Richard Nixon: Foreign Affairs

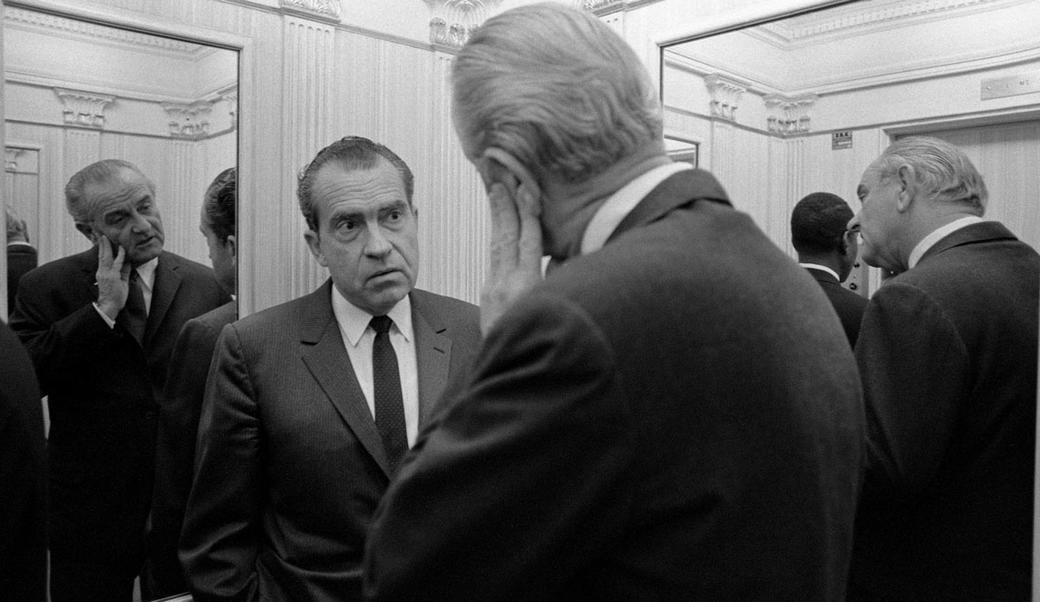

President Richard Nixon, like his arch-rival President John F. Kennedy, was far more interested in foreign policy than in domestic affairs. It was in this arena that Nixon intended to make his mark. Although his base of support was within the conservative wing of the Republican Party, and although he had made his own career as a militant opponent of Communism, Nixon saw opportunities to improve relations with the Soviet Union and establish relations with the People's Republic of China. Politically, he hoped to gain credit for easing Cold War tensions; geopolitically, he hoped to use the strengthened relations with Moscow and Beijing as leverage to pressure North Vietnam to end the war—or at least interrupt it —with a settlement. He would play China against the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union against China, and both against North Vietnam.

Nixon took office intending to secure control over foreign policy in the White House. He kept Secretary of State William Rogers and Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird out of the loop on key matters of foreign policy. The instrument of his control over what he called "the bureaucracy" was his assistant for national security affairs, Henry Kissinger. So closely did the two work together that they are sometimes referred to as "Nixinger." Together, they used the National Security Council staff to concentrate power in the White House—that is to say, within themselves.

