Transcript

Young

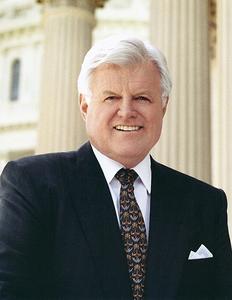

This is the May 31st interview on the Cape, the second in this visit with Senator Kennedy. Today we’re going to talk about school desegregation as a national issue and also as a particular issue in Boston during the [W. Arthur] Garrity period, when Judge Garrity was in control of the school system. So it’s all yours.

Kennedy

I think it’s important to put this in some perspective, understand where we were as a country, then also where we were in terms of the state and also in the city. The great failure of the founding fathers was to write slavery into the Constitution. We had a civil war that didn’t resolve these issues. Moving very rapidly into the late 1950s, we had bold political leadership from Dr. [Martin Luther] King and bold political leadership from the Fifth Circuit. Judge [John Minor] Wisdom, Judge [Elbert P.] Tuttle I guess, and many others made some very important decisions. After President [John F.] Kennedy was elected and after trying to deal with some of the foreign policy issues, in terms of the containment of communism, this generation of leadership looked around and said, “What do we really have to do here at home?” The most outstanding issue was the issue of discrimination and prejudice against blacks in this country—also against others, but obviously to focus on the issues of blacks and the remnants of slavery. They started to work on this issue, and all of that is for discussion at another time, what we were doing in the Congress during that period of time.

It was in the early ’60s when we had the Supreme Court decision on the issues of prayer in school. President Kennedy made one of his very important and famous speeches about supporting the Supreme Court and about prayer in our homes, in our churches, in our communities, that these were the locations for prayers, rather than it being prayer at school. The speech was controversial, but basically it was in support of the courts. The Fifth Circuit had made a number of decisions and judgments in terms of knocking down walls of discrimination, and it was the efforts at that time, with the real respect for the courts and the rule of law.

In today’s world it’s difficult to transport ourselves back and understand the significance and the importance of the role that institutions were playing at that time—institution of the government, institution of the courts, institution of the family. There’s been a rather dramatic shift and change about the family, enough said about the church, enough said about governmental institutions and whether they work and function and really represent, so that we’ve had such distrust about the central authority and also about the courts. All of them had a different role during this period of time, and there was high regard and respect for the courts.

So we had a number of issues on civil rights that were taking place in Washington all through the ’64 Act, public accommodations, the ’65 Act, eventually a ’68 Housing Act that did very little. But that was taking place there, and those stirrings obviously reflected themselves up into Boston, when leaders were seeing where we were going nationally about concerns about what was happening in the city of Boston. Boston was taking a look at itself and was finding nastiness about some of these issues, in the form of the parade, the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] parade in South Boston on St. Patrick’s Day, but it was in a very early period, in a very early stage.

As you come into Boston, we also recognized during this period of time that we had a lot of turmoil taking place. Watts had burned, we had the riots in Newark. During this period of time, there were inflamed passions about the war, inflamed passions in the ’64 Act. We had a long period of filibustering. We did eventually get that legislation through. We had the Kerner Commission a few years later that described what was happening in the country, that the country was increasingly divided between white and black, poor and wealthy, and nothing was really done. It was a report, and that was the end of it.

You’re talking about a city now, in Boston, that basically had a proud tradition in many respects in terms of its early history and about its role in the abolitionist movement and welcoming Frederick Douglas, and the development of the African-American museum up on Beacon Hill, which was a pathway for freed slaves. This element was part of its tradition, but it also was the melting pot of a lot of generations of immigrants with a lot of tensions and a lot of pressures, and the basic tensions were the kinds of issues that affect communities: issues on jobs, whether individuals and newer immigrants were getting jobs or weren’t they getting jobs. Issues on faith and church, which was central to so many of the lives of immigrants, communities, and neighborhoods. And also the sports teams. Bostonians were great sports fans. It was almost the only outlet outside the community. They didn’t have places to go, they didn’t have other kinds of distractions, so sports were a big element.

You had a great deal of anxiety even between the ethnic groups. I mean in 1958 President Kennedy had a slogan, “Make Your Vote Count,” meaning if you voted in ’58, even though he was running against a person who was not well known, people would not feel that their vote counted. So the slogan was “Make Your Vote Count” because it was suggesting that by voting in ’58, you were making a vote count for 1960, and that would bring more people out, it would increase his margin, and you know the political advantages of that. Well, there was a storm that broke out in the Italian community because they said “Make Your Vote Count” means your vote counts if it’s for Kennedy but it doesn’t count if it’s for Foster Furcolo, an Italian, and this was a slap at the Italians. This kind of sensitivity was extraordinary. That was typical of the kind of edge between Italians and Irish, different groups, let alone the tensions that were out there in terms of black and white.

So this is the climate and atmosphere you had. The city itself, up until very recently into the ’50s, was basically controlled by the Brahmins, one of the reasons my father moved out. Everything was controlled by Brahmins. The banks were controlled, the institutions were controlled, the financial opportunities were limited, as he saw it. That power elite used Boston, was very happy to use it and profit from it, but not really involved and interested in it. A very dramatic shift and change came subsequently, but that was really among the elites.

So you had a power group. The structure, in terms of the political structure, for running the City of Boston was called the vault, V-A-U-L-T. Just by its name, you can imagine who were the members of it. They made the judgment decision about who was going to be mayor. They made the judgment decision about who was getting money. They made the judgment decision where the leadership was going to go. They had influence in the city, but they weren’t engaged or involved in the city outside of the Boston Symphony, the Museum of Fine Arts, one or two other institutions, but not the life of the city or the people who were living in it. So in that atmosphere, in the post World War II period, you still had the boarding houses where single immigrants lived. Men lived in these boarding houses and worked, and it was a very different time in the postwar period. So you had these isolated groups that were living in that city, but they were isolated in terms of their community.

Suddenly, the awakening in this country about the importance of dealing with this issue of race started to stir this pot. These were communities that had resisted the post Second World War economic development, land development, urban renewal. The great developers of the time were called the Logues, [Edward J.] Logue from New Haven, another brother in Massachusetts, and they reshaped what was called the West End in Boston. As my grandfather—you go up there now, you’ll be lucky to find a few of the old churches that remain, but it’s completely different. It’s rows of high-rise apartments and these buildings destroyed completely the sense of community.

But the North End wouldn’t let them try and do it, they resisted. The South End resisted and South Boston resisted, and these communities came together at the time when what they perceived as outside forces were coming in saying they were going to give them a better opportunity, give them a better life, give them better housing and all the rest. They resisted, and they were successful. In other communities and other places, they were rolled over. The developers rolled over them and by and large, at this time in my life, it’s difficult to see how they were able to resist, knowing the power of developers. I’ve got friends obviously who are, but I will tell you, they have force and they have the ability to get their way, particularly in these urban areas.

So you have this atmosphere of isolation, of power, of the pride that exists in these communities that have been able to retain their own way, their own identities, against these outside forces, and increasing the security and awareness as generations were moving along. They weren’t making great progress, but enough, and they had fought very hard for the progress that had been made.

