About this episode

April 29, 2016

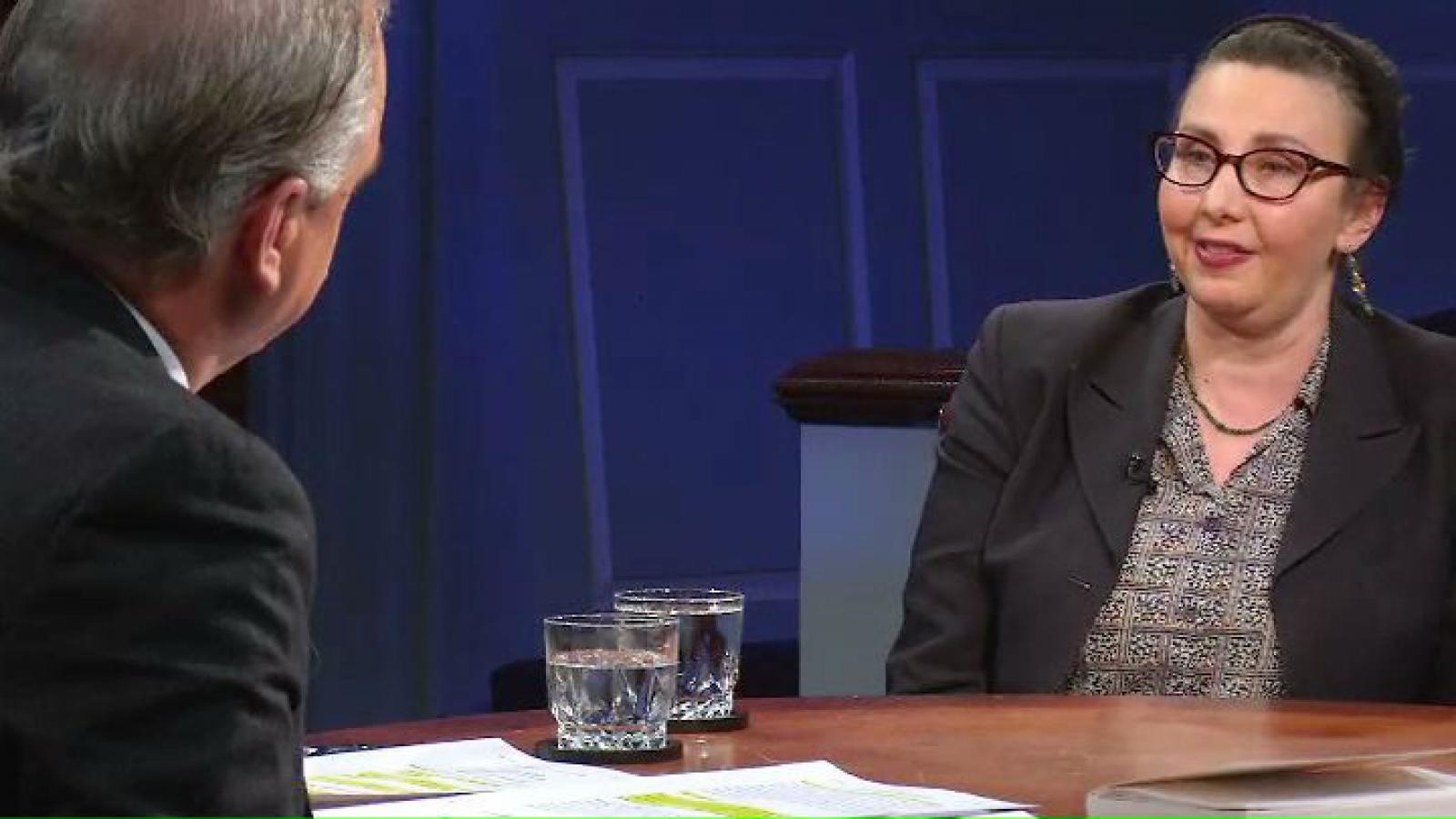

Carla Power

A journalist specializing in Muslim societies, global social issues and culture, Carla Power is the author of "If the Oceans Were Ink: An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Quran." The book is an account of a year in intense study with the traditional Islamic scholar Sheikh Mohammad Akram Nadwi.

Religion

A journey to the heart of the Quran

Transcript

0:41 Doug Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. Two hundred thirty years ago, in 1786, the Virginia state assembly enacted a law, written and proposed by Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, called the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. It would become the basis for the First Amendment to the U.S.

