The global fight against HIV

U.S. policy to attack HIV/AIDS worldwide evolved after a dismissive and ineffectual start

Ronald Reagan was on the eve of celebrating his first Fourth of July as president when the New York Times published its first story about what the world would come to know as HIV/AIDS: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” appeared on July 3, 1981. “The cause of the outbreak is unknown, and there is as yet no evidence of contagion,” said reporter Lawrence Altman. At year's end, roughly 150 cases of the disease were recorded in the U.S.

Questions and answers in reporters’ exchanges with administration deputy press secretary Larry Speakes were short on seriousness and long on homophobia, the disease described as a “gay plague”. “Over 600 people have died,” said reporter Lester Kinsolving in 1982. “One in every three people have died, and I wonder if the president is aware of this.”

Questions and answers in reporters’ exchanges with administration deputy press secretary Larry Speakes were short on seriousness and long on homophobia, the disease described as a “gay plague”. “Over 600 people have died,” said reporter Lester Kinsolving in 1982. “One in every three people have died, and I wonder if the president is aware of this.”

“I don't have it. Do you?” replied Speakes as laughter filled the room.

In a press briefing the following year, Kinsolving offered his own joke: “Larry, does the president think it might help if he suggested the gays cut down on their cruising?"

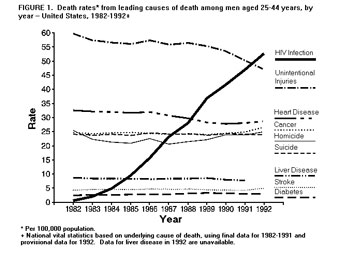

As for the Reagan himself, he didn't use the word “AIDS” in public until 1987, and his first speech on the subject came on April 1, 1987, when he called AIDS “public health enemy number one” and said, “we've thrown everything we have into it.” Still, it was up to Congress to add $203 million dollars to Reagan's AIDS research budget for the year, nearly doubling the total to $416 million. And though this funding had grown from $8 million in 1981, so too had U.S. deaths, which totaled more than 40,000. When asked about how schools should educate children about the crisis, the president replied, “I think that abstinence has been lacking in much of the education . . . no kinds of values of right and wrong are being taught.”

A hitherto unidentified virus from which the promiscuous man or woman suffered

The Miller Center's Ronald Reagan Presidential Oral History Project offers additional insights to the attitudes prevalent within the administration during the early years of HIV. Reagan's White House physician, Dr. John Hutton remembers,

It took several years to appreciate the gravity of this epidemic’s potential, the exact causal agent still not identified though it obviously could be transmitted by sexual contact or by receiving a tainted blood transfusion. Dr.[Robert C.] Gallo at our NIH finally announced that the infectious agent was a hitherto unidentified virus from which the promiscuous man or woman suffered, or the unwary surgical patient receiving a blood transfusion before we had the technology to test for the presence of the HIV virus in the donor’s blood.

There was little that the president missed that was newsworthy, and he had noted that this new disease had the potential to mushroom in epidemic proportions and that there was as of yet no known cure.

As is so often the case, an untoward situation is not drawn to our attention until someone who is well known becomes afflicted, and the actor Rock Hudson was one of the first to make such headlines. He had been well acquainted with the Reagans, and at that point the president then asked me about the nature of this new disease entity. . . .

Contrary to the opinions expressed by many, especially in the press, the president was fully aware of all the implications of the new disease and was very supportive of the activities directed at its isolation and the cure.

You didn’t dare, in that administration, talk about the use of condoms.

Otis Bowen, the secretary of Health and Human Services:

It was a very, very serious thing, and I think, earlier, the administration didn’t think it was as important as it really was. So they might have gotten a little less early on, but I did constantly try to get more and more for the AIDS research. I’d made predictions—just what is happening right now—about the 40 million people who have AIDS, and the devastation of the African young people. They’re losing thousands and thousands of them. . . .

And in the AIDS area, you didn’t dare, in that administration, talk about the use of condoms. I guess I’m kind of ambivalent here—I’m all for abstinence, but at the same time, I know that in the inner cities—not necessarily inner cities any more, every place—you’re going to have the teenage pregnancies developing, but the only program that the administration would permit was just don’t.