Now comes this whole instrument of change in the education issue and Brown v. Board of Education, the issues of desegregation and isolation, and how they were going to be dealt with in terms of trying to recognize that we were no longer going to be separate and equal. We were going to be one country with one history and one destiny, trying to move beyond the bounds of discrimination, and trying to knock down the walls of discrimination on race. Then of course in ’65 we began to knock down the walls of discrimination on immigration by eliminating the national origin quota system and the Asian Pacific Triangle, which were remnants of the yellow peril from the early 1900s. And we began to knock down discrimination on women’s rights and also on the disabled and the handicapped, or the children initially. Those forces were beginning to take place.

So the forces of change were coming, but the most obvious and dramatic was on the issues of schools and race. During that period of the ’60s, when I was involved as the United States Senator, at that time we met eleven and a half months of the year—there was no August recess. We got the Fourth of July, [Abraham] Lincoln’s week, and Thanksgiving weekend, and in several of those times, we were voting between Christmas and New Year’s, because we had civil rights and the war. We never got up here to Cape Cod until Friday night, until well after dinner. We were voting, busy all Friday afternoons, and we’d have to leave Sunday night because Monday morning is when everything started. It wasn’t this Tuesday through Thursday kind of routine we have now, in which the Senate has followed the House, with weeks off in between. We were completely involved and engaged in the life of what was happening in the nation’s capital.

The Boston School Committee was being challenged in courts from the early ’60s until the mid to late ’60s, about the school system. The school system basically had been established years before by the school committees. The schools in the black communities had grades from kindergarten to four and then they stopped. Then they had black schools that started from fifth grade to ninth grade, while the white schools went from kindergarten to the sixth grade and started at seventh grade. So for a black child to go to a white school, they would have to get out in the fourth grade, then go to a white school for two years, then get out of that and get on the white school track. It was framed in such a way that the grades—when children graduated and when the middle schools and the high schools started—were all completely out of sync. So it was virtually impossible for black children to go to a white school, and the other way around.

Young

The Boston School Committee, at this time, was responsible for this system.

Kennedy

The Boston School Committee was responsible for this, elected local officials.

Young

Who had the real power there.

Kennedy

The Committee had the real power, and they were basically following what had been established previously. What we were finding out, what we saw during that period of time, is the school teachers who went to the black schools were not nearly of the quality that were going to the white schools. The turnover of schoolteachers was much more dramatic than it was in the white schools. You had vast overcrowding of white schools and black schools, but you had schools that were in between, that were under capacity and yet there was no desire to move either the overcrowded whites into some of those schools or the blacks into any of these schools. They kept them either crowded or in these communities.

If there was any kind of anxiety in the white school system about the public schools, they had the option to go the parochial schools, which served as an outlet for them during this period of time, the ’60s, ’70s, earlier and certainly continued on. So the facts that were laid out in these legal arguments were just irrefutable in terms of how these schools had been set up and what the results were. It was clear or even clearer after Brown v. Board of Education that they were completely separate and unequal, and violating the Supreme Court. So the question was, how are you going to deal with these and how are you going to remedy this problem?

At this time, you had busing in Boston. You had a certain number, 18,000 or so out of 90,000. You had 18,000 children who were being bused through the Boston School System already and the issue and question that came on down is how are you going to deal with this situation? Arthur Garrity was appointed by the court to work out a system to do this. His proposal included increased busing. The total amount certainly wasn’t even—I mean, most estimates stated from 18,000 to 25,000, 28,000 maybe. It wasn’t this overall massive movement, but it was significant.

It operated in such a way that it moved children from these particular communities that I described earlier, into other communities, all of which were very isolated, individualistic, and had a separate life and culture and view and attitude, and it caused unshirted hell. The 1971 Supreme Court decision on the Swann case indicated that this was a legitimate issue, and during this period of time there were a lot of things going on. We’ll come back to those. If you look through the votes from 1970 through 1974, we had a whole series of actions on the floor of the Senate, where they constantly went after busing, enforced busing. We can come back to that.

I think the real issue for me was what was my role going to be in this period of time. We tried, through a variety of different undertakings, to play a positive and constructive role in this whole process, I think with probably marginal kinds of effect. But we were very much engaged in trying to find ways that we could be positive and constructive and non-inflammatory, and hands-on in the sense of being personally involved. We can talk about this in a few minutes, about personal appearances at rallies, where the anti-busers were, and efforts to meet with them, the prolonged meetings, a variety of different engagements with them as well as with the school committee and with other groups in the city: black representatives, members of the school committee, teachers, parents, members of the South Boston and Dorchester communities. We spent a good deal of time trying to find a constructive and positive role. We can get into that in more detail now if you want to.

Young

Yes, fine. This is very good. It sets the scene.

Kennedy

I think once Garrity got involved in this and once they started to draft the programs, we had the emergence of a number of local political leaders who were extremely demagogic in some instances. In some instances racist, not all of them, but in a number of them. Racism was a factor and a force with some, but not all. My own sense was I could have no influence on the racists but some influence on people who were concerned and bewildered and troubled and filled with anxiety and wondering what was happening to their children.

Young

Concerned about the safety of their children?

Kennedy

They were concerned about the safety of their children and they were concerned about the distance in case their children got ill or sick. People, I can understand, moved to different districts so they could be near schools that were good. People in that group didn’t have a lot of that kind of option and opportunity, but increasingly they understood what was happening. So there were a lot of very legitimate concerns. There were individuals like Louise Day Hicks, who was a very tough, shrewd, confrontational and bellicose figure, and Pixie [Elvira] Palladino, from East Boston, who followed me around and hassled me, who was small, short. I can see the pictures of these people in my mind just like you’re there, Jim, I can see them. You’re much better looking. This Pixie Palladino—short, pitch black hair and flaming eyes.

Young

Did she confront you?

Kennedy

She confronted, and always came out of nowhere. Louise Day Hicks, you could spot her a half a mile away, but Pixie Palladino, you walked into some hotel lobby and boom, she was there with all of her people and standing in front of you, not letting you move, wanting you to push her or do something.

Young

She was stalking you politically?

Kennedy

Yes, yes, any place, any public place. Any place it was announced that I was going. In any hotel, inside or outside. If she could get into the hotel, she got into the hotel. The lobby, top of her lungs.

Young

Make a scene.

Kennedy

Make a scene.

Young

There was a group that came down from Washington, the powder keg group, Alice McGoff.

Kennedy

Well, they probably came over. I saw these other groups. I knew they came down there, and they were mostly focused on Tip [Thomas P.] O’Neill at the time.

Young

Yes.

Kennedy

I mean they’d come by my office but never give—

Young

They had already given up on you.

Kennedy

They had given up. But in any event, we now have to look at where are the leaders in the community, where are the leaders on it? The most important leadership was the Catholic Church or Catholic communities. This was at a time when Cardinal [Richard] Cushing was in the last waning days of his life. He had been at full force during the ’60s but after the mid ’60s and into the ’70s, he became very frail. He was still the Cardinal, but increasingly inactive and separated from the figure he was, and this just arrived at full force on the scene. In very general terms, the church was missing in action. The local monsignors and the church groups all played the game with the local parish groups. You had some of the younger priests, but they were not effective, and the older ones played along. Some of them even went on the marches for the anti-busers.

So the moral issue of equity and fairness, and also the support for the courts and court decisions, the institutions, was completely lacking. We were basically an institutionless society. The business community was isolated. They did not become involved. They didn’t really become involved and engaged as you would for example, in our healthcare bill that was just passed, where you had the whole business community completely involved, and as they are today engaged and involved in the life of these communities.

Young

Why was that, do you think?