FACTOID: Virginia Statute for religious freedom passed in 1786

Constitution which articulates perhaps the most universally shared value among all Americans, and is likely our society's single most distinct and important contribution to all human intellectual accomplishment. And indeed, if there is any basis for the notion of American exceptionalism, it is in our First Amendment and our commitment to the free expression of differing faiths and ideas of all kinds. What many Americans don’t realize, however, is that Jefferson wrote, at the time, that the American concept of religious freedom specifically protected not just the many variations of Christianity predominant in our new republic, but also Jews, Hindus, and using an archaic term for what is now the second most widely followed faith in the world: “Mahomedans” Muslims. Followers of the prophet Mohammed. A group that collectively refers to itself as “the umma.”So the concept of tolerance for Islam is as fundamental to our most basic national values, and as rooted in our history, as any other dimension of American democracy. That has not been widely understood since the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the long war that followed. For many, a great gulf has opened between western culture and the world of Islam. In response to terrorists and political figures in the Middle East citing the Quran—Islam’s Holy Scriptures—to justify violence and the repression of women and others, many Americans have been swept up in kind of “Islamophobia.” New terms have been invented—like “Islamo Fascim.” Many Americans have concluded that Islam and terrorism are inextricably entwined. A leading presidential candidate proposes that no more Muslims be allowed to enter the United States. The Quran is demonized. But what exactly does it say? Does it authorize the oppression of women; execution for non-believers; mass murder and hatred? Joining us today is Carla Power, a writer for TIME magazine and specialist in Muslim societies and culture. She is the author of the wide-acclaimed book, If The Oceans Were Ink: An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Quran. It is a moving account of a year spent seeking to deeply understand Islam, through an intense study with an Islamic scholar, Sheikh Mohammad Akram Nadwi. And was a finalist for this year’s National Book Award. Thank you for being here.

FACTOID: The Question: How can the west better understand Islam?

Carla Power: Thank you for having me.

3:28 Blackmon: This is really book that is about a personal journey of yours. It’s about, in some respects, it reflects on, on uh, our national politics and the giant national dialogue that’s going on in the country, but it’s also about something that goes back to the very in the fundamentals of American democracy. Why exactly did you, an American non-believer, not a Muslim, decide that you needed to pursue this journey and write this book?

Power: Um, well, as you say, there was a very personal reason, um, I’d grown up half in the Middle West, in St. Louis and, and some of the time in the Middle East and Central Asia. When I was writing news stories I felt I was sort of shunted into strongman or oppressed woman categories and, um, and bombs and burkas basically. Um, and then when I went on and tried to write feature stories, um, I would do things like, you know, covering, you know, halal products or Muslim punk bands or Pakistani, Sufi shrines or so on. And I’d find myself, um, kind of going from they’re different from us to they’re exactly like us. It reminded me of, sort of, um, the magazines you see when you go to the supermarket and you see celebrities who were sipping their lattes or have they’re kids, you know, they’re just like us sort of thing, and I never really delved far into the Muslim world view. I have never in all those years been asked to read the Quran. I have never been asked to cite it as, um, as a way of looking at a Muslim light. So I really wanted to dig down and see how a Muslim world view was animated by it. And I did it also, at a time when we’re very polarized when we just don’t sit down a listen to folks who have, um, different points of view from ourselves. So I saw it more than just pursuing a personal interest in Islam.

5:40 Blackmon: Were you imagining this as something that, uh, a personal question you needed to answer for yourself. Was it to write a book or to serve an audience or was it really a, an intense need on your part to understand Islam?

Power: It, it was both. I mean I had written about Muslims as people who did things for years, who built political parties or who, um, who had unveiled debates or who went on Haj, and um, I realized, I was looking at it from the outside and for me it was a very personal thing, but obviously, um, as someone who has thought about this for a long time, I find it incredibly painful how simplistic the discourse is, and the idea behind was to try to complicate, um, these, these neat little compartment we have, is somebody a moderate or radical? Is somebody a fundamentalist or, uh, a progressive?

6:47 Blackmon: Well the, the title of the book, If The Oceans Were Ink, which is a poetic, very elegant title, also a little unclear what it means. But that comes from scripture from the Quran that you quote in the book, and part of that scripture is, “if the ocean were ink writing the words of my lord, the ocean would be exhausted before the words of my lord would be exhausted,” That’s a scripture that we could, we could tell most any American. Uh, we could quote that scripture to them and say that it was from the Bible, and they would almost certainly say that sounds reasonable. What does that tell us?

