Transcript

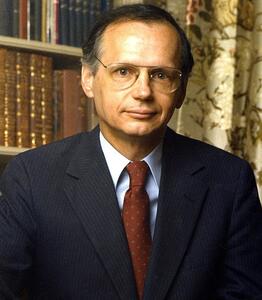

Heininger

This is an interview with Governor Richard Riley, former Secretary of Education under President [William J.] Clinton, on September 8, 2008. Why don’t we start at the beginning. Tell me when you first met Ted Kennedy, and what were your impressions of him.

Riley

I’m sure I shook hands with him a couple of times, but as far as really meeting him and knowing something about him, it was probably in 1980, when Jimmy Carter was running for reelection. Jimmy Carter asked me to chair the Platform Drafting Subcommittee for the convention, and the Platform Committee. You’re given a blank sheet of paper and you have to start, and then that goes to the platform. Senator Kennedy, as you know, was running in that year, and Carter had the votes, but Kennedy made an issue out of the platform, and he really was planning to fight for certain things in the platform. So I had Jimmy Carter, I was very close to him, and he pressured me into taking that job, which was a terrible job under those circumstances.

Heininger

Yes.

Riley

There were 15 members on the committee; Carter had eight and Kennedy had six and one (Senator Daniel P. Moynihan) uncommitted.

Heininger

Really?

Riley

[Stuart] Eizenstat was my advisor. Peter Edelman, Marian Wright Edelman’s husband, headed up the Kennedy side. So every issue that came up, like Ireland and Israel and education and healthcare, the whole world of issues, many of them were 8-7 votes. Of course, I was in touch with the White House, through Eizenstat. So that was a very interesting experience that I had. The last meeting was 17 to 18 hours long, and we had something like three or four days to get all that done, and we were at each others' throats, between the Carter people and the Kennedy people. The interesting thing about it, though, is we came out of there bonded, the committee, and some of them are my very best friends, including Peter Edelman. I knew Marian, of course, from South Carolina. Maxine Waters was one of them. We’d scream and holler all through the night, and then at the end, we all embraced. We differed on some things, but we had the majority, and of course we would win every contested vote. Then we would go to the press and there would be 18 to 20 cameras out there, and everybody was screaming. That was where the whole campaign was focused, on the platform. Kennedy, if you recall, was not real friendly with Carter on the stage.

Heininger

Right.

Riley

I was on the stage. I presided over the convention for some two or three hours, since the platform was the main thing. That was a very sensitive time. I didn’t appreciate that myself, because I was a big Jimmy Carter person, but you know, I could see then what a fighter that Kennedy was. I had followed him and knew a lot about him, but that was a real close experience, where I really saw him when he was beaten by the votes going in. But he never looked back and he fought and fought and fought, and his people did, too, and it was a very interesting thing.

I observed him. I was on the stage, as I said, and I saw when he and Carter had their kind of cold shoulder deal. That was an experience that I’ll never forget. I saw him as a determined person, fighting for what he believed in, and of course, his speech was—he got big support. He was very successful as far as his efforts were concerned, but it was not helpful to Jimmy Carter.

Heininger

Or to the ultimate outcome of the election.

Riley

The ultimate outcome. Ronald Reagan benefited more than anybody else.

Heininger

Given your experience in dealing with that, what would you have expected Kennedy to do after that loss, which was, after all, the build-up for Kennedy?

Riley

Well, you get into these conventions—and I just got back from Denver, where I was a Hillary [Clinton] delegate, at-large Hillary delegate, and we had the same kind of deal. So you have to go through those things, and I’ve been in all the conventions since this one and I have seen that happen. You have to kind of work through it. But it’s not an unnatural thing to happen, to have the clash or the person who didn’t get enough votes coming into the primaries and then all of a sudden, they have a following.

Kennedy had a tremendous following. I mean people would just fight for him. Same with Hillary. Hillary had these people with tears rolling down their faces, and it was a Barack Obama obvious victory. Of course she came around and released us all, and I urged all my delegates to support Barack Obama, and they all did but three. They said they would be very supportive of him but they felt like they were committed to Hillary. So that was the same setting there, moved forward to 2008. It was a very similar kind of situation, but things are so different now. The technology is different and you are able to put things together better. There was a real clash in the beginning of the convention this year, but it came together better. Back then, it all came together on the stage when they were speaking. It wasn’t worked out ahead of time.

But you saw what a tough guy he was and what he believed in, and I got that message completely. Then, it turns out that I became his close friend and confidant, but we both respected each other. I was doing my thing for Carter and his group was doing his thing.

Another situation that I think is interesting. My father [Edward P.

Ted

Riley] was chairman of the State Democratic party in 1960, when Jack Kennedy was running for President. My father headed up his campaign. There were others; Fritz [Ernest] Hollings was very supportive, but it was very controversial, primarily on the Catholic issue. My father went all over the state speaking for Jack Kennedy. I went with him a lot then. That was in 1960, and I was a young guy.We carried the state for Kennedy, by 11,000 votes. I remember my father calling to tell headquarters, and had Bobby Kennedy on the phone, who yelled,

It’s Ted Riley!

And screaming, he said,We’re going to carry the state! It’s going to be close!

They thought they were going to lose South Carolina and they were going to carry Mississippi, and it turned out the other way around, as I recall. Anyhow, they needed us. That was the middle of the night and we carried the state, but barely. We haven’t gone Democrat since then, until Jimmy Carter ran, and I was his campaign chairman for South Carolina in ’76, and we carried the state. So we carried the state twice for Democrats since [Harry] Truman, no [Franklin] Roosevelt, and that’s the truth. Once my father was Jack Kennedy’s chair and once I was Jimmy Carter’s.Heininger

Well, it sounds like there is a great support for the Riley family in this state.

