so furious at each other that they seated them on opposite sides of the table. Everybody I talked to who had worked—Anne Armstrong, Marty Anderson, I mean everybody who I talked to who worked in a White House, going back to Nixon/Ford, told me something similar. I don’t know if you ever ran across Charlie McWhorter.

Milkis

I’ve never met him, but I’ve read about him.

Rove

Charlie, who as a young man had been Nixon’s aide, his Vice Presidential aide when there was only one Vice Presidential aide, apparently, in the ’50s, told me, “If you ever get a chance to do it, take it. It will be the best job you’ll have and it will also be the worst. The backbiting, the egos, the backstabbing is really incredible, but take it, take it and endure it, because it will be the greatest experience of your life.” And so, I’m OK at campaigns, I’m really not good at internecine warfare, so I did not go into the Presidential campaign sculpting a future at the White House.

Riley

All right, I don’t want to get too far down. Actually, there are a couple of things. Let’s back up, and tell us a little bit more about your experience with W., and how that’s beginning to emerge as you’re getting ready for the campaign and through the course.

Perry

Just to back up from what Russell said, you used the term at one point, we kind of slipped over it, but you said, “our friendship began to gel.” What does that mean?

Rove

We’d talk in ’87, ’88, and he’d share confidences and I’d obviously share confidences. Then, in ’89 and ’90, he started thinking about whether or not he ought to run for Governor in the ’90 race. My advice was, you can have the nomination and it will be an open seat. It’s a Republican state and you’ll inherit half of your father’s friends and all of his enemies, and they will come after you to get him. So, even though it’s a Republican-leaning state and you could probably win, they will do everything they can to embarrass your father by coming after you. At the end of the day, I think those were his instincts too, and the fact that I was willing to—I think, and I can’t speak to it, but I think the fact that I was willing to say the hard truth that he was himself coming to the conclusion of, sort of solidified that I was going to be somebody who’d shoot straight with him, and not just about his father but about his own circumstances. Everybody else was like, “Run, run, run!” And it was not the right thing to do.

Ironically enough, his father’s defeat in ’92 made it possible for him to run and win the Governorship unencumbered. His father, by 1994, is a popular figure again in Texas. He left the White House relatively popular, but he becomes even more popular, and the dynamic is entirely different than it would have been in 1990. But 43 clearly has a future and we’re talking a lot of politics, and he’s calling for gossip. What’s going on in this race? What’s happening with Claytie? What’s happening with other rising stars? I don’t know if he’s ever going to run, but I’m saying So-and-So, and would you be willing to help Florence Shapiro, who’s running for the state senate in Collin County? I’m helping him, unconsciously, build up some credits with people that he gets to cash in, in ’93 and ’94, when he decides to run.

Riley

And Karl, during the course of 41’s Presidency, you’re talking with him also about what’s happening in Washington? Is he bouncing ideas off of you in frustration?

Rove

Yes, but not as much. He’s clearly frustrated with the quality of the 1992 campaign and unable to do much about it, unlike in ’87, ’88, when he and Laura [Bush] picked up and moved to Washington. Now he’s got his own business career. He’s in the oil business, he’s got investors he’s got to deliver for, and he’s trying to buy the [Texas] Rangers, which is an arduous task. Its owner, Eddie Chiles, is in declining health and surrounded by financial advisors who are all jockeying. Once 43 can get a deal done with Eddie, somebody will step in and redo the deal up so they can get another fee or add somebody onto the tab. So it turns into a very complicated thing to both buy the Rangers and then to get the approval of Major League Baseball to buy it, so Bush is not in a place where he can take an active role in his father’s reelection campaign.

Riley

Do you have any piece of that, talking with him about the Rangers business too?

Rove

No, I’m just aware of it. But no, I’m not—

Riley

You said you’re not a sports guy.

Rove

I’m not a sports guy, nor am I a finance guy. I can read a P&L [profit-and-loss statement], but I can’t talk Wall Street language.

Milkis

So you know that was the best job in the world, to own a baseball team.

Riley

I want to get back to this because one of the pieces of leftover business, when we were talking about the Rovian way, a lot of that is about data, about your engagement in technologies and so forth.

Rove: Right.

Riley

Tell us about that, because your direct-mail work is pretty cutting edge, isn’t it? There weren’t a lot of people doing direct mail at that time.

