About this episode

September 23, 2016

Nicole Hemmer

In this episode, we explore the connection between media and politics. Our guest, Miller Center historian Nicole Hemmer, suggests that we may fundamentally misunderstand the current revolution in political media—and that we definitely misunderstand its origins. Hemmer’s new book, "Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics," maps out how media entrepreneurs began building the modern conservative movement following World War II.

Political Parties and Movements

How did our politics get so crazy?

Transcript

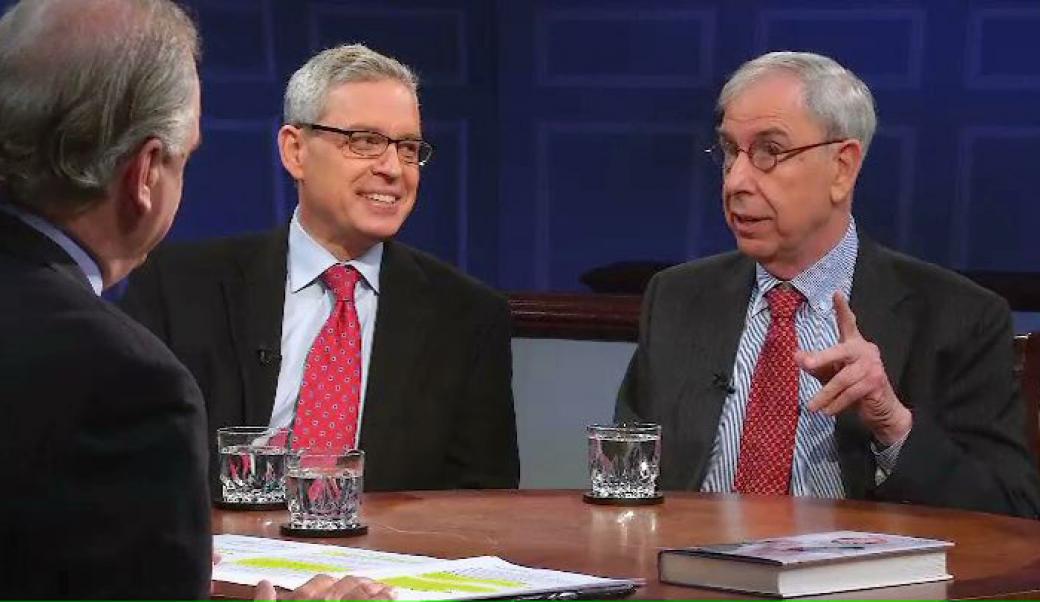

Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. One of the great paradoxes of our national political life these days centers on the role and vitality of “the media.” We constantly hear that news organizations are less influential than ever, that they are economically doomed, that fewer and fewer citizens get news from traditional sources such as newspapers and nightly broadcasts, and that political candidates can simply “bypass” the media and speak directly to the people. Journalists like me, who made a living with ink and paper for 30 years, look like dinosaurs. Yet at the same time, we are awash in what feels like more political media than ever. Fox News has been raking in cash and trouncing CNN and MSNBC for years. The scandal-obsessed, Internet-based Drudge Report has been getting more than a billion page views per month of late. Rupert Murdoch's Wall Street Journal has two million readers a day, the most of any U.S. newspaper, and almost twice as many as that little old also-ran in the number two spot, The New York Times. The legendary Washington Post, it barely registers on that radar screen. How is all that possible? Our guest in this episode of American Forum suggests we may fundamentally misunderstand the nature of the current revolution in political media—and that we definitely have misunderstood its origins. Historian Nicole Hemmer has just come out with a new book, Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics, in which she maps out how in the aftermath of World War II, media entrepreneurs began building the modern conservative movement.

FACTOID: The Question: Who really started the conservative movement?

She argues, essentially, that right leaning media came first and launched the breakaway political activism that has profoundly reshaped Republican politics, given rise to Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan, Fox News, Rush Limbaugh, and so much of the conservative political revolution of the past four decades, And now, in 2016 has given the nation Donald Trump. Hemmer is an assistant professor in Presidential Studies here at the Miller Center, a contributing editor to U.S. News & World Report, and co-host of "Past Present," a history podcast launched in October 2015. Thank you for being here.

Nicole Hemmer: Thanks for having me.

3:08 Blackmon: Take it back to the beginning the story that you tell of when, what we now would call conservative media. When that began. What some would disparagingly call right wing media but maybe that’s not. But go back in time in terms of intellectual DNA tell us who Sean Hannity’s great granddaddy is.

