Transcript

Young

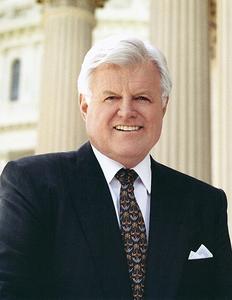

This is the March 28th session in Washington with Senator Kennedy. The subject today is healthcare, and Vicki Kennedy is with us once again, thankfully.

Kennedy

And Splash and Sunny [Kennedy’s dogs] will join us soon.

Young

They will join us soon. They have business in the kitchen or somewhere.

Kennedy

I thought maybe I’d start off initially with my association with the health issue and also the family’s association with the health issue and why it was a central force in my life growing up, and with my early days in the United States Senate—how the opportunity to become involved in it from a policy point of view, in many respects, goes back to my own observations about the importance of health in a personal way, but also in a way that exposed me as a young person to the policy considerations, and the impact that it had on me.

I have commented, probably earlier in our discussions, about the fact that my sister Rosemary [Kennedy] was mentally and intellectually challenged, and how she always was considered special in our family. As a small child, I found that I could play with children that were my age, or in many instances I would find that she was both available, acceptable, and desiring to play ball with me. We’d take a soccer ball and either play soccer, or bounce a lighter ball, like a beach ball, and play tag with it, or other children’s games. She always seemed to be willing to spend more time with me than the others, who were always distracted in playing other games.

I noticed that she had some special kinds of needs. I observed that early as a child. I didn’t understand it in the early years, and it took a while, obviously, to grasp the full dimensions of that, but I noticed that that was different. The regular kinds of childhood activities with childhood accidents when I was growing up were probably not different from other kinds of activities of large families.

I suppose the first major challenge that I saw was in 1961 when my father had the very serious stroke, which really disabled him in a very important way. He lived on for a number of years afterwards, but I saw the enormous—I was exposed to the dramatic moments of the time right after he had that stroke, about whether he was going to live or die, and also to the whole issue of being significantly disabled, and the corresponding actions of incredible care and loving attention that he was able to receive. The dedication of nurses and healthcare personnel, and the patience and the love and commitment of so many of those who worked with him, took an immense amount of time. Attention to this was a very powerful factor in terms of my whole observation of this part of my life.

He eventually went to the Rusk Institute in New York and got specialized attention from this fellow, Henry Betts, who is still alive and now runs an institute in Chicago. Betts was a junior figure to [Howard A.] Rusk, who was the national leader in rehabilitation. This was a first dramatic opening in my life, other than Rosemary.

I was elected to the Senate, and in the early years as my family arrived I was exposed to the power of asthma with a small child, Patrick [Kennedy]. We detected when he was two that he was a chronic asthmatic. He had the test that is given to children, where they have pinpricks along their arm—I think it’s 24 pinpricks—of different kinds of allergies. His arm looked like a nuclear meltdown; it just absolutely reddened, all of it. He was allergic to everything. My brother Jack [John F.] Kennedy was allergic to cat fur and my sister Pat [Patricia Kennedy Lawford] had allergies, and maybe the others had some, but I certainly noticed those as they were growing up. My brother Jack would come back to the Cape and would go into his room, and he’d come out about an hour later, storming mad, wondering who let the cat sleep in the bed while he had been away, or some cat had come on in. He’d be battling the allergies for the next several hours.

When Patrick developed it, we brought in medical experts at least once a year and sometimes twice a year, from around the country. They came in at nighttime. They would examine Patrick and talk with him, and then they would go off by themselves and have a meeting at a hotel, and then they would come over in the morning and brief me on their understanding of his condition, and their recommendations. Since he was chronic, there was a whole series of different types of medications that they would talk about, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. That continued all the way up through his graduation from Andover, even in his last year at Andover.

The last meeting was at the Parker House in Boston. He had some time off and my son [Edward M. Kennedy, Jr.] Teddy was going to take some time off, so the three of us were going to go away, and the doctor said, “Don’t go further than 35 or 40 minutes from a hospital.” So we went down to Key Biscayne, because we were 35 minutes away from the hospitals down in Miami. So, it was a major factor and a force as he was growing.

Later, in the early ’70s, we were faced with the health challenges that Teddy was facing with cancer of the leg. I always thought it was osteosarcoma, but I’ve been told it may have been chondrosarcoma. I remember very clearly his talking about and complaining about a bump on his leg, and how it wasn’t getting any better and it was getting sorer.

One morning I was headed to Boston and I was getting briefed about the various health meetings I was having in Boston. One of the staff people, Phil Caper, was also a doctor, and I had mentioned to Phil about the swelling. He examined Teddy and said, “You’ve got to get an X-ray on it right away.” I remember hearing later in the morning when I was up in Boston, about how they looked at the X-ray and saw the cancer, and that this was just enormously serious—life threatening. It was going to take immediate and dramatic action, which presented a wide range of both emotional and real decisions about the removal of his leg—the conversation prior to that time and the conversation after that time.

At the same time, my niece was getting married, Kathleen [Kennedy]. So this was a very emotional, roller-coaster period in my life. And then much later, my daughter Kara [Kennedy] found out that she had lung cancer. That was as a result of a picture that had been taken of her lung after—She had pain in her shoulder and was under medical attention for stenosis, and the very good doctor—

Mrs. Kennedy

Dr. [Jon] Wiseman. This was her internist.

Kennedy

—suggested that they take a picture of the shoulder. They found that she had lung cancer, and we had to move within a matter of hours. We went, later that afternoon, up to Johns Hopkins and had discussions up there with their medical team, which were very unsatisfactory. Then we had medical consultations with some experts and made a decision to follow a different route, which was surgery, which has worked out very successfully. She’s now four or five years free from any cancer.

So healthcare was something that had a real powerful impact. Also, in 1962, I remember the incident when my brother lost a baby to hyaline membrane disease. The child lived three days and then died at the Children’s Hospital in Boston. The interesting factor and force of all of this is that, if the child had been born two years later, it would have survived. The progress that was made in medical research would have permitted the child to survive. Here was the person who was the President of the United States, with all of the assets that he could have, and still was unable to see a positive outcome of this.

Within all of that, financial security was certainly present. It was present also in 1964 when I had the plane crash we’ve described earlier. I was able to get medical attention, initially up at the Cooley Dickenson Hospital, and then later at the Lahey Clinic that was located in Boston, before it moved down outside of Boston in later years.

I was exposed to the most extraordinary groups of doctors and nurses at the Lahey Clinic. Dr. [Herbert] Adams, who was the head doctor up there—there may have been a day when he didn’t come in and see me, but I don’t remember it. This included Christmas Day, New Year’s Day, the whole time I was up there. The commitment and the dedication of the doctors and the nurses, and the support systems and the professionals, was just breathtaking. I think it probably led me to the very strong commitment that I’ve always had, politically, to strong support for nurses, for support personnel, because I always recognized their indispensable role. The doctors, yes, but the support personnel for their patience and their time.

During the period when Teddy—Now we’re probably into ’74, so we’ll have to come back to how this intersected with the policy judgments and decisions. It was all within a few years of each other—the dramatic time that I had in the Dana-Farber Institute in Boston with my son Teddy. He had a treatment and we found out that he had this leg cancer that required the loss of his leg, and that’s a special circumstance that we can get into.