Rove

Well, there were a lot of people doing it, but they weren’t doing it with such an emphasis on technology. The only way I could compete with the big boys was to be about two steps beyond them from a technological perspective.

Milkis

By sophisticated modeling.

Rove

Yes, and it’s not very—The first model we do is 1986, Kit Bond’s Senate race. We do the first vaguely sophisticated microtargeting. We called every single voter in the state of Missouri who’s not a Republican or Democrat primary voter, and we even called Democratic primary voters in certain blue-collar areas in St. Louis and Kansas City: “What do you think the number one function of government is?” And we gave them six options: promoting a free enterprise system, regulating the economy so everyone has a fair shot, protecting personal liberties, helping the poor, providing for a strong national defense, and promoting traditional values. “What do you think the second function of the government is?” And we’d give them the same list, randomized.

So, if somebody says my number one function is strong traditional values and number two is a free enterprise system, then they are a social conservative. If it’s reversed, they’re an economic conservative. If they’re help the poor and protect personal liberties, then they were liberals. We could cherry-pick the blue-collar types, who were populist on economics but favored strong national defense or traditional and conservative values. After categorizing everybody in the state, we targeted them accordingly. Deploying technology like this was the only way I could compete.

Milkis

How did you come to that? Where did that come from, this interest in modeling and the social—?

Rove

Well, because I understood voters were different and the question in every campaign is, who can you get to vote for you, and particularly, who it is that you, if you don’t do something—Who’s available to you, but only if you make a special effort? You know, who’s persuadable? who’s up for grabs? A swing voter, a ticket splitter, we had lots of different labels we were applying back then. But I knew you couldn’t win by just turning out the base. I mean, we were the minority party. This is the ’70s and ’80s; we were lucky to be alive at the end of the ’70s.

Riley

And whose work were you building on? You said there were big boys out there.

Rove

I had competitors here in Washington, most of whom were like Richard Viguerie and some various sundry firms. Viguerie was not real competition, though, because he had largely gotten out of the campaign business and into the lucrative business of creating organizations like NCPAC [National Conservative Political Action Committee] and then using direct mail to fund-raise for it.

Riley

So, the direct-mail stuff that you were doing was more conventional for the time than the survey?

Rove

No, it was unconventional. We had better ability to do computer work that other firms were slow to adapt, and that allowed us to do segmentation, to target messages to specific target audiences. We also turned out a superior product, with attractive graphics and copy. We could compete on price and deliver a better product, and technology was the way to do better. For example, it was then standard to label your fund-raising response reply card. We had computer printers that allowed us to personalize letters and an accompanying reply form that had your name and address and your source code on there. It also had a key code, so rather than having to type in the name and the address into the database, all you had to do was access that code number. And it was personalized, so that if you’ve got a history of giving $500 gifts, we ask you for $1,000 or $500. If you gave a $100 gift, we ask you for $250 or $100. It was much better than a label with a whole bunch of preprinted gift options.

It generated a higher average contribution and costs were roughly the same, and yet clients got a lot more money for each dollar they spent. We did a lot of testing and were very data driven and we were able to make it transparent to our clients, and I didn’t understand until much later how important that was. We made it so clients would fill out a little sheet with the day’s tallies, and in return, we would send them a report every week, showing how every mailing and every list was doing.

Before fax machines really became widespread, we went out and bought Qwip machines from Exxon Office Systems. They had these old prefax fax machines, using 1920s technology. They had a stylus that burned in a special piece of chemically treated paper. You put the phone into an acoustical coupler to establish a connection. So we would send these units to our clients for the course of the campaign, and that way we could transmit them copy. We’d call them up and say plug the phone in, and we’d hit the button and it would spin the copy, so we didn’t have to send by FedEx or mail.

Also, it allowed us to send them the reports. By the ’90s very early on, we got it so they could log on to a site and enter their own daily tallies for fund-raising. That would immediately update the database and pop up their reports, so they could see how things were going every day. I think I bought Rove.com around 1989. I’ve had the same email address since the early nineties, since DARPA [Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency] was still running.

Riley

All right, Texas. We’ve got to get you into Texas. You’ve been consulting with George W. Bush about running and he decides to run.

Rove

Right.

Riley

What’s your role going to be in the campaign?

