Watergate: The Cover-Up

Threats, lies, and audio tape (Chapter 2)

“It's going to be forgotten.”

That was President Richard Nixon's first assessment of the Watergate break-in on June 20, 1972, three days after five men were apprehended for unlawfully entering Democratic National Committee headquarters.

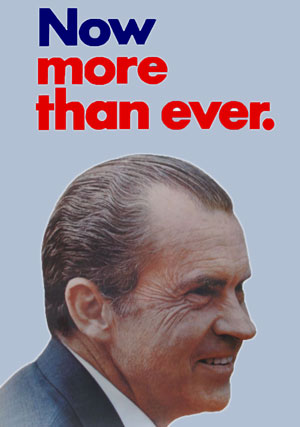

He was right—in the short-term. Less than five months later, 23.5 percent more Americans voted for Nixon than for Democrat George McGovern. America's involvement in Vietnam was ending—albeit in failure—relations with China and the Soviet Union were improving, and the nation seemed ready to embrace the 1970s. For Nixon, who saw every campaign as a tough, dirty street fight, this was the last election. And it was a landslide.

“The Smoking Gun” and “Deep Throat”

Despite declaring "It's going to be forgotten" to aide Charles Colson, Nixon must have felt some trepidation. Because three days later, he discussed the FBI's investigation with his chief of staff, H. R. “Bob” Haldeman. The Bureau had already connected the burglars to E. Howard Hunt, who reported directly to Colson.

Nixon agreed to let Haldeman and another aide, John Erlichman, instruct the CIA to thwart the FBI investigation. The plan was captured on a voice-activated taping system in a recording that came to be known as “the smoking gun.”

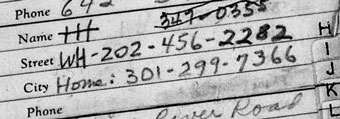

During the conversation, Nixon and Haldeman also discussed associate director of the FBI Mark Felt, who they thought would be helpful in protecting the president. Years later, the public would learn that Felt was keeping Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein informed about the investigation using the code name "Deep Throat."

On August 1, Woodward and Bernstein revealed that a $25,000 check made out to the Nixon campaign had been deposited in the bank account of one of the burglars. Before the election, they also reported on widespread intelligence-gathering and sabotage operations directed against political opponents. None of these revelations hurt the president—at least not immediately.

Nixon's second term

In early January, 1973, as Nixon was preparing to begin his second term, seven men faced justice in the courtroom of Judge John Sirica: the five caught in the Watergate Office Building, along with Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, who had been overseeing the burglary from a nearby hotel room. By the end of January, all had either pleaded guilty or, in the case of Liddy and burglar James McCord, been convicted.

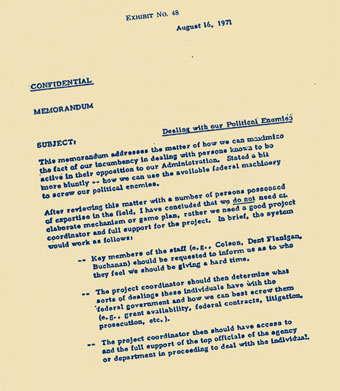

But White House counsel John Dean, who had been trying to keep Watergate from spinning out of control, was uneasy. On March 21, 1973, he went to see Nixon. (Listen to an extended excerpt of the discussion below). Realizing that the president didn't fully understand the implications of the burglary and the cover-up, Dean offered a full, clear, and candid explanation, calling the matter "a cancer—within—close to the presidency." Dean acknowledged his own legal jeopardy and that of Haldeman, Erlichman, Colson, and former Attorney General John Mitchell. And he suggested "continued blackmail" by Hunt and the other Watergate burglars could leave Nixon vulnerable.

Dean also pointed to one other disturbing trend: participants were starting to decide that it was more important to protect themselves than to protect the president. Soon enough Dean himself would turn state's evidence. His decision to testify about the Watergate cover-up prompted the White House to attempt to blame the cover-up on him.