After we made a judgment about which regime we were going to follow—there had been several recommendations, and we spent hours trying to make a decision. What was interesting was that there were alternative ways of proceeding, and when the final decision was made, which I made, those who had different regimes were all very supportive. There was a real coming together of people who were all looking for a common resolution and solution to the challenges they were involved in. They all had different pathways, but nonetheless, once the judgment was made, they all were incredibly supportive.

It required that Teddy spend three days every three weeks at the Children’s Hospital in Boston, taking methotrexate, which is a medication that helps kill cancer cells, and this other medication [citrovorum] that helps to alleviate some of the adverse effects of methotrexate. That involved me giving him shots, which I did, both before he came on up to Boston and then right after he had finished the immediate treatment—for the next couple of days intensively, and in the night a couple of times, and then periodically, every four or five days after that.

What happened was, after two or three months, the NIH [National Institutes of Health] took this off the list of regimes that they were supporting for experimental research. The whole regime had been completed. NIH had enough material to wind up their conclusions. When we had started, my best impression was that there had been less than a hundred children that had completed the regime, but they had had—

Young

This was on an experimental research basis?

Kennedy

Experimental research basis by the NIH. There were probably less than a hundred that had gone through it, but they had had positive numbers on that. Before that, it was very tough; the survival rate was not good, you know, 15 to 20 percent. But after this it was 85 or 90 percent. So that was enormously encouraging.

After about three months of my being involved in it, they had completed the whole regime for it. While it’s an experimental drug, it’s paid for by the company or whoever is producing it. But once it’s stopped, the payment stops, and these families had to pick it up. Since it’s an experiment, none of the insurance would cover it, except mine, which is Senate insurance, federal employees’ insurance. The cost is $2,700 a treatment.

These parents would be in the waiting room—they had sold their house for $20,000 or $30,000, or mortgaged it completely, eating up all their savings, and they could only fund their treatment for six months, or eight months, or a year—and they were asking the doctor what chance their child had if they could only do half the treatment. Did they have a 50 percent chance of survival? A 60 percent chance of survival?

This was a very powerful presentation, in terms of starkness, about health and health insurance and coverage, and basically the moral issue presented here. We were all in the same circumstance. This is a very rare disease that could have happened to anybody. It happened to a United States Senator; it happened to children of working families. There was nothing that they could do about it, and they were being put through this kind of system. This is about as stark as you can get, in terms of the compelling aspects of this issue.

A secondary issue that came up that’s related to the public policy is family and medical leave. I’d have to leave the Senate on Friday, and I could go and tell Mike Mansfield that I wasn’t going to be there. Just in terms of the votes, I wasn’t going to be there. It wasn’t a question about me not—I should be with my son and I was going to be with him, but I wasn’t going to lose my job because I was leaving, and I was getting paid for it while I was gone. I was getting paid leave on this.

At the time that we were debating family and medical leave, these families would lose their jobs if they didn’t show up, let alone get paid for it, you know? They would either lose their job for not showing up, or at least lose their pay, because they didn’t have the kind of coverage that we had in the United States Senate. That was at the same time that we were debating the family medical leave, and here you had about the most stark—the decision that parents have to make about whether to be with a child or—to have the job that they need, or the job that they love. I didn’t use the example of Teddy, really, during the debate, until the very end, during the final windup. After President [George H.W.] Bush I vetoed it in 1992, I sort of pulled out the stops on it.

Young

The experience with Teddy—the way I hear you talking about it is it really brought it home to you, personally. This is your first personal experience with that kind of situation, you know, with people having to spend themselves into poverty in order to end up—the choices.

Kennedy

Yes, the families in that setting, and talking about that, and seeing and feeling their emotion. The situation you could grasp very easily, but the emotion of that was something that was enduring and continuing, and I still remember it very clearly. I talk about it occasionally when I talk about healthcare, even now.

I spent six months in the hospital and five months in a Stryker frame—six months in all—when my back was broken, and I saw the dedication of the people. I knew it was costing a chunk of change for the insurance companies to cover my health insurance on it, but it didn’t present itself—the starkness, the compelling aspects—

Young

Pocketbook issues.

Kennedy

—about the pocketbook. And that has never left me. That aspect of it I’ve been constantly exposed to in the time that I’ve been in the United States Senate, and I go back to it on many different occasions, on the different hearings or things that follow this. One very important set of hearings that I had in the Senate were the hearings in the—We’re getting ahead a little bit but it’s probably worthwhile pointing out because it’s close to this subject matter.

In ’78, when we took the committee across the country, we tried to match up, in the hearing, the panel that we’d have. We’d have one panel and we’d have probably ten witnesses, but we’d group them so that there were five subject matters. We would have the way that the United States covered the particular illness, and the way the Canadians covered it, just to present to the American people the difference, you know, how the systems were in terms of real life circumstances. We’d have what were common experiences in the particular areas that families would be affected.

One of the most dramatic that I still remember so clearly was in Chicago. It was two families that had children who had spina bifida. In the U.S. family the mother was a schoolteacher and the husband was a construction worker, and they made a good chunk of change and had a very good life. There was one other child in the family. Then the mother had to stop teaching school to take care of the child because it got sicker and sicker. And then, because the mother got run down, the husband quit his job. They went through all their savings looking after this child, and the result was that the state was going to take away the child because the parents could no longer take care of this child. You had the mother and the father completely distraught about this. This was out in Chicago.

Then—this was very interesting—in Canada, the family with the spina bifida child, and they were taking care of it. While the mother had the spina bifida child, she had a family of four: three of them had graduated from high school and were out. She had one left, and she went and adopted three children who were disabled, and the governmental system paid for taking care of them—the food and the clothing and a stipend for the housing. You’d ask the mother why she took in these children and the mother’s response was, “I want to teach this child what love is all about.”

You had this dramatic contrast between the system that was just wringing the last ounce of humanity out of a family, and this other system that was dealing with it in a humane and decent way, and a more economic way in terms of the whole process. I mean that was just one—I can remember it just as clearly as I’m here. You know, these things don’t leave you.

And they are just as much out there today. You could have that same hearing today in Chicago and you could have it in any city in America, and have the exact same results on it, and that part has even grown, because you’ve got so many more—I mean, I use the example of the parents that hear a child cry in the night and wonder whether they are $485 sick, because that’s what it costs to go to an emergency room. They listen to the child. Is the child getting better or sicker? They wait until the child finally goes to sleep and wonder whether the child is going to be worse in the morning, because they can’t afford the $500. Or they take that $500 that they put aside to educate their kids, and it’s gone. And that is what’s happening all across the country.

So this aspect of health and the coverage and the rest of the policy issues are all rooted in a very early association and personal attachment. Finally, the policy issues come and attach themselves in different ways, and we can talk about that. You can talk about how people who have a preexisting condition—Even Teddy, who has had cancer—even though he’s 47 years old, he could not get an individual insurance policy today, because he’s had cancer, even though he’s as healthy and strong as can be. He could not go out and buy, in the United States, an individual policy. That’s the way it is. That’s the way the system works on this.

Obviously, he’s in a group—but then, if he left that group, could he still carry on through? You didn’t used to be able to, but you’ve got the [Nancy] Kassebaum bill now that says that they can’t discriminate against—if he’s gotten into the system, they can’t knock him out. But that’s sort of a feature of the policy. We can go back now to a time when we got started in the health policy issues, but I think it’s at least of some importance and consequence how we got into it.

Young

Before you go into that, while you’re still on the injustice and the suffering, did you feel, at those hearings or at any time during your career, that when you pointed this out—the actual human condition that people face and families face—that people paid a lot of attention to that? Did it get traction, as they say? Or did people say, “Well, how unfortunate,” and then go their own way?