Hemmer: Sean Hannity great granddad. Well the story really starts in the 1940s and the 1950s. If you want sort of a start date, it’s in 1940 and 1941 with the America First Committee. This was a group of people who were against American intervention in World War II and there were a lot of conservatives among them who believed that it just wasn’t the U.S.’s responsibility to get involved in Europe’s war. And they found themselves pushed out. They saw that neither the Democratic nor the Republican Party agreed with them. They found themselves pushed out of major newspapers and magazines and disparaged and they didn’t call this liberal media bias but they did call it bias. They did call it a blackout. And that experience of not having their views heard of having all sorts of social and economic and political capital, but not being able to do anything with it that sense of frustration is what ends up feeding this new right wing media in the aftermath of World War II when the same frustrations resurface in the fight against communism and the extension of the New Deal and all of these policies that they deeply disagreed with, but that the two parties and most of the major media endorsed.

4:42 Blackmon: And so these folks who have been involved in America First who then kind of have to go out of sight or change their mind during the period of World War II. It’s also even a little amazing to even imagine that, that it was possible to be politically rehabilitated after World War II if you had been; at least the way remembers those times now, to have opposed fighting the Nazis and Imperial Japan one would’ve imaged that would’ve been a faction of American life that would have no political future after the war, but it does. There’s a reformation and there are specific people, some of whose we may be faintly familiar with, but many of them not. So how does that happen after World War II?

Hemmer: So it does happen in the early year immediately after World War II. When the same folks who were involved with America First regroup, and they want to advance their politics in this post war world, and so people like Felix Morley, start a little weekly newsletter called Human Events. Human Events is still around today but it gets its start in 1944 and it doesn’t have many subscribers at first. It is very much on the outskirts of politics, because there is still this revisionist history about the war at the heart of it. But it slowly begins to morph into a newsletter that covers domestic and foreign policy and that’s conservative. And they bring on a young man in 1945 named Henry Regnery, and Regnery may be a name that viewers are familiar with because Regnery in 1947, he breaks off from Human Events and he starts his own conservative publishing company. Regnery Publishing, it isn’t very profitable in the period between the 1940s and the 1970s but it would become so. It’s the name behind many of the bestsellers you see in bookstores today.

Blackmon: Yeah it’s now Regnery Press, right?

Hemmer: That’s right.

6:25 Blackmon: And yeah, almost every polemical conservative book that you, but then somewhat philosophical or political science high likelihood that it’s coming from Regnery Press today even though he’s long gone, right?

Hemmer: That’s right. He’s long gone but the press is still around and it’s now turning a profit. Something he never saw.

6:46 Blackmon: Yeah I imagine so. But so there’s Regnery, there’s Clarence Manion, William Rusher, who publishes the National Review, but you also describe something, a visual anecdote. You describe a gathering in 1953 in room 2233 in the Lincoln Building in New York City. Who was at that and why is it such an important gathering of people?

FACTOID: Clarence Manion hosted early conservative radio show 1954–1979

Hemmer: So this was an important gathering because in 1953 Henry Regnery calls together all these different conservative media figures. Its ’53 so Manion’s radio program doesn’t start until ’54. National Review isn’t launched until 1955. But you do have conservative writers and conservative broadcasters who are beginning to come together. And the point of the meeting was twofold. One to sort of note that here were these people who had so much power and so little political influence, and they had to do something about that. And Regnery said the reason we don’t have the influence we should have is because we don’t control the means of communication. So on the one hand it was about trying to coordinate some more conservative media but it was also about trying to make some end roads politically to begin to cultivate new candidates, to build new parties, so that conservatives would have a political home from which they could advance their policies and they could begin to win elections and make real political change.

8:10 Blackmon: It’s ’53, but at this stage they’re not so much licking their wounds from what happened in World War II but more from the rise in Dwight Eisenhower. Give us the context as to why this is also an anti-Eisenhower beginning.

Hemmer: Absolutely. So 1952 is a critical turning point for the birth of conservative media, because so many of the people who would go on to found the Manion Forum who would found National Review they were big Robert Taft supporters. Taft the conservative senator from Ohio, and he was seen as the next in line for the Republican nomination and what happens this upstart who had never been a political figure before who had no political experience.

FACTOID: National Review founded in 1955 by writer William F. Buckley, Jr.