Power: Um, that I think there’s a real misconception of what the Quran is about. There’s a tendency, um, to see it as a series of rules, a series of very strict rules that we read about in the headlines. And instead it’s a very subtle, nuanced, um, I don’t even want to call it a book anymore because it’s so capacious and, um, you know, it, it’s, reading it is the work of a lifetime. Um, but, uh, I think, um, the scriptures are often closer than one might surmise, and again, I mean this particular verse that you quoted, um, I picked as a secular person looking for, um, looking to bolster my beliefs in pluralism and diversity.

8:21 Blackmon: What were some of the discoveries that you made for yourself and for all of us, in terms of either clichés or stereotypes that seem to be predominant, that you discovered something different or that, or things that you discovered for yourself to be different from your own assumptions, I assume that there were some of those as well. But walk us through some of that, what is it that we’ve learned over the course of your journey?

Power: Well the, the first thing I learned, I mean, I had assumed, I sort of went to this Sheikh and said, “I’m totaling embarrassed, but I’ve never read the Quran.”

FACTOID: Quran is Islam’s central text, as revealed to Muhammad

And his first response is “Oh don’t worry, most Muslims don’t either,” you know, but when I talked to him about Madrasas, about religious seminaries and very high level ones. He’s like, “look, the Quran really isn’t at the center even of tremendously prestigious Madrasas.

The Quran is not at the center of their curriculum. They’re much more interested in Law or Arabic Rhetoric or so on. You know in one way it’s incredibly central to Muslim lives. It is threaded through it. You hear it, you see it on walls and so on. But he mourns that not enough people are going back to it. Um, that was the first thing. The second thing. Was what does an Islamic scholar look like. We have images of a bearded, a bearded man. And one of the things that drew me to the Sheikh besides our longstanding friendship was the fact that he has sort of backed into being an accidental feminist.

FACTOID: Sheikh Nadwi is scholar at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies

Ah, by having uncovered a heretofore all but ignored history of um women scholars in Islam dating back. And these you know one gets fed over and over again that media stereotype of the oppressed and muffled woman. And he has gone back and he has he came to me one day and he said you know, I’m working on something you’ll be interested in. There’s I’m going to do a slim pamphlet on Muslim women scholars of Hadith. Or of the words and deeds of the prophet Mohammed. He he like you know I figure it will be like 30 or 40 names you know.

FACTOID: Muhammad, founder of Islamic faith, was born in Mecca in 570

It will be a little book. Ten years later he had uncovered over 9,000 women scholars stretching back to the days of Mohammad. And these are women who are issuing fatwas. They’re riding on horseback over across Arabia giving lecture tours lecturing by the prophets’ tomb. So it reallyto me now stretches to 40 volumes although it is as yet unpublished.

FACTOID: ‘Fatwa’ is an opinion or ruling given on an aspect of Islamic Law

11:10 Blackmon: Sort of, yeah, dramatically different picture of women and the world of Islam.

Power: Exactly, Exactly

11:15 Blackmon: But what about what the Quran says today or what we perceive, a, the, the predominant views that Muslim society today are of women within their societies. I mean I think that’s one of our, one of our primary assumptions is that this is a world in which women suffer a tremendous amount of oppression and have to wear the burka (Power: Right) and girls aren’t allowed to go to school, etc. etc.

Power: Right, right. Oh, well I’m I mean that, that you know Islam puts a tremendous amount, I mean the prophet Muhammad, was like, “You know, you’ve got to get out and get educated. Seek, seek knowledge unto wherever you can find it.” Um, and that value of education was for men and women, a, both. Um, in-in during early Islamic times, you know, men and women were both in the mosque together, all sorts of things that, um, we, we, we contemporary Muslim women can’t do, um, or in many, many parts of the, the Muslim world, culture has meant that they have been excluded from, um, whether it’s the Taliban, shutting down girls’ schools, or or women not feeling comfortable in mosques around in, in many cultures. Um, When-when you go back to the original sources, um its, a, they they were there in seventh century Arabia, a, um you know, pretty much right alongside the men in many, many venues. One of the things that’s, that’s happening, and-and we only we hear about what the negative side is, we are living in a time of tremendous intellectual ferment for Islam. Um, people are rethinking their faith, um, and that has led to really, really scary, um, fundamentalist movements, but it has also lead to some very progressive um looks at, at how to reconcile, um, the, the essence, um, the spiritual essence of Islam with the 21st century. So you have a very strong Muslim feminist movement, that is increasingly, um becoming vocal, trying to change Muslim personal laws that are very um, that, that can be very, you know, very restrictive in terms of divorce, and, and, and child rearing. Going through and changing these laws, um, and, and women are going back to the Quran and questioning. Um and as, as literacy spreads, as people migrate, as they have, more access, to um, um to information on their own part. Um, we read about the scary stuff that’s coming out, but at same time, there are these progressive, and a, um and other sorts of rethinkings that don’t get covered.