Rove

Well, mad scientist. I’m going to be the general consultant and handle the direct mail, so the first thing we do is piece together the organization, the staff, and so forth. We have a very ragged primary. We have a campaign manager who had done a marvelous job in his previous race, but was in the wrong role in the primary. He’s a fine man, but could not make a decision. Bush is used to aligning authority with responsibility, saying, “Here’s the goal. You figure out how to do it and move. Tell me how you’re doing it and that you’re meeting your marks, but go do it.” And this guy just could not go do it, but that didn’t matter. There was no serious opposition for the Republican primary, because Bush, by force of personality, convinced everyone to stay out and give him a clear shot to beat Ann Richards.

Milkis

She’s a pretty formidable incumbent.

Rove

Really formidable.

Milkis

Kind of a star.

Rove

Oh, yes, a rock star, and a very adept campaigner. Bush had the most important insight, which is, “We’ll never attack her.” He would say, “We can do better. I think our state has not addressed this problem. Texas needs to deal with this issue,” but his attitude was, we have a limited amount of time to build ourselves up and take advantage of every moment to do that rather than attacking her.

Riley

How do you explain that? Here’s a guy whose father has been very publicly, verbally abused by this woman. You would think he’d want to rip her limb from limb.

Milkis

You think this is a redemption candidate in some ways.

Riley

Yes, exactly.

Rove

Well, everybody wanted to make it that. Again, that goes back to, is the big idea that I want to redeem my family because she said ugly things about my dad? Or is it that our state faces big challenges, too many kids are not learning to read, we’re at the risk of losing a generation, we have too much dependency on government that’s sapping the soul and draining the spirit, and our small-business people are drowning under a sea of junk lawsuits? What’s a more compelling vision? Pay her back for having said my dad was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, which was a very funny line, frankly; stolen, but a very funny line. Or talk about important things people care about?

Milkis

Do you think she, like a lot of people, underestimated him?

Rove

Terribly underestimated him.

Milkis

You anticipated my question.

Rove

Yes, terribly underestimated him.

Milkis

A lot of people have underestimated George W. Bush.

Rove

But even more than that is that she terribly misread that state’s attitude. She went out to San Francisco to a trial lawyers convention and called him “that Bush boy.” That was like hey, everybody laughed at the comment at the Democratic National Convention, so if I belittle him, they’ll laugh along with me. The contrast was stark. He’s out there talking about things people care about and she’s out there throwing slurs. Then when she goes to East Texas in September and calls him a “jerk,” that’s a key moment, because his response was to say, “I haven’t been called that since the seventh grade, and insults like that aren’t going to solve the big issues facing our state, which are making certain that every child learns to read, saving a generation of young people from a life of crime, ending dependency on government, and stopping the junk lawsuits that are keeping us from creating jobs.” It was like bam!

Then also, the famous killdeer incident had a big impact, because it showed—Her attitude toward good old boys was condescending. She felt she needed to placate “Bubba” by every September first going dove hunting in East Texas, outside of Dallas. Of course, she was not a hunter, she could care less, but it was a nice show and she’d get a nice picture for the newspapers. Bush went dove hunting and shot a protected bird, a killdeer, and when he discovered that he had done so, after a sharp-eyed television sports reporter noticed that the white markings on the bird meant that it was a killdeer, Bush’s response was not to deny it, but to dispatch a young aide to the game warden’s office to pay the fine immediately.

Milkis

That’s a great story, yes.

Rove

It was a classic moment because everybody—and I have to admit, I’m one of them who felt sick to my stomach when I heard.

Milkis

He wasn’t a hunter either, right?

Rove

He’s a hunter, but it’s not at the top of his interests.

Riley

Where did you learn to hunt, out west?

Rove

No, South Texas, Tobin and Anne [Armstrong].

Riley

When you went down there?

Rove

Yes. The first time was 1979, when Tobin and Anne invited me to go hunting. I’d hunted a little bit, rabbits and stuff, but not birds. When Tobin was dying, he called my best friend, Pat [Charles Patrick] Oles, who’s like a son to him, and said, “I want you and Karl to put together a group of guys and I’ll give you the first lease on the Armstrong Ranch.” And we still have it, 11,000 acres. It’s really a lot of fun.

Riley

Is that where [Richard B.] Cheney had his incident?