Blackmon: Wow, wait a minute, an upstart who had never been a political figure before, wait I’m sorry

[laughter]

Hemmer: but was one of the biggest celebrities of the early 1950s

Blackmon: Wow Wow.[more laughter]

Hemmer: This political upstart comes out of nowhere and he becomes the Republican nominee. And for conservatives there was a belief right from the start that that nomination had been stolen. They constantly pushed back against Eisenhower. And the very first edition, the very first issue of the National Review they have all these long anti Eisenhower screeds and the specially point to that ’52 nomination as the moment when they knew that they weren’t going to be accepted as a major political force in the United States. Clarence Manion who started the Manion Forum, He hung on in 1952 even though he was a big Taft supporter he went out and he backed Eisenhower. He dutifully, dutifully fell in line and he was even apart of the Eisenhower administration. But unlike other conservatives who were a part of the administration they quickly found themselves butting heads with these more moderate Republicans, and then they eventually in Manion’s case get fired and then they go off and start their own organizations. And he got fired because he was supporting this little known amendment called the Bricker Amendment.

FACTOID: Bricker Amendment tried to limit power of president to sign treaties

It was sort of a national sovereignty resolution and the people who supported the Bricker Amendment said look you’re an effective speaker who have this story of being booted out of the Eisenhower administration for sticking to your guns. We want to give you some air time to spread your message so maybe we can rally up support for the Bricker Amendment across the country. So they bought him 13 weeks of airtime, where he would appear not three hours a day like Rush Limbaugh or Sean Hannity, but 15 minutes every week to not just talk about the Bricker Amendment but to talk about conservatism. And he was so successful at it that those 13 weeks which started in October of 1954 became 25 years.

10:43 Blackmon: And there’s a discussion at one point about the possibility of creating a new party the American Party, as it’s called, and that all of this is going to be an alternative to what they perceive as being a choice between the New Deal Democrats and the New Deal Republicans, as you write or quote someone saying. But that idea that the Republicans are actually new dealers just as the Democrats are so they’re trying to create this third way, but the, which it never quite works. I mean that idea of the conditional party never quite. Why was that and what was the plan at that time?

Hemmer: So they certainly were going to try to launch a third party in 1956 the American Party was T. Coleman Andrews at its head, they were going to try to affect a realignment. They wanted to grab conservatives from the south who were Democrats and conservatives from the north who were Republicans and bring them together in a new party. And there were a lot of different schemes for how this was going to work, but every time they tried to put it into practice it didn’t really. And the reason that they stopped pending their hopes on third party politics, at least for a while, was Barry Goldwater. So in the late 1950’s Clarence Manion meets Barry Goldwater. He has him on his show. It’s the first national radio appearance for Goldwater, and he sees in him a potential fusion figure. He’s someone who can appeal to Democrats in the south because of his opposition to civil rights, but he’s also someone who can appeal to western libertarians and northern Bob Taft supporters. So he is seen as this fusion figure. And so Manion is like how do we make Barry Goldwater a household name? And not just a household name but the face of conservatism across the nation. And his idea is to have Goldwater write a manifesto. Goldwater was little busy so he lined up a ghostwriter. He couldn’t find a publisher for the book so he ends up self-publishing it through his own little publishing company that he has. And that book Conscience of a Conservative, not only becomes a best seller, but it makes Barry Goldwater a nationally known conservative figure and the best hope for conservatives not to have a third party candidate, because Goldwater wasn’t interested in that, but to become the Republican nominee which he is in 1964.

12:57 Blackmon: One would of might have said Goldwater’s collapse would’ve snuffed out this whole phenomenon but it didn’t.

FACTOID: Goldwater lost 1964 election to Johnson, winning only 39% of vote

Hemmer: In fact, many people didn’t say that at the time. So the New York Times had an editorial the next day that it was essentially like oh thank goodness conservatism is done, and we can now go on with a newer rational more forward politics in both parties. For conservatives, Goldwater was an important moment, but it wasn’t the end game. They had done something no one thought they could do. They had managed to win the nomination of a major party with someone whose beliefs were often seen as on the fringes of American politics. What the Goldwater loss taught them though was that they hadn’t done enough to reach out beyond just conservatives. That in many ways in building this conservative media movement over the1950s and early 1960s they had been coalescing their own power, but they had largely been talking to themselves. And so they take up so many new initiatives in 1965 and in the late 1960s to begin to reach out, not to conservatives, because they already have conservatives, but to reach out to what they call the apathetic; the average American who maybe doesn’t really think a lot about politics or about these ideas, and doesn’t understand what’s at stake. Umm, so they do a lot of things trying to distribute programs so that they reach college students as opposed simply going out in conservative communities. They actually help launch the American Conservative Union. It was media activist who formed the American Conservative Union after the 1964 loss. This was a moment when they wanted to take all of their expertise and ideas but use them more effectively for politics. To use them for effective political organizing that has direct electoral implications. And that was a big change after 1964.

