Transcript

Knott

Thank you, Dr. Sullivan, for being with us today. This is the George H. W. Bush Oral History interview. We're delighted that you're here. We've gone over the ground rules, so we can dispense with that. One of the things we like to do right off the bat to help our transcriber is to go around the table and have everybody identify themselves. My name is Stephen Knott.

Chidester

I'm Jeff Chidester.

Derthick

I'm Martha Derthick.

Riley

I'm Russell Riley.

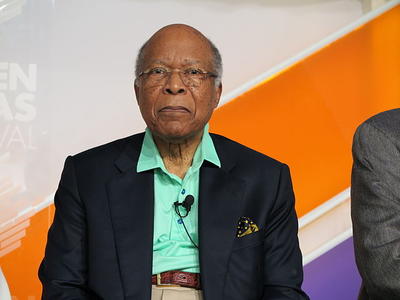

Sullivan

And I'm Lou Sullivan.

Knott

I guess probably the best place to start would be to ask you if you could tell us about how you first met both George and Barbara Bush, and the circumstances surrounding that.

Sullivan

Surely, right. I met them, actually, in my role as then president and dean of the Morehouse School of Medicine. Our medical school is one of 46 new medical schools that opened in the last half of the 20th century in what I consider to be a remarkable period of expansion of medical education that occurred. Basically, in the mid-'50s there were a number of reports that were issued suggesting that we as a nation would be facing a doctor shortage if we didn't expand medical education. That led to a number of efforts, including health manpower legislation passed by the Congress I think in '63, which was the vehicle that provided for such programs as the National Health Service Corps, a number of scholarship programs, funds for construction, for new faculty, for residency support, et cetera.

So as a result of that, we have now today 126 medical schools, whereas we had 80 medical schools in 1950, before this started. Morehouse School of Medicine was one such school. Interestingly, [it] is the only predominantly African American medical school that was started during this time. There are three schools. Two that existed prior to that time were Howard University in Washington, which had opened in 1868, and Meharry in Nashville in 1876. The effort briefly that led to the development of the Morehouse School of Medicine was a report issued in 1969 by a special committee appointed by the Georgia Comprehensive Health Planning System. This special committee was to look at physician manpower needs in Georgia during this period of expansion. At that time President [Jimmy] Carter was Governor of Georgia and he supported the effort. So when he went to Washington as President, he continued to support our efforts and we were able to influence some legislation that was helpful to us.

Then 1980 came. Carter lost, and [Ronald] Reagan came in. We decided that it would be helpful to develop some relationships with the Reagan administration, so we invited President Reagan to speak at the dedication of the first building that we had under construction for the medical school, which was a $6.25 million building, of which $5 million was a federal grant that we had gotten. So our goal was to try and develop a relationship with the Reagan administration similar to what we had with the Carter administration.

After holding us up for a long time with the invitation that went in late January of '81, we finally heard in October of '81 that President Reagan could not come. Meanwhile--I'll just say parenthetically--it was mixed feelings we had when we got that news that the President could not come. You may recall that in March of '81 he announced his budget where he slashed education funding quite significantly, so that worried us. Then in August of '81, he then also voiced support for the policies of Bob Jones University in South Carolina, which prohibited interracial dating and other things like that. By this time, the image of President Reagan that was emerging, certainly in the black community, was not a very positive one.

So in one sense we were kind of relieved because, as you know, Atlanta is also the home of such people of Joe Lowery, head of the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], and Andy Young, John Lewis, and a lot of other leaders in the civil rights movement, of course. I was thinking at the time that if Reagan accepted, I might have to get on the plane with him when he left, for survival. But rather than just accepting that--because we had a different view of the Bushes--we then sent a letter back that said, with courteous language, but very clearly saying, "How could you hold us up all these months, only then to tell us the President could not come? Perhaps you could help us get the Vice President." And that worked.

In July of '82, Vice President Bush came and was a speaker at the dedication of this first building we had constructed. Our construction had started in 1978 in facilities on the college campus, so the land that we had gotten and the building we'd constructed was actually across the street from Morehouse College. Parenthetically, let me mention that the medical school, while being started by Morehouse College, started as a two-year school but became a four-year school in 1981. That approval from the accrediting committee to become a four-year school triggered the separation of the medical school from Morehouse College. There are several reasons for that. The primary one, actually, is the fact that Morehouse College is a part of a consortium, the Atlanta University Center. The consortium dates from 1929. The 1929 agreement, which still is operative today, was that the colleges shall operate baccalaureate programs, and graduate and professional programs will be operated by Atlanta University.

So Morehouse College starting a medical school was really an anomaly. There's some history behind that but I won't go into that unless you want. But at any rate, we had become independent from the college at the time that Vice President Bush came down to speak at the dedication of the building. That's when I first met him. This is 9 o'clock in the morning, because he had to be in New Orleans to speak at a luncheon that day. We had been warned by his staff he could stay only about 15 minutes for the reception afterward. It turned out he stayed more than an hour. All these Democrats--Andy Young, John Lewis, then Ed McIntyre, who was Mayor of Augusta at the time, and others--were right there getting their pictures taken with the Vice President.

So the bottom line was that we had had some concerns as to how he would be received, and it was obvious to us that his staff had concerns as to how he would be received. It was our own speculation--it was never confirmed by his staff--it was our speculation that we had been given this 15-minute story so that they would have a graceful way to leave in case this didn't go well. But it went well. As he was getting ready to leave, one of his aides gave me a little box in which were vice presidential cuff links, saying, "The Vice President wants you to have these," which was fine. So anyway, it went off very well.

About two weeks later I received a call from Vice President Bush. In fact, my secretary buzzed on the intercom, "The Vice President is on the telephone." I said, "What Vice President?" She said, "How quickly you forget." I thought it was a vice president of one of the other schools or what have you, so sure enough, he was on there. What he said was, he was going to Africa in November of that year and wondered if I would go with him as a part of this delegation. So I said, "Gee, Mr. Vice President, I would be pleased to go. But not being a government official, what would be my role as part of your delegation?"

He said, "Well, Lou, to be honest with you, we don't have an Andy Young in our administration. I don't think that I, as Vice President of the United States, should go to Africa without some prominent African American as part of my delegation. You'd do me a big favor and the country a good service if you'd be willing to go, because I think you could help our delegation." So I said fine. I appreciated his honesty here. So on that trip in November of '82, which was a two-week trip, there were two other African Americans on that trip. Benjamin Payton, who was president of Tuskegee University--and parenthetically Bush had spoken in Tuskegee in the fall of '81, about nine months before he spoke at our place. The other African American was Arthur Fletcher. Fletcher had been Assistant Secretary of Labor in the [Richard] Nixon years.

So at any rate, there were three of us, although none of us were at that time government officials. So two weeks, going to eight countries in Africa. While Vice President Bush was meeting with heads of state, I would usually tag along with Barbara Bush, because she was constantly speaking to adult literacy groups in such places as Zaire, now the Congo. She spoke at the dedication of Belvedere College in Zimbabwe, built with USAID [U.S. Agency for International Development] funds, an agricultural school along the model of Tuskegee, et cetera. So that I found interesting, fascinating.

On the way back to the United States, I was talking with Barbara. We'd gotten to know each other quite well by this time. It was amazing.

Riley

How long had it been?