Kennedy

I think people understand it. A continuing aspect is that people are very fair, and they’re rather empathetic and sympathetic about their neighbors. This is something that they understand and they feel, and they appreciate. The question—you can continue to say, “Well, they may feel that, but if they’re going to be up against the wall and have to pay another big chunk of change, how long are they going to feel it?” I think there’s that kind of issue and question, and if the negative aspects are presented to them, in a way, they’ll be influenced by that as well.

The idea of fairness in this country still has a ring to it that’s sort of overwhelming, such as when you’re talking about increasing the minimum wage, even among people who all do better than that. People understand it and they’re empathetic and go for it. People understand this. And what’s interesting is that every family knows somebody who has had the circumstances that I’ve talked about, and they feel strongly about it. They are wary.

There are ways of trying to undermine that, which the opposition is very clever at. I find that the arguments are old and they’re tired, but they still have a ring to them: the idea that you’re going to have a bureaucrat in every hospital who will be making medical decisions, the idea that hospitals will close, that doctors will leave, that the expenses will go on up through the roof, that you’ll have socialized medicine. All of these features can be manipulated in ways that can impact and affect people’s fundamental decency.

So, I suppose we can go to where we got into the policy issues and questions, if you think this is the place.

Young

OK. You got into this very early, and there are many people who have talked about Walter Reuther and the committee of 100. Reuther apparently approached you to serve on the committee, and they had kind of a lobby to push for this at that particular moment. Is this how you really got into it in the policy way?

Kennedy

Well the support for—I’m on the Health Committee and also on the Education Committee. The way the system works, obviously, is whoever is the senior one gets the choice of the different committees. It appeared to me that Claiborne Pell was going to take the Health Committee and I was going to be on the Education Committee. I liked Senator Pell.

I had been in the Senate for five years, and although that sounds like a long time, in time of the Senate it was a short time, and I’d been out a good chunk of that time because of the plane crash in ’64—I’d spent’64 out of it, and ’63 was a difficult year. Then we had the ’68 campaign and that was a difficult year as well. But now, in ’69, we’re looking at both the committees and where I’m going to spend time and how I can be the most useful and productive.

That was the time of Walter Reuther, whom I had known from the time he had been supporting my brother. He was very significant and a major figure, and highly regarded and respected. The UAW [United Auto Workers] had been a union that had supported my brothers, as well, so there was a good association with that. In a meeting up in Boston—and I don’t remember who had set this up, probably one of our supporters from the UAW set it up in Boston at one of the hotels—I had an extensive meeting with Walter Reuther about their proposals for developing a national health insurance movement. Would I be willing to be involved, active and help lead it?

That sounded like a great opportunity to me. They had demonstrated both effectiveness and commitment, and this was something that was enormously important, and could make a large difference. We were coming out of the period of the mid ’60s, where we had passed Medicare, in ’64 or ’65. We actually completed it in ’65, but there had been discussion, even in the Medicare, that this was only a part of the whole movement of comprehensive coverage.

I was aware of Harry Truman’s ’48 effort to try to get universal health care, and his disappointment, and that at least [Franklin D.] Roosevelt had looked at it in the ’30s and decided to go with Social Security rather than the health issue, and that it went back to Teddy Roosevelt’s progressive period, where he tried to move it along. So I knew the concept of the issue of national health insurance. I had heard enough, having been in the Senate during the ’64 battle, and in ’65, to know that we had taken a chunk of this but we hadn’t done the whole job. I had seen the success that they had had in ’64 and ’65 and thought that this was both a great opportunity and an area of very important need.

Young

You said that Reuther wanted you to lead the effort, or help lead it. There is the story that he helped you become head of the Health Committee. [Ralph] Yarborough had been there, and as you mentioned, Claiborne Pell was slated—there are some amusing stories there. Are they true, as far you know?

Kennedy

Yarborough was defeated. I thought Yarborough was on the Education—the subcommittee. So that probably opened up the Education Committee. He was out, so that created an opening. How Claiborne—he had been for a long time interested in education, because we had just completed the higher education bill.

Young

It was a natural?

Kennedy

It was a natural that he would—I don’t know whether he wanted to go over to the Health or not, but in any event this opened up. At that time, these outside influences were considerable. Labor had a real influence on people getting on the committees, and who was going to be on the different subcommittees. They couldn’t overturn, or break a lot of eggs, but if there was a fairly even kind of justification, they could influence.

Young

Now we’re going.

Kennedy

So, we had Reuther, and I was able to get a number of people who were co-sponsors of it, Democrats, and only one Republican. The one Republican was John Sherman Cooper, who was not a liberal Republican. I never could quite understand what that was really all about. I was a great pal of John Cooper. He was closest to my brother Jack, and a dear, dear, valued friend in the Senate. I’ve told the stories about John Cooper and the respect people had for him. But when we put in the bill the first time, we had one Republican and it was John Sherman Cooper. People sort of gasped.

On the Democratic side, we had a good chunk—I don’t know, probably 30 to 35 Senators on there and we were on our way. I put it in with a Congressman who was on the Ways and Means Committee, Jim Corman, who was a very bright, smart person, who had worked with Reuther and had been for comprehensive, single-payer. This is basically the single-payer program.

Now we’re into the period of the ’70s, and we’re trying to think about how to go through—We go through a whole series of different maneuvers over a very considerable period of time. We’re trying to see how we can build a coalition and how we can expand the breadth of our support.

One interesting phenomenon during this period of time is that Wilbur Mills, who was the Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, an enormously powerful position, was interested in running for President. No one gave him much of a chance, but he thought that the way to do it was to be for national health insurance, and so this opened up—To have the Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee being your ally on this was a very significant and important opportunity.

He and I got along fine. I had never been all that close to him, but he respected my brother Jack, and they had some mutual friends. So we had this sort of dance, trying to get him into the program. He wouldn’t go for the single-payer program and through all of this period, we’re sort of adjusting and changing. The Republicans, even when they came our way later on, were always sort of holding back and always tipping the tide to the industry—and the industries that were most effective were the insurance industries and hospitals—during the series of debates.

We suffered a very serious setback as we started to move ahead in the early ’70s, with the loss of—Walter Reuther was killed in an airplane crash. And also by the fact that Wilbur Mills got himself in trouble.

Young

Well, Labor pulled out when you went—Andy Biemiller?

Kennedy

When we went with Wilbur Mills, they thought, in the ’74 period, ’76 period, that they were going to have a veto-proof Congress. They said, “Why are we making accommodations and adjustments now to try and get a bill, when we can wait, and we’re going to pick up all kinds of seats in the House and the Senate, have a veto-proof, and therefore, we’ll be able to get a much better bill?” It’s always the classic kind of circumstances, where you’re holding out for the perfect, rather than dealing with the good. This was the first example.

The next example—and we may not want to get ahead of ourselves—was during the period where [Richard] Nixon was just getting started on Watergate, and getting impeached—the process of threatening for the impeachment. Mel [Melvin R.] Laird, who was very close to President Nixon, and had also been on the Ways and Means Committee or Appropriations Committee, was a very smart person and had talked to Nixon. They believed that if this was such a powerful issue and one with such popularity, that it might even save Nixon from impeachment.