Riley

Yes, that’s what the Rileys think. That’s not true, but that’s what they think. Ted Kennedy loved that story, and every time, when I testified before him—you know, it’s a lot of tension a lot of times with differences with the Republicans and everybody is fussing and fighting—and he would say how welcome I was. Then several times, he proceeded to tell this giant crowd about my father heading up his campaign for his brother, and he never forgot it. So that was another close connection we had, back to 1960, which meant a lot to me and it meant a lot to him. And we did carry the state. As you recall, that was a very close election. So that’s my experience.

He and I have had very serious interests after this issue in 1980, but then when I went to Washington, of course, in ’93, and I headed up President Clinton’s transition for sub-Cabinet positions. The Democrats really hadn’t been in power for so long, except for the four years of Carter, and he was somewhat anti-Washington. He had mostly Georgia people.

Heininger

It had been a drought.

Riley

Yes. So I had that very difficult job, and worked with key leaders, but we’d had résumés, something like 3,000 résumés a day were coming in, and we had to separate them out into education, justice and whatever. I know I talked to Senator Kennedy several times during that time, because he’s very close to Clinton and he was certainly a key friend we had in the Senate. I talked to a number of other Senators too. I remember one thing that I was especially interested in—and President Clinton was—was Jean Kennedy Smith being an Ambassador to Ireland. Boy, did Ted Kennedy like that.

Heininger

Whose idea was it? Did it emanate from the family or did it come from Clinton?

Riley

It came to me and then I had a committee of about 15 people, which included representatives of Hispanics and African Americans, and we then would go through and knock things around, but it came to us and we were very supportive of it. But there were others who were interested in it. I mean, every Irish American is interested in that slot. But it came from Clinton. I don’t know exactly. He and Kennedy were close, and of course Hillary was in the middle of all that, too. That was before I was going to be on the Cabinet. I was just there as a close friend of Clinton’s. He and I were Governors together.

Then he asked me to go on the Cabinet during that period, those couple months of transition. Then I really did start working, when I was putting the Department of Education together. Of course, the previous leaders had talked about eliminating the department, and that had been a source of discussion for a number of years. The elder [George Herbert Walker] Bush had not put in a whole lot of infrastructure of assets. It had an old, out of date kind of computer system. We had eight or ten different systems and we had to integrate all that. It was kind of let slide because they were trying to get rid of the Department.

Boy, did I have help out of Senator Kennedy. He was really helpful from the very beginning, and several of our key employees that I had working for me were from the Kennedy School and Harvard. I had gone to the Kennedy School, by the way, in 1990, in the IOP [Institute of Politics] program, and taught there for one semester. And I saw him then, too, during that time when I was up there. I had that connection with the Kennedys also, that I had taught in the Kennedy School.

Heininger

Well, let me back up for a minute. Given what you saw in 1980, and given the conflict between Carter and Kennedy, did you expect Kennedy to run for President again? Did you expect him to go back to the Senate, lick his wounds and kind of retreat to the Senate and focus on the Senate, or did you still see him as a potent Presidential force?

Riley

I didn’t. No, I felt like he would go back and be a leader in the Senate, as he was. Of course, he lost that election and it’s kind of hard to see that come out the other way. We all thought Carter was going to be reelected, and then he could have been a voice out there and probably would have. Carter, of course, couldn’t run a third time, and he—that would have been the right, logical thing, to see him in that election if Carter had won. Politically, he would have fared better probably, if he’d had a good southern moderate like me work out his differences with Carter, and then be kind of lined up to take a role in four years. He doesn’t play that way though, that’s not his style. He was in it to win and he was in it to make a statement on the various issues, and he did. You really had to admire him for that, and I always have.

Heininger

At that point, did you see education as being a big issue for him?

Riley

Education had always been a big issue for him. He had always, as I followed it over the years—of course then I was Governor for eight years in the ’80s—he was a big supporter of education then. I used to see him from time to time, and appear before committees as Governor, and he was always very supportive. He and I had a similar view on public education, that it was absolutely critical to give the kind of support it needed to move it forward. There was always a large group of primarily Republicans who were for the vouchers and the shifting money to private schools and all the other ways I always considered to be harmful to public education, and so did Senator Kennedy. He and I were always together on the big things, no question about that. He was always very supportive during appropriations time, had support of education all through the ’80s, and I got to know him very well and appreciate him. He and I were friends then and respected each other I’m sure and had worked together on a number of things, at a distance but together.

Heininger

In looking at the ’80 election, there are a lot of people who say that the principal reason that Kennedy challenged Carter was on the lack of movement on national health insurance. Given that you dealt with the platform issue, did you see the biggest stumbling block in their relationship being healthcare, or was it much bigger than that?

Riley

Healthcare was clearly the biggest thing they were talking about. Carter was in a slump during that time, and I’m sure Kennedy felt like he could give a boost to the Democrats and turn that around, but healthcare was really—in his speech, of course he talked about education and he talked about working people, and he was always so strong for working people. Healthcare then and here again this year, healthcare is still there, and it was the biggest issue between Hillary and Barack Obama, even though they’re very similar. I’m sure he and Carter could have been similar. They were both hardheaded. Honorable, both of them were very honorable, but hardheaded.

Heininger

Talk about personalities that didn’t quite mesh.

Riley

That’s right. Being a little person watching all that happen, you really saw people who believed in what they were doing, and were fighting for their view for the right reasons.

Heininger

And yet you could also go back and look at this and say, if healthcare was the principal thing dividing them at that point, it still remains. We haven’t accomplished national health insurance, it still remains a problem, yet look at what has been accomplished in education, which wasn’t necessarily at the very top of the agenda at that point. There’s been a sea change in the federal role in education.