Sullivan

Two weeks on this trip. You get to know everybody traveling around on a trip like that, because visiting eight countries in two weeks is quite a marathon. So I told Barbara that I was very much interested and intrigued with her adult literacy initiative and basically that was education, which was what I was involved in. I said, "You need to be on my board." So she said, "Oh no, Lou, for me to do something like that I'd have to get clearance from the White House counsel. Let me talk with them about that. It will probably take about six weeks for me to get an answer." I said, "Fine." She called about five days later. She said, "I can do it." So she came on our board in January of '83 and served on the board of Morehouse School of Medicine until January of '89, after Bush was elected President.

When she came on our board--first of all, she was a serious trustee. She missed only one meeting during that six years she was on our board. Plus, we had our first national fundraising campaign and she was our draw. We held luncheons around the country, San Francisco, Minneapolis, New York, Miami, et cetera. So she was a real trooper. She worked very hard. Meanwhile, my wife and I were always being invited to things at the Vice President's home. So we'd gotten to know both of the Bushes very well, and really formed a great friendship and affection for them.

I also learned, which I had not known before, that the United Negro College Fund, founded in the late '40s, George Bush's mother was one of the founding directors of the UNCF. There has been a Bush on the board of the UNCF ever since that time. I guess [William] Bucky Bush out in St. Louis is now the current Bush family member there. So I became very enamored of the Bushes because of their obvious support for higher education generally, and certainly for the African American community as well. So when Bush ran for President, I offered, and my wife and I did host a reception at our home for him in early 1988, primarily to introduce him to the black community. Because within the black community, being part of the Reagan administration with a number of things, there was a little suspicion about who he was, what he stood for so far as the interests of the black community.

So we did this with the idea that this would be helpful, because as I've mentioned Atlanta, for the African American community, is a very important city. Having an endorsement from Atlanta would be helpful. As you may remember, the "peanut brigades" when Carter ran for President, came out of Atlanta, a lot of people going all over the country. So having African Americans in Georgia or Atlanta, going to Boston or other places saying, "This guy Carter, white farmer from the South, but he's fine, he's great, et cetera." I envisioned a similar--not anything that extensive--but kind of a similar principle here in having this reception.

Riley

Dr. Sullivan, can I interrupt?

Sullivan

Sure.

Riley

Did you have any other background in political activity before this engagement with Vice President Bush?

Sullivan

No, other than campus politics. No, I'd not served in any government capacity whatsoever.

Riley

Did you consider yourself a Republican at the time?

Sullivan

No, I considered myself an independent. In fact, the first political argument I had with my father was in 1960, during the Nixon-Kennedy election cycle, when I told my father I was going to vote for John F. Kennedy. We had our first and only argument then, because my father was a Republican, but I consider myself independent.

My father was Republican because he was of the age when a number of blacks his age identified with the Republican Party because of several factors. One, this was the party of [Abraham] Lincoln, with emancipation. Secondly, I was born in Atlanta but had grown up in a small town in southwest Georgia. My father was pretty much of an activist. He formed the first chapter of the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] in Blakely, Georgia, where we were. Really did a number of things, trying to repeal the poll tax and the various tests for voter education, where someone would be given something from [Immanuel] Kant or what have you and asked to interpret this, and all kinds of things like that.

Frankly, this is back in the late '30s and '40s in rural Georgia, as in other places, the Klan was still active. My father was an undertaker. Among other things, among the bodies he had, were a couple of people who had been burned, who were lynched. So my father was a real activist and the people who were on his neck were Democrats. There was no Republican Party in the South. So in 1960 when I told my father I was going to vote for a Democrat, we had a big argument. It was fine, because of course he himself later became quite enamored of Kennedy. So I had not considered myself part of any Democrat or Republican Party, but prided myself on being independent, so I would choose my votes depending upon the individual.

Riley

You mentioned President Carter earlier. Did you have any kind of ongoing relationship with President Carter?

Sullivan

No, no. First of all, I finished Morehouse College in 1954, then went to medical school at Boston University. So I was in Boston. Then later on I was on the faculty at Boston University. So during the Carter years, I was in Boston when the "peanut brigades" came through. Then when I went to Morehouse in '75, Carter was--I guess that was during the election cycle, because I did then go to an event in Washington to speak on Carter's behalf. This was because he had been supportive of the medical school. That as I remember was the only real relationship I had with Carter.

The people who were interested in starting the medical school--which was kind of an interesting phenomenon itself in terms of the evolution of the South--the leadership for this effort were black physicians, but hand-in-glove with them supporting this effort were white physicians in Georgia, too. We received the endorsement not only of the state chapter of the National Medical Association of Black Physicians, but also the state chapter of the AMA [American Medical Association], the white physicians. Rhodes Haverty, the white physician who was then president of the state AMA chapter, was dean of the School of Allied Health at Georgia State. So in a sense this was kind of an interesting thing that was happening, what was going on. That effort really started right after this report in 1969.

Several things happened between '69 and '75, when I came on board. A feasibility study was done. I mentioned the fact that Morehouse College started a medical school rather than Atlanta University. That's because what happened was Dr. Louis Brown, a black physician who was president of the Georgia State Medical Association, which is the state NMA [National Medical Association] chapter, was a member of this committee that recommended expansion of medical education in Georgia, because Georgia ranked 38 among the 50 states in overall physician manpower. This report further noted that in addition to being below the national average, when you looked at the fact that Georgia's population included 27 percent African Americans, but less than 2 percent of the physicians were African American, this report recommended that any expansion of medical education in the state should also address the shortage of black physicians.

So Louis Brown then brought that report to the presidents of the consortium, the Atlanta University Center, arguing that this should be the basis for a medical school to be started in the Atlanta University Center. Atlanta University was the logical institution to do this, but they turned it down. They thought this was risky, expensive, medical schools are troublesome. Universities that have them, they take half the budget or more, and all of that. So they wanted no part of it. But Hugh Gloster, the president of Morehouse College, was sitting at the trustees' meeting of Atlanta University in April of '71, when the trustees of Atlanta University accepted the recommendation from Dr. Thomas Jarrett, who was president of Atlanta University at the time, that they should not proceed. They had done a feasibility study that said this was not feasible.

But Hugh Gloster then, after that vote, said that now that the trustees of Atlanta University had voted, would there be any objection to Morehouse College looking at this idea? And there was none. The importance of that question is this agreement in the Atlanta University Center, which started the consortium in 1929, because technically it would be a violation of that agreement for a college to undertake graduate or professional education. Morehouse College did their own feasibility study in, I guess, in February of '72 they received federal dollars to do this, and a year later they concluded differently. It was feasible and was needed, et cetera. Then they got funds to do a planning study.

In 1974 I first got involved in this effort, because of what happened at Morehouse College with a small team of three people who were really managing this. They put together a committee of Morehouse College alumni who had positions in academic medicine around the country, so I was one of those people. Interestingly enough, other members of that advisory committee included Dave Satcher, who was then out at the Charles Drew Medical School in Los Angeles. I had finished in '54; Satcher I think finished in '61. A third member was Henry Foster, who was a classmate of mine, finished in '54. Foster, you may remember, was a Surgeon General's candidate who was rejected because he's an obstetrician and had performed abortions. So that was kind of an aside.

So at any rate, my involvement as a member of this committee was to advise the college on this idea of a medical school. I approached it with some skepticism because this is a college, not a university, and with all of the demands that a medical school makes. But to make a long story short, having approached this with skepticism, I became enamored of the idea that this really was something feasible after all. Then when they started the search for a dean for this, I put together a list of 11 names of people that I suggested that they consider. That was in, I guess, in September of '74. About two weeks later I got a call from Joe Gayles, who was the chairman of the small group at Morehouse College, thanking me for my list but also expressing some disappointment that it was not complete. I said, "What do you mean it's not complete?" My first reaction was All this time I spent.