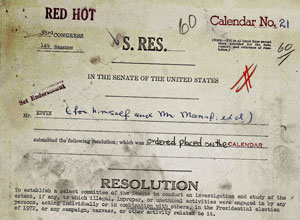

Less than two miles away, on the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, the US Senate was also beginning an investigation. During Hearings to confirm Patrick Gray as the replacement for J. Edgar Hoover as FBI director, Gray revealed he had cooperated with Dean to keep the White House informed on the scandal. And following the passage of Senate Resolution 60, a select committee under Senator Sam Ervin (D-NC) was assigned to study “the extent, if any, to which illegal, improper, or unethical activities were engaged in by any persons, acting either individually or in combination with others, in the Presidential election of 1972.”

The dam begins to crumble

As the Watergate Committee prepared to begin its work, Nixon tried once more to contain the situation. In a nationally televised address on April 30, he presented himself as completely innocent, blaming his aides for keeping him in the dark and telling the nation that Dean, Haldeman, Erlichman, and Attorney General Richard Kleindienst, a longtime friend, had resigned. And he vowed to take charge of the investigation in a quest to discover the truth. In short, Nixon looked directly at the American people and lied. For all those protecting Nixon, the message could not have been clearer: you may have to be sacrificed.

But the president's men knew too much, and all of them were not willing to sacrifice themselves to protect Nixon. And on May 17, 1973, they began to appear, one by one, before Ervin's committee. A day later, new Attorney General Elliott Richardson fulfilled a promise made to the Senate during his confirmation hearings: He appointed Archibald Cox as a special prosecutor to investigate Watergate.

Highlights from the Watergate Committee hearings as compiled by PBS NewsHour

The tapes: Nixon's last line of defense

With Dean and several other Watergate participants deciding to tell all, Nixon still enjoyed the presumption of innocence from many Americans. But during the hearings, Alexander Butterfield, a Nixon aide, revealed the installation of a voice-activated taping system in the Oval Office. Now Nixon's word could be weighed against not just those of burglars or admittedly corrupt staff members trying to protect themselves, but also against a real-time record of events. Nixon's only hope was to fight to keep the tapes out of the Watergate investigation.

Both the Senate Watergate Committee and Special Prosecutor Cox requested the tapes. Nixon refused, taking his case to the American people: “Many have urged that in order to help prove the truth of what I have said, I should turn over to the special prosecutor and the Senate committee recordings of conversations that I held in my office or on my telephone. However, a much more important principle is involved in this question than what the tapes might prove about Watergate,” he said. “This principle of confidentiality of presidential conversations is at stake in the question of these tapes. I must and I shall oppose any efforts to destroy this principle, which is so vital to the conduct of this great office.”

Then, in late October, he took more aggressive action, firing Cox. When Attorney General Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckleshaus decided to resign rather than execute Nixon's order, the event became known as the “Saturday Night Massacre.”

But the Senate Committee, the House Judiciary Committee, and the new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, were not satisfied. In early March 1974, a Federal Grand Jury indicted Haldeman, Erlichman, Colson, Mitchell, and three other Nixon aides.

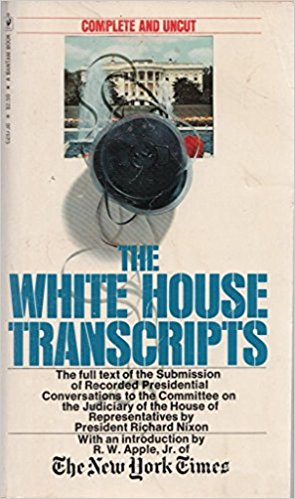

The following month, Jaworski issued a subpoena for 64 recordings. Instead of turning over the recordings, the White House released more than 1,250 pages of edited transcripts of Nixon's conversations, including the March 21, 1973, “cancer on the presidency” discussion with Dean. Far from putting the matter to rest, the transcripts showed some of the president's worst qualities—and they raised more questions about Watergate than they answered. Why was the president, for example, discussing raising a million dollars in connection with the Watergate burglars?

On July 24, 1974, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in U.S. v. Nixon that executive privilege does not cover the recordings pertinent to the Watergate investigation. “The decisive result of the case of the president's tapes,” said the New York Times, “adds to the feeling that the last act of Richard Nixon's drama is at hand.”

Three days later, the House Judiciary Committee passed the first of three articles of impeachment—for obstruction of justice. It was the beginning of the end of the Nixon presidency.