Transcript

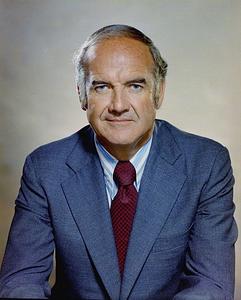

McGovern

I’m glad to be here. Ted Kennedy is one of my long, long-time friends. I regard him with special appreciation.

Knott

That’s nice to hear. We thank you very much, Senator McGovern, for being with us today. We’re very grateful to you for taking the time to travel all the way from South Dakota. Perhaps the best place to start would be to simply ask you about your first exposure to the Kennedy family. We know that you worked for President [John F.] Kennedy’s election in 1960 and then became Director of Food for Peace. Is that where it all starts for you?

McGovern

No, it began before that. I came to the U.S. House of Representatives in the ’56 election. I was there for four years. During that time, John Kennedy, as a United States Senator, was pushing the Labor Reform Bill, assisted by his brother Robert Kennedy. I co-sponsored that measure in the House of Representatives. I got to know both Bobby and Jack during that period rather well because there weren’t too many Democrats who were anxious to pick up that Labor Reform Bill. It offended some unions; others were perfectly happy with it. So I got to know them in that period. I guess it would have been primarily ’58 and ’59, after I had been reelected the first time.

Then in 1960, after my service in the House, I ran for the Senate in 1960 and was defeated by Karl Mundt, a hard-line, professional anti-Communist and not very well liked by John Kennedy or Robert Kennedy. They both came out to campaign for me in 1960, and I campaigned for John Kennedy all the way. I was advised by my staff not to do that. The big concern in South Dakota was that he was a Catholic, and we’re a strong Lutheran and Protestant state.

In that election—which he lost heavily in South Dakota, but nonetheless won the Presidency—I went down to defeat by less than 1% of the total vote. Jack called me right after the election. I couldn’t believe it. I was down in the dumps, because I’d given up a seat in the House—which would have been easy to retain—to run for the Senate, and I lost. He said,

George, I’m sorry.

He called me on the Thursday after the election, if you can believe that. He must have been exhausted, but he called and said,I’m sorry I cost you that election out there.

I saidJack, look, if I had won, I wouldn’t have given you credit. I’m not going to blame you for the loss.

He liked that answer, and he said,

No, Bobby told me what happened out there, and before you do anything, come to see me.

That lifted me right out of despondency to the mountaintop. And so I did, in a few days went in to see him. At first he thought about the Department of Agriculture, naming me Secretary of Agriculture, and then he said,What about Food for Peace? We’re going to start a new program at the White House and I want a full-time director, and you’ve been pressing this idea for as long as I’ve known you. What would you think of that?

I said,I think it would be great.

Well, from that time on, I came to know Bobby and Jack much better. My office was in the Executive Office of the President just across the street from the White House, and I got to know Ted. I met him at social functions and sometimes at functions at the Kennedy homes, but I really got to know him when I ran for the Senate again in ’62, this time against Francis Case, who died shortly after the campaign began. I ended up running against the Lieutenant Governor who was appointed to take his place.

So Ted and I came to the Senate the same day. That would have been in ’62 in his case because he was in a special election, as I recall, and I came at the traditional time, January of ’63. We were seated next to each other. It wasn’t planned that way, but we were in the back row, and we sat next to each other for the first two or three years. I don’t remember just how long. So I got to know him very well during that period.

Knott

You mentioned in your autobiography something to the effect that at first you weren’t sure perhaps what to expect, that he was the youngest brother, and perhaps your own expectations of him were a little low. Is that a fair comment?

McGovern

They weren’t as high as they were of Bob and Jack, who I thought were more experienced politically, more knowledgeable about the world in general and a little more sophisticated. I just wondered how Ted would do. On top of that, he was ten years younger than I was, and I was only 34. Well, that’s not quite right. I was 34 when I went to the House, but I was about ten years older than he was. I think he was elected to the Senate before he turned 30. When he was elected, he wasn’t eligible to serve in the Senate, but his birthday was between Election Day and swearing in in January.

Anyway, I quickly saw that he took that job seriously and that he was going to try to be an effective force in the Senate. He wasn’t very good at extemporaneous speech—to put it mildly—but he worked at the job. He tried to get briefed, and—like all the Kennedys—he had a first-rate staff. I think probably their dad pounded that into them, not to be afraid to have people working for you who know more than you do; it will help you. They all did that: Jack had Ted [Theodore] Sorensen, who was brilliant. Ted had the same head person as chief of staff, Carey Parker. The guy was just superb, and Ted knew that. He learned that rather quickly, and he still has him, I think.

Knott

Yes, he does.

McGovern

Carey Parker was an enormous benefit to him, as Ted would be the first one to say. So he got off on the right foot with a good staff and with a determination to be a good Senator. My opinion of him has risen steadily from that day to this.

Knott

You were on the Senate floor, I believe, when the word came that President Kennedy had been shot in Dallas.

McGovern

I was, yes. My recollection of that—it’s a long time ago—is that Ted was either presiding or was about to take over. Mike Mansfield motioned to me and asked if I would take the gavel—at least that’s the way I remember it. It was such a traumatic moment. I could be wrong on some of the details there, but I think that’s essentially it. And then Mike moved to adjourn the Senate.

Knott

Being his seatmate in those weeks and months after his brother’s death, do you recall how he seemed to cope?

McGovern

I asked him about that, how they withstood that death, and he said,

My mother had a lot to do with it,

her religious faith and her belief that Jack was still in God’s hands and that they would see the trauma, that accident or that tragedy, through. Later on, after things quieted down a bit, I asked him a few things about Jack, and he said,You know, George, I never really knew him very well. When I was growing up, he would come back up there to Hyannis Port on the weekends. He had a lot of back trouble, and frequently he would just to go bed, take a hot bath, soak in the tub and then go to bed and read. So I didn’t see much of him. I was much younger, and I can’t tell you as much as Bobby could or Eunice [Kennedy Shriver] or some of the others. I always admired him, but I frankly didn’t spend a lot of time with him while I was growing up.

Knott

I think there was 15 years between the two of them.

McGovern

That sounds about right.

Knott

You also were in a position to see both Robert Kennedy as a Senator and Edward Kennedy as a Senator. Could you compare and contrast the strengths and weaknesses of those two as United States Senators?

McGovern

Ted was the best Senator of the three, because he was more vitally interested in it than either Bob or Jack. I think Jack was thinking about the Presidency fairly soon after he got to the Senate. He had served in the House for a while. I don’t know very much about that part of his record because I wasn’t in Washington when he was in the House. But I think Ted is clearly the most productive and most sustained in the interests that he’s been pursuing. He was the best of the three in the Senate.

That doesn’t diminish my high regard for Bob and Jack. I thought President Kennedy was well on the way to becoming a strong and effective President. I think he’s one of the few who would have been even better in a second term. Bobby, after Jack died, became a different person, in my opinion. He was much more sensitive to the ills of the world. He was much more compassionate. He probably was the one with the strongest emotions of the three, and maybe with the greatest passion to change society, to change the world.

I think his great days came after the death of John Kennedy. He seemed to leave the role of the strong arm and the tough talk to protect Jack and became his own man. I thought those latter years, the last five years, were his best.

Ted has just seemed to me to grow steadily every year he’s been in the Senate. He loves the Senate, as near as I can determine, and I think that he gave up serious hope for the Presidency after Chappaquiddick. But I admired that that tragedy—which would have led most people to just say,

It’s all over

—I admire the way he really took hold of the Senate after that and worked just as hard, if not harder, than he ever had. He made that one brief stab at the Presidency that didn’t really go very far, but he’s a Senate man and he’s a Senator’s Senator, and he’s highly regarded on both sides of the aisle. I can’t say enough about Ted’s record as a Senator.Knott

Maybe we could talk a little bit about that.