Kennedy

As I mentioned before, this was the beginning of the end for the old Brahmins. They weren’t getting their hands—they went to the Boston Symphony and the Museum of Fine Arts, but this wasn’t their business. They weren’t involved and engaged in the life of the community. They never were a part of this whole process, and they resented the people in this. So there was a complete separation. This is the cultural history.

Young

So they weren’t building a new kind of community like the business leaders in Atlanta were?

Kennedy

No, no, absolutely not.

Young

And they had stakes in this. OK.

Kennedy

No, no. They were completely isolated. None of them. We didn’t have people like— those listening to this audio won’t remember, but if they look through the life of Boston—a person like Lenny Zakim, who emerged in the ’80s as a person for reconciliation in different communities. He was a very important and significant force between the Jewish community and the black churches and the business community. He was an extraordinary figure and a force, and it was just the force of personalities.

We had people who came to us. There were some very important black leaders: the Snowdens, Otto and Muriel Snowden, and they were great supporters of my brothers and good supporters of mine, friends. Ruth Batson, who was very tough but reasonable, not unreasonable, and very highly regarded in the community. A woman named Ellen Jackson, who played a very constructive and positive role and endured enormous hostility and tremendous vituperation, just scalding, as she tried to help develop a program that would help solve these issues, by looking at whether communities and colleges would take some of the students. This was a good program and we might as well talk about it for a minute here. We’re getting away from the general into the more particular, and what they called the METCO [Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity] program.

Now you had places like Stonington College, an hour outside of Boston, eager to participate. It’s a Catholic school out there, eager to participate and working with other schools and colleges to bring some of the children out there and work out a program of education. We had a number of high schools, some of our first rate schools, in Newton and Brookline, that really reached out, I mean very courageously, in a very important way. They brought children in and we were able to—I was—to get funding for this program, eventually get funding for it. Eventually, President [Gerald] Ford and President [Ronald] Reagan killed it, but at this time we were able to get funding for it.

What was always lost in the Garrity proposal is that they developed these magnet schools, which were going to be schools with a great capacity for training in the sciences, in electronics, in other kinds of skills. The idea was to try and attract white and black children, and get the parents to understand that if their kids went to these schools, they would get advanced education. So all of that was out there, which was very constructive and very positive and very unique to Boston, but no one focused on it. All they focused on was the issue of busing. That’s all they focused on.

Young

Were the Snowdens and the others you mentioned, Ellen Jackson, were all of those also active, were they in the NAACP?

Kennedy

Yes. I mean, I’m not sure that they were members, but they ran—the Snowdens ran a community center in the black area that was very highly utilized. They were already involved in helping black children in education, I mean they were really very active. Ellen Jackson was not. She’d been actually a welfare mother and couldn’t get a job, but this hit. She had two or three children, and she just rose like a star in terms of leadership and eloquence and community involvement. There was a lot of anxiety in the black community, a lot of fear, physical fear. When the buses were going, I had one of my aides, Bob Bates, who was black, ride into South Boston, and they broke the windows.

Young

Have to get down on the floor.

Kennedy

Yes. I mean, there was real physical intimidation and real fear.

Young

And in the schools themselves.

Kennedy

In the schools.

Young

Didn’t they have to have police there?

Kennedy

Yes. Let me just stop.

Young

OK, it’s going.

Kennedy

You know, I can give you the account, the personal involvement we had in this, besides the series of meetings. You can make those part of the record, rather than my reading them through. I think the most dramatic, I expect, was the opening of the schools in 1974.

Young

Right. Before we get into that, could I go back to where we stopped. You were talking about where were the leaders, and the Catholic Church was missing in action, the business community was not involved. The activists?

Kennedy

Labor was not involved.

Young

Labor was not.

Kennedy

They had the difficulty of getting any blacks into the apprenticeship programs you know, for the skilled workers. Actually, I think [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan, under [Richard] Nixon, got the first ones moving in that area, but that was certainly true up our way as well. So they weren’t involved. They didn’t want any part of this. Those are the principal kinds of—I mean if you get the church, the business, the labor groups, and then you have the various organizations that represent different communities, they’re not really effective in this kind of a situation.

Young

So the Italian community wasn’t involved.

Kennedy

They weren’t, because they had their own—their children were going to be bused into Roxbury, that was their concern. It wasn’t that their schools—their children were going to have to go downtown. So they were very upset by all of that.

Young

And you referred to Stonington and the places that on their own—

Kennedy

This was the result of meetings of Ellen Jackson, and the organization called METCO, about involving other educational institutions. There were some people who were trying to do this and they established outreach programs with the colleges, and established some movement with some of the schools in the suburban areas.

Young

Judge Garrity’s orders required that the integration be accomplished within the city limits of Boston. During this controversy, there was a good deal of thinking, I guess Bob Coles and maybe a few others felt—and Kevin White put forth this position that the middle class in the suburbs had to be involved in this. Was that a real issue?

Kennedy

Well, I think there was a recognition that it wasn’t anything that you were going to be able to require. The question was whether you could—was there any opportunity that you could encourage them to get into this system? Coles was very eloquent about the disparities in communities and the root causes, but of course then, as he pointed out, part of those who had just moved into the suburbs were only a stone’s throw away from living in the other communities and didn’t have many advantages, and had as much or more resentment. That was certainly true about some of the communities, but it wasn’t true about all of them.

Young

And then what about the people in office—the Governor, the State Board of Education, the mayor? Were they exercising any leadership? When this situation really got hot, what were they doing?

Kennedy

I think Kevin White was trying to play a more positive and constructive role, but I have no clear recollection about it. I think Governor [Francis W.] Sargent was there, but the other—

Young

It’s just who was urging the people of Boston to cool it and to go along with this, and urging the whites to try to accept it? Was there any voice like that?

Kennedy

Well, there were probably some isolated—I was talking more about the generalizations about the larger community. I think there probably were people. Eventually we got some people from the Justice Department. Stan Pottinger came up. You have some individuals, and I’d have to go back and take a look at it. I was talking rather about the generalization, about the general climate and atmosphere about where this all—there was no one who stood out. Governor Sargent, at that time, I don’t remember him being very much involved. Ed Brooke was in the Senate, and I think he was trying to talk to leaders. I don’t take anything away from Ed, but I don’t think he had much of a role to play on it. Members of the Congress, I think Tip O’Neill was initially rather empathetic and sympathetic to the anti-busers, and then I think as he began to understand the magnitude of this issue, was willing to stand up and resist the onslaught of demagogues on this.

A number of things went on in ’67, when we have the—’66 is when the school committee is criticized for its program, which is just a continuation of the existing situation, which was going to be eventually struck down. So we had an election in ’67, Kevin White against Mrs. Hicks, and although I didn’t support Kevin White by name, we talked about the increasing hostility and what this meant for the future of the city of Boston, urged people to vote in terms of their broader interest of obeying the courts, and also about calm and progress. This was certainly interpreted as support for Kevin. Then, as I mentioned earlier, we had the Kerner Commission that talked about the broader issue of division, which was taking place across the country, that said the Congress and the country had to find ways of moving towards a greater reconciliation in terms of these divisions that had taken place. Then we had the Swann case, which was very important, that upheld busing. So we’re basically into continued deterioration.

