Divisions at the 1968 DNC

August 1968: Delegates at the 1968 Democratic National Committee in Chicago decide on their presidential nominee

The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago was a reflection of that consequential year in United States history.

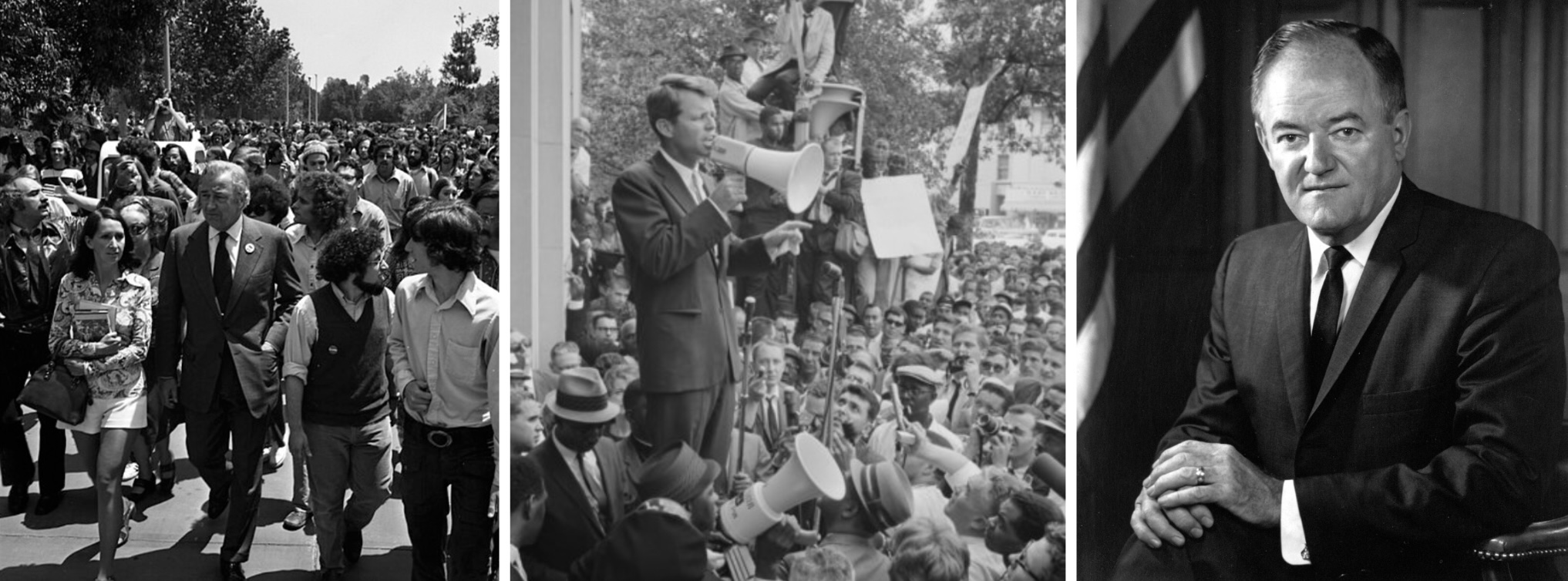

After increased fighting in Vietnam after January’s Tet Offensive and growing public protest of the war, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration was in peril. On the Sunday evening of March 31, he shocked the nation by announcing he would not seek re-election, nor accept his party’s nomination, for the presidency. Although LBJ and the democratic establishment selected Vice President Hubert Humphrey as their choice for the nomination, candidates had already been challenging the incumbent president prior to his announcement, including Senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy. After winning the crucial California primary on June 4, Senator Kennedy was shot and killed, just as civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. had been that April. These acts of violence at home and abroad led to outrage and protests, especially among young people and the emerging counterculture. No protests of the 1960s would be as widely televised in living rooms across the country as those during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

The Democratic Party was deeply divided prior to the convention. In 1968, candidates running for the presidency were not required to compete in primaries, and very few states even held them. However, Senator Robert Kennedy’s campaign reached a turning point in June 1968 by winning the influential California primary. That night, Kennedy was assassinated and died two days later, giving the lead back to Humphrey going into the convention. His only other main challenger was Eugene McCarthy, whose views against the war in Vietnam were drastically different from the incumbent administration’s, giving him a younger demographic of supporters.