We had conversations with Mel Laird about how we were going to proceed. He had basically the concept of pay-or-play, which we would grab today if we had that opportunity, which meant that you either have an insurance program for your people or you pay into a fund. That concept is used in Europe in their industry, not only for health but also for training programs. They have training programs with the requirement that you either have to train a certain percentage of your workers in a continuing training program, or you have to pay into a fund that will continue to train them, and so you have an ongoing and continuing training program.

That was what we called the school-to-work program, which we actually implemented here during the [William] Clinton Administration. But the only way we could get it passed was if we sunsetted it, and we sunsetted it, and the Republicans wouldn’t vote to continue it, which was a good program. Now we’re into the ’70s, where Nixon gets impeached, and so that whole effort collapses.

Young

How close do you feel it was? You had mentioned early about trying to get a coalition together that could push it through. You got give on the part of the Nixon people, or at least there was an expression of some interest because it might help him out in a time when he needed it. But Labor had sort of stood aside. Does that mean the coalition never withstood in the first place?

Kennedy

Well, it really never came enough together, because when Labor sort of took a walk on this, that was a setback. I thought we still might be able to get it pulled together with the Republicans and enough Democrats on it, although Labor was teed-off at it. There was some division within the Labor movement on it.

You know, it was always very interesting with Labor, because there was a great dichotomy. You had industrial unions that wanted it, because a third of all of their premiums that are paid are being used to cover somebody else. So those are lost wages. They understand that their economic interest is in getting universal coverage, because then they weren’t going to be picking up and paying for people who didn’t have it. So that made sense. They were going to increase their wages and have a stronger position, and it was sort of the right thing to do for other workers. They liked it. That’s one part of it.

The other part of Labor said that they don’t want any part of this program for universal coverage, because they want to be able to deliver it as part of their organizing. They want to be able to go out and say, “Join my union because we’re going to give you health insurance.” They’re not as interested in universal coverage, because that’s going to take away a major kind of an appeal that they would have.

So you had lip service. You had some who were very strongly for it—the industrial unions; others who said they were for it and really were not; and others who basically sat on their hands because they said, “Why are we going along with this Kennedy proposal when we can use this as an organizing tool? We’re losing members, and we’re losing support in terms of working—this is a key way of getting it. It’s got a lot of grassroots support, and we use it as an organizing tool.” Of course they didn’t use it as an organizing tool. They didn’t do the follow-up on it. Andy Biemiller and [George] Meany and the other follow-on leaders were not interested really, in following—

Mrs. Kennedy

Kirkland.

Kennedy

Lane Kirkland. Lane Kirkland was more interested in the international Labor movement. I mean, he was somewhat interested in solidarity. He did do some good work in terms of the support of international, but he wasn’t really interested in this. We had a hard time keeping all of that moving.

Young

This jumps ahead too much, but has Labor’s position fundamentally changed from what it was then—their circumstances from then to now? Do they still have that—?

Kennedy

They still have that dichotomy. You know, it depends on the unions, about where they are. Some of them have got other issues that are as important, if not more important, in terms of the narrow Labor issues. All of the railroad unions were concerned about Amtrak—that’s 31 of the unions who were all concerned about—that’s their particular part of it. The building trades were concerned about independent contracting. And they’re worried about immigration and this kind of thing that they get on the health.

The number one issue for Labor today is the Employee Free Choice Act, to permit them to have card check-offs for organizing. That’s really the most powerful, although you still—this is one of the four or five issues that they’ll list, but they’ve got other issues as well.

In a number of areas there is a heightened interest on the part of Labor, because in an increasing number of these negotiations they are losing ground because they are having to pay higher co-pays and higher deductibles. Therefore, it’s becoming more of an issue at the bargaining table, where it was sort off the bargaining table for years. Even in the UAW, it was never—all they would do is continue to make progress in coverage, and now they’re in a gradual kind of retreat.

They made this macro deal recently, where they developed a foundation to offload some of the expenses—a rather complicated financial deal that helped them get out from some of the legacy costs on it. But I’d say that now, in many more union disputes, healthcare is front and center, but they still care about some of these other issues.

We could go on in terms of where we are in the ’70s. We’ve gone through pretty much on Nixon.

Young

Were you getting Republicans coming aboard at all during some stages of that? Was [Caspar] Weinberger seriously interested?

Kennedy

He was a spokesman and secretary, but he really was strongly against doing anything that was going to deal with the payroll tax. That issue had been somewhat opened, about whether we would raise the limits in terms of the people who were paying or not, as a source of both health insurance or long-term care. He took a very strong position that they wouldn’t do anything at all on that, which meant that we weren’t going to be able to get revenues on it. So it was basically put off and put over.

Young

So the possibility of a compromise on the play-or-pay lost you Labor, and then stopped things with the Republicans, so that sort of left you high and dry.

Kennedy

Yes. I think that’s probably where we were in the mid ’70s. The next time we come back to this is with [Jimmy] Carter.

Young

What’s the story there?

Kennedy

Well, basically, in the ’76 campaign, the candidates who were running then—[Morris] Udall was running—I should have the four major candidates that were running at that time.

Young

Was [Henry] Jackson involved?

Kennedy

Jackson in ’76. I don’t know whether [John] Glenn was in there. I don’t know if [Walter] Mondale was. We had Glenn and Udall and—

Young

There were four.

Kennedy

Yes, there four candidates.

Young

And they were all in Congress, as I recall.

Kennedy

Yes. Three of them were strong for universal comprehensive coverage, effectively a single-payer or universal coverage, except Carter. Carter refused, during the whole course of the campaign, to take that position. He had reasons that I don’t know. I guess he wanted to do everything on his own on this thing. He sort of relished the idea that he didn’t have to make a commitment on universal comprehensive coverage. He had stated, in the course of the convention—The convention in ’76 had a good plank for universal coverage, which he claimed to support and which was written mostly by the people that supported—by the UAW people, and Leonard Woodcock and Corman, Woodcock being the head of the UAW then.

But whenever he was asked about it—he talked about healthcare; he talked about coverage; and he talked his way around it. You know, he used artful words all the way through this. I campaigned for him and appeared with him on a number of occasions, but he was never—When he got the nomination in ’76, I think it’s probably the only convention I didn’t speak at. He wasn’t all that interested in me speaking at it. He wanted to be separated and clear from the Kennedys, and he made that somewhat clear.

Young

I don’t understand that. Can you shed any light on that?

Kennedy

I don’t quite understand that either.

Young

Was it a feeling of competition?

Kennedy

It just didn’t make a lot of sense. When he got elected, the question was—he had given certain indications that he was going to be for it, but that he wasn’t going to be for the bill that I supported and the Democratic left supported. Then the question came about what the timing was going to be. As we were moving along during that time, he kept delaying putting forward a proposal, and it developed that he was going to put forth principles but wasn’t going to put forward legislation.

He talked about doing cost containment. Health planning was going to be first, and then he was going to try and do cost containment next, before we had coverage. Then it eventually kind of deteriorated, where he was getting caught up with the high rates of inflation, economic challenges, and he was going to support a step-by-step program in healthcare, where he could take a step, and if other economic indicators didn’t come out quite right, he could either delay or pause before they’d take the next step.

Congress was going to have to take action again for the second step, so what we were faced with was that we were going to have not just one battle, but a series of battles for the next four or six years, and passing every two years an add-on in terms of health, which was a nonstarter.

Young

Political, I guess.