Then halfway through I said, "Oh, wait a minute, no, look, I'm not a candidate. I'm perfectly happy as Professor of Medicine at Boston University and Head of Hematology at Boston City Hospital." Had NIH [National Institutes of Health] research grants plus an NIH training grant for trainees and all of that. Plus, as I was telling Steve last night, my wife is from Massachusetts, three children, all born in Massachusetts. By this time we had bought a summer place down on Martha's Vineyard. So I really had never envisioned myself going anyplace else. Joe Gayles said, "Well, we anticipated this would be your answer, but would you be willing to come down to New York in about two weeks to meet with the committee that's looking at this side of the school, as a consultant, not a candidate?" So I said, "Sure."

At the end of that meeting, which was two weeks later, it was a luncheon meeting, but it lasted until about 4:30. This committee, I should mention, included not only Joe Gayles, who was Professor of Chemistry at the college who was leading this project, looking at the medical school, but included Hugh Gloster, the president of the college; Arthur Richardson, who was dean of the Emory University School of Medicine; Pierre Galletti, who was Vice President for Medicine and Biology at Brown; and two or three other people whom I don't really remember.

But at any rate, at the end of this afternoon, Hugh Gloster said, "Well, Dr. Sullivan, I know you came here as a consultant, as one of our college alumni. You have stated that you're not really a candidate, but I hope that as you drive back to Boston this afternoon, you think about that. Because I can't speak for my fellow members on the committee, but as far as I'm concerned, you're the man we want. I'd like to see you leading this effort." So, sure enough, driving back up the Connecticut turnpike, with the fall color--by the way, I was a leaf peeper, because I love to go up into New Hampshire and Vermont with my camera in the fall and all that sort of thing--and I was thinking, Gosh, you don't have fall color like this in Atlanta.

Anyway, I asked my wife, "Do you think you could ever consider living in Atlanta?" She had visited with a friend of hers in New York, by the way, and had come back twice to pick me up and I told her, "Wait, come back in another hour, I haven't finished." She said, "I knew this was going to happen."

Riley

Forgive me, I got you off track earlier, at the point that you were beginning to host some events for the Bushes and the presidential campaign in '88. I had merely wanted to get a kind of picture about any existing partisan inclinations before then, because it's a fascinating story about your own involvement with the Republican administration. So I'll bring you back to that.

Sullivan

Why don't I come back to that. So my wife and I hosted this. As it turned out, Vice President Bush himself couldn't make it, but Barbara was there. Of course, as you know, Barbara is a charmer. She's probably a better campaigner than Bush himself. So it came off very well.

Meanwhile, one of my trustees on the medical school board desperately wanted to be Secretary of HHS [Health and Human Services]. He had been a finalist in 1985, remember, when Margaret Heckler went off to Ireland as ambassador. Otis Bowen came in then as Secretary. Monroe Trout, who was my trustee, was at that time senior vice president of Sterling Drug Company in New York, which later was bought by Kodak, et cetera, but Monroe had been one of three finalists in '85 for the Secretary's position. What happened with Monroe, he was interviewed by Don Regan, White House Chief of Staff, and they didn't hit it off, so that was the end of that.

Riley

That's the only time I've heard somebody crossing swords with Don Regan. [laughter]

Sullivan

So that was that. I mentioned that when Barbara came on our board, my wife and I were constantly going to things at the Vice President's home. But also, Barbara hosted--I mentioned our campaign. We had the final luncheon with the success of the campaign, which was a campaign at that time of $15 million, and I think we raised $17 million. We had the victory luncheon at the Vice President's home with members of the campaign committee including Monroe Trout, my trustee who desperately wanted to be Secretary.

Vice President Bush came by that luncheon while we were there. That was in 1986 that we concluded that. So with the campaign in '88, coming back to that, Monroe mentioned this to me and said, "Lou, looks as if Bush may win. You know, I was a finalist before and I still would like to have a shot at this. Would you support it?" I said, "Sure, I think you'd be a great Secretary." So I mentioned this to Vice President Bush one of the times I saw him and said, "You know, the campaign is going well. Monroe was a finalist before. He really would be a great Secretary." He said, "Oh yes, fine, sure."

I shared this with Monroe, so he knew that. In the fall of '88, I received a call from Dr. Frank Royal. Now Frank Royal is a black physician here in Richmond, who's Republican and prominent and he was close to Senator [John] Warner and others. I knew Frank from medical association meetings. Frank called me and said, "Lou, I just want you to know that I'm putting your name in to be Secretary of Health and Human Services." I said, "No, no, Frank. Look, I'm not political, I've never done this. Plus, I already have a candidate I'm supporting, one of my trustees." So we went on for about 20 minutes.

Frank said, "Look Lou, I didn't call to ask your permission. I just called to tell you this because I think you'd be the person." I said, "Okay Frank, if you want to do that, fine. But you're wasting your time." Well, interestingly enough, about a week later I received a second call from Dr. Leroy Keith, who at that time was president of Morehouse College and had a similar conversation, only this one was much shorter. I said, "Roy, look. I had a similar conversation with Frank Royal. Since you want to do this, then you go right ahead."

Sure enough, the day after the election I called then President-elect Bush down in Houston. Parenthetically he was wearing a tie on election night, when he came out to acknowledge, that I had bought and sent to him as a gift. In New York, on Fifth Avenue, you've probably passed a shop, [inaudible], I don't know if they're still there now. An interesting men's and women's clothing shop. There happened to be a nice blue tie with tiny red elephants on it, so I bought this and sent it to him and said, "Wear this on Election Day. It will bring you good luck." Sure enough, that night in Houston he was wearing the tie. So the next day, when I called to congratulate him, I said, "See, I told you. Had you not worn that tie, you'd be packing up." So we kidded.

Then I said, "Remember, we talked about Monroe before, who would be a great Secretary," because I had not taken these conversations with Royal and with Leroy Keith seriously. He then said, "That's right, Lou. I remember we talked about this, but I'm not getting kind of the reaction I think I need if I'm going to go forward with this name. So would you be willing to come up in a couple of weeks? I'd like to talk with you about this." So I said, "Sure," and I hung up. I said, "What did he mean by that? Was it talk about how do we get Monroe the position, or it sounds to me as if he wants to talk with me about becoming Secretary."

So I spoke to the chairman of my board. I told him, "I'm not sure, I may be blowing smoke or imagining things, but it may be that Bush wants to talk with me about becoming Secretary." He said, "How do you feel about it?" I said, "I'm not sure." Frankly, this really was a resetting of my compass, because I was focused completely on developing this new medical school.

But I also spoke with the Speaker of the House of the Georgia legislature. The reason for that was we had gotten state support for the school. Tom Murphy, who actually was just defeated recently, had been Speaker the whole time I'd been in Atlanta and we'd gotten his support for the medical school. One of my worries was if I pop up in Washington, even talking about going into a Republican administration, would this damage our relationship? So I went to see Tom Murphy. Interesting guy. We have a good relationship, but Tom Murphy wears cowboy boots, has a Stetson hat, is about 6? 4?, and he looks at you in a scowl. You never know whether he's pleased or not pleased. He has a little wedge of tobacco that he stuffs in his mouth, and he has a spittoon, had a spittoon right there.