National legislation beyond budgetary allocations came in the next administration, that of George H. W. Bush, Reagan's vice president. One of his signature pieces of legislation, the Americans with Disabilities Act, included a provision outlawing discrimination against HIV-positive individuals. And he also signed the Ryan White Cares Act, which allocated funds not only to AIDS research, but also to AIDS patients and remains the largest federally funded program specifically for those living with HIV.

Nonetheless, Bush came in for strong criticism for failing to offer more leadership on AIDS; he only rarely spoke out.

Dr. Louis Sullivan served at Bush's secretary of Health and Human Services. He found himself caught between political calculations within the administration and the impatience building among activists outside as the following excerpts from the George H. W. Bush Oral History Project indicate:

My thinking, and my goal, was to do whatever would be helpful to diminish the transmission of the AIDS virus as well as hepatitis and a few other things. But then the ideological issues that came in were are we promoting drug abuse by making availability of needles easier, and so forth. So this is one of those areas where already now having been bitten or surprised by this abortion issue, and having this issue flare up and looking at this, I decided that this was something I needed to get rid of this as quickly as possible. So right, I had to alter my position there. Again, this was a compromise that I really wish that I had could have avoided having to make. . . .

In fact, this infamous San Francisco AIDS conference that I attended. Actually, I went to President Bush, I was going out for that conference, and I tried to convince him to go out with me. I said, "This would be a great thing if you were to do this, because the public perception is out there that we don't care." Quite frankly, I was pretty miffed at some of the AIDS organizations because they always had things in absolutes. That is, we had increased funding, we were doing a number of things—and again, certainly not perfect, the needle exchange issue was one—but overall, I felt that Bush was making a real effort. But he said, "Lou, I don't think I can go out to this. I'd just be a lightning rod. But you go, I'm sure you'll do a good job," and so forth. So that's what happened. . . .

Early on, when I became Secretary, so many places I'd go there'd be a line of pickets out there. What had happened was they had already prejudged this administration and prejudged me, which I really thought was not fair and inappropriate there. The first thing that Bush did, he increased funding for AIDS by I think a couple of billion dollars, including research funding. We appointed an AIDS commission that was actually chaired by Dr. June Osborn, who was then dean of the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan. She is now president of the Macy Foundation, where I just got this grant to do a history of the school. We worked a lot with that.

Even there, all of our moves and thoughts were suspect. We got [Erwin] Magic Johnson on the commission and when he came on, he had already been told by the people on the left that these were not honorable people, or you have to watch what they say. So he came on already with an attitude; we found it difficult to work with him. They demonstrated out on the NIH campus. They had smoke bombs, went into people's laboratories, calling scientists murderers, so I just thought that was inappropriate and uncalled for. People like Tony Fauci, I'm sure you know, really dedicated researcher there. Finally, as I mentioned, I'm trying to develop a relationship or build a bridge to people in the AIDS activist community. . . .

What I found in so many instances, people are intense in their feelings about this, in the same way about needle exchange. People say, "What you're doing is promoting drug abuse here, which is bad, and how can you do that." Really, so caught up in that, that they cannot see beyond that to say, "First of all, the evidence for that is not very good. But even if you were promoting that, is that worse than transmitting the AIDS virus here?" But I found, in my experience, that the ideologues are pure. They see things from one dimension, not from multiple dimensions.

U.S. Death Rate from HIV/AIDS, 1990–2019

“Over 150,000 Americans have died of AIDS. Well over a million and a quarter Americans are HIV-positive. We need to put one person in charge of the battle against AIDS to cut across all the agencies that deal with it.”

Candidate Bill Clinton's statement on HIV during a 1992 presidential debate with President George Bush and independent candidate Ross Perot promised additional action, but also echoed some of Bush's own rhetoric. “We need to accelerate the drug approval process," he added. “We need to fully fund the act named for that wonderful boy, Ryan White, to make sure we're doing everything we can on research and treatment. The president should lead a national effort to change behavior to keep our children alive in the schools, responsible behavior to keep people alive. This is a matter of life and death.” (Seconds before, Bush had argued, “If the behavior you're using is prone to cause AIDS, change the behavior.”)