Martin

First I wanted to ask how the more senior Senators responded to Edward Kennedy from the start. You would have been in a good vantage point to watch that.

McGovern

I think they were skeptical. They somehow thought that because Jack was in the White House and Bobby was Attorney General he rode the prestige of the family into the Senate, and they were reserving judgment on how well he would do. He did a very wise thing that I regret I never did. He went around and personally called on the senior Senators, I think beginning with Dick Russell. He likes to tell the story about how he reminded Senator Russell that he was the same age when he came to the Senate as Ted was, and Russell said,

Well, that’s true, but I had served as two terms as Governor of Georgia.

Ted broke into that hearty laugh of his. The senior Senator wasn’t about to say that they were on the same level when they got to the Senate. Anyway, that was a very wise thing to do. I think he went to both senior Republicans and senior Democrats and said that he was glad to be in the Senate and asked them for any advice they had. It broke down some of the skepticism.Martin

Were there any key points during those early first five or ten years when you think they started looking at him differently than in the beginning?

McGovern

I think so. Do you know when he was reelected the first time?

Knott

He runs in ’62 and wins that special election, and then he’s up again in ’64.

McGovern

I think after he won that election, I remember Senators walking over and congratulating him, both Republicans and Democrats, and he did that pretty much on his own. Jack was dead by then, and Bobby was heavily involved with the Department of Justice. I think it probably began to surface about that time. Also, a number of Senators noticed that he was well prepared in committee hearings. He always had good questions and stated his case pretty well. I heard, rather early on, comments about how effective he was in interrogating witnesses.

Martin

Maybe we should talk a little bit about—you only had the one committee overlap with Senator Kennedy, as far as we can tell.

McGovern

The Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs. His major interest was education and labor and issues of that kind. I’m trying to think what his committee was other than Labor. I believe it was the HEW [Health, Education and Welfare] Committee.

Knott

He’s still on the Judiciary Committee. I think even in this early period he was on the Judiciary Committee—

McGovern

Yes, I think you’re right.

Knott

—dealing with immigration.

McGovern

The other one was the one that dealt with the issues that came up in HEW on labor affairs. He did a good job on both of those committees. He was always well prepared. He was good at cross-examining witnesses. He began to inform himself pretty well on the central issues, and I think he enjoyed that work.

Martin

What role did he play in the Select Committee on Human Needs?

McGovern

That was a Select Committee, and he was heavily burdened already by the other committee. The Select Committee came into being about ’68. He attended the hearings, and he had good questions to ask. I don’t remember him really pushing hard in that committee. Jack [Jacob] Javits was the beginning ranking Republican. He was later replaced by Bob Dole, and each of them took a very active interest in that committee, and so did other Democrats, but I don’t remember that being one of the committees that Ted gave a lot of time and effort to. He knew it was a temporary committee and that if he was going to make his name, it had to be on these permanent standing committees.

I think Bob Dole and I made something of a name on the Select Committee because we carried the burden. We still work together on hunger issues. But I don’t remember that being one of Ted’s starring roles. It’s not a criticism. He tried to use his time where he thought he had the biggest chances of accomplishing things he was interested in.

Germany

I wanted to pick up on looking back at Ted Kennedy’s early Senate career when you were seated with him. In the ways that you could see, what was his relationship with the White House, in particular Lyndon Johnson?

McGovern

I think he had pretty good relations with Lyndon Johnson. He avoided criticizing him, and even on the war, his criticism was never personal. It was on other aspects of the problem rather than Presidential leadership. I think Ted always had pretty good relations with Johnson, and I think he enjoyed Johnson’s raucous humor and his sometimes barnyard language. I remember Ted talking to me about some of the things Johnson said in private, and he could hardly tell the stories without laughing. So I think he enjoyed Johnson.

Knott

You came to the Senate at a time when the institution was beginning to change. There were a lot of northern liberals, for lack of a better term, like yourself, who came in in the ’60s, and you were facing these old southern barons. Could you tell us a little bit about that? Is it true that the institution began to change or—?

McGovern

Well, that was certainly a much more liberal Senate than we have today. And I do think the infusion of a number of new Senators—eight of us came in in ’62: Abe [Abraham] Ribicoff, Gaylord Nelson, Birch Bayh, John Culver (who incidentally was Teddy’s administrative assistant for a while), Danny Inouye, Alan Cranston. There was quite an infusion of liberal-minded, what I call

New Deal Democrats,

who came in at that time, and I think it did bring new life and force to the Senate and made possible the great civil rights victories in ’64 and ’65. It helped produce the strong anti-war movement that developed around the Vietnam issue that the more traditional Senators did not pick up on, with the exception of [William] Fulbright and Mansfield and [George] Aiken and a few others like that.So it was a good time to be in the Senate, from my point of view, and we tended to take on issues that weren’t in our committee jurisdiction—at least I did, and I think a lot of others did as well. I went after our Cuban policy (or lack thereof) even while John Kennedy was still in the White House. I gave my maiden speech,

Our [Fidel] Castro Fixation v. the Alliance for Progress.

A number of people picked up on issues like that that ordinarily more respectful, traditional Senators would reserve to people who had committee assignments in those areas.Knott

Almost as a side note, when did your own position on the Vietnam War begin to change? I’m correct in assuming that it did change at a certain point?

McGovern

Well, it deepened. I came to the Senate thinking that we should not interfere with those revolutions in Asia. I had that feeling when I was a graduate student at Northwestern back in the ’40s after World War II. I had read [Owen] Lattimore’s book, The Situation in Asia, which opens with the lines,

Asia is out of control; revolutions are taking place to throw off the imperial bonds and social revolution is exploding.

So I came there thinking—mostly intellectually, not with my gut—that we were making a mistake in mucking around in Southeast Asia. I didn’t say much at first. My first dissenting speech was the one on our Cuban policy. But by the fall of 1963, I made a speech saying that the troubles we’ve fallen into in Vietnam will haunt us in every corner of the world if we don’t realize the revolutionary forces moving there—forces that couldn’t be contained by military intervention. Then John Kennedy was assassinated, and I dropped the criticism of the White House on any score.

I went out and campaigned for Johnson and [Hubert] Humphrey in ’64, as did most of my class. We believed Johnson when he said that two American destroyers suffered an unprovoked attack. And then later we learned, after the vote, some months afterwards, that there was probably no attack ever launched, and if it had been, it wouldn’t have been unprovoked because those destroyers weren’t just sightseeing up there on the coast of North Vietnam.

So after that, and after the ’64 election, I was ready to go again. And sure enough, after saying we weren’t going to take over a war that had to be fought by Asian boys, they started to escalate the war in January and February of ’65. I really opened up then until we finally got out ten years later.

Knott

Did Johnson try to give you the treatment?

McGovern

Oh yes, he sure did.

Knott

What was that like? Unpleasant?

McGovern

It was unpleasant because I liked him as an individual and because I knew that he was struggling with that issue,

LBJ, how many kids have you killed today?

and all those chants, and so on. I knew that it was tearing him up. I didn’t know then that he himself thought the war was a disaster, as the Johnson tapes later revealed—both he and Dick Russell were concerned. You know that better than I; you read those tapes. They both thought the whole thing was a disaster, but once he started down that course—which he thought was continuing John Kennedy’s course, the same Secretary of State, the same Defense Secretary, the same National Security Advisors—he was just unwilling to say it was a mistake and we’re going to get out.So when you’d go to the White House and plead with him to change course, he’d say,

Now, George, look, I had Joe Rauh and the liberal batch in here yesterday, and they’re saying, ‘Just pull out.’ You know I can’t do that. Then I have [Curtis] LeMay and his crowd in here saying. ‘Bomb the hell out of them,’ and I’m not going to do that.

He saw himself as walking right down the middle of the road and fending off these hysterical people on both the right and the left. And it really pained him that his old friends in the Senate—Fulbright and Mansfield and George Aiken, and then the younger crowd, Frank Church and eventually Bob Kennedy and Ted Kennedy and I and others—had deserted him on this. And I think he just dug in all the harder.