By the way, I'd also learned through my colleagues--I'd go out and visit him in Bremen, his home, during the off-season. He appreciated that, so we developed a relationship. So I went to see him, said, "Mr. Speaker, I want to talk to you, because President-elect Bush has asked me to come to Washington. I think he may be asking me if I'd become a member of his administration, and I thought I'd want to talk with you and see what you thought about that." He looked at me, and he's chewing this, and he says, "Well, it's all right with me because there's not a dime bit of difference in my view between Bush and [Michael] Dukakis." [laughter] So that was my blessing, because he didn't like Dukakis.

So I went, and sure enough Bush asked if I would come into his administration. That's really the way it happened.

Knott

Then you introduced Barbara Bush at the Republican Convention that year?

Sullivan

Yes.

Knott

Can you tell us a little bit about that, anything that stands out from that event?

Sullivan

Yes, the way that happened was as I mentioned, Barbara really was a great trustee. As you know, she's a great person. One of the times I was up visiting with then Vice President Bush, he said, "You and Ginger [Sullivan] are hosting this reception, and Barbara's going to make a speech down there. Would you be willing to introduce her?" He also said at the time, "Lou, I don't know what your political affiliation is and I don't care. I don't know whether you're Republican, Democrat, Independent, or what have you. But you're our friend and if you'd be willing to do that, because Barbara thinks so much of you, it would be great of you to do that." Again, I touched my bases and they said fine.

So Ginger and I went down and we spent, I guess, several days down there and I gave the introduction. That really was purely because of our friendship with the Bushes and my appreciation to her for her tremendous role she had played as a trustee, because she really helped us quite a bit. Again, at that time, had no thoughts of myself becoming politically involved. My focus was on the school. I thought I'd play a role in helping to get my trustee at HHS because my vision was: Bush in the White House, Monroe as Secretary and me at Morehouse; that's it, I have it made. But that's not the way it happened.

Knott

Did you get the impression, for instance at this reception that you held at your home that Barbara Bush attended, was she able to convert people? Was it a hostile audience to some extent and by the end of the evening had she won them over? Did you have any sense of that at all?

Sullivan

Actually, no, it was really a pretty friendly audience. Interestingly, in the same way we had expected that when Bush spoke at our dedication, we'd have a hostile audience--let me back up and give you one other interesting thing when Bush spoke at our dedication. This was outside on the plaza in front of the building that was dedicated. Across the street, behind the police lines were about 15 demonstrators. So I'm uptight, thinking, Oh my goodness, what a reception for the Vice President, because I want this thing to go well.

He comes out and of course he's wearing his bulletproof vest underneath. I became very much aware of all the security and all these other things. He looked across the street and I'm feeling embarrassed and he says, "Hmm, only 15. Hell, if Reagan were here, there'd be 50." [laughter] So he was disappointed that there were not more. At any rate, that's how that happened. He was well received. Then when Barbara--this was back in, I guess in the fall of '88, or August. I have to go back and check to see exactly when this reception was, but no, she was well received. Also, it was well known by that time she was one of our trustees. Of course, she had been our main draw with this campaign, had been successful. So no, she was warmly received.

Derthick

Was there anyone other than the Speaker of the House in Georgia whom you felt you had to explain yourself to?

Sullivan

No. Governors come and go, but Tom Murphy lives forever.

Derthick

Until recently.

Sullivan

Yes, right. That was kind of in jest, but the reality is that Tom Murphy was a prominent--and if I had his blessing, then I knew that had there been objections elsewhere, I could say, "Look, I talked to Tom Murphy and got his blessing."

Riley

Do you remember the particulars of your conversation with the President-elect? You had indicated that you were going up to him. Could you tell us a little bit about how that conversation unfolded?

Sullivan

Sure, sure. He asked about my prior political involvement. I'll share this with you, my meeting with Bush was 10 o'clock, I've forgotten what the day of the week was. It was 10 o'clock in the morning. I flew up the night before; this was in December, no, late November of '88. I stayed in what was then the Carlton Hotel; I've forgotten the name. It's the hotel right on 16th Street, right down from the Hay-Adams and across the street from the Capitol Hilton Hotel.

Knott

It's the St. Regis now.

Sullivan

Right. That's the hotel but it was the Carlton or something like that. I came up the night before because I wanted to be sure if the weather was bad. So I had a nice leisurely breakfast and then about 9:30 I took a walk over through Lafayette Park to the White House. Just as I was crossing 16th Street and I was heading for the gate, I guess the northwest gate there, going by the circular drive of the White House, I noticed a bunch of people standing on the other side, but I didn't pay much attention. I was about halfway across the street when I heard someone say, "There he is." All of a sudden, these cameras wheeled around and these were reporters, including reporters from Atlanta. Because they, of course, get the President-elect's schedule, which I never even thought about, they knew with whom he was meeting at the time. Of course there was interest about who was he going to be appointing to various things.

As I got across the street this reporter said, "I understand you're meeting with President-elect Bush today, is that right?" I said, "Yes, this is a meeting that he requested." "Is he going to offer you the Secretary's position for HHS?" Because that had been speculation. I said, "I have no idea what the President-elect wants to talk to me about, but I certainly am pleased to respond to his question, et cetera." I'm certainly feeling, This is a mistake. These cameras are right on me. So I try to go in the gate. There were some cars parked in the circular drive and I'd forgotten, some visiting head of state was there, so that gate was sealed. They said, "I'm sorry, you can't come in here for security reasons. You have to go down, there's another gate going in through the Old Executive Office Building, you can go in that gate."

So here I am out there with these cameras and so forth, trying to walk as fast as I can without breaking into a trot to get away from them. I went in through this other gate, into the Old Executive Office Building. Of course, they couldn't come in the gate, so finally, once I got in the gate--because remember, there's a wide plaza there before you get into the building. So I went in there, and they typed in everything. Then they said, "Oh, yes, you have this meeting. We know you just came from this area, but President whoever-he-was is gone now, so we'd like to have you go back to the original gate." So I had to do this again in reverse. I finally got in. I'm trying just to not say anything, but at the same time not appear panicked or what have you.

I got in and then inside I met with Craig Fuller, who was one of his assistants, and with John Sununu. I'd met Craig before but I met Sununu for the first time. Also, one of those polling people whose name will come to me, from Michigan.

Riley

Bob Teeter.

Sullivan

Bob Teeter, yes. I met with then President-elect Bush and indeed he said, "Lou, I would like very much if you would be my Secretary of Health and Human Services," and so forth. He said, "You have an outstanding medical career. Now one of the things you'll find and will have to be prepared for are questions on abortion. You can talk with my staff, but in my administration what I want is teamwork. We work closely together." So having been prepared for this possibility, I said, "I'd be pleased--" In my meeting with him, he was wearing, by the way, cowboy boots with GB on them, some gift that somebody had given him before the election with the American flag implanted on them and so forth, which I thought was a little incongruous for a Connecticut Yankee who was trying to be a Texan.

At any rate, we had a good meeting, but only about 15 or maybe 20 minutes at the most. Afterward I met with Teeter and Sununu and Fuller, they kind of put me through a drill: "These are some of the things here and also stay away from the press because the President will be announcing this at some time and Congress is very jealous of their prerogatives for confirming people so you don't want to be out talking to the press," et cetera. So I said, "Fine." They also said, "Try and stay out of sight." I then said, "I've already learned my lesson," and told them what happened. They said, "What? You walked?" They were thinking, Oh my goodness, what kind of hayseed is this guy? He doesn't even know--So they said, "We'll arrange transportation out of here." And that was my last time I ever walked to the White House. I tried to stay undercover.

Meanwhile, they prepared briefing books for me and I had a little office there in the Old Executive Office Building for preparation. I stayed in Washington, went back to Atlanta I guess a day or so later, but then came back, really to go through all the briefings, about the department and everything else. At any rate, that's how things got started.

