Rutherford B. Hayes: Campaigns and Elections

The Campaign and Election of 1876

By 1875, the Republican Party was in trouble. A severe economic depression followed the Panic of 1873, and scandals in the Grant administration had tarnished the party's reputation. Falling crop prices and rising unemployment also worried the Republicans. Ohio Republicans turned to Hayes, their best vote-getter, to run against the incumbent Democratic governor. Once again, Hayes won a close race, with 5,544 votes out of almost 600,000 cast, and was immediately spoken of as a contender for the 1876 Republican presidential nomination.

As the favorite son of Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes had much in his favor. Both regular and reform Republicans liked him. He was a war hero, had supported Radical Reconstruction legislation, and championed African American suffrage. He also came from a large swing state. His reputation for integrity was excellent, and his support of bipartisan boards of state institutions endeared him to reformers. Hayes ultimately, though, realized that his simple "availability" was his greatest strength. Distasteful to no one, he was the second choice among the supporters of the other leading candidates. Nevertheless, Hayes insisted on a united Ohio delegation—and at the same time did nothing to lessen his availability.

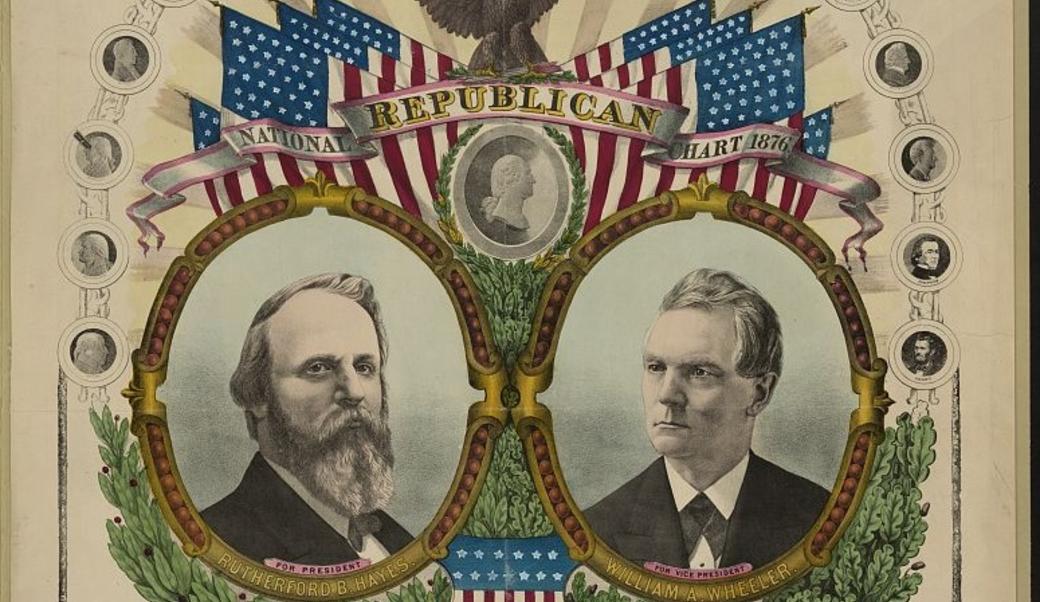

Moreover, the 1876 Republican convention was in Cincinnati, which teemed with Hayes supporters. "Availability" did work for Hayes. James G. Blaine, the frontrunner and the favorite of partisan Republicans, was tarnished by allegations of corruption; Oliver P. Morton, the favorite of Radicals, was in ill health; Benjamin H. Bristow, the favorite of reformers, was anathema to Grant; and Roscoe Conkling, the quintessential spoils politician, was unacceptable to reformers and to Blaine. In the end, none of these candidates could muster the votes of the majority of the convention. By the fifth ballot, Hayes had picked up votes; by the seventh, he had clinched the nomination.

The Republicans faced a very difficult campaign. The Democratic candidate, New York governor Samuel Jones Tilden, had strong reform credentials. He had helped bust the infamous Tweed Ring, a corrupt group of Democrats that had been running New York City for years, and then smashed the state's corrupt canal ring. In addition, Tilden was a superb political organizer, and the Democrats in the South were certain to use violence to keep black and white Republicans from voting. Finally, the Republicans had been in power for a long time and were hurt by scandals. Meanwhile, hard times gripped the economy. There was strong sentiment for throwing the ruling party out.