Garrity has got the case, ’72. In ’73 we have a lot of debates on the floor of the Senate, saying no busing until all the appeals come in, a series of different—court stripping. We had President Nixon, in March, saying that he is strongly against busing. Then we had this conference, that I always remember very clearly, between the House and the Senate, as we were trying to get money to help on reconciliation. I think it was a community services program at that time, to help communities that were going through various court decisions. Congressman [John M.] Ashbrook from Ohio, telling me that we weren’t going to get a conference report if it had any money for reconciliation, that I didn’t understand. The Republicans, he said, the President, wanted to see Boston burn. They wanted to teach us a lesson. If that’s the only way they’re going to learn, it was going to burn, but it was going to be over his dead body that any money at all was going to go for reconciliation. I remember that being one of the cruelest and nastiest comments. He was an old, gray-haired Congressman who had been in there for a long time, and I was still reasonably green.

Young

Was “Boston” Ted Kennedy?

Kennedy

It was the Kennedys, yes. They saw the opening on this thing politically. I mean, it was very obvious at that time. Nixon understood it. As he was opposed to the busing, they were raising the oil import fee. I was always interested—I mean, we have an oil import fee that was put in by Lyndon Johnson in 1958, in order to get the civil rights bill, to get [Robert S.] Kerr of Oklahoma to support the civil rights bill. They put an oil import fee in. At that time it used to cost twenty cents to produce a barrel of oil, and they put a $50 oil import fee, and by this time it was $2.50 and still, it was fifteen cents to produce. The profits that they were making from South Boston were extraordinary, and yet they were all prepared to pay that and vote for Richard Nixon and the Republicans because they were against busing. They didn’t vote their economic interest, they voted their fears.

Now in the spring of ’72, we have [George] Wallace coming up across the country, winning these primaries—Michigan, Maryland. So this whole issue about what is happening in Boston is in flames across the country, and we had the HEW [Health, Education and Welfare] in 1973, cutting off all the federal funds to the Boston school systems because it was segregated. We had, as I mentioned before, the whole series of amendments on the floor, which we resisted, but all of which were carried, and one very close in the House of Representatives that was a constitutional amendment.

So in 1974 the tensions are extraordinarily high. We have the Garrity plan, which is the court-ordered busing. In the summer, just incredibly tense. There were incidents taking place all over the city of Boston.

Young

Just before the schools were going to open in September.

Kennedy

There were a series of public rallies, and the emergence of this group called ROAR [Restore Our Alienated Rights]. It was an appropriate name for them. In August, I did a television spot urging calm. I think others did similar kinds of television spots, urging calm, and talking about support for the courts, which we began the conversation about. At that time, there was enormous animosity in many parts of the country and I think probably even in Massachusetts. There was no respect for institutions and institutional leaders and for court judgments and court decisions, which is not where it’s at today, but it was at that time. They had a very difficult time.

Young

It was breaking down.

Kennedy

It was breaking down. Then I issued a statement and comment in September, just before school. On September 9th school was opening and there was a question in my mind about what’s the role for that particular day. There was a lot of focus, a lot of attention obviously, the whole city and the state and parts of the country were watching what was going to happen, and particularly in South Boston. I mentioned about how I had a staff member—Bob Bates, who is black—go down on the school buses and into South Boston, where they were having the children attend school for the first time. There were swarms of police down there and metal detectors, and a lot of people yelling insults at these kids, and I think they hit the buses that went on down to South Boston.

I went over to South Boston to see this, and it was just a nasty, nasty situation. It wasn’t going to do me any good to walk in and walk out of the school, but I just went over to observe it. Then we knew that there was this big rally at City Hall opening day of school. It was in my mind whether to go to that or not go to that. I mean, I was really unsure of what to do on that. I felt that I should go and that I had a responsibility to go, it was my city and this is the issue that we care about, and there are good people who are trying to find out what this whole struggle is about, and maybe they would be willing to listen, that this was the focal point of this whole city’s turmoil and that it was better to face this issue. I’d issued the statement, I’d done television, and done that aspect of it. I always felt that that was somewhat distant and it wasn’t engaging them. I met with leaders, but it was a small group of leaders. It seemed to me that when you met with leaders, you got the worst of it because they’d come on out and they’d all talk, and you’d come out and talk, and you weren’t able to—you just saw the ones whose minds were made up in any event, and you weren’t able to reach the others who might be willing to listen for a while.

Young

Over the summer you had been in a lot of meetings, according to [Boston office director] Mary Frackleton’s notes.

Kennedy

I met with the school committee, I met with teachers, I met with parents. I met with the black community, including Tom Atkins, who had been the attorney for the blacks, and the Snowdens and Ellen Jackson. We were in constant contact with all of that community, so we had a series of meetings. Eventually, I believe it was after this time, I’m pretty sure it was, I met with ROAR, and that’s another meeting that I’ll describe. In any event, we pulled up to City Hall and there was a crowd, several hundred, outside the JFK [John Fitzgerald Kennedy] Building, not far from in the middle of that red brick area between City Hall and the JFK Building. There were several hundred there, and they had bullhorns, and there were speakers going on. I don’t remember being necessarily invited to it. I don’t know whether they invited all of us to it. I kind of think they didn’t. I think they just were having this rally against it.

So I thought I ought to go over there, but I thought I ought to go by myself. I didn’t want it to look like I was coming over there with a group—that would be a different feel for it. So I just walked across the mall there, towards the crowd, and as I got closer I heard them say, “There he is, there he is, there he is.” Then they started yelling insults, and they had their own security. They kind of opened it up, a way for me to get on the podium. I think it was a fellow named [John] Kerrigan, who told me, “What do you want to do, speak? You’re not going to speak. You’ve taken away our rights, we’re going to take away your rights, how do you like that?” Then they sang God Bless America and all turned their backs to me. Then they turned around and they had some more insults.

Young

Was Louise Day Hicks on the podium?

Kennedy

I can’t remember.

Young

But Kerrigan was one of them.

Kennedy

Kerrigan and Pixie Palladino. It was mostly that group. I don’t remember clearly her being there, she may very well have been, but it was the principal leaders of the whole organization. So then after he spoke, another person got up and gave a fire and brimstone speech on this thing. After he spoke, I went over towards the mike, and they put their hands on the mike and wouldn’t let me talk. Then they all turned their backs and sang another song. So I had a feeling that this isn’t going to work, this thing isn’t going to work.

After that they were still yelling insults, and the people on the stand started yelling insults and being nasty and saying, “Why are you being nice to him?” “Well, we’re not going to let him talk. You shouldn’t.” It was an increasing rise of hostility, so I thought it was better just to—there was nothing more I could do confrontationally. I mean, there wasn’t any ability to confront them because they weren’t going to let me talk. So I started down. There was another stairs on the other side, and I started down. They opened it up a little bit but not too much. They opened it up and then they raged insults to me and my family and blacks and all kinds of things. “One-legged son, send him to Roxbury” and stuff like that. It was just a very nasty day. Then I can remember there were some things being thrown, and then there was some pushing and shoving.

I remember stopping on the way because I always intuitively know that crowds like these are cowards, basically they’re cowardly, and they don’t—if you’re facing them, they’re much more reluctant. If you wait around awhile, they’ll get emboldened, but they don’t. So I’d stop and they would stop. They’d yell but the stuff wouldn’t start. I stopped a couple of times and they sort of stopped and continued to yell. Others began to come on out at the top, but the front ones coming at me just stopped. They didn’t continue to come out.

Young

Were they coming at you?