14:46 Blackmon: So if somehow it were possibly to have Senator Goldwater sitting at the table with us, what do you think he would say to the proposition that he in effect was a creation of media rather then that his emergence and his thinking and his influence created a rich thing for media to cover? How would he react to your proposition that he’s a product of these media forces?

Hemmer: Well Barry Goldwater was a man who did not like to be handled, so this idea that he was a product of anyone other than himself I think he would probably not agree strongly with. But fortunately he’s not here so we can look back at the historical record and see the ways in which conservatives co-opted in many ways Barry Goldwater, and brought him into the 1964 election kicking and screaming. He didn’t want to be running for office through much of 1963 and they said they were just gonna draft him, and that’s what the end up doing. And they end up creating a campaign that runs alongside his campaign. So by the time he gets the nomination, he’s not interested in hanging out with conservatives anymore. He really closes himself off. He hires his Arizona mafia, all of his close friends to run his campaign. So conservative media simply develop an alternative campaign running alongside the Goldwater campaign, which really was the first media driven campaign of the modern era where they we’re defining the race through their own media to their audiences as a race between a conservative and a liberal, a chance for a choice.

16:23 Blackmon: And so how do we get from these figures you’re talking about, I don’t believe any of them end up as early investors in Fox News, or you know allies of Rupert Murdoch, so how do we get from them to the current conservative media world that surrounds us?

FACTOID: Fox News founded in 1996 by media mogul Rupert Murdoch

Hemmer: Well so by the mid to late 1970s many of these media enterprises that I write about, they were kind of running out of steam. They didn’t have a lot of money. It was really a tumultuous time within conservatism in the Republican Party and the nation at large, and so they’re largely out of power by the 1970s. And then you have the Reagan administration and there isn’t a strong conservative media operating during the Reagan administration.

FACTOID: In 1980, Reagan won over 50% of popular vote to Carter’s 41%

You have human events and national review still there, but they’re sort of riding the wave. They’re not creating the wave. Where you get a second generation of conservative media is with the rise of Rush Limbaugh in 1988 when he goes national, and he’s really coming off of this Reagan crest. The connection between the two, even though they’re very different, is that what Rush Limbaugh and Fox News inherited was this conservative identity that had been crafted over 50 years, where conservatives as part of being conservative sought out conservative media sources. Rejected mainstream media as being biased, and looked for media that was conservative. And so in many ways there was an audience waiting, and that audience was built by this first generation.

17:54 Blackmon: Is there anything bad about this?

Hemmer: Well it depends on who you ask. I do think that what we’ve seen in the last several years in particular. There’s been a lot of attention paid to the role of conservative media in politics. And one of the problems has been the incredibly close relationship between conservative media and the Republican Party in a way that was very different from this first generation. This first generation worked very closely with Republican politicians, but they didn’t really have veto power in the way that they seem to have in the 2000s and the early 20-teens, this idea that you didn’t wanna cross Rush Limbaugh. You didn’t wanna cross Fox News because you were gonna pay a real political price for it, and that has brought the Republican Party further to the right.

FACTOID: Fox News evening viewership averages 1.8 million viewers

So depending on where you stand on right wing politics is whether that’s a good thing or not. I do think that if there’s a downside to it more broadly it’s that this criticism of media as being biased has helped to feed a distrust in media and a fragmentation of media that have left Americans without a common ground.

FACTOID: CNN’s evening viewership rose by 38% in summer 2016

A common news source, a common place of conversation, or even a common set of agreed upon facts. And that then creates a political debate that doesn’t work because you’re not debating on the same grounds. You’re talking past one another, and if there’s an outcome of that I think it’s at least in part this idea that our current obstructionist politics comes out of that inability to talk to one another, agree upon a certain set of things, and then move forward based on that agreement.

Hemmer: Certainly the attacks on the establishment, and the justification for tearing down an establishment that courses through conservatism and conservative media from the 1940s on is very much present in the politics of Trump, as is this idea that the media are biased, and they’re not telling you the truth.