Kennedy

That is, effectively, where he was going. And that was effectively what the debate was about, and that was effectively the reason for the division. It was couched in a lot of different ways. You read through the notes and the exchanges, and he is saying you can do this step-by-step in different ways. You can say, well, we’ll step it up but it will have to be a vote of disapproval rather than approval, trying to change it.

So we were talking about all of these intricacies about how to do it, but what was happening was that time was going by. The people who were concerned about the economy were catching his ear. He had said that he was going to try to do an energy bill first, and then when that didn’t go through, he still was back to these principles, and that was the real delay. So we failed.

Young

Do you know if—Stu Eizenstat was his domestic advisor at that time. What I wondered was, do you think the idea was ever floated to him to go for the principles and leave it to you and the others who are for this, to try to see what you could get with his endorsement, rather than try to manage the details of how we’re going to do this?

Kennedy

I don’t think he was into it. The problem was he didn’t really want to stand up on it, and you couldn’t—there’s a difference if you’ve got somebody who wants to, someone who is serious about giving certain principles and support to those as it moves on along. He wasn’t. He was completely ambiguous about it and resentful of the pressure that was being put on him for doing this. The little sidebar on this is that he eventually fired [Joseph] Califano, which halted any of the progress that we were beginning to make.

Young

You had some very direct exchanges with Carter.

Kennedy

Well, let me come back to what I was going to say about Califano. Califano and I both went to the Holy Trinity Church here when our children were small, and part of the service was that, after 9:00 or 10:00 mass, the children would go down for Sunday school, and they would have a discussion there for the grownups. They’d have one of the Jesuits who would come over and lead the discussion, and they were always enormously interesting, very interesting, very gifted, talented lecturers. There were always a couple hundred people who were there with their children, and then, at whatever time, an hour later, you would break up and hook up with your children and drive them home.

Carter found out that Califano and I were going to the same meeting, and he heard that they were just talking in general terms, and he became enormously suspicious of Califano. Califano never trimmed on Jimmy Carter’s principles. Wherever Carter came down, he stayed. You’d talk a little bit about it here and there, trying to glad-hand your bid on some of these kinds of things, which I understood. But he never trimmed, never played a game on that thing, and he stayed absolutely consistent.

Carter fired him because he thought he was becoming too friendly with me on this, there’s no real question. And once he left—I mean, he was the only one who really understood the healthcare issue—it was gone. Eizenstat was, I thought, a positive. He wanted to be helpful in trying to bridge the gap. Califano didn’t want to have a split. It’s kind of interesting, in these notes, the extent that Jimmy Carter said that he didn’t want to have a split with us.

Young

Yes, I’ve noticed that.

Kennedy

He mentions in these notes that he didn’t want to split with us, but there was no question. This is Carter speaking: “I want to work with you. I know that we are not going to have a chance to get any bill passed unless we have your help and your support, but I’m facing serious problems with this. What I would like to do is to talk to Stu first thing in the morning and get back to you, to ask you to come down here and explain why it is in the interest that we do this before the election.”

He’s demonstrating—but he had made the judgment and the decision that health was going to be put aside, and that was after we had gone all the way through all of this part, and after he made several commitments to us on that part. He was just backing out of that. I mean, he was facing extraordinary challenges on this, but he just wouldn’t move on it, just wouldn’t go on it.

Young

I think by that time—they got after him for over-promising, and he says in some of those notes, “I can’t take on another major commitment at this time.” But it is an interesting exchange in that memo. So now you don’t have—so he’s another Nixon?

Kennedy

The basic point where it broke down was—He used the technique of saying that he had announced principles and that would be their commitment, and then he’d move on from there. But you have to announce as part of the principles whether you were going to have one bill or several bills, and he would not make it clear that it was going to be one bill, and he wouldn’t make it clear that, even if it was going to be one bill—We talked about, well, then it’s going to have to take the Congress to unwrap it. He wouldn’t go that far.

We gave him that kind of alternative to preserve it, but he wouldn’t go there. He would only say, “We’ll get one bill and if we meet the economic points test further on down, then we’ll submit it so that it can have a second phase, and a third phase, and a fourth phase.” And that was the break. That was just completely unacceptable, in spite of the fact that we had a lot of conversation about how to do it and when to do it.

We had the attention, obviously, of Carter. He understood that the spending on health care was not unrelated to the spending on inflation. But there’s a way of dealing with both of those, and he wasn’t prepared to do that.

Young

How was the coalition at the time you were trying to get Carter to move?

Kennedy

We were together then.

Young

Was it pretty good? Was Labor there?

Kennedy

Labor was back with us, because they had been instrumental in writing the Democratic plank, and Carter committed to the Democratic plank. They had the expectation—and I was very happy with the Democratic plank, so it looked like we were all back on the same wavelength. Then there were these series of different meetings with Leonard Woodcock and Carter. Woodcock would say, “He’s equivocating,” and then Carter would say, “I’m going to put out the principles,” and then he wouldn’t put out the principles, and then the principles that he announced were not adequate. So Labor lost interest and basically gave up on it.

Young

Was it at all bipartisan support then in the Congress, or was it still basically a Democratic?

Kennedy

Basically a Democratic. At that time we were—I forget, but we had an overwhelming majority.

Young

A very large majority.

Kennedy

A very large majority. There were probably three or four Republicans who had some interest in it. Bob Dole was sort of—and [John] Chafee had some interest in this, but when it came down to trying to work this thing, they basically abandoned their positions pretty quickly on this. It became pretty clear that Republicans didn’t want to—and the various groupings in the Republicans were against it, so they opposed it.

Young

Then [Ronald] Reagan comes in. Did you have more on Carter?

Kennedy

No. I was just thinking about [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan and the Finance Committee, but the real tension that we had with them was later on.

Young

Yes, that was with Clinton. When the idea got nowhere with Carter, and Reagan was then elected, did you think, It’s dead for the next four to eight years? Was that your feeling? It’s the last chance until another time long away?

Kennedy

Yes. There was going to be no real opportunity to move it during the Reagan period. That’s when, as you might remember, I went from the Judiciary Committee back to the Labor Committee because there was going to be the massive assault on all the domestic programs. And, at that time, there was going to be the consolidation of all the block granting—all of these programs, some of which were block-granted.

It seemed to me that it was just going to be important then to try to hold on to where you were in terms of all of the domestic programs, and that’s primarily what we were engaged in. We were involved and active in other issues then. We went to South Africa, and also we had Chile, and we had the arms control issues where there was some of the back-channeling with Reagan. But on the domestic, we weren’t going to get anyplace at all, and that was very apparent to me. What happened is he continued to have the continuing loss of coverage in health insurance and continuing increased expenditures. The indicators were still going the wrong way.

We did have, in ’67—we’ve gone way past that, but we did neighborhood health centers.

Young

Yes, yes.

Kennedy

That was passed. That was a big deal. It was about $35 million. I don’t know whether we’ve covered that.

Young

You’ve mentioned it before but haven’t really talked about it.

Kennedy

That was a major health issue, and it’s even bigger now because it’s about $2.5 billion a year and about 17 to 19 million poor people get healthcare through the neighborhood health centers. It started out with two centers: one in Columbia Point, Massachusetts, and one in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, in the poverty program. It was initiated by two doctors from Tufts: a fellow named Jack Geiger and a fellow named Count Gibson. I went with them out to the Columbia Point system and later on to Mississippi.

