Condolences: Personal and public

Martha Washington's public role continued after her husband's death—much to her chagrin

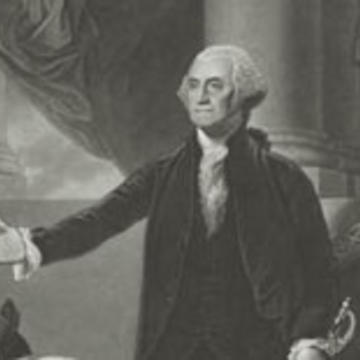

Celebrity deaths rarely go unnoticed. And, to Martha’s chagrin, George Washington’s was no exception. Martha Washington stood by her husband’s side when he became commander in chief of the Continental Army and later the first president of the newly formed United States. Reluctantly, she continued her public role after his death on Dec. 14, 1799. A review of the condolence letters Martha received shows how often her public and private lives continued to intertwine in the later years of her life.

These letters came from all around the nation and Europe. Correspondents ranged from friends and acquaintances (including Alexander Hamilton, Henry Knox, and the Marquis de Lafayette) to statesmen, orators, authors, organizations, schools, and even strangers. Most discussed General Washington and his national importance and offered sympathy and advice. In total, Martha received approximately 55 condolence letters. Tobias Lear, George's former secretary and a close family friend, assisted Martha in responding to them by composing drafts or copies of acknowledgement replies, or by writing entirely on her behalf.

One of the earliest letters arrived from a family friend, Elizabeth Willing Powel, dated Dec. 24, 1799. Martha and Elizabeth, a Philadelphia socialite who was heavily interested in the politics of the day, had a longstanding friendship. Naturally, her letter displays a friendly tone of familiarity: “I presume your Grand Children are with you, and doubt not that they will afford you every consolation that existing Circumstances will admit. Present me affectionately and sympathetically to them they also have lost a protecting affectionate Connection, and I have lost a much valued Friend.”1 On the same day, Maria S. Ross, a veteran’s wife in Lancaster, Pa., sent a letter expressing her sympathies. Maria, “[t]ho a stranger in person and Name,” wrote a note that was just as heartfelt as Elizabeth’s: “It is none but those that feel, know how to administer balsam to the wound, His virtues in this Sublunary world, have insured him blessedness above.”2

His virtues in this Sublunary world, have insured him blessedness above.

Several of these letters requested small gifts, to which Martha acquiesced. Organizations such as the Masonic Lodge of Massachusetts and a “society of Females” in Providence requested that locks of George’s hair be sent to memorialize him; Martha allowed it in both cases. In another instance, then-congressman Peleg Wadsworth asked for a lock of George’s hair on behalf of his young daughter. Martha again permitted it, moved by the young woman’s wish. Giving locks of hair was common in the eighteenth century; George’s hair and signature became treasured tokens after his death. These cases indeed reflect George’s significant public role and what he meant to people. However, as a whole, it underscores Martha’s personal strength in dealing with her husband’s death and in taking on the additional burden of the nation’s grief.

The letters from John and Abigail Adams especially highlight the intersection of national affairs and the Washingtons’ private life. Abigail’s note of Dec. 25, 1799, reveals her long friendship with Martha, established during George Washington’s presidency. It conveys a personal touch of grief and affection: “I intreat, Madam, that you would permit a Heart deeply penetrated with your Loss, and Sharing personally in your Grief, to mingle with you the Tears which flow for the much Loved partner of all your joys and Sorrow’s.”3 John’s letter of Dec. 27, on the other hand, carries a different tone. President Adams immediately begins by relaying to Martha Congress’s request to bury George’s remains under a “marble monument to be erected in the Capitol” in Washington, D.C., in commemoration of the late president’s political and military achievements.4

Though George’s will and testament instructed that he be buried at Mount Vernon (where he ultimately was laid to rest), Martha acquiesced to President Adams and Congress’s request in her reply of Dec. 31, 1799: “Taught by the great Example which I have so long had before me never to oppose my private wishes to the public will—I must consent to the request made by congress—which you have had the goodness to transmit to me—and in doing this I need not—I cannot say what a sacrifice of individual feeling I make to a sence of public duty.”5

I cannot say what a sacrifice of individual feeling I make to a sence of public duty.

Multiple occasions in Martha’s life similarly demanded her adaptability and willingness to forsake a private life at Mount Vernon for the public’s interest. She visited General Washington at each winter encampment every year during the American Revolution. She was inoculated against smallpox, enabling her to stay at winter camps during the war. She resided and hosted salons with George in New York and Philadelphia during his presidency. And, for most of her life, she traveled along poorly built roads and to further distances than she ever had before.

Other individuals noted Martha’s renewed grief in response to President Adams’s request. In his letter to Adams, Tobias Lear recognized Martha’s emotions: “After a severe struggle, Mrs Washington has yielded to the request made by Congress. . . . Having passed upwards of forty years with the Partner of her Heart, it required more than common Fortitude to consent to an act which, possibly, might deprive her of almost the only consolation she has had since his decease—namely—that her Remains would be deposited in the same Tomb with his.”6 Abigail also described how Martha “was so melted into Sorrow that she was two hours getting through the Letter of the presidents, and one which I wrote her. . .you will see by her replie to the president the struggle she had to bring her mind to relinquish the only consolatary Idea She had left her, that of mingleing her Ashes with his.”7 Martha anticipated she and her husband would be buried together. The idea of being separated from him in such a way was painful to her, but she nevertheless conceded to Congress's request.

This particular collection of letters, diverse in correspondents and contents, reveals the constant overlap of private and public affairs that Martha experienced throughout her lifetime. The Adams’ letters especially demonstrate a tangled web of friendship and civic duty that required Martha to continue to play a role in public matters. Death, in some cases seen as an end, only prompted another round of public demand for Martha Washington.

1. “Elizabeth Willing Powel to MW, Dec. 24, 1799,” in Joseph E. Fields, ed., “Worthy Partner:” The Papers of Martha Washington (Westport, Ct., 1994), 325-26. ↩

2. Maria S. Ross to MW, Dec. 24, 1799, Mount Vernon: Peter Family Archives. ↩

3. Abigail Adams to MW, Dec. 25, 1799, ibid. ↩

4. “John Adams to MW, Dec. 27, 1799,” in Fields, “Worthy Partner,” 327-28. ↩

5. “MW to John Adams, Dec. 31, 1799,” in Fields, “Worthy Partner,” 332-33. ↩

6. Tobias Lear to John Adams, Jan. 1, 1800, Mount Vernon. ↩

7. Abigail Adams to Cotton Tufts, Jan. 9, 1800, Pierpont Morgan Library: Literary and Historical Manuscripts. ↩