FACTOID: 58% of Republicans, 55% of Democrats view other party very unfavorably

That they’re forcing everyone to be politically correct, and not actually telling you how things are. That suspicion, and some conspiracism as well, that has been present in conservatism over the past 70 years. Those aren’t always dominant in the conservative movement, or conservative media, but they have been there and they’re sort of becoming focused upon and condensed under Trump.

20:25 Blackmon: And we also are in this time now where I think it’s true, that more so than ever before, just because of social media and the ease that this can happen. But that we now are in a time in which it’s not just an argument over what’s a common set of facts, but in which there’s this wholesale invention of false facts, that surrounds political activity. It’s astonishing to me how much material is out there that is abjectly false. I mean the Birther claim is the most fundamental of those.

FACTOID: Trump popularized false “birther” myth that Obama not U.S. citizen

But even the idea that a, not this year, but that you could have a medal of honor winner’s, the veracity of a medal of honor winner’s story of their service uh in war, be questioned, uh, openly questioned on the basis of clearly false claims. And so there has to be an audience for all of this. You know, it doesn’t work unless there’s an audience, uh, and that’s the American people. And so I mean has something changed with the American people? Was it that at one time we had some, our parents or grandparents had a demand for truth and a better sense for what’s bs and what’s not? And now we don’t have that? Or is there something else?

Hemmer: Well I think that it’s a combination of things. First of all, trust in any sort of author, has disappeared. And that is somewhat new and so people, I hear this a lot, I hear it from my hairdresser, I hear it from people that I talk to when I talk to them about media. They’re so frustrated, because they don’t know what to believe. They haven’t been taught the skills that they need in order to wade through so much inaccurate information. We are in a new media environment that allows for false information to gain quite a bit of traction. But also, you don’t have an authority that you can turn to and say “tell me what’s true.” And I think that that is part of the reason why conservative media has become so much more important in the last 10 to 15 years, is because if you have that ideological agreement, you can say to a Sean Hannity, “I trust you, just tell me what’s true because I can’t make sense of all of this.” And is that entirely new? I mean people have always sort of looked to authorities in order to make sense of the world. Um I think what is troubling and troubling for democracy about this is that without any sense of what is real and what is not, I think that you lack the informed citizenry that you need in order to, um, create an effective and useful politics.

22:58 Blackmon: So I want to put you on the spot, is conservative media as you’ve been describing it here. Is it less reliable, than what, in terms of facts, than mainstream media, what would be conventionally called mainstream media, uh, is that the case and then finally, last thought, um, is this a call to action of some sort? Should something be different, or are you just observing a set of realities? But is there something that should happen? But first that, are you saying that conservative media flat-out is just less reliable and less factual than conventional media?

Hemmer: I’m saying that it has become less reliable. I think that at the start, it was bringing to the table stories and ideas that were being overlooked by conventional media. And that was actually bringing more good, useful information to the table. I think that as, conservative media grew bigger and more insular, there was less of a feedback mechanism, to make sure that what they were saying was comporting with reality, and that disconnect has been recognized not just by liberals, but by conservatives as well. Charlie Sykes, who is a, um, conservative radio show host in Wisconsin, has talked about this, he says “we need to have a reckoning, because we’ve divorced conservatives from the feedback loop with what’s going on in the world.” Is it a call to action? The only reason I might say it’s not a call to action is because I don’t know how you fix this. I mean I think it’s something we continue to talk about, but if you don’t have someone who can be an authority and say “now wait a second, that’s not true and you shouldn’t believe it.” I don’t know how you fix the problem without someone who can draw those lines.

Blackmon: Niki Hemmer, thanks for being here. The book is Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics. We hope you’ll keep this conversation going, about our media, our politics, and most of all how citizens across the entire spectrum of political perspectives can engage each other, be civil in our dialogue, listen to one another, and maybe get a few things done. In these tumultuous days, let’s believe in each other, and in our Democracy. That’s the first requirement, of patriotism. We also hope you’ll join our conversation at the Miller Center Facebook page, or by following us on Twitter @americanforumTV. You can also tweet me directly @douglasblackmon or today’s guest Niki Hemmer @pastpunditry. To watch other episodes of American Forum, download audio podcasts or read transcripts of these conversations. visit us at millercenter.org/americanforum. I’m Doug Blackmon. See you next week.