Riley

Education really started to change. Of course, the real change occurred in the mid-’60s, when Title I and all that came with LBJ [Lyndon B. Johnson]. But then in the ’80s education reform happened, and that’s when I got into education so big, when I was Governor here. And that’s why Clinton and I worked together on education reform, as we call it. It involved everybody doing more, including the Federal Government.

Then A Nation at Risk came out in ’83, and my big education reform here was ’82, ’83, and ’84. Then it all kind of came out of the South, southern Governors, southern moderate Governors really pushing for making major headway. Of course, the South was, as Roosevelt said, the major problem in the Depression years, economically. And now the South, in a lot of ways, is the engine that moves America’s economy forward, and I give all that credit to education.

But we had treated African American kids poorly over the years. I was very much embarrassed about that part of the South’s history, and ever since I’ve been in politics, I’ve been trying to do what I could to turn that around. And education was a way to do it. Healthcare is connected to all that too, as also are a number of other issues, but education is the main one. All of those things, Kennedy and I were just side by side on. And I can’t think of anything that we have a serious disagreement on. We were just very similar on education issues and really, he supported Clinton’s program generally across the board.

When we went in, in ’93, of course he was the chair of the committee, and that was absolutely critical then, how we got it set up and what we made our major priorities, and Goals 2000, the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, all that forming standards for all the 50 states, which is major in my judgment. It was a major thing we had to do and we did it during those eight years of Clinton. We couldn’t have done that without Kennedy. He was absolutely critical in all that.

The standards movement is really somewhat of a conservative movement. You can’t have accountability without having standards. You don’t know what you’re accountable to. Then, the way education works, with every state having the education responsibilities, you had separate state standards for all 50 states. We gave incentives, of course. There were heavy incentives for states to get into the standards movement, plus the President was promoting it. All the states were talking about reform and so the Governors were for it. But Clinton was very strong, and I was too, for the standards movement. As I say, Kennedy was critical during all that time, but then was very supportive of funding things like Title I and TRIO [Federal Early Outreach and Student Services Programs] and then we came in with GEAR UP [Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs] and some programs during that time.

As I recall, you had the question about the difference between the House and the Senate after the [Newton] Gingrich years. Of course it shifted then, and Jim Jeffords became the chair of the committee, and Senator Kennedy was ranking Democrat, and was tremendously effective. He and Jim Jeffords were very close, and we were real lucky with that. Jim Jeffords basically supported what we all supported, too, and then he eventually switched, as you know, and then turned back Democratic.

During those years, ’93 and ’94, Kennedy was there, and then ’95, at the end of our term, the Republicans were in the majority. However, of everybody in the House and Senate, Senator Kennedy probably had more impact on education than anybody, Democrats or Republicans in either House. He was the person there who was so helpful to us, but I mean he was the guy, too. A lot of the stuff came from him to us. He had his strong ideas about education.

There are some questions here about his staff. His staff was clearly, in my judgment, the best staff on the Hill, House or Senate, and there are some very good people over there on the staff. You have a different view of that when you’re up there working with them, from people out in the field, but very good people. I was always very close to the career people in education and others, and got the political people to work with them all the time. That hadn’t happened under President Bush. But always, his staff—a number of his staff worked for me and then went with him, or worked for him and then came with me. I mean his staff and my staff people were just as close as they could be, and they worked together and did papers together, white papers and points about education issues. He had these super people on staff and still does.

He has an attraction for very bright young people who believe that there is a role for government, and that education is an important function for this country. He draws these bright young people in. I mean, he can almost take his pick in the country, of bright young people who are committed to the kind of thing he’s committed to. He did that. He had these wonderful people, and I did, and they all worked together. A number of my people came from the Kennedy School also. So that was a great experience I had with him, and then whenever I testified, he was always so supportive. Somebody would harp on me about something and he’d harp right back at them, and I just knew I had a lion in my den when he was sitting up there. That was so helpful and comforting, because the Gingrich years were tough years.

Again, they were trying to do away with the Department, and we were trying to maintain the Department and improve it, and he was too. Fortunately, I’m talking about the House and the Senate, things would come out of the House and it would be very difficult. They would cut our programs and cut things out, and then we usually had very good help coming out of the Senate, and Senator Kennedy was involved in all of that.

We had some Republicans who were friendly to improving education in a meaningful way. I think [Mark] Hatfield was Appropriations at one time, and he was always very supportive. Arlen Specter, always very supportive, a very good friend of mine, so was Senator Hatfield. I mentioned Jim Jeffords. So we had—they were Kennedy’s good friends too, but we had people like Chris Dodd, who were real solid supporters on the committee. Those committees, as you know, are very important in Washington, and the committee that handled education—there was just no question that Senator Kennedy has been the leader of that committee no matter who was in control of the Senate, and everybody accepted that. I mean it was just understood that he was the leader there, and of course that was very comforting to me.

Heininger

How did your views on standards evolve?

Riley

Well, I always was a student of education here in the South, and really determined to do what I could as Governor. My campaign was on education and everything else. I will tell you, in my inaugural address, on the second four years—they had changed the Constitution, so it enabled me to run again. In my inaugural address, the second one, I decided that I wanted to discuss a baby that was born that morning, and then talk about that baby’s life in South Carolina. That had all kind of complications; would I use a baby who was black, white, Latino, a big city, small town. We came up with a baby born that morning from a middle-sized town from a working family, a white baby, named John Christopher Hayes.

And so my whole speech was about John Christopher Hayes, and how if we didn’t change education and all that, he didn’t have that much of a future; but if we did, he did. But healthcare was involved in it, and all the other related issues, and economic development and so forth.