At the Columbia Point system I became convinced about the possibilities for the neighborhood health centers, and offered this as an amendment on one of the pieces of legislation that was coming through—I can’t quite remember—some health bill that was coming through. It got to the conference, and Adam Clayton Powell was the Chairman of the conference, and he said, “Well, the last item on the agenda is this program by Senator Kennedy, who is over here now. What’s that about? We want to wind this conference up.” So I explained what the health centers were about, and he said, “Well, how much money is in there now?” I said, “There’s enough money for three of them.” And he said, “Write in the legislation to put one in my district, and you can put the other two wherever you want. Is there any objection on it? Have we wound up the business of our committee? The conference is ended.”

And that was the beginning of the health centers, and that program we’ve stayed after. I think I’ve spoken at every one of their annual meetings since that time. They’ve just done amazingly well. One of the principal reasons that it has done so well is because of the makeup of the advisory committees for each of the boards. The makeup is between consumers and providers, and the balance is such that it’s reflective of what they want in that community. So, in the South End, they want AIDS treatment and testing, and in the North End of Boston, they want dental care, because the water is bad, or whatever it is. They’ve got sufficient flexibility within that, but it still maintains a comprehensive range of services. Now they’ve got associations with these hospitals, which has strengthened all of them in a very important and significant way, and there’s sufficient flexibility so they can do that. It has all been welcomed.

We were facing a period, when Reagan got in, that they were going to be put into a block grant on the preventive healthcare. Orrin Hatch was supposed to be the negotiator for the Republicans, and he just wasn’t interested. You had to go over and sit for about 12 hours, and go over each health plan and figure out where it was going to be put in—enormously tedious work, which we did. [Howard] Baker finally took it over because Orrin Hatch wouldn’t do it, and he said, “We’ve got to end this whole process. We could be here for another week.”

So I said, “Well, I’ll tell you what we’ll do. Instead of having the four block grants, say that there’s nine block grants, or ten block grants, and I’ll say, ‘This is a victory for Ronald Reagan because he’s got these things block-granted, but we’ve been able to preserve—’ and you can say the exact same thing: ‘We wanted to block-grant it; we’ve got it block-granted; and we did have to have a few more block grants to take in.’” And that was basically the architecture of the press conference that we had. One of the things that we saved were the neighborhood health centers.

That was in ’80. I don’t know where we want to go—

Young

Well, the Clinton is the next big—the Clinton years. Why don’t we take a break now.

Young

Now, did you want to go to the Cancer Act, or do you want to go to Clinton and then go back to some of the other things?

Kennedy

Maybe we’ll do some of the others and then go through Clinton, or we can do Clinton and then do those.

Young

Well, let’s start with the Cancer Act.

Kennedy

In Massachusetts, in 1961, I was asked to be the Chairman of the Cancer Crusade in the state. I had not been very much involved and interested in cancer, but I had been involved or engaged in Massachusetts, in this proposal. They had a very distinguished group, including a fellow named Sidney Farber, who the Farber aspect of the Dana-Farber Institute is named after, and he is a leading researcher. He’s a very inspiring figure. And they had a leading Republican state chair, who is a very decent fellow. We traveled for probably 40 nights, meeting these volunteers.

It had been suggested that this would be interesting, but it would be enormously valuable and worthwhile in terms of the politics of it because you’re meeting these groups and meeting them under very good circumstances. I traveled all over Massachusetts, meeting all of the people who were involved in the Cancer Crusade, and they were just a very impressive group of people who were very emotionally involved in that.

After I was elected and came to Washington and was on the Health Committee for a very short time, Mary Lasker, a distinguished woman philanthropist of the Lasker Foundation, spoke to me about doing a “war on cancer.” She said that we had to re-do the whole Cancer Institute to make it more effective in dealing with the challenges of cancer; to have their own budget, for example, and their own administrative way of proceeding, and being able to target more resources to clinical research.

They had a number of other recommendations, and they had these recommendations as a result of a panel that had been set up by Mary Lasker, that was made up of very distinguished individuals. It became what was known as the “war on cancer.” The New York Times was strongly opposed to it, thought we were targeting too much of the money, and that you couldn’t just legislate solutions to cancer. So it was lively and controversial, but I thought we had a strong case. We wanted to get this passed and it looked like we had a good chance of getting it passed. Nixon was really the figure that was blocking it, and it was entirely personal; he would not do it if the bill had my name on it.

One of the people who was very involved in this effort was a fellow named Benno Schmidt, a very successful financier from Texas. He had handled several different fortunes and had been very successful. He was enormously committed and very knowledgeable about the cancer issues, and he was a very strong supporter of Nixon. He went down and talked with Nixon, and finally he called me and said that if I took my name off it, Nixon would sign it.

It was an interesting phone call that he had had previously with Jack [Jacob K.] Javits, who was the principal co-sponsor. Benno said, “Jack, Nixon will sign it if you and Kennedy take your names off it.” And Javits reportedly said, “I’m not going to do that, because I wouldn’t do it to my friend Ted.” Well, he would have done it to me at the time, but he didn’t want to have to drop his name off there too. I’m not sure whether he dropped his name or not. He may have still been able to stay.

I told Benno, “That that’s fine with me,” and with that, they put Peter Dominick’s name on there as the prime sponsor, who hadn’t been interested in it, hadn’t shown up for any hearings on it, had been rather cool to the whole idea, and it got passed. We had a signing down at the White House. At that time there weren’t many people that—the people on the inside were aware of what had happened, and one of the nice things is that Benno Schmidt wrote this all down in an essay that’s in the archives of the National Cancer Institute, in very considerable detail, about his conversations with Nixon and the rest. That was an interesting health sidebar.

One other small item in more recent times, in 2004, was the Family Opportunity Act. The Family Opportunity Act was legislation that I introduced with [Charles] Grassley and Congressman [Jefferson ] Sessions, who is the most conservative member of the House. He’s from Dallas, Texas, and he has a disabled daughter.

Under the current system, in order for a person to get services for a child, they have to work at the Medicaid level. If they work above that, they don’t get the services. You have people who are enormously talented, who’ve got skills and families, but they still have to sacrifice and work at the Medicaid level in order to get these services for their child. It’s enormously unfair.

This legislation permitted them to increase their salaries and still get their services. You pay more taxes, but it had a step-up so they could get several thousand dollars more and still maintain—and if they moved up, they gradually had a reduction in terms of the money that they got. So this was a winner for the families; it was a winner for the whole Medicaid because it reduced the amounts that were being drawn as these people made more money; and it increased the money for the federal revenue, so the taxpayers were greater protected. Except, under the budget it cost $6 or $8 billion, and you had to get that money—for what reason? You know, under the budget restrictions, so that slowed it down.

It was interesting that 90 percent of the heads of households that have these children are women, and there are about 600,000 in the country. The men leave and the women are the ones who take care of the children that are in the greatest—One of the very powerful arguments that we had on this is that it applied to people in the military. They couldn’t earn whatever—if you could imagine that, and the military wasn’t quick enough to make the adjustments on it. When people found out that this was happening to people in the military, they let this thing go—We never had a hearing in the House or the Senate; it was just done in the budget, passed in the reserve fund and money allocated within the budget, and it’s in effect at this time now. It made a difference to—

Young

Do you have co-sponsors?

Kennedy

Grassley and myself, and Sessions in the House. And that took probably five years, six years, to get that thing finally done. It’s not an insignificant part in these—coming out of order—we have two that are probably out of order: One was the program called SCHIP [State Children’s Health Insurance Program], initially the CHIP Program, the Children’s Health Insurance Program. This was modeled after the Children’s Health Insurance Program that was passed in Massachusetts, where a fellow named John McDonough was a representative and very much involved in it. It was successfully passed in Massachusetts, where they used the money that was part of the big tobacco settlement to designate it for health insurance for children.