Rove

On my lease, and that was my lawyer. I was shocked that fact never came out. If you go back to incorporation papers of Rove and Company in 1981, my lawyer, the secretary/treasurer of my corporation, and my landlord is Harry M. Whittington Jr., and that’s the guy Cheney shot. The press corps never figured it out, but could you imagine the headline in the Washington Post? “Cheney Shoots Rove’s Lawyer in Sign of West Wing Tension.”

Riley

Did you get a funny feeling in your stomach when you got that news?

Rove

We could not get Cheney to make it public, and we needed to. It took until the next morning, before Cheney allowed Katharine Armstrong to feed the news to a reporter at the Corpus Christi Caller-Times. The White House press corps was furious with us for having hid this fact from the afternoon and to the next morning.

Riley

We’ve got a long way to get there. Texas.

Milkis

Let’s get back to the campaign.

Riley

The campaign. Is there anything else that we need to cover there?

Milkis

Let me just ask a really general question. I think it’s really interesting to look at Governors’ campaigns, and then the individual becomes President, like FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt].

Rove

Right.

Milkis

And that seemed to be a really signature Bush campaign. So what lessons did you draw from that campaign that served you well later on, serving President Bush?

Rove

We really needed to focus on why it was he would run for President. We needed to do a much better job of organizing it from the get-go so it would achieve the goals necessary. It also bespoke of an enormous ability to raise funds. We weren’t thinking about running for President in ’94.

Milkis

Of course not.

Rove

But we started to think that way after the ’96 election. One of the things that was clear was that he had the ability to draw lots of money from a wide range of fund-raisers and sources, like his father did. When his father ran for President, he had the Yale network, he had the eastern network, he had the Texas network, and then he had his congressional contacts. Similarly, 43 had his Yale connections, his baseball work, the oil patch, Texas, and then his father’s friends. So all of that really did point out that in a difficult race like this, you had to have a compelling vision that allowed you to make inroads in places where Republicans normally didn’t get the vote, and you needed to have a united party, which we were lucky to have in ’94 and hoped to have in ’98. Then we ran for President.

Milkis

Which issue do you think resonated most as the best in that 1998 reelection campaign?

Rove

Education, and that was both a temporary and a secular problem. If you look at the Republican vote in 1990, Ann Richards does better than a Democrat should in the Republican suburbs, and she’s getting not only women’s votes but men’s votes, because Claytie Williams was coming across as simply something that they couldn’t relate to. These were suburbanites, not West Texans. Education allowed 43 to bring those votes back, but it also allowed him to do well in Latino communities, where it was a huge issue. And the way that he talked about welfare and the way that he talked about juvenile justice, as well as education, allowed him to make inroads into poorer communities and to mitigate the animosity in the African American community.

Milkis

What percent of the Hispanic vote did he win in that election? I guess we could just look that up, but I’m just curious.

Rove

I want to say 35 or 40 percent in 1994.

Milkis

So it really anticipated how well he could do with the Hispanic vote, yes.

Rove

We won a majority of the Hispanic vote in the ’98 reelection.

Milkis

So in this race you really got to road test these ideas of compassionate conservatism that you had been developing. You beat a powerful incumbent with this.

Rove

There’s one other—I left his name out of this, but when I’m back—So I’m 20 and at the College Republicans, the American Enterprise Institute puts me on their mailing list and gives me all of their publications and says they will mail them to any chapter that we want. So I read Michael Novak’s essay on mediating structures, which just blew me away. Then, ironically enough, Michael and I become friends in 1989 and ’90, when I go on the board for International Broadcasting. And so I’m feeding Novak’s writings to 43, as well as Marvin O’Laskey’s work. That really becomes the heart of, as Bush coined the term “compassionate conservatism.”

Perry: What strengths and weaknesses are you seeing in Governor Bush now, in that first campaign? We’ve talked about the strengths of not going negative and having the big ideas and taking two or three issues. What other strengths? But also, are you seeing any weaknesses that you know you want to work on as time goes on?

Rove

He’s an unbelievable manager, which in politics means a strong leader. I’ve read Peter Drucker a lot, but I’d never seen it in action until I saw Bush. This idea of aligning authority and responsibility and holding people accountable for results, encouraging people, these come naturally to him. Maybe it’s ingrained in him. Maybe he picked it up at Harvard Business School. But he has this ability to lead and to lead an organization, to establish a tone, to set a goal, to keep the focus, to encourage people and to let them go execute. It was really amazing to see him, first as a candidate and then as Governor. In the campaign, not only the candidate but as the leader of the campaign, and then to see him as Governor. It was just mind-boggling.