Riley

You had decided in advance that you would accept.

Sullivan

Yes, because when I met with my chairman, for example, basically he said that, first, for you personally this would be a great honor. Secondly, for the school, this would give us prominence and this would be very positive. You can't turn the President down if that's what--so I had really touched all the bases here. Everyone I talked to including Murphy, Speaker Murphy, was saying in essence, "Okay, fine."

My biggest personal perspective was, believe it or not, I said, "Do I really want to do this?" Because I was very excited about what I was doing, and I felt that I knew something about that. This was another world out there. But in talking with everyone, I also talked with my wife, decided that this would be not only an honor but a real opportunity and be interesting, be something different. Undergirding all of that, frankly, was our great affection for the Bushes. I felt it would be a great honor as well as fun working with them. So those are the thoughts at the time.

Chidester

During this meeting with Bush, before he offered you the job, did he ask you about your political persuasion? Or did he just offer it to you based on what he knew of you?

Sullivan

What he knew of me. Basically, when he had asked me to introduce Barbara at the Republican Convention, he had then said, "I don't know and I don't care what your political affiliation is. You're our friend and that's the basis we would like to have you do that." So no, we didn't have any discussion there about political affiliation.

Knott

He did mention the abortion issue as something that might cause controversy, is that right?

Sullivan

Yes, because it had caused controversy for him, too. And as subsequently happened, it did. I made the mistake of saying the Supreme Court has ruled on this, it's the law of the land, so legally women have a right. That was a very intense lesson I then learned. These very guys, Sununu and Teeter and Craig Fuller had said, "Don't talk to the press." But what had happened, when I was back in Atlanta, this reporter wanted to talk with me and said he wanted to do a profile of me. This would be embargoed until after my confirmation and so forth, so that's fine. Well, I talk with him and the next day it's in the press. So that was an introduction to the press at that time.

Derthick

I want to ask you, did this associating with Republicans cost you socially among African Americans, either within Atlanta or Martha's Vineyard or anywhere else? Were you viewed with suspicion or disdain?

Sullivan

In the long run, no, but early on, yes. There were questions, because this was viewed as really, the Republicans are not very interested or supportive of the issues that are important to blacks. You know, education, health care, civil rights, affirmative action, et cetera. So there were some questions like that, but not a real confrontation. There were questions as well, "Now, what's Sullivan going to do, is he going to be a turncoat and mouth the Republican line?" So there was that kind of questioning and skepticism. "Is he being an opportunist to become a Cabinet member?"

Over time I think all of that's disappeared because fundamentally I've made clear what my position is on education and on health, and frankly it's been fairly interesting. Now I'm being given great accolades for founding the medical school and the medical school itself is doing well, and we have a number of graduates there and my public positions on a number of things--and, at the same time, as you probably know, I'm currently chairman of the current President [George W.] Bush's advisory council on black colleges and universities. Basically I'm working to try and enhance federal support for these institutions, which I frankly see as consistent with the Bush family's interests.

Another interesting thing, too, that you're probably familiar with, having talked to other people in Bush's Cabinet, they don't blow their own horn. That is, most people don't know that there's been a Bush as a member of the UNCF board from the beginning. I talked with President Bush once about this saying, "People don't really--" And he said, "Well, I know, Lou, but I just don't believe in that kind of thing." This was kind of a Bush tradition, his mother and all that sort of thing. So I know that is still out there, and certainly with W. now. But again, what I'd point out is that W. has appointed more blacks to Cabinet positions and senior positions than any other President, Republican or Democrat. So there's that tension and that ambiguity and that questioning and so forth.

My position and the position I've taken is I know who I am and I know what I represent and what I try to do. I also know that in the political world, to be successful, sometimes you have to compromise. It may not be the most comfortable thing, but sometimes you have to compromise on this thing over here so you can get this thing over here. If you're an ideological purist where you're not willing to do that, then fine. You stay in your ideological purity, but I think you might be less effective in getting something done if you're not willing to compromise.

This has been and is still an ongoing issue, I think, certainly in the black community there. But that's also been an interesting thing. I think socially we've not suffered anything. Occasionally somebody will still say, "How can you be a Republican?" The way you say it when you're spitting out something very bad. But I point out to people, "Look, my father said the people who were stepping on his neck and keeping him from voting were not Republicans, because there weren't any in the South, they were Democrats." So really, you could say both parties have some blemishes here and either you work with what we have and try to improve it, or you stay above it. That's one way of addressing things, but that may not be the most effective way if you're interested in social change.

Riley

I want to ask you one related question about your own devotion to the Bushes. You've explained to us that there are people who were very open, in their personal lives, to being supportive of African Americans and being very inclusive, and really putting their time and their money where their mouths were. Some would argue that there's a difference between that and the kinds of policies that people might produce within an administration. I'm wondering, in your own case, how much the policy-related questions concerned you as you were trying to make a decision about casting your lot with these folks? Was it the case that because of your own personal relationship with them you had such a high degree of comfort that you could overlook where you felt there were shortcomings in their policy commitments? Or was it the case that their policy commitments really were very much consistent with your own, at least within the realm of Health and Human Services?

Sullivan

I think it's more the former rather than the latter. Let me give you an example of another area where this operated. As you know, during my time as Secretary, I was very outspoken against tobacco use. Of course the tobacco companies and the Republican Party really were hand-in-glove. I first spoke out, I guess it was in January of '90. Yes, I'd been in office just about a year. I did this, at the time, knowing that Bush had not done that. Also, that I was going beyond where the administration was. But I had decided by that time, If I get fired about this, so be it. This is one of those areas I did feel strongly about.

I knew that this was not in keeping with the position of the administration, but I decided I was going to push the limits on this and see what happens. Of course, what happened was nothing. Bush didn't come out and support me, but he also didn't come out and say, "What my Secretary said was totally wrong and not in keeping--" He was silent. Three or four months later we were at some program there in the Old Executive Office Building and he was commenting on me and says, "Of course, Lou has pointed out about the health dangers of tobacco. I know sometimes he may feel that there's a big empty echo behind him, but he's out there and he's doing a good job."

He was saying he wasn't going to get out there. Frankly, so far as I was concerned, that was fine. My feeling was that you do have to decide, where do I draw the line? Where do I say, "Okay, this is something that I have to do and if it costs me, then so be it"? That was one of those, but it didn't cost me. In fact, I later learned that someone from Philip Morris had contacted John Sununu to say, in essence, "Would you have the President call off his Secretary?" And John Sununu said to them, "I'll go to the President about this if you really want me, but you might want to think about that, because you may not get the answer that you want." So they backed off. I only learned this later; Sununu never said that to me directly.

When I learned about it, it was in an article in Time magazine that I saw it, and I just asked him and he affirmed it. So it was a situation where they knew that for their reasons, multiple, including the fact that--gosh, I've forgotten his name now, but a senior Republican who was from Richmond at the time--

Derthick

There was a member of the House, Tom Bliley.

Sullivan

Yes, Bliley, Tom Bliley, yes. I know he was not happy with me. Of course, Philip Morris has that huge facility down there. He was cordial, but he made it very clear he didn't really agree with or appreciate those comments. Mitch McConnell over in Kentucky also spoke with the White House, saying, "At least could you get him to not talk about our international markets," et cetera. So really, there was some compromising done there, but Bush made it clear, through his inaction, and it may have been more than that--because I never frankly pushed that. I never asked--but that wasn't going to be the tipping point that it otherwise could have been.