Germany

How frequently did you speak with Johnson?

McGovern

I had just one one-on-one conversation with him. I asked for an appointment, and to my surprise, it came through within a couple of hours. I went down there about 7:00 one night. Bill Moyers set up the appointment. I didn’t leave angry; I left almost in tears. I felt so sorry for a President who was just so tragically misled on what was going on over there.

I had the same experience with Hubert Humphrey, my next-door neighbor in Washington. They just couldn’t see the folly of that intervention. So my success in changing minds at the White House was nil.

Germany

How confident were you of the information you were receiving about Vietnam?

McGovern

Pretty confident. I went to Vietnam three times during the war. I had a son in-law who was fighting with the Third Marines, and I thought a lot of him. I went over there for Thanksgiving in 1965, and I saw the situation with my own eyes. I went to the hospital in Saigon where a lot of the American troops were and saw guys with no feet and no arms, no faces some of them, no genitals, and I saw what was happening to the Vietnamese civilians, too. I went to a hospital up in Da Nang, and there must have been—I don’t know, if you could squeeze 2,000 people into a hospital using the verandas and the lawn, all covered with these little iron cots. They were shot up by our artillery fire and bombings. I came back from that trip just determined to do everything I could to put an end to the war, and I never changed after that. I always regretted I voted for the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, and so did practically everybody else. We were misled.

Germany

Were you aware of the sabotage engagement that was going on, or was that something that was more secret?

McGovern

In Vietnam?

Germany

Just before the Gulf of Tonkin.

McGovern

I knew something. Was that the Phoenix Program?

Germany

The OPLAN 34A.

McGovern

Oh, yes. I didn’t know much about that at the time. I think Wayne Morse and Ernest Gruening used to trade notes all the time and had a former senior staff member in the Pentagon who was confidentially feeding them information that I later learned about from Ernest Gruening. They got their guard up on the Gulf of Tonkin thing, but this guy swore them to secrecy on it, and they respected that. They never revealed who he was, even to other Senators, but it was a senior official in the Pentagon. But I didn’t know a lot of those details.

By then, though, I thought if we were going to enter in Vietnam, we entered on the wrong side. If I had been a young guy growing up in Vietnam, I would have been a follower of Ho Chi Minh, and I knew that, just as I would have been a follower or Fidel Castro up in the mountains against [Fulgencio] Batista. Not that I like Communism—I’d hate to have to live under a system like that. But I thought they had grassroots support in both cases. I never once said in the Senate or publicly that I thought we entered on the wrong side. I pled for no intervention. But if we were going to intervene, we entered on the wrong side. First of all, they were the losing side, and secondly, I thought they were more corrupt than the rebels.

Knott

Did you ever consider voting against the Gulf of Tonkin resolution? That was a tough vote for you.

McGovern

Oh yes, I considered it. Gaylord Nelson, who came to the Senate the same day I did and who was my other seatmate in the Senate, drafted an amendment that said,

Nothing in this resolution carries the implication of a deeper military involvement.

And I said,Put me on as a co-sponsor. I think that’s a good idea. That will at least protect us somewhat.

We both considered just voting no.So we took that to Fulbright, who was managing the bill, in whom we had a lot of confidence. He said,

Well look, guys, this thing doesn’t mean a damn thing. Lyndon wants it. [Barry] Goldwater is yapping at his heels, and he wants this thing to get the Senate on record. Let’s give it to him. If you throw in that amendment, then we have to go to conference with the House

that had already passed it. He said,That will tie it up and tie up the other amendments. Let’s give Lyndon what he wants. I wouldn’t vote for the damn thing if I thought it would change our policy one iota. They all know we’re against it, and I don’t see anything in this that commits us to anything. Lyndon hit those boats out there, and let’s let it go at that.

And so we never offered the amendment.

There was another Senator who got up and questioned it, not [Charles] Mathias, the other Senator from Maryland, a Democrat: [Daniel] Brewster. He got up and said that he had read that this thing was being exaggerated, and he asked Fulbright some questions. Fulbright gave him the same assurance: that it didn’t really have any meaning at all and was more of a symbolic gesture—and in a sense that’s right. It was more of a political ploy than anything else, because we were already at war. It wasn’t the Gulf of Tonkin that committed us to the war in Vietnam. Some of us had already made speeches against the war when we voted for the Gulf of Tonkin.

Knott

Did Robert Kennedy or Edward Kennedy talk to you in private about their feelings about the Vietnam War, in particular the fact that their brother, President Kennedy, had played some role in escalating the American involvement?

McGovern

As long as he was in the White House, I never heard a whisper from either Ted or Bob, which is understandable. I know George Bush, Sr. is against the war in Iraq and was before we went in, but he’s not going to pound the pavement condemning it now. He certainly was against it before we went in there. I think, in just listening around the cloakroom, that Ted and Bob both had reservations about the war. I think John Kennedy did too, but my view after Jack Kennedy was killed was, Let’s wait until after ’64 and get that election out of the road, and then we can express ourselves more fully. I thought, Here’s Lyndon taking over, and I’m not going to be pounding him when he’s running for reelection in ’64. Better to have Johnson than Goldwater. So I laid off for a few months.

Knott

Are you of the school of thought that believes that had President Kennedy lived, the whole course of the war would have been very different?

McGovern

I think it would have, but I’ll be darned if you can find much proof of that. So I always tell audiences when I’m asked that I don’t know what he would have done, but I do think he was more personally self-confident than Johnson. Johnson always thought these smart guys from Harvard and Yale and Michigan State were pushing the war. General [Maxwell] Taylor and other people like that—this brain trust that Kennedy had assembled—they knew more than he did. And so he tried to keep as many of them on as would stay.

Jack made a speech in September before he died and said,

In the final analysis it’s their war. They’re the ones who will win or lose it. We can send our men out there, we can send advisors, but only Vietnam can resolve this conflict.

That was an indication, I thought, that he might put the brakes on if he had been reelected and try to see if something could be worked out to justify our disengagement. That’s about the only concrete thing.Others on the inside who knew him better than I did at that stage of his life may have heard doubts and fears about it. I don’t know. We now know that [Robert] McNamara had questions about it. But I guess my answer is I don’t know what he would have done. I think, knowing him, that he would never have authorized 550,000 troops over there. If he had seen that every time the Army asked him for more troops, he granted it and we were getting nowhere, I think that he would have had more confidence in his own judgment and would have balked at some point. And he might even have balked on the bombing of North Vietnam after the My Lai massacre, things like that. By then, you know, Bob and Ted were dissenting from the war. Whether they would have if Jack were in the White House, I don’t know. What do you think? It’s hard to know, isn’t it?

Knott

Kent’s the expert on this.

McGovern

What do you think, Kent?

Germany

It’s complicated.

McGovern

Yes, it is, it’s very complicated.

Germany

There are a few recordings where Kennedy is talking to McNamara about a possible plan that the Pentagon had for withdrawal. It seems that it was all dependent upon things going well on the ground; then you could withdraw. But until then it would be very difficult, and they would just come up with a new date.

McGovern

It seems to me if Jack had gotten reelected in ’64 and Mansfield, Fulbright, Aiken, John Sherman Cooper—and maybe his brothers—asked for an appointment and went in to say,

Look, you just have to wind this up. We’re getting nowhere,

I think he would have been more confident about taking that case to the country. He wouldn’t be running again. Jack Kennedy always had a lot of self-confidence, and he didn’t have some of the anxieties about his own background and his own knowledge that Lyndon had. Furthermore, people like Ted Sorensen and Arthur Schlesinger and others would have been weighing in, I think, with the same message. So I guess I think he would have probably called a halt at some point. I have no way of knowing that, of course.Martin

I wanted to bring us back to the Senate for just a moment and ask your impression of what led to Senator Kennedy being elected majority whip in 1968 or ’69. Then he winds up losing to Robert Byrd in 1971.