Kennedy

Yes, following me. I mean coming around and going to the sides, but not in front of me. They didn’t get in front of me. I saw the doors of the JFK Building, and then I stopped a couple of times but each time I stopped, they kept getting closer and closer, and finally there was about 30 yards to go. That’s when I went towards the doors and they opened those doors and then boom, they threw rocks and everything, crashed through those windows. I went in and they didn’t get in the building.

Young

Did they try to get in?

Kennedy

They came up to the edge. They had police inside the building and they didn’t come in, they just yelled and broke the windows.

Young

But you didn’t have a police escort.

Kennedy

I didn’t. Not there, no. So I was headed back and I thought, Hell, I might as well go back to Washington. Then I got in the elevator and was going down to go back to Washington and then I thought, Well, they’ll say they ran me out of town. So I thought I’d better stay around for a while, so I rode upstairs. Bob Bates, as you know, was black and he was just on the outskirts. I picked him up and he was on the outskirts watching this thing from the side, and I wonder about his observations, what he saw.

Young

That must have shaken you terribly.

Kennedy

Well, that was a really nasty crowd.

Young

Was that the first time you had ever encountered that kind of nastiness?

Kennedy

Yes, I suppose. Yes, yes.

Young

And it just erupted. There wasn’t a cheerleader there.

Kennedy

No. It all fed on itself. Then I had a situation that I always thought was more dangerous, and that was when we were in Quincy at an event out there. It was something in the mid-morning. I can’t remember what the particular event was. There were several hundred people on something else, some domestic issue. At the end of it, we had heard that ROAR was out there demonstrating, and there were a few hundred of them outside. They were picketing. So I thought, Well, we still have to go outside. There was a fellow named Jack Crimmins, who used to drive for me during this time. We walked out and Jack usually stayed with the car, but he came into the back of the meeting hall and then we went back out.

They were yelling and had signs, and there were several hundred and I thought, Well, we’ll get in the car. We came over to the car and all the tires were flat, and they had put dog doo under all of the handles and on the windshield, so you couldn’t move the car. Now they are around, and there’s very little security around there. I don’t think we had any at this time and there were several hundred of them. So I start to walk, and I don’t know where the hell I’m walking. I have no idea where I’m walking. I’m talking to whoever was the aide at that time saying, “Do we have a friend around here, do they have a house? There must be somebody around here who’s got a house. I could just walk on in and stay in his house until we can get out of here.” They said, “Let’s see, which street are we on?” They didn’t know, so we walked and they all started walking behind. There was no one else in the streets, and they were taunting and yelling, and I didn’t have the slightest idea of where to go. I just knew we had to get moving. I didn’t know if I could see a house or didn’t know where the hell I was going to go.

Young

Was this a residential area?

Kennedy

A residential area. We walked and then the crowd was beginning to build and was getting nastier. Then, out of the corner of my eye I saw the subway station. I looked at Jimmy King, who was with me then, and I said, “Jimmy, we’ve got to get in there.” But of course I thought, My God, I’ll be in the subway and I’ll be waiting seven minutes for the subway to come. I knew if I walked and indicated it, they’d all go over and block it. So I had to walk in sort of a different direction but fairly close to it, and then they kept going and Jimmy King went on over to the door, and when I got about 50 yards I turned and they said, “He’s headed to the subway station!” So then I ran into the subway and they all ran after me. I got in the door and Jimmy King kept that door shut. They were all trying to come through the one door, the only door that they could get in. I get downstairs, and he held that door closed. The subway came and I got in it, and they’ve got rocks and everything, hitting the subway cars all the way back into Boston—

Young

So they had the rocks with them.

Kennedy

Yes, they had the rocks with them on that day. Those were the two times when I felt that there might be—I mean, I was thinking. I wasn’t as worried about security as I was thinking about how I was going to try and get out of this situation.

We had a third event in my office that wasn’t physically threatening, where this Pixie Palladino and this woman from South Boston, Rita Graul, I’ll never forget her name. I’ve tried in preparation for this to find out if she’s still alive. I mean, it isn't difficult to believe that she is still alive, because I’m still alive. If they could ever get her, she’d be—we ought to write down that name, because if she’s still around, from South Boston, she is something else. Rita Graul, and she was a member—she had three children in school, and two of them were going to be moved, bused. She did not say a word.

We went into this room in my Boston office, and there must have been 70 of them. Seventy of them came in to my office, so I was sitting in the seat and the whole room was just surrounded, and each of them spoke one at a time, for seven hours. Seven hours it went on, until I realized, I’m not leaving here until the last one leaves. The last person out of that room was Rita Graul, and she never even talked. I thought, If I was going to be against the German lines, I wanted Rita Graul to be in that foxhole with me; she’s the toughest cookie I’ve ever seen. “Oh golly,” she said, “now we’ll hear from Mary over here. Mary O’Sullivan. You know the Sullivans used to be a great source—” She introduced everybody, knew who they were, where they came from, where they came from in Ireland you know, just to rub everything in. “Why are you torturing her kids,” you know, “she’s got two nice children, Megan and Sean. Sean was on the baseball—he can’t play baseball any more, Senator. Do your kids play baseball?” Saying it in a quivering voice and talking, “Why are you doing this to us and why are you doing this to me?” Seven hours of it.

Young

So there was a story like that from everybody.

Kennedy

Everybody.

Young

Were there any men there?

Kennedy

Mostly women, very few men. The women, they knew how to—

Young

They were the real aggressors. Was that true in the crowd?

Kennedy

In the crowd too, some men, a lot of women. I think there were more women than men, but there was a fair number of men. That was just—I mean, that thing was so long, and the television was outside, waiting to have some kind of—they all left, they couldn’t believe it. They said, “When’s the Senator—?” I said, “I’m staying here until the end of it.” “When are we going to meet again?” they wanted to know. “When do you want to meet us? When are we going to meet again?” They just wanted to have meeting after meeting after meeting.

Young

And vent? Was it mainly venting?

Kennedy

To vent, venting.

Young

It wasn’t threatening?

Kennedy

No. That wasn’t physically threatening. I always thought I’d get some begrudging respect from the fact that I was meeting with them. Having gone through this process for a long time, I mean, this was more intense than others.

Young

You’re not hiding.

Kennedy

I’m not hiding. I’ve gone, up in Gloucester, when they were closing the fishing place, and gone up and walked in that hall of 500 fishermen, and they’re booing you, just booing you. And they get up and speak and you stay there two and a half hours. Remember that, Vicki? We went into this hall and they were just booing and hissing and why haven’t you done this and why don’t you do that. At the end you get a standing ovation. You can turn it around; well, he’s going to stand with us. He should have done it but he didn’t, but there’s a sort of begrudging—it was hard to feel that sense, which I’ve seen as a politician. Hard to get that sense with any of these groups. It was just too deep, too intense.

Although in other campaigns, I did house parties in these areas, Dorchester. I wish I had the list of the people who had me in, but they would bring people on in. I did it in other campaigns and people would come on in to that thing, and they ended up giving me some support. I lost a lot politically in those areas, but there were decent people in all of those communities. I went back in all of the communities to some extent after this subsided.

Young

Oh, you did?

Kennedy

Yes.

Young

You didn’t just stay away.

