Watergate: The aftermath

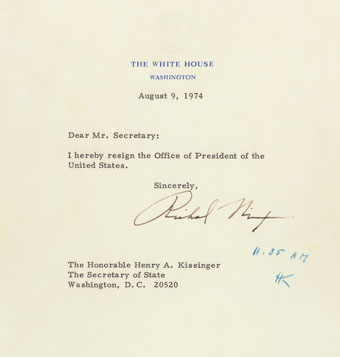

Nixon resigns, then Ford pardons him

Therefore, I shall resign the presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as president at that hour in this office.

With those words, Richard Nixon became the first—and so far only—president to announce his resignation, effective August 9, 1974. He was doing so, he said, because “the interests of the Nation must always come before any personal considerations.”

“From the discussions I have had with congressional and other leaders, I have concluded that because of the Watergate matter, I might not have the support of the Congress that I would consider necessary to back the very difficult decisions and carry out the duties of this office in the way the interests of the nation will require. I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as president, I must put the interests of America first.”

Nixon's downfall, however, came not so much from lack of congressional support—though that was the proximate cause—as it did from what is undoubtedly history's most transparent look into of the presidency of the United States. Nixon's secret White House tapes, uncovered in the course of the Senate Watergate hearings, revealed the truth about the Nixon presidency—and about Nixon himself. As much as Americans may have wanted to believe the president when he told them that he wasn't involved in the Watergate cover-up, the tapes proved otherwise. Americans could not reconcile Nixon’s public statements with the private recordings, and many could reach only one conclusion: Their president had lied to them.

"I let down my friends. I let down the country. I let down our system of government—the dreams of all those young people that ought to get into government but they think it's all too corrupt. . . . I let the American people down. And I have to carry that burden with me for the rest of my life."

The Miller Center’s Ken Hughes—presidential historian and expert on the Nixon administration—discusses the aftermath of Watergate with Tom van der Voort, former Miller Center media specialist.

The pardon

Before 2024, Americans had never seen a former president on trial. They would have if another President had not made an unprecedented decision fifty years earlier.

“Richard Nixon has become liable to possible indictment and trial for offenses against the United States,” President Gerald R. Ford said in an official proclamation on Sept. 8, 1974. “Whether or not he shall be so prosecuted depends on findings of the appropriate grand jury and on the discretion of the authorized prosecutor.” President Ford affirmed his predecessor had a constitutional right to a fair trial by an impartial jury, but expressed doubts that he could get one any time soon. “I have been advised, and I am compelled to conclude, that many months and perhaps more years will have to pass before Richard Nixon could obtain a fair trial by jury in any jurisdiction of the United States,” Ford said in a televised address. He predicted dire consequences resulting from the delay: “ugly passions would again be aroused,” “our people would again be polarized,” and the “tranquility” that had followed Nixon’s resignation “could be irreparably lost.” For those reasons, Ford said, he was granting Nixon “a full, free, and absolute pardon” for all crimes he committed as President.

The pardon immediately sparked the kind of polarization it was intended to avoid. “Most Republicans Approve, Democrats Condemn, Pardon,” the Washington Post reported from Capitol Hill the next day. A lopsided majority of Americans disapproved of Ford’s decision. The next Gallup poll found twice as many opposed to the pardon as in favor, 62 percent to 31 percent. Americans interviewed by the Los Angeles Times raised ethical concerns. Joseph Hickel of Santa Monica suggested that the pardon would lead subsequent presidents to conclude they could break the law: “I think there is a danger for future crimes. Everyone knows Nixon committed crimes, and [yet] he is not to be punished.” Others were concerned about equality under the law. “Giving that pardon makes it seem that the man in office is a king,” said Ann Robinson of Cerritos. John Dawdy, a Vietnam veteran and law student, asked, “What about the others in his administration who are being tried?” Former Attorney General John N. Mitchell, former White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, former Chief Domestic Adviser John D. Ehrlichman, and others had been indicted for conspiring with Nixon to obstruct justice (the legal term for the Watergate cover-up). Ford had not pardoned the men who carried out Nixon’s illegal orders, only the man who gave them. (Mitchell, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman were all found guilty and sentenced to prison. Although their crimes had been discussed on the front pages of newspapers for months, they all received fair trials.)

President Gerald Ford defended his pardon of Richard Nixon before the House Judiciary Committee on October 17, 1974.

Some Americans expressed support for Ford’s decision. Dr. Gilbert Ross called the pardon a smart move: “Mr. Ford can now get on with the business of the country.” His wife, Janice Ross, said Nixon was already being punished: “He will be punished for the rest of his life. They couldn't make him suffer more.” Nixon had not been impeached by the House of Representatives or convicted by the Senate, but it appeared likely that he would have been if had he not resigned voluntarily. His political support among congressional Republicans had evaporated quickly in the weeks before he stepped down. On July 24, he had lost a Supreme Court case 8 to 0. At issue was whether the President had to comply with a subpoena from the Watergate special prosecutor to turn over White House tapes that could contain evidence of crimes. Writing for the court, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, rejected the notion that the President had “an absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances.” One of the subpoenaed recordings, the June 23, 1972, “Smoking Gun” tape, captured the President plotting to obstruct the Watergate investigation by claiming, falsely, that it would expose classified activities of the Central Intelligence Agency. Following the publication of a transcript of that tape, congressional Republicans informed the President that they could not protect him from House impeachment or a Senate conviction.