McGovern

He was running against Russell Long, and Russell had some problems. I’m not going to go into that too much, because Ted had a few himself. I think a lot of the Senators who knew Russell well and who liked him also thought that he had some personal difficulties that might make it hard for him to bear up under the pressure of the majority leader’s post. He would sometimes come to the Senate pretty inebriated.

Ted was younger, maybe a stronger person, and I think he was better liked by the liberals in the Senate. Russell was a good populist like his dad. He’d soak the fat boys and that kind of thing. He was a genuine populist, but I think the liberal-to-moderate members of the Senate were just a little bit more comfortable with Ted. He participated in the civil rights revolution, helped carry the day on the Senate floor. He was for helping working people. He was a strong advocate of fairness to people who were poor and didn’t have the advantages. He was always a champion for healthcare.

Ted carried that ball almost alone in the Senate for quite a while, and so I think the people who voted for him for majority leader did represent a majority opinion on the central issues at that stage. That plus some personal questions about Russell, I think, explained his upsetting a person with considerably more seniority. As to why Bob Byrd prevailed, I’ve forgotten what year that was.

Germany

Nineteen seventy-one.

McGovern

Seventy-one. We’d had Chappaquiddick. Bob Byrd was a tireless worker for that job. He buttonholed everybody in the Senate, not once but a half dozen times. He just outworked Ted. He wanted it more, I think.

Martin

Did he talk to you about getting the vote?

McGovern

Oh yes, he sure did. I had told him I was committed to Ted so I couldn’t support him, but I said,

I think you’ve been a conscientious Senator.

Little did I know he was going to emerge as the strongest opponent of the Iraqi disaster. I didn’t know that he was going to emerge as one of the great champions of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Even if I had, I was committed to Ted. How could I not vote for him? He and I had been seatmates and friends and shared many a legislative battle together. So I just told Senator Byrd,I’m sorry.

I wished him well, but I couldn’t support him. I think a number of other people did the same. He talked to everybody, as far as I know.Martin

Do you remember what his argument was for why he should be?

McGovern

He just kept stressing he’d always have an open door, he’d never be too busy to see any Senator, that he knew the special problems every member of that Senate had in their home state, and that he would be sympathetic to that and do all in his power. He was a senior member of the Appropriations Committee, and he said how helpful he could be on things that were important to South Dakota, that he was a poor guy who had worked his way up—got his college degree and his law degree after he went to the Senate—and he knew the problems of working people and poor people, coal miners and all these things. He made a very good case for himself, and I think he was a good majority leader. He once told me that if he had still been majority leader, Clarence Thomas would have never gotten on the Supreme Court, and I happen to think that’s true.

Martin

When Kennedy gets elected to majority whip, how did that group of young liberal Senators respond? Did you see this as a landmark shift in the Senate at the time?

McGovern

Yes, I thought it was. I thought it was an important shift. I think Ted was backed by Mansfield, who had great prestige in the Senate. I can’t speak for all my colleagues, but I think that was the general impression, that this was a big victory for the liberals in the Senate.

Martin

And then when Byrd wins, is it seen as a backsliding?

McGovern

A little, yes, more of the Old Guard taking command again. But Byrd turned out to be better than we expected; I think even Ted was somewhat surprised. Ted always treated Byrd with respect and tried to work with him when he could.

Martin

Some people have said that losing to Byrd was one of the best things that happened to him as a Senator because he focused his energies on committee work.

McGovern

I think that’s true. I think it was one of the better things that happened to Ted because the office of majority leader takes an enormous amount of time, and Ted would have been easily accessible to all of us. He would have given a lot of time to that job.

As it is, I honestly believe that Ted is the most productive Senator of the last half century. I wouldn’t go back to George Norris and Bob LaFollette and some of the great figures of an earlier time, but at least in the nearly 50 years I’ve been in Washington—I’m not there now, but I’d been there about 50 years—I think he has emerged as the most productive member of the Senate of either party.

Hubert Humphrey was very creative and active when he was there, and I don’t want to take anything away from him. Lyndon Johnson was effective in getting things through the Senate, but more after he became President than before. So as a Senator, I’d rate Ted number one over the last half century just in terms of what a Senator is supposed to do, representing his state, being well informed and active on the great national and international issues. I can’t think of anybody who has a more impressive record than he does. And frankly, that’s a big surprise to me. I wouldn’t have said that when I knew him the year of his arrival. But as I’ve said before here today, he got better every year he was there.

Martin

How did he overcome Chappaquiddick inside the Senate?

McGovern

That was tough. I don’t know how he overcame it in himself. Most of the Senators I know would have just resigned, would just think, Oh, hell, I’ve screwed this thing up, and I’m going to get out of there. He never did. He was at his office early and late, I think, from the day after that tragedy. Obviously it tore him up inside, but he never quit. And while he mishandled it at the time—as he and everybody else knows—he never let it get him down. It never slowed his work in the Senate that I could see, and I knew him pretty well.

I think he just decided I’m not going to let this one tragic incident—I can’t bring this girl back. I can’t erase what’s done. I’m going to continue to be a good Senator. And he pulled it off. It took, I think, more personal and inner strength and integrity than I thought was possible. And he did it. So I think Senators who at first were shocked by the incident and by the way he handled it gradually came around to the view, Here’s a strong man who’s handled this well. I’m trying to think of the date of Chappaquiddick.

Knott

It was the day of the moon landing. It was July 20, 1969.

McGovern

That’s what I thought. I remember now. I was in the Virgin Islands when it happened. I was thinking about running for the nomination then, because I didn’t think Ted would after the death of both Bob and Jack. But when I heard what happened, I fell asleep after a while. I was at a big party at Henry Kimelman’s home in the Virgin Islands. It was a beautiful night, and I was sitting out there on a beach chair. And one by one everybody else left the party and went home.

I fell asleep in that chair. I woke up the next morning with the sun shining in my face, and while I don’t believe too much in hunches, I woke up and thought, You know, I’m going to be the Democratic nominee for President because Ted won’t run now for sure. And it turned out to be right. I had a strong feeling that day. It wasn’t a joyful feeling; it was just kind of a strong hunch that I was going to make it all the way to the nomination. It shows you how wrong I could be. I thought winning the nomination was the big hurdle, that anybody could beat [Richard M.] Nixon. So that shows I can be as wrong as the next person about political judgments.

Knott

Can I take you back to 1968 just before we move on? You were approached by Allard Lowenstein and others in this group that was attempting to put forward an anti-war candidate. Senator [Eugene] McCarthy eventually jumps in and then ultimately Senator Robert Kennedy gets into the race. Could you talk a little bit about your own decision in that matter, and also further on, whether you recall any conversations with Edward Kennedy about any of these matters?

McGovern

As early as the summer of ’66 I was out at Robert Kennedy’s home, and I urged him to run for President. I argued that he was the best-known and most prestigious person, and if for no other reason, he had done a good job as Attorney General as the brother of the President, and that I thought somebody ought to raise the banner against continuing that war. And I thought it ought to occur inside the Democratic Party, where most of the debate was taking place anyway. Most Republicans kind of finessed the issue, saying that they were going to follow the Commander in Chief, and they said that whether it was Lyndon or Richard Nixon.

But inside the party was this raging argument, and I urged Bob to run. He didn’t say he wouldn’t; he said,

You know, George, if I jump in, that’s going to convince everybody I’m the ruthless son of a bitch that a lot of people think I am. I just can’t do it.

But I kept after him, and finally one day down in the Senate gym, Teddy said to me,

You know, George, I don’t think you ought to keep urging Bobby to run unless there are a lot of other people willing to speak up and go out and campaign for him. If you’re really serious about this, there has to be some kind of organization, some indication that a lot of other people would speak up on his behalf.