Kennedy

We went back into a number of homes in Dorchester, West Roxbury, and asked people to come on in. There were small meetings but word gets around that we were doing it. In Charlestown they were livid, and that was the home where my brother did so well. He got 95, 96% of the vote and all the rest, and they loved the Kennedys. They were so teed off at me. After the Charlestown parade, I went over—I’ve got this very good friend, Gerry Doherty, who was a representative in 1962, and was a supporter of mine in ’62 and helped organize local legislators for me. Gerry, everybody knew him. He was very courageous because he had a Kennedy bumper sticker on, and he wouldn’t take it off. He had a reception for all the people at the parade, the parade leaders.

Young

This was up on Bunker Hill.

Kennedy

Up on Bunker Hill. He invited me over, and I went over there and we had a great reception of people. They were looking out the window to make sure that their neighbors didn’t see them in there, but they still—they all invited me to come down to this—there’s a pub down there called Sullivan’s, and I was a member of the Knights of Columbus and I gave them my sword over there and I told them that they’ll probably put that sword in me if we go over there. I resisted that temptation. I mean, that would have been a drunken brawl down there. But there was some sense that people were going to try and find a way of coming back, reconciliation.

Young

Your brothers never had this kind of experience.

Kennedy

Not that I know of. I was down with my brother in West Virginia and we had people individually yell at us and things like that.

Young

Heckling and all that, but this is something very different.

Kennedy

This was very nasty, very nasty.

Young

Could we have a break for a moment?

Kennedy

Yes.

Young

This is a resumption of the interview in which I neglected to say at the beginning that Vicki Kennedy was attending the interview with us.

Kennedy

Playing the indispensable role of the electrician.

Young

Now serving the indispensable role of having mastered the equipment that totally confuses me, recording equipment.

Kennedy

I think one of the real dilemmas I felt during this whole period of time is on the one hand, the leadership that had been provided by my brothers in the whole area of civil rights, and the involvement of my brother Jack and obviously Bobby [Kennedy]. The principal reasons of his [Bobby’s] candidacy were the poverty issue and the war, there were always those two. So much of his life had been the deterioration of the quality of life in the inner cities, particularly among poor blacks and poor whites. People had commented during his candidacy that he’s the candidate who could bring poor whites and poor blacks together in a rather unique and special way, which I think was very true, and that had always been impressive.

My service had been on the focus of opportunity for people in the areas of education, health, jobs, housing. Those issues, and knocking down the walls of discrimination—I spent a lot of time on that issue in the Senate, and I think the overarching issue for our country and society is how we are going to deal with the forms of bigotry and discrimination. I think we were and are the revolutionary society. No country, no culture, no history has ever made the progress that we’ve made on race and religion, on ethnicity, on women, on disability, and also now I think in terms of gay rights. If you look at what’s happening in so many different parts of the world, it is so incremental in any of these areas, and we have made enormous progress. There’s still incredible problems to go, but we start off with that.

Still, there are no political forces that are alive in our country that want to go back, but I always call this the march of progress, which is this period of time in American history. There’s no politician saying let’s go back. They’ll come along the edges about courts and let’s have strict constructionists, and they will try and limit the possibilities of voting, and then they’ll play up emotions and tensions in terms of race. I mean, I see that even now as we’re dealing with the immigration bill, the idea that Jeff Sessions will offer an amendment saying we’re not going to permit the earned income tax credit for people that are undocumented, even if they are in good standing the rest of their lives, although we don’t do it to murderers and rapists and pornographers or child molesters or anything else. So you still have elements of that kind of attitude alive and well, and people willing to exploit it. But there is no political process to try and reverse these major elements of progress that we’ve made in our country and society. Enormously important, and President Kennedy and Robert Kennedy were very much involved. I certainly worked on them while I was in the Senate and here you have internally these two factors and forces that are in contrast here. As one who has tried, in the Senate, to find common ground in different areas, and I’ve had some ability to do so, you couldn’t find common ground on these.

Young

You couldn’t.

Kennedy

And that conflict was very real and very significant and very powerful, and was something that was obviously perplexing and distressing as life went on. Eventually this part of my career, I could still work on both of these areas, and we have strong support from both communities again. But for that time and for that period of time, when the country was in turmoil with the war, we had cities that were burning, and then both the tragedies, not only in my family, the loss of Dr. King, all of this turmoil and conflict were so close to the surface during this. It was a time of enormous convulsion just in terms of how I looked at the scene during that period and how we looked at the future.

Young

Were you discouraged?

Kennedy

Discouraged, yes. I mean I basically had felt that everything was going to get—a person is basically hopeful. I just saw things getting worse. There was a conflict of what I felt in terms of in the Senate—if you’re there for a period of time, you understand what you believe better, you understand how to get things done better. You’re able to prioritize what you want to do, even though you’re drawn into a lot of different tensions. So you have more of a handle in terms of what you’re doing professionally. Tied into this was a good deal of personal anxiety as well with what was happening to my family and other issues of that period.

Young

It could make you feel kind of helpless in this situation, when they turn their backs on you and start doing that. That’s why I say it must have been very discouraging.

Kennedy

And in a very disciplined—they just knew exactly how to—I’ve been in the Army, and they had a coordination and a discipline that the Marines would have envied. They’d all turn their back, they’d all listen to their people, they’d all be responsive, they’d all fall in line. They all knew how to get to me, and did it very well. It wasn’t hard for them because they saw it—I mean I had some appreciation of how they viewed this. I’m sure you know that my children were going to private schools at this time. I’d gone to private schools. My parents always thought that members of the family ought to go to public schools. They went and moved to Bronxville, New York, which had good public schools, and my brothers and sisters all went to public schools. My sisters went to convents but they also went to public schools for part of the time, and my older brother Joe [Kennedy] did and Jack did.

Young

So it was perhaps an upsurge of class antagonism?

Kennedy

I was such a target for all of the kinds of things that they.... The fact is, I understood it. I mean, at least I understood it. I didn’t like getting targeted and I knew what I believed in and what I thought was the right course, but I had a very clear awareness, a very clear understanding and a good deal of empathy because the white schools were bad and the black schools were bad. We were viewed as trying to do something about education and trying to find ways that we could deal with those issues, and this other—I can’t call it a diversion, but it wasn’t about trying to elevate poor white schools and poor black schools, it was this other factor and force about trying to—never to get to that point to talking about what are we going to do to really strengthen education, all of it. You could never get to that point, you couldn’t reach that because of the emotion that was involved in the question of busing.

Young

Did the emotion die down?

Kennedy

Well, it’s interesting because we had—as you go on through, obviously, the early ’70s.... Just before we talk about going down that—it’s interesting in education and how people viewed education. I was talking to Vicki about Carl Elliott, who got the first Profile in Courage Award as a Congressman, for the National Defense Education Act. The National Defense Education Act was from years ago when education was perceived as being civil rights, and the people who were anti-black all were against education. It’s very interesting.

You know, I was just looking over others that had won the profiles, and Charlie Weltner from Atlanta won it. That’s much later. The ’80s and ’90s and this fellow [Corkin] Cherubini from the Carolinas had taught—this was in the ’90s—in school districts in the South.

Now we come on into the early ’80s and President Reagan agreed that there would be no help and assistance to any of the schools that were going to try to deal with this issue. Then I believe he goes, or he supports, Bob Jones University, which was getting tax deductions to schools that weren’t willing to comply with the federal laws. And then finally in ’84, Garrity gives—we have a different school board, school committee in Boston, and a black had even gotten elected to it, and Garrity gives the planning back to the control of the school committee. Then in ’85 there are polls in Boston and black parents favoring the freedom of choice of schools was 74%, which is exactly what the whites were saying at the start of this whole process.