During those years, I was very much into all of that, and I was certainly one of the first Governors to come out with a really comprehensive education plan, said to be the most comprehensive of any Governor by the Rand Corporation. And Kennedy and I, we were partners then. He was into everything we were trying to do, but it wasn’t like liberal and conservative, it wasn’t just like pouring money in. Of course we had very serious involvement for parents and for professional developers, developing accountability as best we could. You wouldn’t get your arms around education though, until you had standards. You had to determine what were the goals for education.

[BREAK]

Heininger

This is a resumption of the interview with Governor Riley.

Riley

Standards, you asked me about standards.

Heininger

The federal approach up until then, which was set in the mid-’60s, had been that you would fund through Title I, you would fund school districts with money for less advantaged children.

Riley

That’s right.

Heininger

But then, how do you get from there to establishing standards, because this was the real sea change?

Riley

It was a sea change, and it’s the most important thing, I think, that’s happened to education over the last 50 years. As I say, while Ted Kennedy clearly is a liberal person, and he thinks that there’s a role for government and you need to fund it, he was very strong on accountability and very strong on standards, and I was too. Southerners, southern conservatives, supported that. However, we also supported funding it, and somehow it would fall off the wagon there, but as I say, it’s a conservative move in terms of education.

Heininger

It is. It’s not a liberal move.

Riley

It’s not a liberal move, and it’s accountability. You can’t have accountability without standards. A lot of people think Ted Kennedy, being a liberal, would say,

Just throw money at it.

That’s a false definition of liberalism. He was very strong on funding public education in a good way, but he also was very strong on accountability, and I was too. We had a complete meeting of the minds and spirit on the whole issue. The first thing is we both believe in the importance of public education. That’s critical. Public education really got its start in Boston, and Ted Kennedy follows that mold. Standards, to me, are the big issue, and the Federal Government at that time—we used incentives and support rather than punishment to develop state standards in each state.No Child Left Behind is probably weighted down with top down regulations and requirements, and then punishment if you don’t perform. I supported No Child Left Behind, the idea, and I said that you’ve got to have a certain amount of discretion on the state level. If you don’t, our system just simply doesn’t work because it’s so different from the mountains of Kentucky and downtown L.A. You know what I mean? You have very many differences in this country. However, standards should be statewide, and they are. That has caused problems now, with No Child Left Behind, because of the national required testing, and yet the standards are different from state to state. South Carolina has very high standards. I always have supported high standards, and so does Massachusetts. As I say, we were together.

Heininger

But not all states do.

Riley

Not all states do. Texas and North Carolina are lower, and so they fare better in No Child Left Behind. I mean that their kids are reaching proficiency level faster than ours are, and it’s not a good measure, and all of that, I hope, is going to be changed. I think it is. I think that in the reauthorization, certainly if Obama is in there, he’ll be a very strong supporter of that. The idea of having national standards is of interest to me then and now, and with more and more national involvement—because it’s so unfair now, state by state. I think we ought to take a lot of the punishment out and put in incentives, and if you work hard and make improvement, you might still not be up here, but you’ve improved. I would bet you that Senator Kennedy is right in that same boat as far as reauthorizing. I’ve talked to his people about reauthorizing it, and the very same things I’m concerned about with No Child Left Behind, he and his staff are concerned about.

Heininger

When you came in with Clinton, did you think that there was any chance of getting national standards, or was it just off the table from the very beginning, that it was going to have to be state standards?

Riley

There was no thought of national standards then. We had a national goals panel to analyze what was happening but that never really—it kept having lots of problems. It was just complicated. Education is complicated in this country, with it being the state responsibility.

Heininger

And more to the point, of being funded by local taxes, so there’s local responsibility.

Riley

And that’s so unfair.

Heininger

Yes.

Riley

The property taxes primarily and all that. All those complications are out there and somehow it moves along. But I think it’s in better shape as it has moved along, and that has been aided tremendously by standards. Now, there are a lot of people who are thinking people on this subject. Mike Cohen for example, worked for me. He’s the head of Achieve. Mike thinks that rather than having national standards, you ought to have standards from groups of states that are similar enough to be the same, even though they’re not identical.

Heininger

Comparable.

Riley

Comparable standards, like the Southeast has comparable standards, and the West. I’m very comfortable with that. I don’t care about just coming in and saying the Federal Government says this is what the standards are going to be. I’m not troubled by that. I think we’re about ready for that. How you reach standards, then, remains with the state. That’s what’s important, how you reach them, and that’s in every city, in every school district, every school, but it’s a very complicated mix. Therefore, when I was Secretary, of course having been a Governor was a tremendous help. Then I was a state senator in the state house before that. My family has always been very much involved. My father represented the school district here, as a lawyer, a big school district, and so as a young lawyer, I was handling a lot of small school things but learning about education. That’s a big help.

So when I came to Washington, I had good background in understanding the complications of it. But then you run into the Congress over here. You know what I mean? That’s a whole different world. Most of those people haven’t been Governors and haven’t been state legislators, and you try to sit down and explain to them about the importance of having standards and the importance of having testing and having testing that’s helpful to children and not harmful to them, and a lot of them don’t go with that. I mean, they’re into money.

Kennedy has always been very interested in education, from top to bottom. He’s interested in what works best and why, and what they’re doing on the local level as opposed to state, and that kind of thing. Part of that is his basic interest, as I said, in public education, but part of it is that he surrounds himself with these bright, young, forward-thinking people who really do know education, and they are interested in improving things, and willing to hurt for it. I’ve always said that everybody favors education but not many people are willing to hurt for education. Ted Kennedy is willing to hurt for education, and that’s the truth, and so was Bill Clinton.

Heininger

Good point.

Riley

He would go the distance. Everybody says they want to do this and do that, and that they favor some funding, but not enough to really move things up, and he’d go the distance. It was just a pleasure to work with him.

Heininger

What was the states’ response when the Clinton Administration came out with Goals 2000?