Opening to China

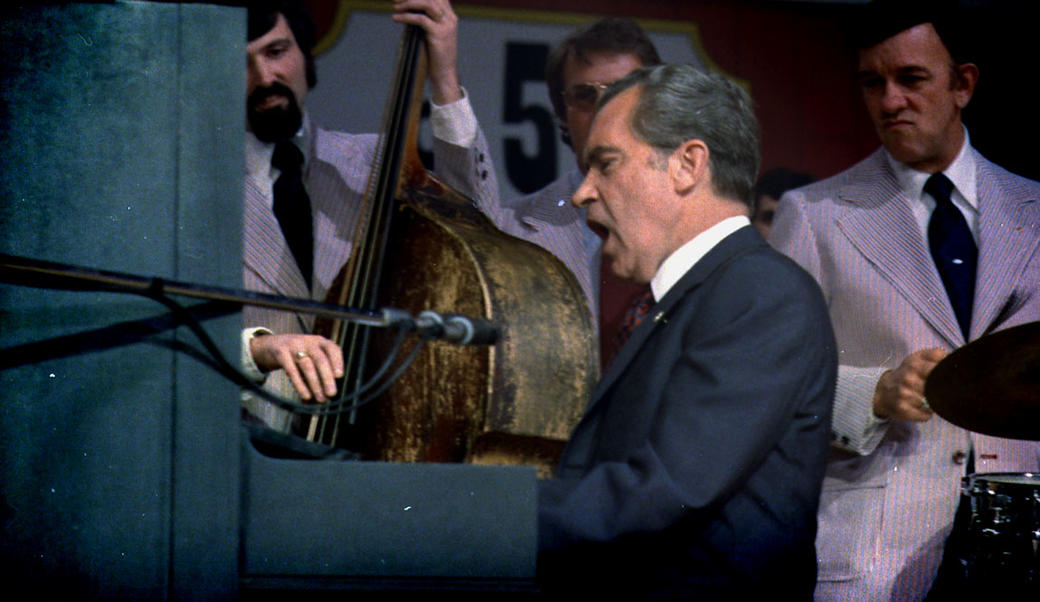

A year before his election, Nixon had written in Foreign Affairs of the Chinese, that "There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation." Relations between the two great communist powers, the Soviet Union and China, had been deteriorating since the 1950s and had erupted into open conflict with border clashes during Nixon's first year in office. The President sensed opportunity and began to send out tentative diplomatic feelers to China. Reversing Cold War precedent, he publicly referred to the Communist nation by its official name, the People's Republic of China.A breakthrough of sorts occurred in the spring of 1971, when Mao Zedong invited an American table tennis team to China for some exhibition matches. Before long, Nixon dispatched Kissinger to secret meetings with Chinese officials. As America's foremost anti-Communist politician of the Cold War, Nixon was in a unique position to launch a diplomatic opening to China, leading to the birth of a new political maxim: "Only Nixon could go to China." The announcement that the President would make an unprecedented trip to Beijing caused a sensation among the American people, who had seen little of the world's most populous nation since the Communists had taken power. Nixon's visit to China in February 1972 was widely televised and heavily viewed. It was only a first step, but a decisive one, in the budding rapprochement between the two states.

Detente With the Soviet Union

The announcement of the Beijing summit produced an immediate improvement in American relations with the U.S.S.R.—namely, an invitation for Nixon to meet with Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev in Russia. It was a sign that Nixon's effort at "triangulation" was working; fear of improved relations between China and America was leading the Soviets to better their own relations with America, just as Nixon hoped. In meeting with the Soviet leader, Nixon became the first President to visit Moscow.

Of more lasting importance were the treaties the two men signed to control the growth of nuclear arms. The agreements—a Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty and an Anti-Ballistic Missile treaty—did not end the arms race, but they paved the way for future pacts which sought to reduce and eliminate arms. Nixon also negotiated and signed agreements on science, space, and trade.

Withdrawal from Vietnam

While Nixon tried to use improved relations with the Soviets and Chinese to pressure North Vietnam to reach a settlement, he could only negotiate a flawed agreement that merely interrupted, rather than ended, the war.

In his first year in office, Nixon had tried to settle the war on favorable terms. Through secret negotiations between Kissinger and the North Vietnamese, the President warned that if major progress were not made by November 1, 1969, "we will be compelled—with great reluctance—to take measures of the greatest consequences." The NSC staff made plans for some of those options, including the resumed bombing of North Vietnam and the mining of Haiphong Harbor. Nixon then took a step designed both to interfere with Communist supplies and to signal a willingness to act irrationally to achieve his goals—he secretly ordered the bombing of Communist supply lines on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Cambodia. Also in keeping with his intention to convey a sense of presidential irrationality—Nixon as "madman"—he launched a worldwide nuclear alert.

None of it worked. The North Vietnamese did not yield; Nixon did not carry out his threats; the war continued. Nixon did not know how to bring the conflict to a successful resolution.