Young

Did any good come of it?

Kennedy

I think today, the Massachusetts schools are the best in the country in the 4th and 8th grade, under the NAVE [National Assessment of Vocational Education] test, and more progress has been made reducing the disparity between black and white in Boston than any other major city in the country, and generally in Massachusetts we’ve reduced the disparity more than any other state. I was looking at those NAVE tests yesterday in one of the newspapers, and we’re still at the very top. Our disparity between our state test, which is the national test, is very little and we still do the best on it. What happened was there was such focus on it in the Boston schools that subsequently, the enlightened business community came together and said, “We have to do something about our school systems.” This was Mark Roosevelt, who ran for Governor and got beaten badly, but he was very involved in this. They had a foundation, that was the business community, a fellow named [Craig T.] Ramey, who is still involved in education reform, and they passed legislation that altered and changed the disparities, not completely but in a very important way.

Young

State or nation?

Kennedy

State disparities. They got started on education reform in Boston before the No Child Left Behind, but having gotten started, with the No Child coming in after it, the results have been that we’ve done better than other places. I don’t think it’s any question that that turmoil took the next generation of business leaders and legislative leaders, black leaders, city leaders. Mayor [Thomas] Menino, who has been mayor now for ten years, when this Tom Payzant, who was Superintendent of Boston Public Schools and President Clinton’s Secretary of Education, Secretary [Richard] Riley, were looking for a different way. I mentioned this to Tom Menino, and he had already put in play an outreach program to get it. When we talked about who was the best educator, superintendent in the country, boom, he went and got him and kept him for seven years, and gave more help and support in terms of cities, Tom Payzant will tell you, than probably any mayor in the country. Menino had been a major figure in that. He was probably a city councilor, not even a city councilor, but he lived in those areas and those communities. They still live there, he still lives in the North End. I think the post Boston busing time—

Young

Post Garrity.

Kennedy

Post Garrity time.

Young

After it got out of the Fifth Courts.

Kennedy

They’ve given a lot of focus and attention. It isn’t that they haven’t still got a lot of problems up there, but they’ve done a lot better than most urban areas.

Young

So all those things that were missing the first time—

Kennedy

In that immediate post period, we had the usual amount of youth violence that took place up there. We had the Morning Star Baptist Church, where they were having a funeral and some kids came in during the funeral and killed other kids. Menino set up this group. Now we had the Lenny Zakims, these conciliators, people who were in the business, religious community who, with the mayor, developed what they called the Ten Point Coalition, which were black ministers, and the COPS [Community Oriented Policing Services] program, local police, the schools with the truant officers and the Superintendent of Schools, the District Attorneys, and we went for a period of 15 months without a youth homicide, 15 months. I mean, there’s 100 of them in Washington, D.C. already this year. It was unbelievable, and all of that was the residue. People just said we don’t ever want to go through this again. Boston’s still got a lot of problems, but we have this dinner that Vicki and I went to, which is called—the dinner where they have the new—

Mrs. Kennedy

It’s One Boston.

Kennedy

One Boston, and it’s a thousand people there, and they’re all the new immigrants who have begun to make it in Boston. It is spectacular. They’ve had it for several years, but it’s probably the only city in the country that’s got it, and it is extraordinary. There are people from every different culture, country and everything, and all doing very interesting things, and all interested in keeping Boston together. They understand that. We’re the only city in the country that has worked on that and done that. I think so much of that comes in the aftermath of what happened.

Young

And then a new generation.

Kennedy

A new generation that has come in there, people who want this thing to happen and to go on. They’ve been very clever. They’ve got the [Bill] Gates Foundation, they’ve developed an institute for training teachers, and now they’ve got teachers who are staying longer, twice, three times the national average, twice the academic achievement, going into underserved areas and things like that. They’ve really attempted to do some things. As I say, it’s certainly not out of the woods, but there’s a very deep desire never to go back.

Young

So you had a hand in all this?

Kennedy

Vicki would remember this. We had this marvelous basketball player, Russell.

Mrs. Kennedy

Bill Russell.

Kennedy

Bill Russell, who was a superstar, and he just won national championship after national championship. At the end of his career he left Boston, which is just about this period, the ’70s. We were with him the other day and he said, “What a difference in the life and the atmosphere in this city. It’s a big change.” This person was revered by black, white, every community. He was a superstar athlete, and he just said he felt this pressure, that he could never live here. He comes back now and says it’s a new city. You know, you certainly hope so.

Young

Some of those dark days, when you were so discouraged, in the ’70s it wasn’t—

Kennedy

Well, those dark days in the ’70s in Boston have been transferred to the dark days in this century on Iraq. [Laughter] But I know you’re right.

Young

Each set of dark days, so that whatever you could do in Washington had—there was something to work with here. There was a self-effort and Boston was redeeming itself, I guess.

Kennedy

There’s that. There’s a lot of effort, the development of Upward Bound, the programs that take whole classes of kids and tie in a college and a university to them. We’ve probably got 60 or 70% of our schools signed up for that program, that are tied into universities, trying to take the whole class. The organization Access. Any kid who graduates from Boston will get the help and assistance for tuition. There’s a lot of action and activity to reach out to children from the existing institutions. The institutions in Boston were completely isolated. I mean Mass General Hospital, during this period of time, the idea that they’d have an outreach program. You had children in Charlestown who were 12 years old and they’d have 12 cavities in their mouth. They’re half a mile away and they could never get treated at Mass General Hospital.

Today Mass General Hospital works with neighborhood health centers, they’ve got two or three of those. It works well for them because they get screening and it gets a lot of the other part. They’re out in these communities. The major hospitals are doing it. The universities are outreaching into these places and there’s much more recognition, and the leaders in these places understand it, which they never did. The private leaders of these communities understand it. As I say, this doesn’t mean it isn’t a problem.

Young

Where are the Louise Day Hicks of this era? Are they gone?

Kennedy

She has gone on to her reward.

Young

But those neighborhoods are not that different.

Kennedy

It’s very interesting, this fellow Jimmy Kelly, who was one of the leaders in this group. Bill Bulger was very sympathetic to this and Bill Bulger turned out to be a good supporter of mine. He’s moved on from president of the Senate, where he wanted—he had a different responsibility, to the University of Massachusetts, where he did very well, but he was interested in higher education; what could we do, how we could work with it. He had changed and altered his ways. He had indicated he was supporting me and I said, “Well, can you keep Jimmy Kelly quiet?” He said, “Is that all you want me to do?” I said yes, and he did it, he talked to Jim Kelly and told him to keep quiet and Jimmy Kelly did. Jimmy Kelly died, he had cancer. I sent him a note, I called and talked to his son. His son, I don’t think is going to be a supporter of mine, but he’s—

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

█ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █ █

Young

Were you given any grief in ’94 from the old crowd?

Kennedy

Well, only just at the polls, I mean at voting time we had a drop off. It was gradually in those neighborhoods.

Young

They went Reagan earlier.

Kennedy

They went Reagan. I haven’t looked in recent times, but we’ve done well. We’ve done well in the recent times. I haven’t looked at them.