It was about a year later that Marcus Raskin and Dick Barnet and Al Lowenstein and other young people came to me to run. They didn’t think Bobby was going to do it. And I wasn’t sure he was, because he never really said,

I’m giving it serious thought.

They didn’t think that I or Bobby or anybody else had a chance of winning the nomination. They didn’t know that Johnson was going to pull out of the race. But the idea was that somebody ought to raise the banner, and if they could get 20% of the vote—or 30% or 40%, whatever—it might frighten Johnson into changing the policy.I said,

Well, if that’s what you want to accomplish, why don’t you get some guy who’s not running for reelection to the Senate? I have a tough race out in South Dakota. I came here with a recount and only a 597-vote margin.

And they said,Well, who would you recommend?

So we got out the Congressional Directory to see who was running in ’68, and I noticed that Lee Metcalf of Montana and Gene McCarthy were not running in ’68. I said,

Why don’t you go see one of those guys?

They went to see Metcalf first, and he practically threw them out of his office. He said,I don’t want to run for President. I don’t want it if you give it to me. I don’t want the damn job. I’m going to be a United States Senator from Montana as long as they’ll have me.

Then they went down to see Gene. I didn’t know Gene was even thinking about it, but I suggested they go down to see him. An hour later, Gene sauntered onto the Senate floor and made a beeline for me. He said,

Well, your guys came up to see me about the Presidency, and I think I’m going to do it.

I could have fallen over. I had no idea he was even thinking about it, but you don’t make a decision like that as a snap judgment. Immediately I saw Bob out in the Senate cloakroom and said,

Bob, I have to tell you that Gene is going to run for the nomination.

He said,You’re kidding!

I said,No, he’s going to announce.

And he immediately said,Don’t make any commitments. Don’t do anything until we’ve had a chance to think about this.

And I knew what he was thinking: Why didn’t I do this? If somebody else is going to do it, why shouldn’t I have?Then I saw Ted again, and he said,

Now don’t try to push Bobby into this thing.

I think he was thinking, We don’t need another dead Kennedy, and he won’t win anyway. Then he stressed again,Unless there’s some kind of uprising out there of people who are going to support him—we don’t want him out there all alone.

So I eased off a little.A couple of days later, Bobby asked me if he could see me. I said,

I had lunch today with Frank Thompson of New Jersey and Lee Metcalf, Gene McCarthy, and Stewart Udall.

We had a little group of five who met every Friday at noon, and that’s what we were talking about, the Presidency. He said,Do you mind if I come over?

I said,No, they’re still here.

So he came over and stayed a full two hours with those other Congressmen and me. We were divided on whether he should do it. We all thought he shouldn’t jump into New Hampshire since it was coming up in just a few days and it might blur the distinctions if he took a lot of votes away from Gene. We weren’t even sure he should enter Wisconsin, which was also just a week or so away. But he jumped in.

He went home that night and had another meeting with some of his staff and others and decided to go. I don’t think Ted was overjoyed. You could ask him about that, but I think he had serious reservations about it. That’s my impression from what he said to me. I think he was afraid of it, afraid of the security, afraid of whether he’d look ridiculous, whether he would alienate the power players in the party in labor and elsewhere. I don’t know, but I think he had serious doubts about it, from what he told me.

Knott

Then you went on to campaign with Bobby in South Dakota—if not elsewhere.

McGovern

Yes. I never really endorsed him officially, but I gave him an introduction that led his fellow, [William] vanden Heuvel, to tell the National Press Corps,

If that wasn’t an endorsement, we’ll take that any time.

That’s the way Ethel [Kennedy] took it. She called me up the next day and said she’d never forget that introduction. So the word spread—it was a virtual endorsement—but I had said I wasn’t going to get into it because Hubert was my next-door neighbor. But I was for Bob because of the war.Knott

Do you recall the period around the time of the convention after Robert Kennedy was killed, where there was an attempt to enlist either Senator Kennedy or perhaps yourself to pick up the anti-war banner?

McGovern

Mayor [Richard] Daley and others were pressing Ted, but Bobby’s staff were pressing me to do it. Joe Dolan, his speechwriters, [Adam] Walinsky and [Peter] Edelman and Frank Mankiewicz, John Douglas, Fred Dutton—a whole series—were urging me to run. They didn’t think that Teddy, as they put it,

was quite ready for it at this stage.

And I think they also had fears about another assassination attempt.So they really camped out on my doorstep. I accepted an invitation to represent the Senate at the World Council of Churches in Uppsala, Sweden—John Brademas was invited from the House—because I just wanted to get away from it, get out of the country for a week or ten days. I landed in London coming back, and here’s the CBS crew,

Are you going to run?

And then I get back to the Senate, and these guys are over there still talking to me about it. I finally decided to do it even though I was right in the middle of a hard race for the Senate. I jumped in and did the best I could.It was only 18 days until the Democratic Convention. All the delegates had been picked. So I was really just raising the banner again, and I got all of Bobby’s delegates. They all came over, 143 delegates. I’ve always been glad I did that. I think it had something to do with me winning the nomination four years later.

Knott

Why don’t we jump forward, then, to that?

Martin

I wanted to touch on the development of the peace plank. Could you talk us through how those negotiations came about, the degree to which Edward Kennedy was involved?

McGovern

I don’t think Ted was at the convention, but Clark Kerr, the president of the University of California, and Walter Reuther got together on a compromise plank, and they ran it by Gene McCarthy and he accepted it. They ran it by me and I accepted it, and they ran it by Hubert and he accepted it. So they had all three of the announced candidates saying it was fine.

Then they took it up with Johnson: no. He virtually told Hubert,

If you run on that plank, it will be without my help. You know, I’ve talked to Richard Nixon, and he’s agreed not to raise the Vietnam issue in any significant way except to say that he has his own ideas how to settle it. If you come out for anything other than that, I’m going to have to oppose you.

Hubert then had to reject it, and I think that cost him the election, the fact that he wouldn’t separate himself from Johnson. He did once, in Salt Lake City. He had spoken in Sioux Falls the night before and asked me how I thought it was going.

I said,

Hubert, you can’t sell this war any more. People think of you as the peace man. You’re the author of the Peace Corps. You’re the author of the Arms Control Agency, and a great champion of civil rights. You just can’t carry this war. You have to do something.

He made the speech in Salt Lake City the next day. But then Johnson raised hell with him again, and he backed away from anything that looked like dissent on the war. I think it cost him the election. It’s too bad, too, because that’s when we should have gotten Nixon. He’d been out of office for eight years. He had lost to Kennedy in ’60 and then lost to Pat [Edmund G.] Brown in the Governor’s race. And Hubert at that time was Vice President of the United States. He was the incumbent.

Nixon, as I say, had been out of office for eight years, and we had George Wallace running as a third-party candidate. He got ten million votes, which had to be right off the top of Nixon’s votes. I’ve always thought if Wallace had not been shot just before the convention of ’72 and had run as an Independent—which he had every intention of doing—he’d have gotten twenty million votes. Under those conditions in a three-way race, we might have won that election. I don’t know what role Ted played in that peace plank. I’m sure he approved it, if he was asked.

Martin

It’s sometimes referred to as the McCarthy-McGovern or McGovern-McCarthy peace plank, and sometimes Kennedy’s name gets hyphenated in there.

McGovern

Does it? He may have had something to do with it. I don’t know. The impression I got from Clark Kerr and Walter Reuther was that it was up to Hubert and Gene. But they may have talked to Ted. I, frankly, didn’t know the pressures that were being made on Ted to enter the race. I knew that Mayor Daley would like to see it, but I didn’t know about that movement until afterwards. And I didn’t know it was still going on after I went to the convention with Bobby’s delegates. I probably would have yielded to Ted if I had known that he was giving any thought to it. But he told me that he wasn’t going to run, or I would have probably never gotten into the race at all.

Knott

You mentioned your—I’ll use the term epiphany—on the beach in the Virgin Islands. Did you go to see Senator Kennedy at some point and talk to him about 1972, about your intentions, about his intentions?