The President did not reveal any of this to the American people. Publicly, he said his strategy was a combination of negotiating and "Vietnamization," a program to train and arm the South Vietnamese to take over responsibility for their own defense, thus enabling American troops to withdraw. He began the withdrawals even before he issued his secret ultimatum to the Communists, periodically announcing partial troop withdrawals throughout his first term.

After a coup in Cambodia replaced neutralist leader Prince Sihanouk with a pro-American military government of dubious survivability, Nixon ordered a temporary invasion of Cambodia—the administration called it an incursion—by American troops. The domestic response included the largest round of antiwar protests in American history. It was during these protests in May 1970 that National Guardsmen fired at rock-throwing protestors at Kent State University in Ohio, killing four. Two weeks later, police fired on students at Jackson State University in Mississippi, leaving two more dead.

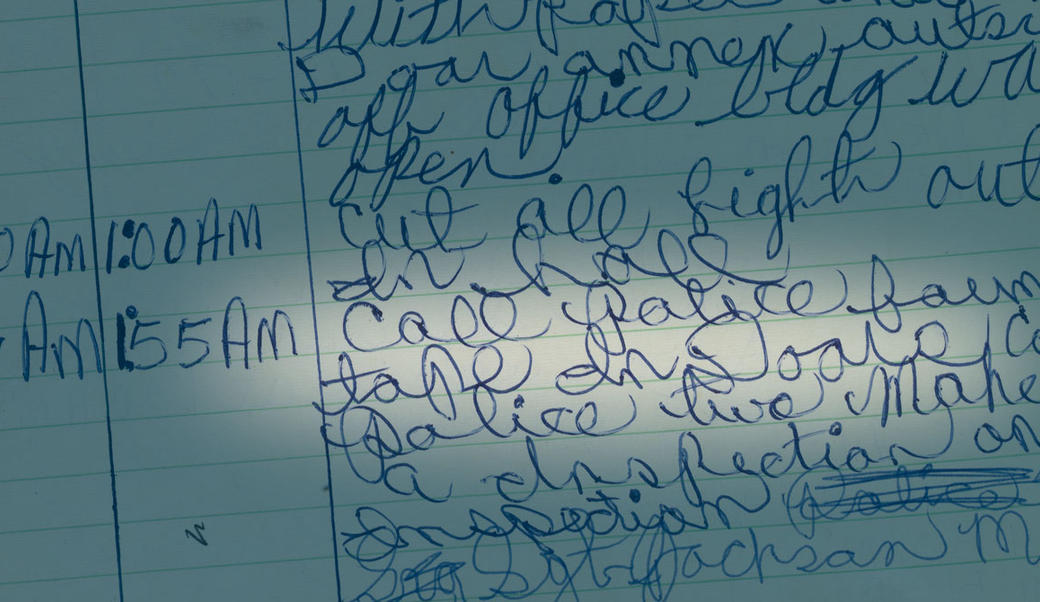

By the end of the year, Nixon was planning to finish the American military withdrawal from Vietnam within eighteen months. Kissinger talked him out of it. Nixon's chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, recorded this discussion in his diary on December 21, 1970. "Henry was in for a while and the President discussed a possible trip for next year. He's thinking about going to Vietnam in April [1971] or whenever we decide to make the basic end-of-the-war announcement. His idea would be to tour around the country, build up [South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van] Thieu and so forth, and then make the announcement right afterwards. Henry argues against a commitment that early to withdraw all combat troops because he feels that if we pull them out by the end of '71, trouble can start mounting in '72 that we won't be able to deal with, and which we'll have to answer for at the elections. He prefers instead a commitment to have them all out by the end of '72 so that we won't have to deliver finally until after the [US presidential] elections [in November 1972] and therefore can keep our flanks protected. This would certainly seem to make more sense, and the President seemed to agree in general, but he wants Henry to work up plans on it."

In 1971, South Vietnamese ground forces, with American air support, took part in Lamson 719, an offensive against Communist supply lines on the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos and Cambodia. Since American troops would not take part in ground combat operations in either country, Lamson was considered a test (at least a partial one) of the success of Vietnamization. By all accounts, it went badly, but it disrupted Communist supply lines long enough to aid the war effort.