Once in office, Clinton quickly ran into the politics of AIDS (see sidebar) when his announced intention to remove the ban to HIV-positive individuals traveling to the United States was met with thousands of letters of protest. (The only other disease preventing travel to the U.S. at the time was tuberculosis. Louis Sullivan, the Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Bush administration had also attempted to have the HIV ban lifted.) Needle-exchange programs for drug-users, shown to be effective in reducing transmission, were also controversial—Congress refused to allow localities to use federal funds to support the programs largely because of the false claim that they would increase illegal drug use. And Surgeon General Dr. Joycelyn Elders’ frank discussion of sex and sex education, led the president to fire her in 1994 when controversy erupted after her remarks during a United Nations conference on AIDS.

The funding of HIV/AIDS research, however, was by now long-established. Shortly after his second inauguration, Clinton addressed the subject in his 1997 State of the Union address: “Since I took office, funding for AIDS research at the National Institutes of Health has increased dramatically to $1.5 billion. With new resources, NIH will now become the most powerful discovery engine for an AIDS vaccine, working with other scientists to finally end the threat of AIDS. Remember that every year—every year we move up the discovery of an AIDS vaccine will save millions of lives around the world.”

During the shutdown of the government he had three hours and they called and said, “What do you want to do for those three hours?” I said, “I want to bring Fauci and Varmus and Helene Gayle, the experts on AIDS [Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome], and tell him where we are on AIDS internationally.” So we spent three hours with him talking about AIDS.

Donna Shalala, Clinton Presidential History Project interview, May 15, 2007

Indeed, the commitment to research had begun to pay dividends as U.S. deaths began to go down for the first time since the crisis, and in his final State of the Union, Clinton proposed exporting this success: “I also want to say that America must help more nations to break the bonds of disease. Last year in Africa, 10 times as many people died from AIDS as were killed in wars—10 times. The budget I give you invests $150 million more in the fight against this and other infectious killers. And today I propose a tax credit to speed the development of vaccines for diseases like malaria, TB, and AIDS.”

Since at least 1990, the death rate from HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa has significantly exceeded that of the United States and, unlike in the U.S., continued to rise until the mid-2000s.

When George W. Bush took office as the 43rd President of the United States, AIDS deaths in the U.S. were decreasing significantly. In other parts of the world, notably sub-Saharan Africa, the numbers were skyrocketing. The humanitarian crisis resonated with Bush's religious side. Peter Wehner, who served as one of Bush's key speechwriters, told Miller Center historians, “One of the biggest manifestations of the issue of religion and faith and its effect on the White House and on President Bush, which doesn’t get talked about very much, was PEPFAR [President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief], the global AIDS [acquired immune deficiency syndrome] initiative, and the malaria initiative. What I think a lot of people don’t understand, critics of the president never understood about him, was how religion affected him. It sanded off some of his rougher edges and made him a more empathetic person.”

Indeed, the ”compassionate conservative” approach Bush had promised, manifested itself in his significant commitment to going beyond HIV/AIDS research to prevention and treatment. Unlike his predecessors, Bush did not feel compelled to skirt the issue for political reasons. He addressed it regularly.

Indeed, the ”compassionate conservative” approach Bush had promised, manifested itself in his significant commitment to going beyond HIV/AIDS research to prevention and treatment. Unlike his predecessors, Bush did not feel compelled to skirt the issue for political reasons. He addressed it regularly.

Early in his presidency, he proposed a global fund to fight HIV and other diseases:

The devastation across the globe left by AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, the sheer number of those infected and dying is almost beyond comprehension. Suffering on the African continent has been especially great. AIDS alone has left at least 11 million orphans in sub-Sahara Africa. In several African countries, as many as half of today's 15-year-olds could die of AIDS. In a part of the world where so many have suffered from war and want and famine, these latest tribulations are the cruelest of fates.