Knott

You had mentioned earlier the interview with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the issue of abortion coming up. Could you just talk a little bit more about the controversy that swirled around you on that issue?

Sullivan

Sure. Basically, I thought I was making a very careful statement when I said, "The Supreme Court has ruled on this and this is the law of the land, so that means that women have the right to that. As Secretary, I'd be pledged to uphold the law." I thought I was crafting a very careful argument where I was hiding behind the law. Obviously, as a federal official, I would have to uphold the law.

Well, of course this came out, "Sullivan pro-choice." That caused quite a flurry there and a number of meetings. I had a fellow who now is vice chairman of my board, and who had been an assistant to Liddy [Elizabeth] Dole when she was Secretary of Transportation during the Reagan years, who came and talked and said, "This is quite a thing. Why did you open your mouth?" And of course, I'm feeling pretty stupid, the same way I felt with these damned reporters chasing me down the sidewalk before, because I'd been warned, "Don't talk to the press." But I had thought, frankly, This was a reporter from my hometown. He wants to do a profile, I want to be supportive of him and he promised to embargo this, and all that kind of thing. Of course, that didn't happen. His name is [Kevin] Sack, he's now a reporter for the New York Times, so frankly, I was part of his ticket to another position. But when this happened, I had a number of people there at HHS go through all of the history, which quite frankly, part of my problem was abortion had not been an issue I'd been involved in.

As you know, my training was in hematology, blood diseases and so forth. So really, this was new to me. Frankly, at that time I was not aware of the intense emotions on both sides of the debate here, where there are these things that are used as signals as to your position here. But obviously, the fact that I did not come out at that time and say, "I'm opposed to abortion," by default then, I'm pro-choice. So frankly I was surprised and I was concerned.

Most of all I felt I'd let Bush down. I had inflicted an unnecessary wound, both on me and on him. I was very much aware that the right wing didn't really trust him. Therefore, here's the Secretary who's closest to this issue now having gotten caught up in this. Nevertheless, of course, at any time he could have very well said, "Well, Dr. Sullivan is taking a position that I do not agree with and regretfully we are withdrawing the nomination," or something like that, but he didn't do that. He stuck with me.

Riley

Dr. Sullivan, was the statement that you crafted--you mentioned you'd been given some, marching orders is probably too strong a word, but that you'd met with three of the President's advisors and you had talked about abortion at that time.

Sullivan

Right.

Riley

Were you repeating in your statement what you had heard from these three advisors, or were you revising and extending what you had heard from them?

Sullivan

I guess, no, I can't say that. The meeting with them was not that detailed, was not that intense. They said, "The President is not for abortion except for the life of the mother." I'm not sure, but I think they probably assumed that I was more familiar with the issues here than I really was, I don't know. But I frankly thought, also, in my own naivete, because my statement was one where I thought, as any government official, that my obligation would be to operate within the bounds of the law. So I thought that by saying, "This is the law of the land as determined by the Supreme Court, and I will take an oath to uphold the law"--But as was obvious with what happened after that, that was really not the thing to say. I was trying to make my response on legalistic grounds here, not on the ideology, that sort of thing. So that's what led to that.

Riley

Their primary admonition was just, "Don't talk to the press, period." You had formulated a statement that you felt was consistent with what the President had said.

Sullivan

Plus, what I thought I was doing, what I had been promised was talking to this guy for an article that was going to appear later. Giving him time for a profile and all that kind of thing. I really felt pretty stupid after that, because people said, "Don't you ever take the press's word for this." So all these things I had blandly assumed would be operative were not. I really was quite chastened by that because as we mentioned before, I had not been in political life and this was something where my education was coming in various incidents that were happening.

After that that I sat down with a number of people to understand all the issues. It turns out actually, my roommate from Morehouse College, who is an obstetrician, was out in Los Angeles. He and I were good friends; he's pro-choice. He said, "Lou, I thought you were smarter than this." He sat me down, of course we're friends, and said, "Now this is the argument over here, this is the argument over here, and there's no compromise. You're trying to walk down the middle. There's no such place as the middle ground here." That was a kind of baptism by fire there. I felt that Bush could have easily been justified in jettisoning my nomination, particularly where he, as I mentioned before, had also not been received with comfort and enthusiasm by some of the people on the right.

Derthick

If you had it to do over again, would you have just declined to give the interview to the reporter?

Sullivan

Oh sure, absolutely. I frankly felt like a chump. Here I am, how naive to believe somebody's word really stands for something, a reporter?

Riley

A pledge for an embargo is usually pretty solid, maybe we're being naive.

Sullivan

Well, I had accepted that as such. Of course, I'm sure there are reporters who really honor that, but some of my friends and advisors said, "Well, look, you never trust a reporter; I don't care what they tell you," because there are enough times something like this happens, where really, rather than being interested in honoring their word, they're interested in what kind of sensationalism they might get out of it.

Knott

Did you ever speak to him about it?

Sullivan

No, never spoke with him again. He tried to contact me to offer some apology and all of that, but I've never spoken with him again. That's one of my traits. If you give me your word on something and you go back on it, I don't have any use for you. I can deal with you if you're way over here on the right. I can argue with you and still have respect or way over there on the left or what have you. But if you give me your word about something, that's it. If you then go back on that, I'll never trust you again. I would never know when you would really do what you say you'd be doing.

Knott

Did you hear from Sununu or any of those people while this was swirling around those few days where it was headline news? Did the White House contact you at any point in the middle of this? Or were you left--?

Sullivan

Not directly. They did not, Sununu didn't. I don't believe Sununu called. The person whom I spoke with who is part of the pro-life community is Kay James, who ended up being my Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs. She really educated me about all of this here. And Debbie Steelman actually I had tried to recruit to be head of Social Security but she turned us down. They really put me through the paces then. At that time I'm the President's presumed nominee and they were working to do everything to salvage this. Part of this was to make sure that I really know what the issues are and I know what the line is and I know how to conduct myself and all that sort of thing.

Now, they never said this specifically and I didn't ask them, but I was pretty sure that they were doing this at the behest of the White House. Here again, I learned in the political world, sometimes it's better not to ask, just make assumptions.

Knott

Did you ever come close to thinking of withdrawing, that this has done too much damage to the President-elect?

Riley

Or that it was just not worth it, to have to deal with this kind of environment?

Sullivan

I wouldn't say I came close. I thought about it, but again, I decided that this would be his call and I would have accepted that had that happened. But I also, within me, said, "I'm going to fight this damn thing. I'm not a quitter and I'm not going to run away because of this." I said, "I have to learn what the issues are and really be a little smarter than I have been on this." So, I'd say there was never any serious effort, but I was prepared for that to happen, if it happened. And I was going to accept it with grace.

Among other concerns I had was, here was my friend for whom I have caused this problem. Because first of all, as you said, I was a political unknown so people would say, "Who's this guy? Why is--?" Plus there were a lot of other people, frankly, who wanted to be Secretary. Mike, Monroe Trout, Chick [C. Everett] Koop, Surgeon General, was one of the candidates, and other people who had been in the Vineyard, because Monroe Trout was head of the Republican Party up in Darien, Connecticut, and all of that. So here were other people you could say, on the basis of their involvement and on their contribution, they deserve to be out there in front of me. But I felt it was A) because of my personal relationship with the Bushes, and B) I wasn't naive either. I felt that he wanted to have an African American in his Cabinet and for those various reasons. So that's how that happened.

Knott

When you go out to Washington for the formal announcement, how did that go? Did the President say anything to you? Was there any joking about what had happened, or was it just put aside?