Riley

Well, we were working closely with the states at that time, and the administration before us came out with

Save America’s Schools

or something about America. They’re big on America, the Republicans. They had a program that they were going to have a model school in each Congressional district, that was their program, and it had a head of steam. Of course, the Democrats then were in the majority and killed it, but that was their main program then.Lamar Alexander was and is a friend of mine, and he had some other ideas, but the standards movement was being discussed by everybody then. But when we came in, in ’93, I don’t know that any state had standards—maybe a couple, one or two states that were working with it—but it was well discussed as a major move to improve education and that we could only do so much until we had standards. Conservative Republicans basically, as I say, supported the standards movement, as it was called, and that’s one thing that enabled us to pass Goals 2000. And the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act was where we really got the incentives now, to put in standards. Incentives work in education, because it’s self-improvement. Punishment doesn’t work generally.

Heininger

Which is ironic, because incentives, theoretically, ought to be a Republican position.

Riley

No. Incentives are generally Democratic ideas.

Heininger

But they ought to be Republican. They’re a reward for good performance. That’s a very Republican notion.

Riley

Oh, yes.

Heininger

If you work hard you are rewarded.

Riley

You get paid off.

Heininger

You get paid off, right. But you’re right, they’re not. They ought to be, but they’re not.

Riley

Their idea is that government gets in the way. Of course, government is in the way with No Child Left Behind, big time, and Kennedy was very much involved in putting some stringent rules in that. When we came out of office, the Clinton years ended. The impact that Senator Kennedy had during those years, I’d say more than any other House member or Senator during our eight years there, no question about that to me. Education was red hot. Every poll that you took, education was one or two. Jobs might have been close, but education was at the very top of every poll.

Of course, [Albert, Jr.] Gore was strong, said the right thing, but he hadn’t come up as a Governor, and he didn’t know how to say it as well as [George W.] Bush did, and that used to really bother me, because he was for the right things, right down the line. I’m a great supporter of Al Gore. I just think he’s a super person and public servant, and he ran a great campaign and he should have been elected because the Democrats were very hot at that time.

When Bush got elected, he had sense enough not to include vouchers in No Child Left Behind. But we had laid fertile ground for a major accountability education measure to be passed. First of all, you had to have standards in place. We had standards in place in all 50 states. The only state that didn’t have it was Iowa, and they have standards in local districts; it’s required in their constitution, but they had standards too. All 50 states had standards, everybody was supportive of education. So when we came out, it was rolling, and then No Child Left Behind was the creature of that. They moved that thing right through, but Bush had good advice:

Don’t stick vouchers in there; if you do, then they’re going to kill it.

And he did keep vouchers out. That was a wise political move. That was difficult because vouchers were the big issue with Republicans.Heininger

It’s very interesting because if you talk to some of the Republicans now, many years after the enactment of No Child Left Behind, some of them will pooh-pooh what the Clinton Administration did and say,

Well, they didn’t do much of anything, and it took us coming in to really get at the issue of accountability.

But it strikes me that what they ignore is that you couldn’t get to accountability until you had standards. From where Clinton started when you came in, with a very limited role in federal education, a limited federal role just pumping money in through ESEA [Elementary and Secondary Education Act] to where it is at the end with these standards, you couldn’t have done accountability without that process in between.Riley

Well, in the Clinton years, we did not have a slogan like No Child Left Behind.

Heininger

Never underestimate the power of a slogan.

Riley

They’re very good at that.

Heininger

They are.

Riley

Of course that’s Marian Wright Edelman’s slogan. They took that from the Children’s Defense Fund. We didn’t build it around a slogan. We really built it around policy and developing standards and measuring. The Clinton years—I think it’s a tremendous record, I’m very proud of the eight years we were there in terms of education, all of which Senator Kennedy should have been very proud of, too, because he was in the middle of it. The screaming and hollering wasn’t going on. It’s not like we were at war. They’d stick vouchers out there and then we’d kill it, and then they’d stick in some of these other things.

Heininger

Like trying to shut down the Department of Education.

Riley

It wasn’t a time when it—when you look back at it, it was kind of smooth going, which is what we wanted, which is what we hoped for, and education should be that way. There was never any big war against it. They liked standards. Republicans probably like the standards movement more than Democrats. The Democrats were very nervous about that, especially the black caucus and the Hispanic caucus. They wanted to make sure they had opportunity to learn standards—if you recall that—which made a lot of sense.

Heininger

Which was interesting because they were big proponents of No Child Left Behind. They were big proponents of accountability. So there was a real 180-degree switch.

Riley

Well, the black caucus and Hispanic caucus favored more money for education, improving teachers and all that, before you started standards and measuring. The other side was, if we wait on that, we’ll just wait forever. We’ve got to get standards in there and then start seeing what’s needed, and then put money in to help move it along. And those are two very legitimate points.

I remember I got chewed out in one of the first meetings I went to. I had a very good relationship with the members of the House Education Committee, with Dale Kildee and all that group, and Bill Ford was the chairman. In executive session, the Committee chewed me out because they were for the opportunity to learn standards—but we were for standards, and then bringing the opportunity in to meet the standards. I tried my best to convince them that that was the way to go, but they screamed and hollered and screamed and hollered, and it was all Democrats. It was a closed meeting.

Then they came around, and the reason they came around was because it clearly was the right thing to do for the kids that they were concerned about. We could scream and holler about opportunity to learn standards all day long, but until you knew who was doing what and who was making progress and why—Kennedy was a big help in bringing that around because he, of all people, was perceived to be the strongest liberal there in the Senate. He was for standards and accountability, and then doing more from the Federal Government standpoint, and that made a whole lot of sense.

Heininger

But at that point, by the time you get to the end of the Clinton Administration, did you have a sense that Kennedy was satisfied with the progress that had been made, or did he want more?