At the last minute, South Dakota Senator George McGovern also entered the race. Despite the fact that the Vietnam War was unpopular and divisive within the Democratic Party, Vice President Hubert Humphrey was in a strong position going into the convention.

“A Very Disgusting Performance”

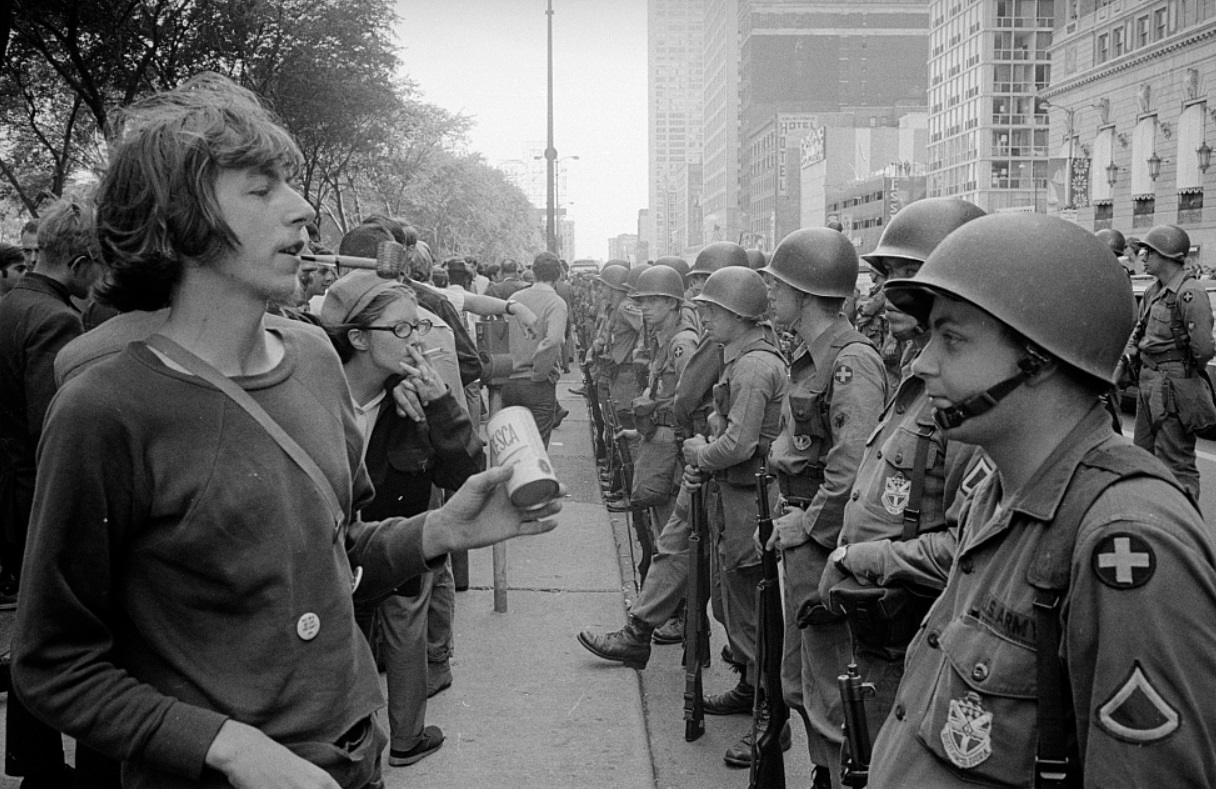

On the evening of August 28, protests intensified and the American public became aware of the severity of the situation as the scenes played out on television. The morning after violent clashes between demonstrators and Chicago police, President Johnson spoke with Attorney General W. Ramsey Clark. LBJ emphasizes not only the problems with the clashes themselves, but also the fact that they were broadcast on television. As many argued that the protestors should not have been given such a platform, this event is additionally considered to be a turning point in accusing the news media of liberal bias.

Date: August 29, 1968

Time: 11:29 a.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, W. Ramsey Clark

Tape Number: WH6808-04-13334

The protests also contributed to a growing feeling of distrust of establishments during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Though predating the Watergate scandal, a lack of transparency over the Johnson Administration’s policies in Vietnam made the protests at the convention one of the most significant manifestations of these anxieties.