Sullivan

No, no. He said, "How you doing? You're not letting them get you down, are you?" and that sort of thing. But no specifics about, "What the hell did you say," or anything like that, nothing like that. My announcement, you may remember there were three other people there. I knew very well that having these three others was kind of cover for me, because the others were not controversial. There was Ed Derwinski to be VA [Veterans Affairs] Secretary, Manuel Lujan, and I think Bill Riley. I've forgotten who the fourth person was.

These were people there had not been any kind of controversy around. I mean, I was the poster boy at that time. So I felt he did this to diffuse it, because again, the questions afterward, really, all these other guys sitting up there, nobody had any questions for them.

Knott

You were announced with Riley, Derwinski, [Sam] Skinner, and Lujan.

Sullivan

Right.

Chidester

A lot of people have mentioned Bush's loyalty, especially to his friends. I guess this is a good example of that. Did that change the way that you felt about Bush personally, or how you conducted your job as Secretary?

Sullivan

It only enhanced it. That is, I had felt before--the fact that, when I offered to host this reception--see, I knew, the question you raised about the reaction of the black community--I knew, in offering to do that, or having him come, there would be people in the black community who would raise questions. But my feeling for the Bushes was really so strong for them as individuals that I was prepared to do that. And I felt that Barbara, as one of our trustees, had gone beyond the call of duty, traveling all over the country to speak at fundraisers and so forth. So for me there was no question I was going to do that, because I wanted to do it. I wanted him to win the election for President. I did this knowing that there could be some cost, but I was prepared to pay that.

Knott

Could you tell us about how you prepared for your confirmation hearings and the kind of support you were given by the White House?

Sullivan

Oh sure. Quite intense preparation. There is a common term I'm sure you're familiar with, "murder boards." I had two three-ring binders that talked about all of the issues. First of all, the various programs in the department, because there are 250 programs in the department. Of course, on so many of these programs there are a lot of strong feelings. Social Security being another one, disability issues, AIDS, a lot of hot button issues, welfare. So, my preparation started right after, well actually even started before this announcement. But it was really after I met with Bush in November, for all practical purposes, I was no longer at Morehouse. I really was preparing, learning the issues and so forth.

Tom Korologos really was the manager of the murder boards. As you know, the nickname for Thomas, he's the 101st Senator. I forgot what Tom's position is now, but he has his own lobbying firm, as you know. But he really managed that. I had a bunch of people, I had public relations people and we would have mockups in the room with people questioning me and throwing out questions. Also interrupting my answers and all of the things that could happen there that could rattle me. So it was both a question of A) do I really know the issue? Did I have enough of a knowledge base? And B) how did I handle myself, being interrupted, or being asked a question that's somewhat incendiary and that sort of thing? We were focusing on both content as well as style. So I had quite intense preparations.

Knott

And they were helpful?

Sullivan

Oh yes, very much so. There's no question. Bush was taking a big chance on me, which I'm sure he knew. Some of these nuances, not having anything to do with abortion, but just dealing with the press in a high-profile environment like that. Also, I thought I knew how to work with the press. I'd had the press there in Atlanta at Morehouse, new school and all of that. We'd had good press. I never had any disaster like this happen. But I learned that the Washington press is very different from the press in Atlanta.

Riley

Did you make the rounds on the Senate side of Capitol Hill? Did you go visit individual Senators at all?

Sullivan

Yes, oh yes. That reminds me, one thing I should mention is that once this abortion thing came up, and then I made a subsequent statement--a clarification saying I am opposed to abortion except for rape, incest, and life of the mother--Arlen Specter was a little concerned, "Where does this guy really stand?" I have to remember now how this came about. I think I met with Orrin Hatch. I'd known Hatch before, because of course in my role as head of the medical school I would come to Washington to lobby for things for us, and so I knew Hatch from that.

I hope I'm not remembering something that didn't happen, but it may have been Hatch who suggested that I ought to talk with Alan Simpson, or it may even have been the White House. To make a long story short, Alan Simpson called me, said, "Lou, we need to talk." He said, "You've got yourself wrapped around the axle on probably the worst thing," et cetera, and "We've got to work through this." So Alan Simpson took me over to see Arlen Specter in his private office, just the three of us. We talked about my position on abortion and what was it. I then told Specter, "Well, it really is what I said. I'm opposed except for rape and incest." He said, "Well, that didn't sound like what you said at first. Now is that true?" I kept repeating it. I'm not going to veer off of this catechism, I don't care what he says.

After this he said, "Okay, we're going to support you." I passed out because as you know, Specter is pro-choice. Basically, what was happening there, Alan Simpson, who's highly regarded in the Senate, was really putting his blessing on me so he was bridging this gap. So that's one of the things that happened in terms of my relations with the Senate.

Riley

You said in that particular instance there were only three of you in the room. Typically you would have been traveling in the company of someone from the congressional relations office?

Sullivan

Oh yes, absolutely.

Riley

Do you recall who that was at the time, who you were working with?

Sullivan

Gosh--

Riley

Korologos would have been an outside.

Sullivan

No, it wouldn't have been Korologos, no, no, no. I frankly don't remember, but it was someone from the department. It may come to me, but I frankly don't remember. But this meeting, no staff. It was very clear. This is just a one-on-one thing. Obviously because Alan Simpson was who he was, I'm sure that in one sense I was still in tow, not with an HHS staffer, but with him. But they didn't want to have any staff there, which was fine.

Riley

Did you encounter any other significant opposition? I know there was only one no vote.

Sullivan

Not really. I did meet with some of the Senators in a Republican caucus and [Jesse] Helms was there. He said, "I'm just not comfortable with you," and he made that very clear. Of course, I tried to be as cordial as possible and said, "This is my position," et cetera. As you know, when the confirmation did come, he was the one vote. But I then told my friends, "Well, that's okay, because I would have had a hell of a lot more explaining to do back in Atlanta had Helms voted for me."

Derthick

The Georgia Senators at the time were Sam Nunn and--

Sullivan

Herman Talmadge.

Derthick

Did they get involved at all?

Sullivan

Oh yes, I made courtesy visits to them. Of course they were supportive of me. As a matter of fact, they were both on my board.

Derthick

So you knew them before.

Sullivan

Oh yes, oh yes, right. They both, my appointment as dean was announced in April of '75 and I started in July '75. They were there for that announcement because the team of three people at Morehouse College really had worked to generate a lot of support for this, including support from our congressional delegation as well as people in the Georgia legislature. So when I went to Morehouse in '75, the next April, April of '76, we formed an initial board, the Board of Overseers for the medical school. Then in July of '81, when we became independent from Morehouse College, became our Board of Trustees. But Sam Nunn and Herman Talmadge were both members of that board that we appointed in 1976 and then became trustees in '81. So we knew them from that. They, of course, had been very helpful to us in Washington with legislation and appropriations there.

Derthick

On the one hand you weren't much involved in politics before, but in the normal course of your functions at Morehouse, you knew a number of public officials.

Sullivan

Oh yes, right. But the politics then was really lobbying for things that were important to the medical school, whether it was an appropriation or whether it was some bill on student aid or things like that.

Riley

Did they speak on your behalf?

Sullivan

Yes, they did. They both came and spoke on my behalf.

Knott

I'm going to exercise my prerogative as the chair and call for a break.

Sullivan

I'm glad you did because I was about to! [laughter]

[BREAK]

Knott

I'm wondering if you might tell us how much discretion you were given in terms of selecting your sub-Cabinet positions, your staff and so forth? How did that whole process work?