13:56 Blackmon: I think if we tried to boil down to the-the simplest-most overgeneralized, um, descriptions of major faiths, we would say that Christianity ultimately comes down to a concept of forgiveness, a, a, and that Hinduism comes down to a concept of, a, of and effort, and Buddhism as well, efforts to achieve some sort of a balance with a larger, sort of universal deity. Uum what does, based on your journey, wh-what does Islam come down to, what is its fundamental?

Power: Um, at the beginning of my journey I would’ve said justice. I learned in my grade school courses that justice was sort of the cornerstone of Islam in the way that love is sort of the cornerstone of Christianity. Um, and, and that striving and seeking justice was-was something that both the Quran, and-and the prophet um, a, strove for. I think, I think now I would come away with the notion of um, um of submission. Of um submission to a greater power than, than, than yourself to god and when, when I, I can see that there is love and forgiveness in there, um much more than I think Islam gets, gets recognized for. In the, a, what I call the Quran in 25 words, the first, the first verse of the Quran, god as merciful, is mentioned twice. Um, and you don’t, you don’t necessarily read a lot about that these days of-of mercy um, but um, I was, I was amazed that a, a rather kinder and gentler, um , faith than often than, than, a, gets portrayed in the headlines.

15:51 Blackmon: The Sheikh your, your, a, your mentor in all this, a, as progressive as he is in many respects within the context of a, Muslim scholars, a, he, a, also still can only go so far, a, as far as women today, even though he, a, has unearthed this remarkable history of women scholars, a, and so some of the limitations on the lifestyle of women he would still ascribe to a certainly can’t go, a, to where American society has gone to in terms of homosexuality (Power: Right.) a, and in fact, his views on that would be more consonant with the leadership in North Carolina and Mississippi right now, a, than, a, than most folks in, or many people in America. But so, what does, what does that tell us? Is it that, is that a reflection of Islam or is that, a, a reflection of the societies, the conservative societies within which Islam is most predominant?

Power: I get very nervous about saying something is absolutely intrinsic to Islam. Um, I think one of the major tasks that Muslims today are doing is because so many more of them can read, because so many more of them have a global view, they are going back and trying to tease out what is culture and what is, is Islam itself. Um, so I, I, I was struck over and over again at how tolerant, um, Islam is of other faiths, um, of-of diversity in various ways, but yes, um, the sheikh, you know, um, he, I would, I would sort of have this kind of switchback effect of going from listening to him sound like he was heading up a feminist collective in Vermont to-to sounding like a patriarch, um, and I think the danger is when we try to think of Christianity as a default position, or we try to think of Islam as on a spectrum, you can find people who give tremendously literalistic readings of the Quran who are then, you know, very pro-women. You can find Sufis who are, um, very conservative, Sufis or mystics who are very conservative. So, um, I think I think mainstream contemporary Islam, um, is is, is not, is not looking for gay theologies, and, and that’s in part, um, maybe something to come, maybe it won’t be.

FACTOID: Sufism refers to beliefs of Ascetic, mystical Islamic sect

18:28 Blackmon: It’s interesting to me that, uh, if we look at these two faiths, that, going back in time for Christianity is a bad thing. That’s where we find all the bad stuff. But when we start talking about Islam, the tendency is to say well actually, but what you see today isn’t really what it is, the really cool stuff is what was going on back then. And so, does that suggest that Christianity is on a forward path, and that Islam is on a backward path?

Power: Hmm, um, I mean I think everybody wants to root themselves in the founding myths. I mean much as we all harken back to the Constitution, you know there is, um, real sense that um you go back to the Quran and Hadith if you’re if you’re in the mainstream tradition. And early Islamic history is much more than the past for, um, for practicing Muslims.