Nixon’s fall from power, just two years after he won the biggest Republican landslide in history, was, for him, a painful, public humiliation. Some Americans viewed it as punishment. That view was particularly widespread among his fellow Republican politicians. California’s Republican governor, Ronald W. Reagan, said, “I think it is important to recognize that Mr. Nixon has suffered as much as any man should.” It was not the first time that law-and-order politicians took a permissive attitude toward lawbreaking by one of their own, nor would it be the last.

Following the pardon, Ford’s approval rating plummeted from 71 percent to 50 percent. The dramatic drop became the standard explanation for why he lost to Jimmy Carter in 1976, though many factors worked against him—7.8 percent unemployment, his unique status as the only chief executive who had never been elected president or vice president, and the strength of the primary challenge by Ronald Reagan that nearly deprived him of the Republican nomination. Carter’s problems as President began to make Ford look better in hindsight, to the point that in 1980 Reagan seriously considered nominating Ford as his vice presidential running mate. As Ford grew more popular, so did his most unpopular decision. Gallup polls showed Americans even split on the pardon (46 percent in favor, 46 percent opposed) in 1982 and supportive of it (54 percent in favor, 39 percent opposed) in 1986. Sen. Edward M. “Ted” Kennedy [D–Massachusetts], who opposed the pardon at first, presented Ford with the John F. Kennedy Foundation’s Profiles in Courage Award in 2001. “His courage and dedication to our country made it possible for us to begin the process of healing and put the tragedy of Watergate behind us,” Sen. Kennedy said.

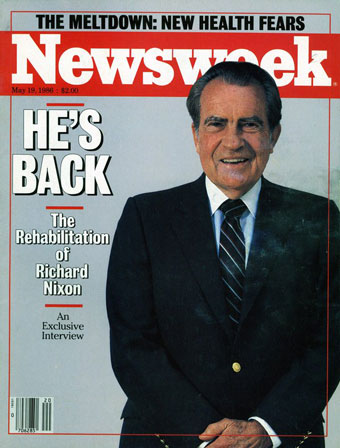

Nixon, the elder statesman

With legal jeopardy no longer an issue, the former president set out to rehabilitate himself and his reputation, to become a "new Nixon" one last time. His 1977 series of televised interviews with journalist David Frost and the 1978 publication of RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon gave him an opportunity to tell his side of the Watergate story—and injected badly needed cash into his bank account. By 1980 he was living in the New York City area and accepting the many opportunities to give his opinion on foreign affairs: For all the domestic turmoil his presidency had engendered, Nixon was still the man who had opened China, negotiated arms-control treaties with the Soviet Union, and brought to an end, no matter how painful, the Vietnam War.

Six more books followed. When Nixon finally passed away in 1994, his funeral was attended by every living president. "May the day of judging President Nixon on anything less than his entire life and career come to a close," said President Bill Clinton that day. But Watergate still resonates as the most memorable and significant aspect of Nixon's career.

Rethinking the pardon—50 years later

In recent years public opinion on Ford’s decision has shifted again. A 2018 poll by The Economist and YouGov found public opinion on the Nixon pardon evenly divided, with 38 percent in favor, 38 percent opposed, and the rest not sure. President Donald J. Trump had made the pardon power all too relevant again, declaring on social media, “I have the absolute right to PARDON myself.” None of his predecessors, including Richard Nixon, had claimed the power of self-pardon. At the time, special counsel Robert S. Mueller III was investigating any links between Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign and the Russian government. In 2019, Mueller issued a report containing evidence that Trump had obstructed justice. Mueller did not recommend charging Trump at the time, citing a 2000 opinion by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel stating that a sitting President may not be prosecuted, while “recognizing [that] immunity from prosecution for a sitting President would not preclude such prosecution once the president’s term is over or he is otherwise removed from office by resignation or impeachment.”

Following his defeat in the 2020 presidential election, Trump’s failed attempts to remain in office against the will of the majority resulted in criminal charges of election interference in state and federal court. He was also indicted on criminal charges of illegally retaining classified documents. The first case against him that went to trial was a criminal charge of falsifying business records in connection with a payoff to a porn star to avoid a potential scandal prior to the 2016 election. Trump had his lawyers argue before the Supreme Court that even as a former president he enjoyed absolute immunity from criminal prosecution. All of these cases remained pending in the spring of 2024 as the Republican National Convention prepared to renominate Trump for president, creating the prospect—unique in American history—that a criminal defendant could successfully evade prosecution by becoming president.

Trump’s novel claims to be above criminal prosecution have led some historians to conclude that Ford’s pardon of Nixon did less to heal the body politic than a jury trial would have done. Political historian Rick Perlstein regrets the lost opportunity for a legal reckoning, one that would have sent a clear signal that America would not tolerate lawbreaking at the highest level. “I think the cost to the country was colossal. I think it caused a cascade of élite wrongdoing that was specifically enabled by this single act of determining that the Presidency was ‘too big to fail,’” Perlstein said. Military historian Max Boot wrote, “The kid-gloves treatment Nixon received created an expectation of criminal impunity for both sitting and former presidents that leads Republicans to think that it’s an outrage for Trump to be probed by prosecutors, no matter how many laws he might have broken.” Garrett M. Graff, author of Watergate: A New History, concluded that the “precedent Ford set seems to have paralyzed a half-century of prosecutors.”

Tom DeFrank, a journalist who interviewed Ford many times over a span of 32 years, thought that Ford would still stand by his decision to pardon Nixon were he alive today. “But given his sense of personal probity and respect for the office, he would have been appalled by the way Trump behaved as President,” DeFrank said. “So, I suspect that he’d believe Trump should be pursued to the full extent of the law.”