Riley

At the end of the Clinton Administration, he was always dissatisfied with the progress that we were making, every month. That was just clear, and that’s part of his nature, to move things forward. If he was ever satisfied, it would never move forward.

Heininger

Then there’s a problem.

Riley

He was always ahead of the game, and I enjoyed that relationship with him. He was a tremendous help to me. But he would come out for more than we would sometimes, which was great. We loved that. And then they might settle to where we were. But he was never satisfied.

Heininger

Then how do you explain his working with Bush to put into place, under No Child Left Behind, a system that is basically oriented around penalties for not making progress, versus the Clinton approach of providing incentives, top down incentives, and assistance to help lift up? Why did he go with it?

Riley

That’s hard to understand, but part of it is that education was perceived to be very positive at that moment, and it was the time to do something, and that was clear. Kennedy, he’s a student of history and he saw. We had the standards in place, it was a time to really do something, but it was a mixed bag out there. And then Bush got some good people involved in meeting with the House members and meeting with the Senators, to try to come up with something. Some of the House members were very much involved in putting some of the stringent requirements in there. George Miller was a strong voice for that. The things that they were for, they were for them for the right reason and they needed to be dealt with. I have said that, in my judgment, No Child Left Behind was a transitional thing. They were trying to get everybody’s attention, and then fall back to a sensible plan for improvement.

Heininger

But that hasn’t happened.

Riley

It hasn’t happened, but it hasn’t been reauthorized yet. It’s been held up.

Heininger

That’s true.

Riley

And so it will be reauthorized probably next year, and that’s why I keep telling people that next year is going to be a very critical year for education, and God knows I hope Senator Kennedy’s health permits him to be there, because he’ll be needed. There are some great things in No Child Left Behind. For example, for the first time, pulling out scores on minorities, poor kids, to see the difference there.

Heininger

The disaggregation of data was critical.

Riley

Yes. Everybody knew it, but what kind of progress are they making? The overall difference in standards is a big problem. The measuring is a problem because you test the third grade here this year and the third grade next year, and it’s different kids. You ought to test the third grade and then test the fourth grade and measure improvements, what I always called it, and I said that in the beginning, that they ought to measure improvement instead of their ranking—

Heininger

Of the same kids.

Riley

—in terms of proficiency. I think that, and I think they’re going to do that. There’s a lot of feeling that they’re going to measure—they might measure the other two, but I think they’re definitely going to measure growth as the key index for who’s really got a good school. That makes so much sense to me, but that’s another one of these top down things. There were about two dozen issues out there though. The testing hasn’t worked out well, but it’s sure gotten everybody’s attention, if nothing else.

Heininger

Were you surprised at the role that [Barnett A.] Sandy Kress played, with No Child Left Behind?

Riley

He played an important role, and he was a Democrat, so he was trusted. He kind of put things together more, I think, and came up with ideas. I don’t know that, though. I wasn’t working directly with him, of course. That was after our day. But I followed that and saw him in the middle of all those meetings, and the people were saying, the Democrats were saying, this guy is—one thing, they pulled vouchers out. That was the big thing. You do that and then you can get the Democrats to come pretty far.

Heininger

Do you think this could have been done? Aside from whether it might have been a better bill, could Gore have done it, or is this like it took [Richard] Nixon to go to China, that to get accountability through, it was going to take somebody like Bush coming in?

Riley

Well, I think Gore and Kennedy had a giant role in that. If he had been there, they would have come out with a very strong accountability bill, because it was the first time you could really do it, and I think they would have thought out a lot of those regulatory things that ended up causing problems. I make a speech on education now and ten hands will go up, and every one of them saying,

I pride myself on being a good teacher and I can’t teach. I can’t teach what ought to be taught. I’ve got pressure on me to practice for these tests every week, and it just commands everybody’s attention, everybody’s everything.

Parents, the same thing:My kid hates to go to school and taking all these tests.

And they’ve got the teachers just worried to death that they aren’t going to do well, and the school will get hurt.When we had our education reform here, we would identify the school that had grown the most in terms of grades and so forth, and they would fly a flag of excellence, and they might be the poorest school in the district, but they had made improvement and boy, they were proud of that. Instead of beating them to death and taking money away from them and identifying them as failing, they were excellent. It’s just a different way of looking at it.

I’m curious as to where Senator Kennedy will fall on all that, but I think he’ll be right there. I know he’s for measuring growth. I’ve talked to Roberto [Rodriguez], his education guy, a very bright guy, and he’s his main person on that committee, and I know he’s for measuring growth and he’s for making standards fair. I used to say, when they’d talk about tests, that you should never give a child a test that’s not designed to help that child, and that’s a pretty good, safe thing to say. The test ought to be for the purpose of helping the child.

To finish off on that thought, when I say to help the child, I mean to have a test be diagnostic. These tests aren’t diagnostic. They give these tests and bam, they’re gone, and then they read the paper of how they did. The purpose of tests ought to be to help the teacher, the parent, and the kid know what they need to learn and what they haven’t learned well, and that can identify a teacher’s weakness. A teacher needs to learn how to teach this certain thing better. So the phrase I always use is

diagnostic testing,

and that means helping the child. If you have a test that’s diagnostic, it’s designed to help the child and the teacher. Now, we’d really better get into some higher education.Heininger

Yes, higher education issues. Tell me about the whole student loan crisis issue.

Riley

Well, that was a big thing. It was 1992, I guess, when they passed the higher education legislation. We came in, in ’93. It had just passed.

Heininger

It had just passed.