I worked out legislation with Orrin Hatch, and the basic compromises on the legislation that were put in are why the opposition of President [George W.] Bush at this time makes very little sense: One, I wanted to have Medicaid standard for healthcare coverage for children, which is very extensive coverage because it has a lot of prenatal care. Well, it has not only the prenatal care, but it also has a good deal of preventive care. Hatch wouldn’t go for that. He said, “What we are going to have to do is describe the services, and we’ll say that the state has to provide a certain number of them, but we’re not going to require some.” Some of the ones that he wouldn’t require were dental care and eye care. We left it as an option in terms of prenatal care, I believe.

The second big compromise is we said that it would all be administered by private insurance companies, within a certain context. So he got the privatization and he got states making the judgment decision on the benefit part: the two big, big compromises, from our point of view, which is the compromise with the Republicans. He would be able to say this was a state program. And then they changed it from Hatch-Kennedy to—the Republicans had insisted that they call it a state children’s health insurance, to make sure it wasn’t going to be a federal program. State, SCHIP, they insisted on it and that was eventually dropped.

That had a lot of complications to it because the Clinton Administration opposed it because it had budget implications. President Clinton had made an agreement with the Republicans—Trent Lott—on the Budget, and Trent Lott wasn’t going to support the alterations and change, so they resisted and resisted and resisted it. It was effectively defeated once, and then we were able to save it at the very end. At the very end we had everyone pulling for it, including Senator Clinton. By that time we had Marian Edelman, who had been rather cool to it in the beginning. They thought we were going to draw money away from Head Start and other kinds of programs, and they weren’t—Hatch and I went around and spoke to all of these organizations here in Washington, together, putting in a very considerable amount of time and effort and energy to get that moving.

They had a very tumultuous meeting in the Finance Committee. I called up Orrin and laid into him that I thought he was selling out. He’s never forgotten this thing. Eventually, as the result of the meeting, they did save it, but they had to cut back on it a bit. But he has never forgotten my conversation with him.

Part of the problem now is that there are three or four states where they have given waivers on the CHIP program for parents to be involved, and there are some states that have more parents than they do children. That’s a criticism. The administration wants to cut all those out. The compromise, from the Democratic point of view, has been that they would change the match so the states had to pay more, but not to drop them.

The reason that the parents had come on is because they had been given a waiver by the Republican administration. The Republicans had given them waivers to let them to do these parents, and now the Republicans, including George Bush, are using that as an excuse not to support and fund the program. I mean it’s the most—and in spite of the fact that George Bush had said down in Texas—When they put the program in place, he was claiming all the credit in the world for it, and saying that he was going to double it in Texas if he was reelected.

So that is one of the very important health programs that we’ve been able to—

Young

How many would that add—a ballpark?

Kennedy

Seven million.

Young

Seven million more?

Kennedy

Well, seven million, and they had probably, if we took the additional—In the Democratic proposal they had about four million, and there would still be probably four million that would be left out. The question is at what income level do you cut people off? At what percent? The Republicans wanted it at 200 percent of poverty. We have probably five or six states, including Massachusetts, that have gone up to 300 percent of poverty. You know, you need to get it up to—300 percent of poverty is about $35,000 a year for a family of four; 200 percent is $22,000 or $23,000; and 400 percent is probably $50,000 in Massachusetts. But you’re still looking at a family that is hard-pressed.

Young

So this was done in what—’96, ’97?

Kennedy

This was done in ’97.

Young

After the collapse of the major initiative.

Kennedy

That’s right. This was done right after we also passed the Kassebaum-Kennedy bill. In the wake of the collapse of the Clinton program, we were looking for targets of opportunity. Senator Kassebaum showed some interest in passing legislation that said that if people had some disability and had insurance and were part of a group, that they could move and take their insurance with them, and they couldn’t have another group require that they drop their health insurance in the future. We had quite a go-around on that, because when it came to the floor the Republicans were opposed to it. We had a very tense period with Dole on this and accused him of refusing to call this up and went after him quite extensively on the floor.

Young

He was running or thinking of running for President at that time.

Kennedy

Thinking of running. One of the techniques that we used is that the Majority Leader would come out and talk about what the agenda was, and one of the things I did constantly was when he came out, I would challenge him and say, “Will you yield?” Well, he has to; he’s on the floor. He has to yield, and you’d say, “Why aren’t we taking up this bill? It’s bipartisan. Why aren’t we doing this? Why aren’t we doing that?” I just kept after him and after him and after him on this, all the times that he was doing this. Eventually, you build up—I did it on the minimum wage, with Dole and he eventually receded on that. And I did it on this, and he eventually went along with this and added rather a dangerous provision.

Young

Savings.

Kennedy

The health savings account, which is a way of permitting high deductibilities for people. It doesn’t help low and medium income working families. It’s only against catastrophic injury. But it obviously helps the very wealthy because they can afford the deductible, and if they have a serious illness then they are effectively covered. It’s enormously profitable to companies, and these companies tend to be all Republican.

They added a provision on the floor of the Senate in order to get our legislation through. I had to work out the resolution of it with Congressman [William Reynolds, Jr.] Archer from Texas in the House of Representatives, who was Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee. We had a number of meetings on it. He was a very principled and committed figure, very conservative. We had this sort of go-around where his mother was fascinated with my mother, so my mother signed a book for him, and he was very tickled with that. We enjoyed a warm personal kind of relationship and there’s no question that it made a difference. He retired from the House.

Mrs. Kennedy

I think you gave him your mother’s book.

Kennedy

I did.

Mrs. Kennedy

I don’t think your mother signed it; maybe you signed it.

Kennedy

That’s probably right. In any event, that was basically the Kassebaum–Kennedy thing. So we can go to Clinton now.

Young

This is I guess the third in your career to date.

Kennedy

Unsuccessful.

Young

The third major effort.

Kennedy

The third major effort.

Young

A window of opportunity, or whatever you want to call it. People are going to do a lot of comparison between Kennedy on this one and Kennedy on the other two—not just Kennedy, but the whole idea. You know, there are a number of people who say that this was just the death knell of the whole idea, that it’s not going to come again, but I’ll leave that aside. Didn’t you have very high hopes for getting this thing across under Clinton? What went wrong?

Kennedy

There was a great sense of anticipation and a great sense of hope that we’d finally have healthcare legislation that was worthy of its name. It was clear that he was for it, and that this was an important issue in the course of the campaign. It certainly appeared at the start of the administration that we were on track to get healthcare, but that hope gradually deteriorated and fizzled for a number of reasons.

Young

When he committed himself in the campaign—I’m thinking of Carter, who had committed himself rhetorically to it. Had you been advising Clinton on this during the campaign or earlier? I’m trying to get your impression of his degree of commitment to this, coming into office.

Kennedy

It’s difficult to measure. I didn’t know Clinton all that well, other than the casual political relationship with him. I mean, I campaigned with him. We started with a very warm relationship with the Clintons, starting really right in the beginning. We went out and visited the gravesite of my brothers with the members of the family, and he was certainly very responsive to—

Mrs. Kennedy

Can I say something here? I had an experience with him because I sat at his table before he was inaugurated, after he was elected, at Katharine Graham’s house. You were at a different table, and I was at Katharine Graham’s table where he was. Taylor Branch was there and there were several other people there. He proceeded to talk about healthcare that night, and he was very specific. I remember it like it was yesterday. He said if he couldn’t get healthcare reform, he didn’t deserve to be President. That’s what he said. This was like December of ’92. There was no doubt, I thought after that, that this was a deep commitment of his.