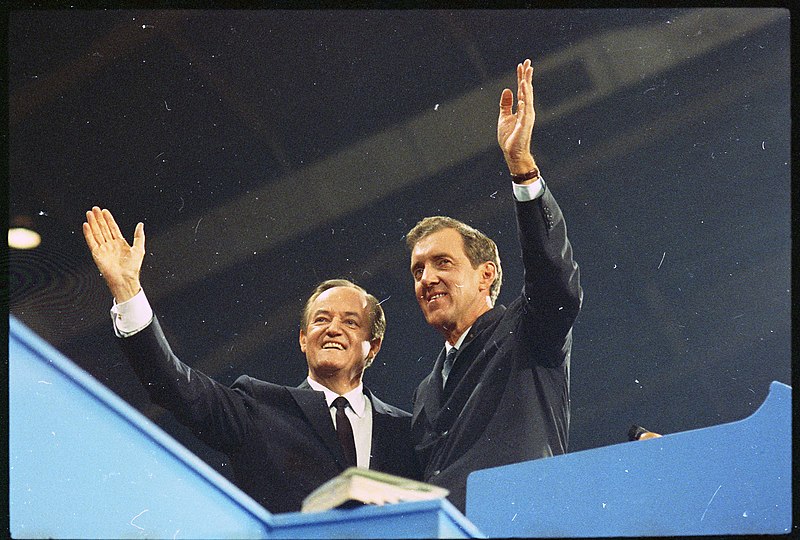

“The Vice Presidency is an Impossible Job”

Despite the devastating scenes outside the convention hall, the divided Democratic Party managed to nominate Hubert Humphrey on the first ballot. Nevertheless, some of the violence did make its way into the convention hall. When delegates voted on a referendum pertaining to Vietnam policy, clashes between those for and against changing the party’s stance over the war broke out on the floor. When delegates were informed of the police confrontation happening outside the convention, anger broke out inside the walls of the convention. In the end, Senator McGovern gained 146 delegate votes, and Senator McCarthy received 601 votes, but the eventual nominee received 1759 votes. Upon receiving the nomination, Vice President Humphrey called President Johnson on who to select for his running mate.

Date: August 29, 1968

Time: 10:41 a.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert H. Humphrey Jr.

Tape Number: WH6808-04-13330-13331

“I’d Go With Muskie”

A few hours later, Humphrey, now the Democratic nominee, called LBJ to inform him he had chosen Maine Senator Edmund Muskie, who he figured would be loyal. When Humphrey asked the president if he would be attending the convention that night, LBJ declined, emphasizing that his presence at the DNC would only add more chaos.

Date: August 29, 1968

Time: 4:16 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert H. Humphrey Jr.

Tape Number: WH6808-05-13341

Whereas LBJ enjoyed a unified party in 1964, specifically because of the public still mourning JFK’s death, the president’s party was going through seismic changes four years later. Along with the issue of Vietnam, President Johnson’s signing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act found Southern Democrats in a party they didn’t recognize. Even with LBJ’s significant achievements from his Great Society agenda, the divisions displayed inside and outside the 1968 DNC revealed rifts in the Democratic Party that had been present since the New Deal and continue to fracture the party today.

One of the few positives from the convention were the reforms it demanded. Following the convention, the McGovern-Fraser reforms removed the power of selecting candidates from party elites and resulted in an increased number of primaries in each state. However, this also allowed for a rise in populism in American politics, allowing 2016 candidates like Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump to be competitive despite not having the support of party leaders.

Although eventual consensus over a candidate was reached at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Vice President Humphrey would not become the president-elect in November. Humphrey’s ties to LBJ’s unpopular war policies favored Former Vice President Richard Nixon, who secured 301 electoral votes and 43.4% of the popular vote. Humphrey received a relatively competitive 42.7% of the popular vote, but independent candidate and Alabama Governor George Wallace also influenced the race, receiving 13.5% of the vote. Regardless of the candidates, the protests and the violent scenes televised from the convention in Chicago left voters with a sense that the Democratic Party was fractured and disorganized. The event also produced images of some of the most violent and significant protests of the 1960s, a decade full of disagreement, revolution, and change.