He walked into office knowing he needed to have a good working relationship with Democrat Speaker Pete [James E.] Laney and with Democrat Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock, which could have easily gone wrong. I saw it go wrong with Bill Clements, who had a contentious relationship with Bullock. Laney was much more problematic for Bush in some ways; he was a really fine man, but the Republicans went from being a small minority to being a significant minority, and Laney had a very contentious relationship with him, and yet Bush managed to bond with Laney.

Bullock in particular, because Bullock is one of the most complicated people I’ve ever seen in politics. Early in 1985, Bullock is about this far away from concluding Bush is nothing but Ann Richards in pants, a lightweight who’s interested in the headlines. Bush makes a mistake of telling the press what the three men have decided in a private breakfast. Bullock is concerned Bush is a press hound and vows to take revenge on one of the new Governor’s key legislative initiatives. Bush beats Bullock easily. He instinctively [snaps fingers] understands how problematic this is and immediately goes to see Bullock and apologizes, saying “I heard you’re upset and you have every reason to be upset. I screwed up.” Bullock is completely blown away. Politicians don’t do that. Leaders do, but politicians don’t come in and say, “Hey, I screwed up. I got it.”

Of course Bush started his apology by kissing Bullock on the lips, because before you screw me you gotta kiss me. Pete Laney, to this day, if someone talks about it, he just starts laughing because it was so—Bullock apparently was completely discombobulated by it, because it was the kind of thing that he would have liked to have done but never found a moment to do it. I think Bush’s apology and the outrageous way he did it was the moment Bullock began to think, I can do business with him. It became a very close and important relationship.

Bullock scared people for two decades. I had a friend, Reggie Bashur, who has since passed, unfortunately. He had terrible brain cancer. He was a big lumbering guy, fearless. Bullock hired him. Reggie was a Republican, but Bullock hired him, and he lasted a week. He said, “I couldn’t take the pressure.” He said Bullock would summon people; people would get a page saying Bullock wants to see you, and they would jump up out of their chairs and run out of the room to see Bullock. And here’s Bush handling this contentious personality, and it just blew me away.

Now look, we all have weaknesses, and he didn’t have a lot, but it was clear that there was a difference once Karen Hughes came aboard. She was not there in the primary, but in the general election she came into the campaign. Bush had a tendency to say things that didn’t hit right. Once, he got into the habit of calling himself a capitalist, and Karen Hughes said, “Don’t you ever say that word again.” He sometimes had a great ear for feeling about these issues, but occasionally he could do better in finding the right word to say it. But he was really smart. He’s a quick learner and got into the pattern of thinking, What’s the best way to say that offhand thing?

Milkis

Talk a little bit about your relationship with Karen Hughes. It’s an interesting relationship; you’re both very different.

Rove

Yes, the High Prophet. Karen’s maiden name was Parfitt, so we all called her the High Prophet.

Milkis

She is tall.

Rove

She is tall, and she’s really smart and has a really good feel for how things are going to be perceived and played out. We’re friends, and there’s something about communicators. Communicators are thinking constantly about How do we position this? Particularly in the White House, I found myself on the opposite side of the communicators because I was more concerned about getting the policy right and they were focused on how do we get the policy explained right.

Milkis

Yes.

Rove

I have enormous respect for her, and Bush’s success would have been impossible without her. She really was particularly good at batting back the assaults from the Richards campaign in a way that helped Bush to rise above it. In the Presidential campaign, she would get stuck on a really good idea and made certain we all did too. After the New Hampshire election, we needed to give substance to the idea of Bush, and she was the one who picked up an old slogan that we had tossed around and made us all swallow it and eat it whole, “Reformer with Results.” It was corny and it was not durable, but it lasted for the better part of 19 days, and that’s all we needed.

Riley

I want to go back and ask one follow-up question about Bullock. Did his experience with Bullock in Texas in any way miscue him when he comes to Washington and is dealing with a different kind of government?