Nixon and Kissinger anticipated that the biggest threat to their plans would be a dry-season Communist offensive in 1972. Their worst fears were realized when the North Vietnamese regular army poured into the South in March 1972. Nixon responded by implementing some of the plans he had made in 1969. He mined Haiphong Harbor and used B-52s to bomb the North. The combined power of the American and South Vietnamese military ultimately stopped the offensive, though not before the Communists had more territory under their control.

The North Vietnamese were eager to reach a settlement before the American presidential election and subsequent removal of U.S. forces from the country. Hanoi made a breakthrough proposal in October 1972 and reached agreement with Kissinger rapidly. The South Vietnamese government balked, however, chiefly because the agreement preserved North Vietnamese control of all the territory Hanoi currently held. To turn up the political pressure on Nixon, the North Vietnamese began broadcasting provisions of the agreement. Kissinger held a press conference announcing that "Peace is at hand" without giving away too many details.

After the election, Nixon told South Vietnamese president Thieu that if he did not agree to the settlement, Congress would cut off aid to his government—and that conservatives who had supported South Vietnam would lead the way. He promised that the United States would retaliate militarily if the North violated the agreement. To back up this threat, he launched the "Christmas Bombings" of 1972. When negotiations resumed in January, the few outstanding issues were quickly resolved. Thieu backed down. The Paris Peace Accords were signed on January 23, 1973, bringing an end to the participation of U.S. ground forces in the Vietnam War.

Beyond the "Big Three"

Nixon's policies vis-a-vis China, the Soviet Union and Vietnam are his most famous and controversial, but he left his mark on a host of other diplomatic matters.

The 1973 October War alerted America to the power of oil-producing Arab nations to impose a great price - literally, in the form of higher fuel costs - to force a compromise on the disposition of lands Israel seized in the Six Day War of 1967. When Egypt and Syria attacked Israel on Judaism's holiest day, Yom Kippur, they were backed up by Gulf oil states that announced a price increase of 70 percent; and when Nixon asked Congress for emergency aid to Israel, Arab officials imposed a total embargo on oil shipments to the United States. American dependence on foreign oil meant the crisis would not be resolved on military terms alone.

With Nixon distracted by Watergate, Kissinger took charge of policy. A large-scale American airlift of supplies prevented Israeli defeat; a ceasefire negotiated with the Soviet Union forestalled Israeli victory. When Israel continued fighting after the ceasefire deadline (with Kissinger's tacit acquiescence), the Soviets threatened unilateral action. Kissinger responded by putting American forces worldwide on DefCon (for Defense Condition) Three. The Soviets' tone changed. Instead of unilateral action, they now spoke of sending observers, not soldiers. The war ended soon thereafter with no apparent victor. Over the next several months, Kissinger helped redraw the lines of the Middle East and inspired the term "shuttle diplomacy" as he flew from capital to capital seeking agreement. The result was, as one observer put it, "a reasonably stable situation on the Sinai and Syrian fronts."In Chile, Nixon's opposition to the democratically elected president, socialist Salvador Allende, helped pave the way for a military coup whose legacy of death and despotism burden that nation still. Following Allende's election, Nixon authorized the CIA to prevent him from taking office by any means. General Renee Schneider, the Chilean army chief of staff, supported his country's constitution and opposed any coup plot. With U.S. encouragement, right-wing Argentine military officials tried to kidnap Schneider, wounding him fatally on October 22, 1970.

Nixon cut American aid to Chile, which had been running $70 million a year, to less than $1 million. The CIA continued to be involved in anti-Allende political activities before the socialist president died in a military coup on September 11, 1973. A junta led by General Augusto Pinochet replaced Chile's democracy with despotism. Allende supporters were rounded up and detained in Santiago's National Stadium. More than a thousand, including two Americans, were summarily executed. The evidence that has emerged to date indicates that Nixon had no direct involvement in the coup; the President, however, had done much to suggest that he would welcome one. Fearing a tyranny of the Left, he quickly embraced a tyranny of the Right.