FACTOID: Hadith refers to the teachings and traditions of Muhammad

Um, after all, the notion of the perfect man is Muhammad, and many many pioused Muslims see him as, um, a, a, a blueprint, a model for-for what they will do; that doesn’t necessarily mean they will engage in absolutely everything he did, but, but that is seen, Islam is very rooted in history, no other prophet in history has been as carefully noted and detailed as-as-as Muhammad. Um, but at the same time, to make it, I, I would not want to suggest that it is a static, closed, simple harkening back to Seventh Century. I mean I think the challenge for many, many Muslims is how, how do you animate the values of, of that, that Muhammad and the Quran contain, and how do you make them relevant to 21st Century life, so, I, I, I think, um, it’s an inspiration, I don’t, I, I, I think nobody would-would quarrel with the idea that the many Muslim countries are in a terrible, terrible mess, now, um, I certainly would not say that is Islam, um, it-it’s, um, you know, from Napoleon on, it’s, they’ve been dealing with lots of other stuff.

20:44 Blackmon: We seem to come back over and over again in these sorts of, uh, expirations, to the notion that, okay there are these extremists this world who have taken faith to somewhat perverse ends, uh, there are also a lot of conservatives in this faith who are actually fundamentally good people, but they also hold some specific views that, perhaps on women or on, uh, homosexuality, or on other things that are objectionable by Western standards, and then there are these much more progressive voices. We certainly can’t tar the other, the two groups with the terrible deeds of the, the really violent group. That’s the very forgiving approach to this I think, and I think that seems like that’s where you ended up, you concluded. At the same time, uh, you know, the day after 9/11 when, uh, a Wall Street Journal reporter I was working with made his way to the home of, uh, Mohamed Atta, the leader of the hijackers, and talked to his very reasonable, middle class, professional, Egyptian father (Power: I’ve been to that home, I know it well, yes, yeah), we were there within 24 hours (Power: okay you beat me, you beat me by…), uh the wonder of the Wall Street Journal in those days, um, no more, uh. You know, this was someone who was supposed to be coming from that tolerant element of Muslim society, and yet the son had just been involved in this incredibly terrible thing, uh, and the father a) couldn’t believe that it was his son, and then until the father died some years later, uh, could never really condemn what, what his son had done. Um, and so it does seem that while there is this more progressive element, this less dangerous and radical element of, of Muslim society, at the same time, they also can’t quite seem to get to what we would really feel was a moderate and um, uh, reciprocal kind of tolerance.

FACTOID: Mohamed Atta was an Egyptian hijacker and leader of 9/11 attacks

Power: I would disagree. I mean I think I think one of the things that 9/11 did was it pushed many, many Muslims much more out, out into the world. I mean I say it was sort of like the best of times and the worst of times.

22:46 Blackmon: But I want to make sure we’re clear on you’re saying 9/11 pushed them or the American response to 9/11 pushed them to a more radical place?

Power: Probably, probably the latter. You’re absolutely right. Okay. Um, why are we talking about this in Islamic terms? Why do we assume that this is the faith at action? Why is it not? For example, the fact that America’s propped up dictators in the regime who, who are very happy to choke off any other sort of, of political discourse, um, that for example in Egypt, you know the Muslim Brotherhood really, for, for many rational peaceful people was kind of the only opposition for a long time under Mubarak. Um, I think why aren’t we talking about the post-colonial situation where, where, uh, people are, are recovering from, you know, over 200 years of domination um by, by western and foreign powers and have, have grasped at the only thing that they see as authentically theirs. So I think religion gets blamed for a lot of, of, of geopolitics and, and, and people just stop at “it’s about Islam.”

FACTOID: Hosni Mubarak was Egyptian president from 1981 to 2011

One of the reasons is so strong is that, and and was able to spread so quickly was this pretty simple belief, you know, you submit and um, you do, you know, five or six things that you’re supposed to do and as long as it didn’t interfere with that you can go on doing your, you know, your animist beliefs in Africa or your, your South Asian syncretic beliefs with Hinduism, and so I think understanding the local context that various Muslim manifestations are coming out of is really important. We have to break down um this notion that there is a, a, you know the very destructive notion that there is a class of, clash of civilizations. It’s not true. There, there are clashes with particular localized contacts and particular political beefs.

24:53 Blackmon: Well thank you for writing a, important and elegant book.

Power: Thank you

Blackmon: Carla Power. The book is If The Oceans Were Ink: An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Quran. We hope the viewers of American Forum now watching this program on nearly 300 public television channels across the U.S., will keep this conversation going. That’s what the American Forum is about. Every week. Dialogue. Discussion. Being aware of the lessons of history and respectful of the views of our fellow citizens, even the ones we misunderstand or disagree with. And we invite you to directly join the conversation with American Forum on the Miller Center Facebook page or by following us on Twitter @douglasblackmon or @americanforumTV. I’m Doug Blackmon. See you next week.