McGovern

I really didn’t. I just thought this was something I had to decide and had to do, and I wasn’t running for reelection that year. I thought I had done well in the few days I was in in ’68. There was one televised debate with Hubert and Gene and me in Chicago. It was sponsored by the California delegation, but it was carried on all the networks. If I do say so, I came out on top in that debate by, I think, a widespread consensus.

And then I was reelected by a sizeable margin in South Dakota, and I headed up that Democratic reform committee, called the McGovern Commission, and that went very well. It was controversial, of course, but I thought I stood up pretty well under the conflicting forces there. I just decided that I should do it, so I went into that race without really serious consultation with Ted until after I had made my announcement.

I probably should have gone to see him. I think Ted would have said,

I’m not going to do that,

but I should have shown him the courtesy of going to see him. I don’t quite know why I didn’t. I guess I just had a determination to want to do it, and I always thought that if I got nominated, I would ask Ted to be my running mate. I thought for a Kennedy to take second place on the ticket might erase the final images of Chappaquiddick, the people would say,He’s done his penance now to take second place to a junior Senator from South Dakota with three electoral votes.

That was in the back of my head, my plan to ask Ted to run with me. And then, win or lose, he would be the nominee the next time. But I never talked to him about it, and I regret that.Martin

Can I ask why you thought you should have talked to him ahead of time?

McGovern

I just think it would have been the courteous thing to do. For years Democrats had thought, Well, he’s the third Kennedy on the scene, and he’ll be our standard bearer sooner or later, and I just thought that, as a courtesy, I should have gone to see him.

Another reason—one of the things that brought that home to me—is that he called me in Chicago in 1968 when I was heading up the Robert Kennedy slate, and he said,

George, I just want to tell you, I know there are some rumors out there I’m thinking about coming in. I’m not going to run. I think you’ve done a good job; stay in there.

The fact that he did that made me think, Why didn’t I do that to him when I decided to run in ’72?Martin

Before we move too much farther along, I want to go back and ask about the McGovern-[Donald] Fraser Commission. To what degree was Edward Kennedy involved or consulted?

McGovern

I don’t think very much, to my knowledge. You know that commission was mandated by the ’68 convention. I think the Humphrey people were in the lead on that because they wanted to pull the party back together, and they thought that would be one concession they could make to Gene and the McGovern people. I never did push that reform commission. I think to this day a lot of people think I engineered that in order to strengthen my hand, but I never told anybody I thought we needed to set up a reform commission. That was out of my hands but was overwhelmingly voted in by the convention of ’68, which were mostly Humphrey delegates.

The Kennedy and McGovern and McCarthy people went along with it, but Hubert was the one who talked me into becoming chairman. I frankly didn’t want the job because I knew it was going to be a political can of worms for whoever took it. You couldn’t possibly please everybody. But once I took it, I was determined to see it through. Hubert was then the titular head of the party, and he said,

George, I think you have to do this because you’re acceptable to the Kennedy-McCarthy wing of the party

—as it was called—and you’re acceptable to the party regulars. You endorsed me right after I won the nomination in ’68. You campaigned for me in ’68, and you’re acceptable to my people. I’ve checked it out with them, and I wish you would take it.

So I did, and I think we did a good job with those reforms. They’re still on the books, with only one substantial revision—which is one that I supported after it was offered. That was before the ’84 campaign. There was a growing consensus that if were going to get a candidate who could win in the fall, it had to be somebody who had the stamp of approval of the party establishment: Congressmen, Senators, Governors, national committeemen and women.

A motion was offered to modify the McGovern-Fraser rule so that roughly a fourth of the delegates every time would be members of Congress, Governors, members of the Democratic National Committee. And to everybody’s surprise, I supported that when it was offered because I thought it did make a certain amount of sense that people who work at politics every day of their lives should have a little more concessions than the people who were there for one election and maybe never heard from again. So I supported it, and I think it was a good compromise. But now, those much-condemned reforms are still on the books, and the Republicans have adopted most of them. So it must be acceptable now.

Martin

When you were making or suggesting some of the changes, did candidacies such as Edward Kennedy’s future bids for the Presidency come up?

McGovern

I don’t think so. Fred Dutton, who was on the commission, insisted that while we could come out against winner-take-all rules, we couldn’t do it for California, which had operated under that system for a long time. They had to have one more roll of the reel before they had to give up winner-take-all. Everybody understood that it was a special concession to California. Ted was an eloquent advocate of it. I thought it was a little inconsistent for us to recommend an end to winner-take-all rules and then make an exception for California, but that got unanimous support on the committee, and all the prospective candidates in ’72 understood.

But once I won the nomination, it didn’t stop all the other candidates from getting together and leading a fight at the convention to bar the winner-take-all rule in California. That was devastating for us, because instead of having a month after we won the nomination—let me just give you one illustration. It’s kind of irrelevant to this interview on Teddy, but Hubert was asked on CBS—I think it was on the Sunday program—

How do you expect to overtake George McGovern in this race? After all, he’s won primaries all over the country.

He said,

Everything? He hasn’t yet won California; that’s the big one. That’s where the winner takes all the delegates.

This is Walter Cronkite interrogating him on the network a week before the California primary. So he understood the rule. But he and his staff led the fight, once I won California, to take it away from us on the grounds that the winner-take-all rule was in violation of the new party reforms.If we had a chance to defeat Nixon, I think it went out the window the day they introduced that resolution at the convention, because we had introduced it to the press before the convention. I worked my tail off for the next 30 days, calling every delegate all over the country. So did Frank Mankiewicz and Gary Hart and Rick [Richard] Stearns. We just worked our tails off night and day to save that California delegation, without which we wouldn’t have won the nomination, in all probability.

That month before the convention is when we should have been deciding on a Vice Presidential running mate. We should have been figuring out the plan to defeat Nixon, whom we hadn’t given a thought to up until then because we were involved in this knock-down, drag-out for the nomination. A lot of mistakes we made out of the sheer fatigue of that convention. So I’m not sure that anybody could have defeated Nixon in ’72, but if we had a chance, it went out the window with the California challenge and all the resulting complications after that.

Although, what turned it into a landslide was the shooting of Wallace. You talk to any of the Nixon people, and they’ll tell you that. Richard Nixon would tell you that if he were still here. Once Wallace was shot—you remember after he won in ’68 over Hubert, the first thing he did was to fill his staff with public relations executives—[John] Ehrlichman, [Harry Robbins] Haldeman and half a dozen others.

Usually you had lawyers as special assistants, people like Ted Sorensen and Myer Feldman and so on. He loaded the White House with PR experts, and they launched the southern strategy. They made no bones about it. They called it the

southern strategy,

which was to recapture that Wallace vote they had lost and that almost elected Hubert in ’68.Hubert came within 500,000 votes, the same majority that Al Gore got against [George W.] Bush in 2000. When Wallace was shot a month before the convention, you had that Wallace vote just swinging over to Nixon. It was the Wallace vote plus Nixon against a junior Senator from South Dakota, and from that point on, it was no contest.

I hope that doesn’t sound too defensive. I wasn’t shocked that I lost. I was shocked that I carried one state, and I think that landslide was the Wallace merger with Nixon, which he had been courting carefully for four years. I went to George Wallace and asked him if he would endorse me after I won the nomination. He said,

George, I wish you all the best, but I couldn’t control my constituency if I endorsed you, and you couldn’t control yours.

And he’s probably right. My people would say,What the hell is going on here if George Wallace is campaigning for George McGovern?

So he was probably right on that.Do you folks know that George Wallace went to his grave believing that the Nixon people set up that shooting?

Germany

I wanted to ask you that. There’s some writing that Chuck Colson apparently tried to put McGovern campaign literature in Arthur Bremer’s apartment.

McGovern

Oh, that’s true. We know that.

Germany

Did you know that at the time?