Young

There was one other thing that you might want to comment on. The Racial Imbalance Act that was passed in 1965, and it became, is Boston going to obey that or is it not? That’s where the NAACP suits first began, for non-compliance with the state on the part of the Boston School Committee. The rule there was if any school is 50% black or white, that’s a dual school system, and it was prohibited by state laws. Did you have any particular thoughts about that way of approaching it back in 1965?

Kennedy

I remember this going through. I think it was drafted by Father [Robert] Drinan.

Young

It was.

Kennedy

It was an attempt to try and deal with the broader issue at the time. I have no real clear recollection of much about that. I can probably look through the files. I imagine I was sympathetic to whatever was being done to try and deal with the problem, but I have no real sense about the legislation.

Young

The other thing is Bob Bates’ notes to you, memos to you, include a reference to discussions with Kevin White and others about a federal troop presence during this really difficult period. Would National Guard or something help the situation in the schools? Was that ever really an option, because the federal executive didn’t have much of a presence here in this whole thing. Missing in action, I would say.

Kennedy

I think when we had the violence in the schools, there were real questions about security and about what you have to do to get troops, you obviously have to federalize. The National Guard. I think there was a sense with what was happening in the schools and the intensity of the viciousness of the groups on this about the range of different options in terms of security. The local police or the state police or whatever is going to be necessary, federal troops. It never went very far. There was no effort on our part to try and get this. I don’t think there was much of a sense that they would have probably gone that far, because you had President Reagan in there, and you had to have the feds prepared to nationalize, and he was at that point, coming out for less and less, and cutting off the money. The general atmosphere is let’s let them stew up there.

Young

Or let Boston burn.

Kennedy

Let Boston burn. So there wasn’t really much of a recognition that they were going to be doing an awful lot on that level.

Young

Do you have something that’s on your agenda?

Kennedy

No. I never talked to Arthur Garrity during any of this. Arthur Garrity graduated from Holy Cross. I’m not quite sure where he went to law school. He’s a very bright, very smart person. He was a great supporter of my brothers. He was out in Wisconsin during the Presidential primary, but he was probably separated in terms of the politics of it. I mean, the people who were out in Wisconsin, Polly Fitzgerald, who is out there now, just loved my brothers to death. She was so devoted as a political figure, and everybody who was up there, except Arthur. He was rather academic about this. He had a warm, Irish heart and emotion and support of it, but he was very controlled, very disciplined, and he never got associated as being a Kennedy figure, although he was very devoted. The only thing that I always felt—you know, he was appointed at the most difficult time in the city of Boston, and that was his whole life. He did some other things on the federal bench, but this was an immersion. I always empathized. He had two wonderful sons, whom we met subsequently, but I never spoke with him during the period, talked to him about that.

Young

No. Well, that wouldn’t have been—

Kennedy

No. Nor should you or could you, but we never had any contact. But I always felt that he was thinking that here is President Kennedy trying to deal with this, and we have to make sure that we’re going to try and get this thing right for Boston. I always thought he acted under the best of motives, with a very limited hand, about what he was going to be able to do. You could always wonder how this could have been done differently, what could have been done differently at that time. But I think as all of us know, when you have the kind of city that we were talking about and had the lack of housing opportunities to move, the lack of job opportunities, the other chances of moving out or moving into new kinds of climates and atmosphere and conditions, it was just stuck in this.

Young

Stuck and it was—

Kennedy

It was a very limited range.

Young

—already polarized, or the fat was already in the fire and it was like a hot potato.

Kennedy

It was just too late to think that some other things could have been worked through. Just a final point. In the consideration of Supreme Court nominees, they looked back. People have been listening to the questioning of [John] Roberts and [Samuel] Alito, about Brown v. Board of Education and the role of Justice [Earl] Warren and the problems of race in the country. I spent a lot of time questioning them on not just the issues of busing, but whole questions of how we’re going to deal with the problem. You look over their answers that they gave at this hearing, and Roberts had been in the Justice Department and he had been guiding the Justice Department for the changes in the Voting Rights Act, to have an intent test instead of an effects test, which would have changed the force of the law—and then he was against. When we had discrimination at the universities, the case there, they said that as long as it’s not discrimination in financial aid to students—the case is on the tip of my tongue, but I can’t remember it now.

Young

Was it Grove City?

Kennedy

The Grove City case. But he prepared the administration’s position on that, which we had to overturn, and then he went to the Solicitor General’s office and he was mischievous on this. They had the Federal Communications Commission talking about a broader participation for minorities and he entered for the Solicitor General on the opposite side from the agency. So he had—And then we have Alito, who gave very similar answers to Roberts, and we went to this case, that is the Seattle case, that all it is is voluntary busing—local communities saying that we want to have our children grow up with schools with children of different races. This is the Seattle case, and we sat in on the oral argument to see how they are going to rule on this, which is going to be all voluntary. This is going to be an interesting postscript.

Young

It will be.

Kennedy

Where we were at this period of time. I’ve already got the article written about how they answered the questions, where they came from and how we anticipate, because we went over there for the argument in the Seattle case, and listened to him in the Supreme Court, and listened to them both question. I walked out of there and I said, “I know just where those two votes are going.” But I have followed this whole process and have seen this whole issue and listened to them testify before the Judiciary Committee, and seen how they waffled around on that part, and now how they’re going to come back to their true colors, which is predictable. It’s more a reflection about how we’re going to select our Supreme Court Justices or other justices in the future, rather than having anything to do with busing, but it is busing, it is voluntary, it’s local community trying to recognize their sense as parents that they’ve got good schools in all of these places. The schools themselves are very good, and they want their children to grow up in an experience with diversity in it, and they’re doing it voluntarily and to see how the Supreme Court comes down.

Young

But somebody’s complaining.

Kennedy

But somebody’s complaining. So that’s going to be an interesting bit of—

Young

There’s an education project at Harvard, called the Civil Rights Project. Gary Orfield runs it and they’ve kept track of the changing demographics and how it’s affecting the schools. They’ve come up with some surprising comments—surprising to me at least—and that is that there is a trend now in many urban areas toward more segregated schools, but it’s a function of the demographics. Some of the most integrated schools systems are the larger ones that include rural areas in the South—they include greater diversity because the territory is much larger. The common problem, I guess, and you’re aware of this I’m sure, is that when you get into that situation, the inner city schools are smaller districts, and this is what happened in New York. They used to be districts, now they’re smaller. The smaller you get, the more they are embedded in an ethnic community. You know the blacks in these schools socialize with other blacks from the ghetto and that their exposure to—you know, they’re turning out kids who don’t know how to do an interview. They don’t know how to behave in an interview when they apply for a job. So the problem, in a sense, is still with us.

Kennedy

Yes, that’s true. I think just the final point to wrap up. One of the real transitions that we saw during this period of time is the change and attitude towards the courts. As one who believed in and still does, as an institutionalist, the importance of institutions. We saw the beginning of the fracturing of the respect for the executive branch, in the wake of the Vietnam War. We weren’t being told the truth on this. We saw it with the courts, to some extent on this issue of race, I think to some extent on Roe v. Wade, to some extent on Miranda, and a considerable extent because we had Presidents who talked about “strict constructionist,” meaning, “I’m going to appoint people who will agree with me rather than people who follow the law.” So they gave the green light to people who were on the other side. So you had the undermining both of the executive and the court systems during this whole period, in a way I think is probably unique historically. Maybe there are other examples historically. But I think that that has to be altered and changed if we are expecting our institutions to be able to deal with the modern challenges of our time.