In that era, custom frowned upon overt campaigning by the presidential candidate. Beyond publishing an acceptance letter, candidates were not supposed to demean themselves by making such public appearances—the office should seek the man. Not only were candidates mute, national committees were virtually powerless. State and local party organizations, usually headed by senators and congressmen, conducted presidential campaigns. In his acceptance letter, Hayes called for a reform of the civil service and pledged to serve only one term, lest patronage be used to secure his reelection. (Indeed, he later supported a constitutional amendment limiting the President to a single six-year term.) He also backed the resumption of specie payments (return to the gold standard) as scheduled for 1879. Most importantly, Hayes was a supporter of honest and capable local government in the South, as long as it respected the constitutional rights of all citizens.

The Disputed Election of 1876

The 1876 presidential election proved to be the longest, closest, most hostile, and most controversial—at least up to that time—in the history of the United States. Hayes knew it would be close and predicted that if he were defeated it would be "by crime—by bribery, & repeating [voters]" in the North and by "violence and intimidation" in the South. The issues seemed so acute that the rate of voting among whites was the highest in the nation’s history. And, for the first time, voters throughout the nation all cast their ballots on the same day—the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Early returns on the telegraph from both Ohio and New York showed Tilden in the lead, and Hayes went to bed convinced he had lost.

The next day, however, Hayes learned that he had carried the California, Oregon, and Nevada; the added Republican electoral votes of the brand-new state of Colorado (admitted on August 1) also proved crucial. Both parties claimed to have carried Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Tilden had a plurality of 250,000 in the popular vote and was one electoral vote shy of the majority needed to win the presidency. But if Hayes carried Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, whose official votes would be determined by Republican-controlled "returning," or canvassing, boards, he would win the presidency by one electoral vote. In those states, as well as in the rest of the South, intimidation and violence kept black voters from the polls. With good reason, Republicans asserted that had their votes been counted, Hayes would have carried the three disputed states as well as other southern states.

Citing intimidation, and greased by bribery, the returning election boards in the disputed states invalidated enough Democratic votes for Hayes and the Republican Party to emerge victorious. A further complication arose in Oregon: Hayes carried the state, but one of his electors was a federal office holder and therefore could not be an elector. He resigned his job after the election, but the Democratic governor of that state certified a Democratic elector in his place.