McGovern

Oh yes, we learned about it very quickly afterwards, and then it came out in the hearings of Senator [Samuel] Ervin’s committee. That’s when we had the proof. You know, that tells a lot about Nixon, who was not a bad President in many senses of the word. He opened the door to China. He established a policy of detente with the Soviets. He was pulling most of the troops out of Vietnam (while insisting we weren’t going to do that), and he signed the Environmental Protection Agency legislation. He signed all those food assistance bills that Bob Dole and I kept sending down there.

But he had one big flaw, and that was his personal paranoia that somebody was going to take what was rightly his away from him. So when Wallace was shot, I’m sure that Nixon had a joyous evening of celebrating that he was home free. And he ordered his staff to get out there to Wisconsin and fill that apartment of this fellow who shot Wallace with McGovern literature. That was documented in the Ervin hearings.

While he was doing that, I announced that I was calling off my campaigning for two days even though the next day was the day of the Michigan and Maryland primaries. I ordered all campaigning stopped. No watching of the polls, nothing else, just out of respect for the shooting of Wallace. That’s what I was doing.

Then I got in my car with the Secret Service and drove out to the hospital in Silver Spring to visit with Wallace. My wife, without ever talking to me, went to see Mrs. [Lurleen] Wallace. To me, those contrasting actions tell a lot, and I’ve always taken some satisfaction that—while I think it cost us a landslide defeat—we did the right thing and Nixon didn’t.

I never advocated the impeachment of Nixon. I rejoiced in it, but I never advocated it. I thought he had been duly elected, and I wasn’t going to be the one to put myself in a sour grapes position and advocate that he be thrown out of office. I didn’t advocate that his Vice President be thrown out of office, even though I was soundly criticized for not exercising more care in the selection of my running mate. Tom Eagleton was a whale of a lot better than Spiro Agnew. Those things happen in politics. I didn’t talk a lot about those things to Ted other than I tried my best to get him to be my running mate.

Knott

Could you tell us about that?

McGovern

Well, as soon as I was nominated, I called him—not right away, but a few hours later—and said I hoped he would accept, and he said,

George, I just don’t see how I can do that, but let me think about it.

The next day he waited a good part of the day, and I finally called him again. He said,I don’t think I can do it.

We had up until 4:00 to make a decision under the rules of the convention. Because of his uncertainty even during the final day, I talked to Abe Ribicoff, Hubert Humphrey, Ed [Edmund] Muskie, Gaylord Nelson, and Walter Mondale, the Governor of Florida, Reubin Askew. I talked to him right after Ted turned us down—or at least didn’t give us an okay. We tried to reach Sarge [R. Sargent] Shriver, but he was in Russia and we couldn’t get hold of him. You’d think that somehow we could have gotten through, but that was before cell phones and we just couldn’t reach him.

Four o’clock was emerging, and when I talked to Mondale, Ted, and Gaylord Nelson, all three of them recommended Tom Eagleton. Teddy gave a strong pitch for him and so did Gaylord and Mondale. So with an hour left on the clock, I called Eagleton, whom I didn’t really know. I’d never served on any committee with him. He had been there four years, but I’d had no contact with him. He had worked hard for the nomination of Ed Muskie. I didn’t really know him, but I ask him if he would accept the nomination. He said,

I’m going to say yes before you change your mind.

So I said,

Well, Tom, Frank Mankiewicz has been following this thing closely for me, and I wonder if you’d get on the phone with him and let him ask some of the questions we think are going to be raised.

I immediately left and started writing my acceptance speech. That’s another thing that got done at the last minute. It’s hard to believe that that was the way it was, but it was.So Frank asked him,

You know, Senator, if there’s anything in your background that’s going to be a problem, please tell us now, because anything in your background that you don’t want out, the Nixon people already know. And if they don’t, they’ll find out. They have the FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation]. They have all kinds of people working on this, and so if there’s anything that you can think of—What about girls? What about booze? What about any brush with the law, anything?

Tom said,

I can’t think of anything.

You know, he had 14 years of treatment for manic depressive illness, had been in and out of hospitals, the Greg Barnes Hospital in St. Louis, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, where he was treated with electric shock treatment, which was the preferred extreme treatment then if everything else failed. So the clock started to roll, and 4:00 was here, and that was it. Ted will tell you that I begged him to take it.But after all the pushing and shoving about what to do with Tom Eagleton, my instinct was to stay with him and just see it through. Yes, he’s had electric shock therapy. Yes, he’s suffered from manic-depressive illness. But we believe that he’s perfectly capable of carrying the burdens of the Vice Presidency. I think he’s a good man, and we’re going to stay with him. That’s what I wanted to do and I did, and then all hell broke loose.

Our phone finance committee resigned, you know, people who had worked their hearts out. They said,

We just can’t carry this. We have enough handicaps without this.

And so after a week, I asked Tom to step down—and that was a disaster, too. The initial appointment was a disaster, and then it was even more so when I asked him to step down after saying I was 1,000% for him. Anyway, that’s the story as I see it.

Knott

When you decided to go with Sargent Shriver as a running mate, did you talk to Senator Kennedy about it?

McGovern

Yes, I did.

Knott

Could you tell us his reaction?

McGovern

He was strongly against it, but I never wavered.

Knott

Do you know why he was strongly against it?

McGovern

I don’t know. I think it was because Sarge, who had been appointed by Lyndon Johnson as Ambassador to France, loved that job. He was reluctant to give it up and campaign for Bobby in the primaries in ’68 against Johnson, who had just named him to this Ambassadorial post. You’d have to ask Teddy whether I’m right about that, but he called me I think ten minutes before the 4:00 deadline and told me,

George, I’ve been thinking about it, and if you want to go with Sarge, that’s okay.

I spent an hour agonizing over how to get around opposition for the Kennedys. He told me at one point,

I don’t think any of the Kennedys can campaign for you if you pick Sarge.

Maybe there was something else, something in the family I don’t know about, but I know that both Ted and Ethel were upset about it. They later campaigned for me and did everything I asked, and I don’t know why they were so opposed to that.Hubert Humphrey told me that he had run up against the same thing when he thought about picking Sarge in ’68. So that would have antedated the ’68—no, it really wouldn’t. They would have had the same experience there. I think what Hubert was trying to do was pull the Kennedys back into his camp after Bobby had challenged both Hubert and the President.

But I don’t know what was in their heads. I always thought that was part of it. In fact, one of the Kennedy family told me that there were hard feelings about Sarge not leaving his Ambassadorship. He finally gave it up, but it was a hard thing to do because he loved that job and so did Eunice. You folks know as well as anybody: there’s enormous family loyalty in the Kennedys. They may have arguments with each other, but once somebody sets out on a course for high office, the whole family rallies around.

I don’t know how we would have done with a McGovern/Kennedy ticket. It still would have been a couple of northern liberals, and whether we would have done any better with the South and the West and the Joe six-packs, I don’t know. But I always thought that he would have been the strongest running mate.

Germany

How long had you known Shriver, and what was your relationship with him?

McGovern

It was good, because at the same time I was running the Food for Peace program, he was running the Peace Corps, and sometimes we would work together in countries providing food and Peace Corps help. So I knew him rather well. He favored my appointment when I became the Food for Peace Director. Jack had given him a pretty important role in helping to recruit good people in the administration, and he favored me, as did Bob. So I always had good feelings and a good relationship with Sargent. I think he would have been a good running mate—and was a good running mate—but by then we were hurt by the Wallace shooting and we were hurt by my giving my acceptance address at 2:30 in the morning after everybody was asleep but my mother.

Knott

I was awake.

McGovern

Were you? Good for you. That was a disaster, you know. We shouldn’t have permitted that.

Knott

What happened there? Why did it run so long?

McGovern

It ran because the convention was just out of hand. Larry O’Brien was presiding, but we had this rule to let people talk as long as they wanted to. It was a stupid rule. We should have just said,

This is the first time George has had a chance to talk for 45 minutes, where he’s completely in control, and it’s the most important speech he’ll ever give politically. So we’re going to go on at 9:00 primetime come hell or high water and just chop the convention off.