Sullivan

I was given a fair amount, as much as I really wanted. The reality was that being new to politics, I really didn't have a bevy of people in mind to appoint for various positions. So there were a number of people who were suggested to me or who had been recommended by the White House, and I indeed accepted a number of them. This was after meeting with them, talking with them, and forming my own impression, but I felt comfortable there.

The people who were my personal choices, who I felt were very important, were my chiefs of staff. I had three chiefs of staff during my four years there. Everett Wallace, who was my first person, and he played a very key role in helping me vet various people. Now, there were some people that we did not accept for a variety of reasons, whether it was a question of their competence or the chemistry with them or what have you, and didn't have any problem with them. But frankly, most of that went through my Chief of Staff, Everett Wallace. That is, he was the bad guy; I'm the good guy. We would talk about this.

Riley

You said that you did not accept--these were just people who were applying directly to you or were you getting names from the White House?

Sullivan

No, including names from the White House. First of all, there were a number of people on the list, some from the White House, people who had been active in the campaign and tied to this or that Member of Congress and that sort of thing. So we had a lot of suggestions, but we also were given flexibility. That is, I don't recall anyone where we said, "No, we don't want to put that person in this position, we have another option," where I was overruled. There were a number who were suggested that we did accept.

I can give you one example: Kay James was one person I mentioned. She had been in that group of people from the White House who actually were part of my orientation team. As I mentioned, she's the one who really schooled me in what the issues and the politics are in terms of abortion and so forth. She's a very active member of the pro-life community and so forth. She became my Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs. I felt comfortable with her, because first of all we got along very well. Again, she was one of those people, if there was some issue, she would come in and talk with me privately. I had not known her before. In fact, most of the people I really had not known from before.

There was one position I filled with someone whom I had known before and I had no problem putting that person in, but not in the senior position, Dr. William Bennett. Not Bill Bennett the drug czar, but another Bennett whom I had known because I had served on various NIH review committees and advisory councils. Bennett worked out at NIH. I wanted to have someone in the office who looked over appointments to various advisory committees and councils in the department at NIH, CDC [Center for Disease Control], FDA [Food and Drug Administration], Social Security, and others.

That was a major responsibility there because first of all, I wanted to get competent people, but also people who were in agreement with my policies. So I put Bill Bennett into that office to do that vetting and I didn't have any opposition there. But, say, Kevin Moley, who was my Assistant Secretary of Management and Budget, I met him for the first time--and oh, just most of the people. I didn't have any problem, but at the same time, I think it may very well be because I didn't really have a long list of people. I wasn't saying, "These are the people I want," because I had not been in political life before.

I also felt it important to have people who were knowledgeable about the political system and who also had their connections, because I felt I would need that and could use it as a Secretary who did not have that connection. My one connection was with the President, but all these others--and of course I knew some Members of Congress like Orrin Hatch and so forth. But I was very much aware there was a whole area of interactions and personalities and organizations that I really did not have any relationship with and so it would be to an advantage to have a number of people on my staff who did have those connections.

The main question was, would they be loyal to me? Also, were they competent? Because we didn't want to put someone into a position who was not competent, for obvious reasons.

Knott

The abortion issue surfaced again with the nomination of Robert Fulton as Assistant Secretary. Any recollections from that event? He has to withdraw his nomination, I guess, at some point due to opposition from right-to-life groups.

Sullivan

I remember that. I remember Bob, who was a good man. Actually, this is going back quite some time so my memory may be off, but it was expressed more broadly than that. I think it was about his policies on welfare and that sort of thing. What happened, there was Fulton himself who initiated the action to withdraw. That is, I didn't suggest that to him, but I know that he--I know there was one other person--Drew Altman. Drew Altman was from New Jersey. He had been one of Governor [Thomas] Kean's state officials there, because I wanted Drew to come into the department and he came down. He was interested, but again, he withdrew when there was opposition expressed to him too. In both of those instances, it didn't end up with me going to them saying, "I think we need to do this," but they did this themselves.

Knott

Early on, I guess the whole issue of your position on needle exchanges and the President's position caused another--could you tell us a little bit about that?

Sullivan

Here again, that was a position that I took. Frankly, this is one of those areas of compromise, and I can tell you I honestly was not comfortable with that, because I approached this from a public health standpoint. My thinking, and my goal, was to do whatever would be helpful to diminish the transmission of the AIDS virus as well as hepatitis and a few other things. But then the ideological issues that came in were are we promoting drug abuse by making availability of needles easier, and so forth. So this is one of those areas where already now having been bitten or surprised by this abortion issue, and having this issue flare up and looking at this, I decided that this was something I needed to get rid of this as quickly as possible.

So right, I had to alter my position there. Again, this was a compromise that I really wish that I had could have avoided having to make.

Knott

The White House was pressuring you to modify your stance? Is that an accurate--?

Sullivan

I guess you could say so. The pressure was not any pounding of the table, but I know there were many times in the press I was painted as having a big fight with either John Sununu or Dick Darman or what have you. The reality is that we'd be sitting like this and Sununu would say, "What the hell are you talking about? What's going on," kidding like that. So it was more persuasion and jousting and that kind of thing, because we were working to try and develop a relationship and be part of a team. It was really that kind of thing. Sununu would say, "What do you really think about that," and, "See if that's where you really want to come out, because this is a big problem," and all that sort of thing. So I was persuaded that way, that this would be the preferred position to take.

Knott

The press, the media perception of John Sununu was of somebody very heavy-handed, gruff, perhaps even arrogant. I was wondering if you would give us your assessment of John Sununu, the person you knew.

Sullivan

I guess it's fair to say yes, he's all of those things, but that's incomplete. He's also a very approachable guy and someone who also wanted to be very helpful. He, the big political operative there, knew very well that I was a political neophyte. He could have kept his distance and said, "We'll let this guy sink or swim." But he didn't do that, he really tried to be helpful there. I formed a very good relationship with him.

I mentioned the tobacco thing where he was supporting me on my side in his own way there. And he had a great sense of humor. We'd always kid each other about--let's see if I can remember some of the specific things here. I developed a very good relationship with Sununu even though politically, ideologically we were different. He was obviously much more conservative than I, but he was respectful of my position, even when he disagreed. I also felt that a number of times he was looking at the politics, rather than the ideology. Saying, "This is a bad issue to have out there in the press, we need to resolve this. It would hurt the President or it would hurt you," or something like that. "So how do we get this off the table as quickly as possible?" As opposed to, "We don't believe in that," or that sort of thing.

He was helpful. I, even today, have a good relationship with him. As you probably know, there's an annual luncheon, Christmas luncheon, the first Friday in December of every year. He usually comes to that. I'm going to miss it this year because I'm going to be out of the country with Tommy Thompson in Africa, but we'd see him and his wife there. So I had a good relationship. Meanwhile, out in the press, it was this knock-down, drag-out thing and it was really not that way at all.

I think again, fundamentally, I approached this as I was a member of the team. I didn't see myself as coming in there to overrule the President. I mean, this is the President, this is Bush's administration. I saw my role as trying to persuade if I had a different position and to be a success if I could persuade, and then being willing to compromise when I felt that I couldn't persuade and live with that. Here again, on something I felt that I couldn't, then I said, "Well, I'll just have to take the consequences." But I did not want to get out and take a position that would be directly contradicting the President, because I was there as a part of his team. My friendship for him also was such that I would not want to do that.

Knott

President Bush came into office promising a kinder, gentler administration. Were there certain actions, steps, policies that HHS pursued in light of that that sort of distinguished the Bush administration from the Reagan administration?

Sullivan