Riley

And it set up tools to deal with defaults. Defaults had gotten out of line. As I recall, when we came in they were about 22 percent, and that was billions of dollars. But we had the benefit of the new tools, Clinton and all the other folks—and that was a big thing. Ted Kennedy has always been big on direct lending and student loan access, and to help the student and parent out, but we really went to work on defaults, and that wasn’t easy. I mean that’s very tough stuff, but we got it down to like five percent, and now I’m always very proud of that. That was something that we really did. That was hard work, and Kennedy was a big help in all that.

The direct lending was always a big issue. Senator Paul Simon was a big proponent of direct lending. He and Kennedy were close and he and I were close. That saved students a fortune. I’m telling you it was billions and billions of dollars, and people don’t realize it. Of course, there were two schools of thought. What I always hoped for was to get direct lending up to like 50 percent, and to have a fair, level playing field. But the real proponents of direct lending wanted to take it to 100 percent and do away with Sallie Mae and all the banks, everything else. I was a strong fighter for direct lending, to go as far as we could go, and we got up to like 32, 33, 34 percent or something, and then, of course, it has come back down since because they really hadn’t pushed it at all. In fact, they’ve done everything they could to harm it.

Now, with this recent passage, it’s reemerging, and so I think with direct lending, there is some serious thought about all loans at some point in time being directly from the Federal Government. What I always wanted, I never did think that was going to happen, because I knew the banks, Sallie Mae and all that, had such a strong lobbying power, that what we should really seek is fair competition between direct lending and them, and if they could come up under what we thought was fair with direct lending, then you know that’s good competition and it would keep everybody kind of honest. But the real direct lending believers think it ought to be all direct lending, and I don’t think that’s the direction they’re headed.

Heininger

Did Kennedy want a hundred percent direct lending?

Riley

Kennedy was a strong proponent of direct lending, and you had to be philosophically in favor of going the distance, and I guess everybody thought I was too, but I never thought we’d get there. I was for going the distance, but I would have been happy at 50 percent, I’ll just put it that way, and I would tell people that. I was for direct lending, and I thought, No question, it was a major savings to students especially. And it worked well, and I think it has done more—I’m telling you the numbers, it’s like $15 to $16 billion over four or five years. I’m sure you’ve got those numbers somewhere, but it is amazing how much money that saved, for the work we did, and never did get it to go be above 34 or 35 percent.

Heininger

Had Clayton Spencer worked for you?

Riley

Who?

Heininger

Clayton Spencer, who did higher education issues for Kennedy. Or Ellen Guiney?

Riley

I knew Ellen very well, and I knew him. I knew him, but my people worked with him, the staff, more than I did.

Heininger

Was your contact mostly with Kennedy himself?

Riley

Yes, mostly Kennedy himself, but my people were in contact with his people.

Heininger

Then Mike Smith and Tom Payzant were mostly working with the staff members?

Riley

Yes. And then, of course, Tom was K-12, and our higher education people would be working with Spencer and Ellen, but we were into direct lending big time. That was a big issue. Another issue during that time that affected money, you know there was so much pressure on us getting additional money, that we were trying to figure out ways to get money, and direct lending was one of them, and we could show we could save these billions of dollars. We put a couple billion over here in Title I or Pell Grants or whatever, and it would balance out to everybody’s advantage.

The E-rate was an important issue also. Of course, Kennedy was a big supporter of that, but that was a way Al Gore was really my main supporter, and Clinton of course. And that was in the FCC [Federal Communications Commission] first. I testified twice before the FCC, and then it came to the Communications Committee, I believe. It didn’t go to Education, but it ended up with an enormous amount of technology infrastructure going to public schools and public libraries across the country, with no new taxes, so to speak, when it just goes in your power bill.

Heininger

How important did Kennedy think technology was for schools?

Riley

He understood the importance of that. That’s changed a lot since we’ve been out of there. It’s just gotten real big now, and I’ve gotten real big into it myself and I’m sure he has too, but he was always. As I said, he was forward thinking. You couldn’t be forward thinking without understanding the value of technology in terms of teaching and learning. I think some of the real interesting programs out there now involve lots of technology use. Young people now, they are into learning that way.

Heininger

Yes, they are.

Riley

We have to understand that.

Heininger

They think if it’s not on the Internet, it’s not true.

Riley

I’m telling you. It’s amazing how they do. I’m going to see a school in California next week, a school that got started in Napa Valley called New Technology High School. Every kid has a laptop and teachers are taught to teach, but it’s built around project learning. This is building around four or five kids working together on projects and learning, teaching each other. One is going to write it up, one is going to present it and one is going to do this, one is going to do that, and knocking back and forth on who is going to do what, and if somebody wasn’t doing their part, they could vote them out of the group.

Heininger

My kids went to schools where everything was projects.

Riley

It prepares a kid for what’s needed out there today.

Heininger

Working in teams, absolutely.

Riley

Well, you have to have the content, you have to have the academic learning, obviously, but these tools to use learning now involve technology, communication, and working with people, respecting other people’s views, weighing views of a lot of people. You go out in the world and try to get a good job nowadays, not to mention after college, but after high school, you’ve got to show those kinds of skills. So I really think there’s a lot that we can do in that direction. But anything like that, Kennedy was a student of what was happening, and what we need to do to move it forward. He was not one to back up at all ever, on anything really, but especially education.

Heininger

Well, one thing, tell me about GEAR UP. GEAR UP is another whole piece of the different population.

Riley

Yes, it is. It’s a fascinating program and, of course, it came out of the Clinton Administration. He was very supportive, extremely supportive. Gene Sperling was our main guy on that, and when we were trying to get money for GEAR UP, Gene Sperling pushed Clinton and Clinton would come in with money. You know how that worked. Gene had a brother who worked in a middle school in Chicago or something.

Heininger

A personal connection.