Rove

Yes, it does, in a way. It may be. It certainly put Bush in the mindset that he could develop relationships with congressional Democrats, but I think it’s an overstatement to say that he felt that everybody could be like Bullock. He was sophisticated enough to know that there would be different creatures in Washington, but on the other hand, it made him absolutely stubborn about the idea that he needed to try. This was a deliberate effort in the 2000 campaign, to say we were not Gingrich Republicans. This was not going to be [William J.] Clinton-Gingrich animosity, it was that we’re going to try to bring the country together.

In the White House the senior staff all get apportioned out to relationships with Members of the Congress, particularly Senators. There are not enough legislative affairs people, so they literally keep an informal list of who knows what Senator or major House player so they feel they can call you and be communicating with the President. I had to deal with Harry Reid because part of my childhood was in Nevada. Reid had come to feel that he could pick up the phone and say something to me and that it would be said to the President. So he’d call me and say, “I’ve just finished giving a speech and I didn’t read it in advance, and I called the President a liar and a loser. They didn’t tell me they were writing it and putting it in there. I didn’t mean to call him a loser; I meant to call him a liar. So, will you tell the President I’m sorry?” I’d be steamed about it and Bush would never be. It was like OK, I know they’ve got to do that.

I was there when his first instinct was he needed to reach out to Democrats. It was December 14, 2000, the day after he’d given the acceptance speech at the state capitol, after the Supreme Court decision, and the next morning he said, “I want to call Ted Kennedy.” And he talks to Kennedy before he talks to Trent Lott. We deliberately made George Miller, the ranking Democrat on Health, Education and Labor, the first House member that he met with. We found out Miller was flying from California back to Washington, and Bush said, “See if he’ll come and see me on his way back.” He came to Austin on the way to Washington. Bush said, “I saw what you said about education and an accountability system and I know you’ve had the courage to take on the unions on accountability. I want to be your partner in this effort, and I hope you’ll be mine.” While he didn’t have expectations, others of us did have expectations that the magic that he worked with Bullock could work in Washington, but it was a different kind of Democrat and a different situation.

Riley

Sure.

Rove

I think the one thing is, that did at least lift me, and I had the sense—I can’t speak for him, but I think it had the sense for him too. Bullock was strong, Laney was strong, and Reid was weak, and [Richard] Gephardt wasn’t willing to be strong. I think Bush regretted not having strong partners because—Look, Bullock and he didn’t agree on everything. Bullock did not agree at all when we had the votes to pass medical liability reform in the House, and enough votes that it could pass in the Senate. Bullock was not in favor of a cap on pain and suffering, but we ended up arriving at a deal with him. It was because he respected the will of the Senate, and was strong enough to say they’re entitled to their opinion and even stronger enough to say I’ve got a different opinion but I’m going to use my power to temper their opinion. And we didn’t have that, particularly in Reid, who was a completely undependable person.

Milkis

So he would have preferred strong party leaders, like a George Mitchell, or a Tip [Thomas P.] O’Neill would have been more suited to his—

Rove

Mitchell was not a guy that he trusted because of how he had screwed his father. Mitchell did not live up to the agreements that he made at Andrews Air Force Base. But an O’Neill, yes; someone who could give his word and stick by it.

Perry

Is that part of the relationship with Kennedy, then, that he feels that Ted Kennedy is that kind of person?

Rove

Kennedy can divorce the issues where he agrees with you from those where he disagrees with you, and Bush had read enough about Kennedy and knew enough about Kennedy’s views to know that he could be brought aboard on an accountability system as well. Kennedy had taken on the teachers’ union some and over an accountability system that measured progress; otherwise, you didn’t know whether or not the schools were achieving their goals. And a key phrase with both Miller and Kennedy was “disaggregation of the data.” Both of them had used that phrase. In the education reform movement this was low key, but a dead giveaway. If you said “disaggregation of data,” you knew the system was failing black kids, poor kids, Latino kids, rural kids, and hiding failure by aggregating all of the results. So when they said “disaggregation of data,” Bush knew they could be his allies.

Riley

Karl, I wonder if I could get you to comment a little bit more on the point that you just made about Kennedy, where you said he would agree with you in the area where he would agree with you without allowing it to affect—

Rove

Kennedy and Bush both had that ability.

Riley

Right. Is that a function of Kennedy’s temperament or is it a function of his unique electoral status as a Kennedy?

Rove