For our part, I am today committing the United States of America to support a new worldwide fund with a founding contribution of $200 million. This is in addition to the billions we spend on research and to the $760 million we're spending this year to help the international effort to fight AIDS. This $200 million will go exclusively to a global fund, with more to follow as we learn where our support can be most effective.

The following year, Bush launched a $500 million initiative to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and during his 2003 State of the Union address, Bush announced a major new program: the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

Seldom has history offered a greater opportunity to do so much for so many.

Today, on the continent of Africa, nearly 30 million people have the AIDS virus, including three million children under the age 15. There are whole countries in Africa where more than one-third of the adult population carries the infection. More than four million require immediate drug treatment. Yet across that continent, only 50,000 AIDS victims—only 50,000—are receiving the medicine they need. Because the AIDS diagnosis is considered a death sentence, many do not seek treatment. Almost all who do are turned away. A doctor in rural South Africa describes his frustration. He says, "We have no medicines. Many hospitals tell people, 'You've got AIDS. We can't help you. Go home and die.'" In an age of miraculous medicines, no person should have to hear those words

AIDS can be prevented. Antiretroviral drugs can extend life for many years. And the cost of those drugs has dropped from $12,000 a year to under $300 a year, which places a tremendous possibility within our grasp. Ladies and gentlemen, seldom has history offered a greater opportunity to do so much for so many.

We have confronted and will continue to confront HIV/AIDS in our own country. And to meet a severe and urgent crisis abroad, tonight I propose the Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, a work of mercy beyond all current international efforts to help the people of Africa. This comprehensive plan will prevent seven million new AIDS infections, treat at least two million people with life-extending drugs, and provide humane care for millions of people suffering from AIDS and for children orphaned by AIDS. I ask the Congress to commit $15 billion over the next five years, including nearly $10 billion in new money, to turn the tide against AIDS in the most afflicted nations of Africa and the Caribbean.

Bush continued to promote American leadership on HIV/AIDS, addressing the issue regularly in his State of the Union. Inside the administration, he found many allies. Margaret Spellings recalled two in her Miller Center oral history interview: “I think he [Bush] just thought this was something that the great, big, prosperous United States of America had a moral responsibility to do something about. This was not something that germinated with him. If that policy has an instigator within the White House, it was probably Josh Bolten. A lot of us worked on it, and it was super top secret. I can’t believe we were able to keep it super top secret. People were stunned when it was announced as part of the [2003] State of the Union and recognized its order of magnitude. People could not believe George Bush would be taking on something like this, and it stayed the course and was another area where we had to bring Republicans on. Mike Gerson is another person who was very critical to the AIDS initiative. Not because he was a great scientist and knew how to develop an initiative, but as someone who saw the need for and could convey the importance of something like that. And Bush always looked to him for visionary policy . . .”

The political calculations surrounding the issue were no longer in evidence at the White House, opening up a whole new opportunity for leadership and policymaking. Needle exchange programs, once Congress's bête noire, began to find approval with a ban against them lifted in 2009. The president announced his intention to end the HIV travel ban—it, too, ended in 2009. In his final two State of the Union speeches, Bush stated simply,

- “Because you funded the Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the number of people receiving lifesaving drugs has grown from 50,000 to more than 800,000 in three short years. I ask you to continue funding our efforts to fight HIV/AIDS.”

- “[O]ur Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief is treating 1.4 million people.”

On World AIDS Day in 2007, the President did an event in Mount Airy, Md. to discuss the progress being made through PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. A woman from Africa known as “Auntie Bridget” was in the meeting. She got up and said, “I’m HIV-positive.” She was a nurse. She said words to this effect, “If it weren’t for the generosity of the American people, and for you, President Bush, I would not be standing here alive and well today.” You know, the hair on the back of your neck stands up. This is what President Bush did.

Kevin Sullivan, George W. Bush Oral History Project interview, November 2, 2012

The legacy of PEPFAR continues. In 2021 the State Department announced it had saved 20 million lives “with strong bipartisan support across four U.S. presidencies and 10 U.S. congresses.”