Sorry, Virginia, you can’t revive the Equal Rights Amendment

Legal expert Saikrishna Prakash contends that the Constitution mandates a new process to ratify the ERA

Read the full story at the Los Angeles Times

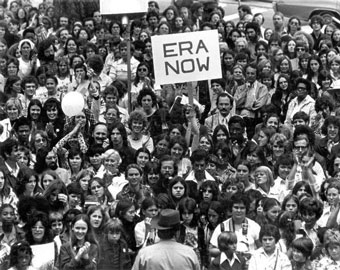

In January, when a new Democratic majority takes over in Virginia, the Commonwealth likely will become the 38th state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment. At that point, the proposal will cross the three-quarters threshold for inclusion in the Constitution, almost a half century after the amendment went to the states. Understandably, the ERA’s supporters will be jubilant. Though I endorse the ERA, I can’t join them. Virginia’s ratification will be stillborn and the Equal Rights Amendment will still be dead. Under a proper reading of the Constitution, it perished decades ago.

When Congress sent the ERA to the states in 1972, the accompanying resolution provided that that the amendment would be valid only if ratified by three-fourths of the states in a little over seven years. As that expiration date drew near, Congress extended it an additional three years. The extension was controversial because it changed the terms of the ratification period midstream, and because it was not passed with a two-thirds majority in both chambers, as the 1972 resolution had been. To add to the uncertainty, by the time of the extension, a handful of states had voted to rescind their ratifications, a move as legally murky as monkeying with the deadline.

[B]ecause the second deadline came and went without a sufficient number of states on board, . . . the ERA was deemed finished.

Neither controversy came to a head, however, because the second deadline came and went without a sufficient number of states on board, and the ERA was deemed finished. The historian and former chairwoman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Mary Frances Barry pronounced the amendment a “failure”; another supporter said it had “lost.” Everyone supposed that proposed amendments did not last forever, that they couldn’t be acted upon by the states decades or centuries after Congress voted. When Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then a law professor, argued to extend the ERA ratification deadline, she admitted that it was “implicit” that state ratifications of “a proposed constitutional amendment occur within some reasonable time” after congressional proposal.

That conventional and sensible view, one voiced across centuries, got called into doubt by a unicorn event, a mad rush to ratify the Congressional Pay Proposal, now styled the 27th Amendment. The proposal first passed in Congress in 1789, along with the Bill of Rights. It limits self-dealing by requiring that congressional pay increases can go into effect only after the next election. When it failed to win enough state ratifications in the late 18th century, it was kaput. Nonetheless, because no time limit had been included in the original proposal, some tried to resuscitate the moribund amendment in the 1980s and early 1990s. States eager to be seen as putting some limit on Washington paychecks piled on, and no one in Congress was brave enough to risk the bad political optics of opposing the popular proposal.

When confronted with these belated ratifications of a stale proposal, the Office of Legal Counsel of the Department of Justice opined that proposed amendments could be ratified over centuries. But it did a rather poor job of countering the old orthodoxy or reconciling its views with contrary Supreme Court pronouncements. Indeed, the OLC essentially ignored its own conflicting opinion from the 1970s, in which it had joined then-professor Ginsburg in concluding that proposed amendments necessarily come with an expiration date. In other words, it was an OLC flip-flop of epic proportions.

No one thinks that Congress can pass laws ‘inter-generationally’

To be sure, the Constitution says nothing directly about time frames for lawmaking or amendment passage, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t speak at all on the topic. It assumes and implies a great deal. No one thinks that Congress can pass laws “inter-generationally,” with the House voting for a bill in the 18th century, the Senate in the 19th century and the president receiving it and signing it into law in the 20th. Though the Constitution does not expressly forbid this wild scenario, it implicitly does. The same is true for amendments, both their proposal and their ratification. The various acts necessary to make an amendment cannot stretch across decades or centuries.