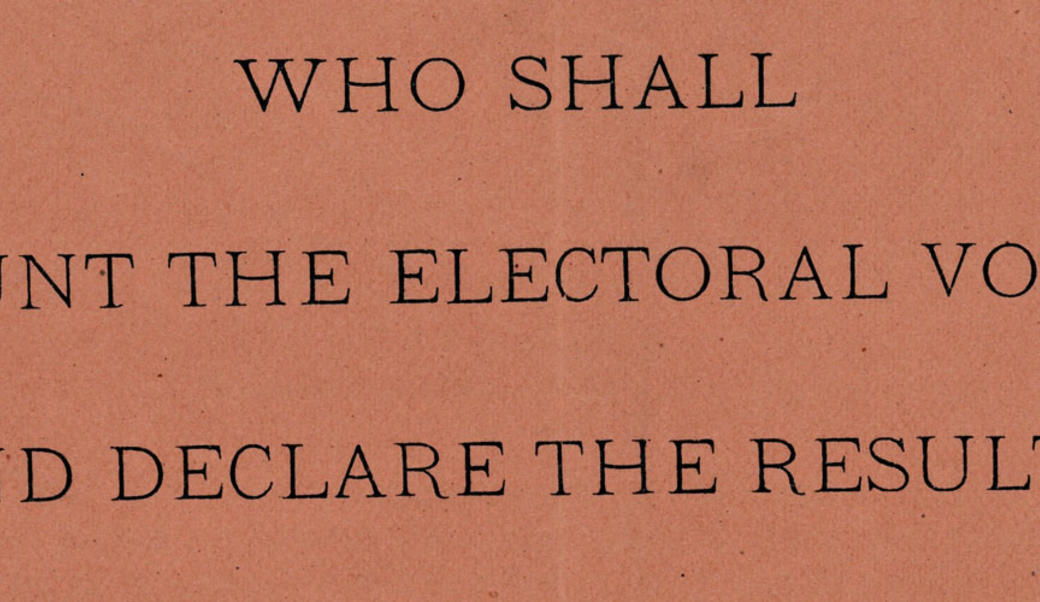

When electors met in state capitals to vote for President on December 6, 1876, separate Republican and Democratic electors met in Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Oregon, and cast conflicting votes. These were forwarded to Washington to be counted by the presiding officer of the Senate, Republican Thomas W. Ferry, in the presence of both houses of Congress. Ardent Republicans claimed that Ferry had the right to decide which votes to count, but Democrats insisted that the joint session with its Democratic majority must decide.

Congress resolved this impasse with a compromise (incidentally, the only important compromise in the disputed election). The Electoral Commission Act passed in January 1877. The Act established a commission of five senators (three Republicans, two Democrats), five representatives (three Democrats, two Republicans), and five Supreme Court justices (two Republicans, two Democrats, and one political independent, Justice David Davis) that would decide which votes to count and thus resolve the election.

Initially, Hayes did not approve of the Electoral Commission Act since it meant giving up on electoral "certainty." But after Congress passed the bill, he realized it would enhance the legitimacy of the ultimate victor. Supreme Court Justice Davis, however, disqualified himself after a monumental miscalculation by Tilden's corrupt nephew, Colonel William T. Pelton, who assumed that electing Davis as senator from Illinois with Democratic votes would purchase his support for Tilden on the Electoral Commission. Davis was replaced by a Republican, Joseph P. Bradley, giving Hayes's party an 8:7 edge. Despite Bradley’s independent streak, the commission awarded Hayes the disputed states, with the vote proceeding along strict party lines.

After the Electoral Commission awarded Louisiana to Hayes (which Tilden unofficially carried by 6,300 votes but where the Republican returning board threw out 15,000 votes of which 13,000 were Democratic), the Democrats knew that Hayes would win. Combining frustration and calculation, they then delayed the counting of electoral votes with frequent adjournments and filibusters which threatened to plunge the nation into chaos by leaving it with no President on inauguration day, March 4.

Those who calculated (as distinct from those who were irrationally angry) hoped to secure concessions from politicians close to Hayes. Among their objectives were the removal of the handful of troops that protected the remaining Republican state governments in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Columbia, South Carolina; a federal subsidy for powerful railroad magnate Tom Scott’s Texas & Pacific Railroad; and cabinet appointments for pre-war Whigs (the latter was accompanied with hints that if so rewarded, white southerners would be attracted to the Republican Party).

That southern Democrats and Hayes's friends negotiated is a virtual certainty, but that they struck any "deal," "bargain," or compromise that offered anything beyond what Hayes promised to do in his letter of acceptance is doubtful. Hayes, whose rhetoric was overtly opposed to the idea of “a white man’s government,” and his representatives insisted that they would withdraw the troops only when the civil and voting rights of black and white Republicans were respected. It is also clear that the southern negotiators had little or no control over the irrational filibusterers that prolonged the count. Samuel J. Randall, the Democratic Speaker of the House, realizing that creating chaos would backfire on the Democrats, finally ruled the filibusterers out of order and forced the completion of the count in the early hours of March 2, 1877. With 185 votes to Tilden's 184, Hayes was declared the winner two days before he became President.

This distasteful victory left widespread hard feelings. Tilden had actually received a quarter million more popular votes than Hayes. This fact, coupled with the partisan work of the Commission, convinced Democrats that the recent political disgraces in Washington were far from over. The sneering Democratic press—and even his bitter Republican rival Roscoe Conkling--dubbed Hayes "Rutherfraud" and "His Fraudulency." No presidential election would be so controversial until the 2000 contest between George W. Bush and Al Gore. There were so many parallels between the two elections—including the over-sized significance of the electoral count in Florida—that historians, as well as public figures such as sitting Chief Justice of the United States William Rehnquist in a book titled Centennial Crisis, spilled considerable ink on comparing 1876 and 2000.