Kennedy

So this is sort of the start, and there were just a variety of different things that affected the whole effort in terms of the success of the proposal. First of all, there was the extraordinary amount of time it took for them to develop their particular proposal. Rather than taking any of the existing proposals and modifying them slightly and moving ahead, they wanted to do their own kind of healthcare proposal, and to take into consideration a lot of different suggestions and ideas. So they developed the taskforces that were set up to try to sift through various ideas and suggestions.

They had constant meetings, and they had a coordinator whose name was Ira Magaziner, an enormously gifted and talented person, a close personal friend of the President, a Rhodes Scholar and very successful person in the private sector, and very committed to this, as sort of a central coordinator. He was very friendly with us and we had a warm relationship with him, but nonetheless there was the establishment of these taskforces, and that delayed the—

Young

Why did they—?

Kennedy

I don’t know why they decided to go to a different proposal rather than taking what they had. They insisted that they wanted to bring people who had ideas about how to develop a better proposal. I think we had had good suggestions and ideas. There was a range of different options out there, but they wanted to have it very specific all the way through, rather than leaving some of these issues and questions for further development.

Young

And wanted to start it de novo, from scratch.

Kennedy

Yes, and they wanted to be very detailed about the particular functions of these different kinds of groups and pools, purchasing pools. They wanted a description of the size and the shape and what they were going to have in terms of different regions of the country, what they were going to do. The details of this proposal they wanted to master and to have outlined, and that becomes enormously complicated very quickly.

Young

Instead of starting—

Kennedy

They could have started any way. There were a lot of different ways you could have started. You could have said, “These details we’re going to leave to a board; these details we’re going to leave to different agencies to make descriptions”—which are suggestions now that are out there, in Tom Daschle’s book, and other kinds of things. They wanted to spell it out in detail, what they were going to do. That’s the way they thought was the best way to go, so that’s the way that they went.

I can’t give you what went on with the President in terms of why he made that kind of judgment rather than something else. I can’t give you that part. It was just that they were going to have the comprehensive universal, and they were going to develop their own proposal, and they were going to hear the people who were very good on it, which they did, and they were going to have that kind of a proposal. I think everybody understands now that that was a catastrophic mistake.

Young

Yes. Was there any consultation about this strategy with people in the Congress?

Kennedy

No.

Young

They just went ahead and did it?

Kennedy

They thought that they could get it done in a timely way. They underestimated the complexity of it, and then they were faced with a variety of other kinds of issues that came up during this period of time, which diverted the focus and attention away from it.

Young

Dan Rostenkowski gave an oral history interview.

Kennedy

Yes.

Young

Not to me but to somebody else, and he relates a conversation about that with the President, before Hillary [Rodham Clinton] was appointed to do this. Dan’s version of that was, “I told the President he’s making a huge mistake; that he ought to approach this—I said, ‘First of all, you’re a politician. Think about what you can get through and start from there. Let’s get something and get the people involved in Congress, rather than turn it over to [what he referred to as] a bunch of academics.’” Was that the impression created in Congress?

Kennedy

I’m not sure people saw it quite that clearly at the time, but that’s obviously, in retrospect, clearly what happened. You know, there are different approaches and ways of dealing. Sometimes people just send up ideas and let the other—but sometimes if they do that, they lose control over where it goes, so they don’t like to do it.

They made the judgment decision to be more specific. They had very able, gifted, talented people, very knowledgeable, and they were going to get it and get it right, and get the best people to try and get that right and do it in a timely way. But the time slipped. It became disjointed, it became uncoordinated, and there were a number of other factors that interceded and became important, and moved and shifted the calendar back on it, and that caused an unraveling of the whole process. And as the process deteriorated, the groups that were focused in opposition became stronger and stronger, and their ability to influence became greater, and they had very considerable success.

We missed the opportunity, at a key time in this development, to move this whole process into what we would call the Budget Resolution, which would have permitted us to expedite the process, and you would have had the legislation in March instead of in October. Senator [Robert] Byrd refused to do it. It would have been massaging the budget process, certainly, to get it to have an inclusive kind of program, such a massive program, but its implications in terms of the budget are massive. We’re talking about a healthcare system now of $2 trillion, so its implications in terms of the budget are massive.

But we were unable to get that done, and once we were unable to get that done, which was a major setback, we had mistake after mistake. Although, I have to give it to Senator Clinton—She mastered the details of this, appeared before our committee and other committees, answered all the questions, and they were complicated and difficult questions. She understood it and she was an effective spokesperson for it.

Young

In mastering the substance. But what about the politics?

Kennedy

The politics was that Phil Gramm and the Republicans decided not to let anything pass. This could have been healthcare, it could have been education, it could have been the environment, it could have been tax policy. They recognized, you have a Democratic President, a Democratic House and Senate, and the best way to undermine that is to show they are ineffective, and what came tripping down the pathway was healthcare—I think it could have been anything else—and he said, “We’re not going to let this thing go through.”

They had people who had been interested in healthcare who were prepared to move ahead, and they blew the whistle—[Newton] Gingrich blew the whistle—and said, “We’re not going to pass anything on through,” and these lemmings just followed. The record is there on it. They had a unified front in opposition to it. There was a small group of Republicans that tried to work with a group of Democrats at the very end of it, but it wasn’t a serious kind of effort. Bob Kerrey was involved in it, but it wasn’t a serious effort.

They made a judgment decision in this process—this was about ’94—that they weren’t going to let it go through. They made a calculated political judgment on it, and they were right, and Democrats lost, big time, in House and Senate. They served their special interests in terms of the insurance companies, in terms of the drug companies, in terms of the health industry professionals. They got massive contributions from them. Those groups got set up and were very effective, and it just ended the whole effort with a whimper.

We had Travelgate, Whitewater, and then we had the divisions in the Senate between our committee and Moynihan, with Moynihan wanting to do welfare reform, which is what he’s always been interested in. Therefore, we had meetings in the White House where the President said, “I want to do healthcare,” and Moynihan said, “No, we’re going to do welfare, and we’re not going to do it.” He was completely uncooperative. And [Lawrence, Jr.] O’Donnell, who is still around now doing these television shows like West Wing, was the staffer, and just would undermine any of the efforts that our committee had in trying to move this whole process. Moynihan undermined the whole process in terms of moving toward it.

So everything was delayed, and it isn’t difficult to delay things in the Senate. It isn’t a master plan, it’s just a whole process about how this delay took place, and with that delay, the corresponding actions that took place from the other side just became so overwhelming and so powerful that they effectively sank it.

Clinton went down in terms of public opinion. The administration was divided as to what ought to come up next. With his popularity down, they thought, Well, we’ll move ahead with NAFTA [North American Free Trade Agreement], and that antagonized Labor, which was trying to be of some help to us, so they took a walk. And you have the other kinds of activities that he was involved in, as I said: Travelgate, Whitewater, and other issues that undermined him.

Young

And deficit reduction came.

Kennedy

The deficit reduction.

Young

It came ahead of the budget.

Kennedy

The whole budget debate, which took a lot of effort and energy from the administration. It was decided by a single vote in the early summer, and healthcare was off to the side.