They were doing all kinds of silly things, like nominating Roger Mudd for Vice President and nominating Eleanor McGovern and nominating Gloria Steinem and making long speeches. They should have just been chopped off.You know the problem? We had been trying to get recognition and power so long we didn’t realize that we were the controlling power—even though we had to pay for the whole thing since the DNC [Democratic National Committee] had no money. Our campaign paid for that convention. Hubert had left a $10 million debt four years before, and Bobby had left a big debt in his primary bid. We didn’t leave a dollar in debt, and we paid for the Democratic Convention. Gary Hart or Frank Mankiewicz or I should have just picked up the phone and called Larry and said,

Cut this thing off. George is going to go on at 9:00 and Senator Kennedy is going to introduce him

—which he did, brilliantly.Knott

That was a great speech.

McGovern

A great speech. It’s just too bad the country never saw either one of us—well, I’d say possibly two million people saw us at 2:30 in the morning.

Martin

Can I ask a question about when you initially were approaching Senator Kennedy to be the Vice President? Did you have any reservations that you—as you described yourself, from a small state—taking on Senator Kennedy as a Vice President, that he would upstage you?

McGovern

I didn’t. I thought I had proved my mettle in the bid for the nomination. I won 11 state primaries—including the two biggest ones, New York and California—and I thought I could come off all right. I knew that the Kennedy name was magic. I knew that any Kennedy was going to be more charismatic than anybody else, but I never had any fear about appearing inadequate to handle the responsibility.

I thought he would help bring big crowds and excitement. He’s a charismatic figure, and I thought that would help the ticket, too. As I told you, I always thought it would help clear the air on Chappaquiddick for him if we won and he were Vice President for four years—maybe eight years. By the end of that, nobody would think he was unqualified to be President of the United States. I still feel that to this day.

Knott

He campaigned with you that fall.

McGovern

Oh yes, he sure did. The first thing I did was to ask Hubert, Ed Muskie, Gene McCarthy, and Ted to each spend two or three days on one trip. Each one would give me two or three days. That’s the way we started the campaign, with those four men going with me. It was a good thing to do, and it helped heal the wounds with Hubert and Gene McCarthy.

Ted was astounded at how well organized we were. He hadn’t seen the McGovern organization that won the nomination up close because he tried to stay out of the primaries, which is understandable, but he was astounded at how well organized we were in spite of all the problems we had had. We had good advance people in every state. We had a good grassroots organization. Everything was well organized because we had been through all these primaries. He said,

I can tell you frankly that Jack Kennedy’s campaign was never organized like this.

Knott

You also paid a courtesy call on Lyndon Johnson, if I remember correctly.

McGovern

Yes I did.

Knott

How did that go?

McGovern

It went well. He gave me some advice that I wish I had followed. He said,

George, first of all, you think the war in Vietnam is a God damned disaster. I think you’re goofy on that

—which he really didn’t, but he said that—so let’s not talk about it. Let’s just rule that out. Now, how are we going to win this campaign?

First I asked for his support, and he said,

Look, I’m 100% for you. Did you get my telegram?

I had to tell him I’d never seen it. To this day, I don’t know what happened to it, but I never saw it. Somebody must have it, or somebody must have opened it, but I never saw it. I didn’t answer directly. I said,I knew, Mr. President, that you were going to be for us if I won the nomination.

He said,

You’re going to have some of my people telling you that they’re for Nixon. That’s a damn lie. I’m for you, and I’ll do whatever you want me to do.

I said,What I’d like you to do is go to a rally with me in the Houston Astrodome.

He said,I’ll do it if the doctors say it’s okay.

I knew he had heart trouble. He said,Is there anything else I can do?

I said,

Well, if you have any advice, Mr. President.

He said,Yes. If I were you, I’d forget about that Vietnam deal, and I would just say to the people of America, ‘I want to thank you for keeping me in high office all these years. I owe this country so much. You educated me under the GI Bill of Rights. You provided good schools for my children. You have presided over a great civil rights movement that’s going to treat all Americans as equal in the eyes of the law. You’ve done so much for me. You’ve permitted me to serve in the United States Congress, the United States Senate. And now you’ve given me the Presidential nomination of the oldest political party in the history of this great country that we all love. So I just want to thank you, thank you, thank you, for what America has done for me.’

Now, why I didn’t say that, I cannot explain. That’s exactly what I should have said. He was right. I thought it sounded a little corny, so I just let it pass. But that’s one piece of advice I wish I had used over and over again.

Lady Bird [Johnson] was very friendly. I noticed that day we were sitting on the lawn outside his ranch house that he had let his hair grow clear down his back. You know, as long as the hair of those kids who had been taunting him. It was his way of showing, I’m not such a square. I think that’s what it was. And then another thing: he was smoking one cigarette after another, just chain smoking. His doctors had told him he was going to die if he didn’t give up smoking, which he did for several years.

But here he was: Lady Bird had cooked a nice steak for each one of us, sort of a small dinner steak. Somebody else cut his up, and then, as usual, he just took over the conversation. Then he’d stop for a while and light a cigarette, and then with the cigarette in this hand, he’d eat a little piece of meat, just a little bite, and if the cigarette had burned low, he’d light—he must have smoked 15 cigarettes while we were eating, if that’s possible.

Lady Bird looked at him from the other end of the table, just smiling. If there’s such a thing as a sad smile, that’s what it was. She was just looking at him, watching him smoke. I’m sure she had begged him not to do this. And I think she also figured that he wasn’t going to be around too long, which he wasn’t. He was unable to make that speech in the Astrodome. In fact, he was unable to do anything, and he died right after the election.

I have no complaints about Johnson in the election. Later in the campaign, I went down to the Johnson Library, and the press couldn’t wait to ask the first question,

Do you welcome the endorsement of President Johnson?

I said,I certainly do. I think save for Vietnam he was one of the great Presidents of the 20th century. I welcome his support, and I’m glad that he’s going to campaign for me.

And I felt that way.I never had any problem with Johnson. And Hubert went out and campaigned for me too, as did Gene McCarthy, Ed Muskie, Ted Kennedy—they all gave me their two or three days.

Knott

Did you believe you were going to win, or was there a point where you realized this was not looking good?

McGovern

After the shooting of Wallace, when I realized it was just going to be a two-way race—with Wallace’s support, probably 90% of it at least, going to Nixon—I had serious doubts whether any Democrat could have defeated him at that point. And then when the Eagleton thing erupted, I was more doubtful. But I don’t think I ever betrayed that to any worker, to any voter or any party officer. I campaigned hard, three or four cities a day, from then on. Nixon was running the so-called Rose Garden strategy, and of course we now know all of his private time was given over to covering up whatever they were doing.

Martin

We should probably move on to 1980, if that’s okay. How did you respond when Senator Kennedy decided to challenge [Jimmy] Carter for the nomination?

McGovern

I publicly endorsed him right away. I had been urging him to do that.

Martin

Were you among a group of folks who were encouraging?

McGovern

Yes, I think a number of people did. I certainly did. If we had the Carter then that we have today, I wouldn’t have urged anybody to go against him, but at that point I thought we’d be better off under Ted. I thought he’d push for a more liberal program, that he had a better international program, and that he would do better in the fall in the general election. So I endorsed him. I went to the convention and did what I could to help him. There again, I had a tough Senate race of my own on. I was startled, to put it mildly, that he didn’t do better than he did in the results.

Knott

Could you elaborate a little more on your problems with President Carter and why you thought Senator Kennedy would be a stronger nominee?

McGovern

I thought that Carter had no real pull with the Congress, that even the things he did propose, it was difficult to get action on. I thought he had very little grasp of national and international issues. I was turned off by his statement,

Government is not the answer to the problems; government

is

the problem.