Richard Nixon: Impact and Legacy

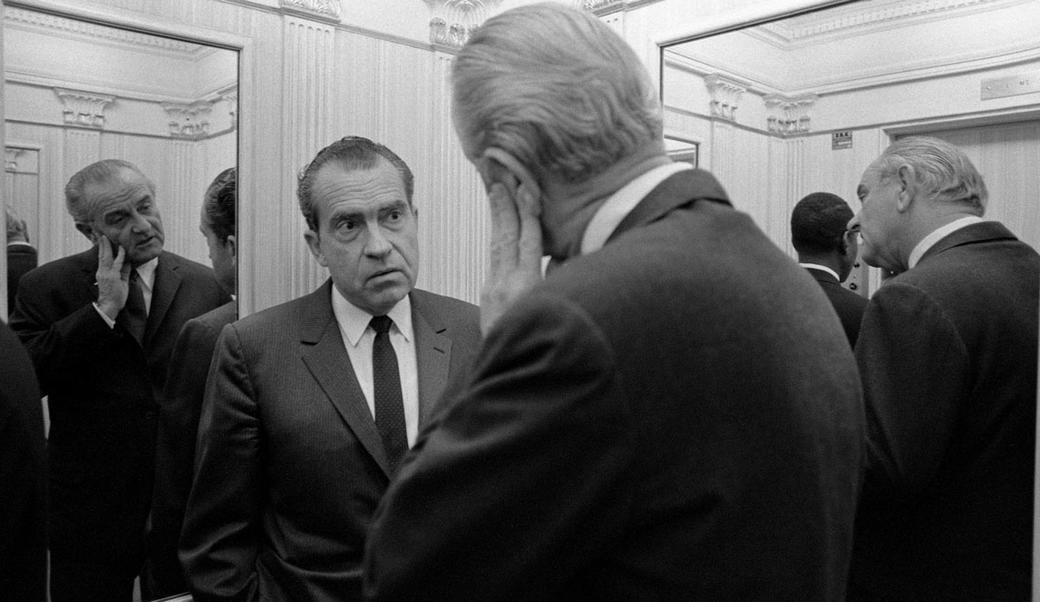

Richard Nixon's six years in the White House remain widely viewed as pivotal in American military, diplomatic, and political history. In the two decades before Nixon took office, a liberal Democratic coalition dominated presidential politics, and American foreign policy was marked by large-scale military interventions; in the two decades after, a conservative Republican coalition dominated presidential politics, and direct military intervention was by and large replaced with aid (sometimes covert, sometimes not) to allied forces. Nixon intended his presidency to be epochal and, despite being cut short by Watergate, it was.

Nixon and his presidency are often termed "complex" (sometimes "contradictory"). Scholars who classify him as liberal, moderate, or conservative find ample evidence for each label and conclusive evidence for none of them. This should be expected of a transitional political figure. In foreign and domestic policy, Nixon's inclinations were conservative, but he assumed the presidency at the end of the 1960s, liberalism's postwar peak. He could not achieve his overarching goal of creating a governing coalition of the right without first dismantling Franklin Roosevelt's coalition of the left.

Nixon and his presidency are often termed "complex" (sometimes "contradictory"). Scholars who classify him as liberal, moderate, or conservative find ample evidence for each label and conclusive evidence for none of them. This should be expected of a transitional political figure. In foreign and domestic policy, Nixon's inclinations were conservative, but he assumed the presidency at the end of the 1960s, liberalism's postwar peak. He could not achieve his overarching goal of creating a governing coalition of the right without first dismantling Franklin Roosevelt's coalition of the left.

As President, Nixon was only as conservative as he could be and only as liberal as he had to be. He took credit for the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency while privately noting that if he had not taken this liberal step, the Democratic Congress would have forced more liberal environmental legislation on him. This was a President who could philosophically oppose wage and price controls and privately express the conviction that they would not work, while still implementing them for election-year effect. Still his tactical flexibility should not obscure his steadiness of political purpose. He meant to move the country to the right, and he did.

Nixon's most celebrated achievements as President—nuclear arms control agreements with the Soviet Union and the diplomatic opening to China—set the stage for the arms reduction pacts and careful diplomacy that brought about the end of the Cold War. Likewise, the Nixon Doctrine of furnishing aid to allies while expecting them to provide the soldiers to fight in their own defense paved the way for the Reagan Doctrine of supporting proxy armies and the Weinberger Doctrine of sending U.S. armed forces into combat only as a last resort when vital national interests are at stake and objectives clearly defined.

But even these groundbreaking achievements must be considered within the context of Nixon's political goals. He privately viewed the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks and the China initiative as ways to blunt criticism from the political left. And while his slow withdrawal from Vietnam appeared to be a practical application of the Nixon Doctrine, his secretly recorded White House tapes reveal that he expected South Vietnam to collapse after he brought American troops home and prolonged the war to postpone that collapse until after his reelection in 1972.

Ultimately, the White House tapes must shape any assessment of Nixon's impact and legacy. They ended his presidency by furnishing proof of his involvement in the Watergate cover-up, fueled a generation's skepticism about political leaders, and today provide ample evidence of the political calculation behind the most important decisions of his presidency. They make his presidency an object lesson in the difference between image and reality, a lesson that each generation must learn anew.