Riley

A personal connection, but was very effective with it. I mean he really believed in it. The idea of having these bright college kids, like one of the five-year programs at Berkeley, and these very bright college students at the university would go out in these poor neighborhoods and team up with these middle school kids. They could do so much more than a teacher could. But the program just makes real good sense, and that’s the kind of thing that when Kennedy and I would sit down for a casual talk, that’s what we talked about, those kind of things, like GEAR UP.

I’ll tell you another thing that we were into and he’s very supportive of is college work study. We changed college work study. It used to be—drive a school bus or working in the cafeteria, then you’d get some federal dollars and the school would have to match it, whatever. The way to really help poor kids, though, is to help kids go to college, and so we got that changed to where if you mentored or tutored a kid in elementary school who was way below reading level or math level, then you could get college work study. We had thousands of young people then who had become tutors of these young people, which is a similar concept of GEAR UP. Again, college work study.

I remember I was out in southern Illinois, and Ted Sanders—do you know Ted Sanders? He’s a Republican. He was in the first Bush Education Department. He was president of a university in southern Illinois, and I was reviewing a program they had on the college work study, and they had 50 to 100 young people who were doing that, tutoring young people. The point they made to me is about half of them changed their major and shifted it to education. They just couldn’t believe how they could impact these one or two, three children that they were tutoring. They’d be in history or whatever and they would decide that they wanted to be teachers. Isn’t that a good thing to look at? But Senator Kennedy was very supportive of all of those forward thinking programs.

Heininger

What about the classroom size reduction, he attempted to get that through?

Riley

Well, the more people know about that and think about it, the more important it is. You get into this individualized teaching and learning, you know every kid learns differently, you can do so much more with technology, with that. Class size, after all the politics of it, of course, Clinton always pushed for it, so did Ted Kennedy. It’s turned out, people really do believe in that now, all sides, and it’s this idea of the closeness of individualized teaching. Like the school I mentioned, there are classes with no more than 20, that kind of thing. It just makes good sense. It was perceived at one time as what the liberals favor, and yet you talk to a teacher and they say,

We cannot teach 37 students in the second grade.

My daughter is a teacher in Georgia, in the public schools, in Roswell. She has a partner teacher. She teaches one week, her partner teaches the next week, and then she teaches and her partner teaches.Heininger

Oh, wow.

Riley

She’s got children, teenage children, one daughter is just going to college, but she couldn’t teach if she had to do the whole deal. Boy, the parents love these two teachers, and they both work all the time. Even when they’re off, they’re working.

Heininger

Of course.

Riley

It’s like having two teachers. So there are a lot of things like that you can do. That’s an administrative thing. It’s complicated for the administration of the district. They send down what the principal has got to show for this, and that makes them have to do it twice instead of once. You ought to be able to get over those administrative hurdles and do some innovative things like that. I’m a great believer in smaller classrooms and individualized—a move towards individualized teaching and learning.

All right, Pell, we didn’t go much into that. That’s always been a big thing and Senator Kennedy was always way out front in Pell. He and [Claiborne] Pell were good friends, too. The HOPE Scholarship and the lifelong running tax credit [Lifetime Learning Credit], which we put in—in that one year again, when we couldn’t get money. We had the E-rate, we had direct lending, and we had college work study things like that, but the HOPE Scholarship was a tax credit for the first two years, and it’s lifelong learning after the second year was also a tax credit. All of those were very positive things, I think, for education. I can’t think of a thing that I thought was really important that I couldn’t sit down with Ted Kennedy and say,

What do you think about this?

and he’d say,I’m all for it, go for it.

You know, that was gold.Heininger

And did you have that relationship with all the other members of the Senate and the House of Representatives, that you’d sit down with each of them and they all would agree with you on what you thought?

Riley

Very few, but you know, I did have basically good relationships, especially with the Democrats, but with Republicans too. I had a pretty good relationship with them, and then as everybody is saying now, even [John] McCain, things like education don’t work unless you do have everybody working together. And that’s the truth. Of course, Barack Obama has said that in very eloquent terms. But that’s an interesting little battle going on. I think education will get more into it as it gets on down the line a little bit. I’ve been kind of disappointed that it has not been a major factor like healthcare.

Heininger

No, it really hasn’t and it should be. Is there anything else you want to discuss?

Riley

We’d put groups together. He was very good at that. The one thing I remember, when we had a school construction, we were trying to get some effort out there to help with school construction movement, and he and his staff put together different organizations, like the architects and whatever, to come together, and then we would call a meeting. But he’s into that, that’s important to him, to get different factions to come together and meet and work out something. Again, that’s his idea of moving forward and not just stand around and screaming and hollering about something, but getting all the people in the room together and work out something.

Heininger

Did you ever travel to Massachusetts with him?

Riley

I traveled to Massachusetts a number of times. By the way, I represented President Clinton at Rose’s [Kennedy] funeral. I was that close to the Kennedys. I would be surprised if that didn’t come from Ted Kennedy, because President Clinton was overseas somewhere or something, he couldn’t possibly come, and then President Clinton called me up and said,

I want you to represent me.

And so I went up there and we were with the whole family the whole time, [Arnold] Schwarzenegger and the whole crowd. That’s pretty close, isn’t it? Ted Kennedy gave this beautiful eulogy. Rose was a critical member of that family. My father having supported Jack, and you know we were all Kennedy people. Everybody who knows me and knows my father knows that I’m a Kennedy person. I was very honored to represent the President at Rose’s funeral. It was a beautiful funeral.I went to a number of school events in Massachusetts and he would be there and we could talk for hours—flying with him, talking to him for hours. He’s the best company in the world. I wrote a long letter. I was so touched by his illness, and you see Vicki [Reggie Kennedy] just sent that letter to me. She’s been a real blessing for him.

Heininger

She’s wonderful.

Riley

Yes. Look at that lovely little note she put on the bottom.

Heininger

And you know, the most important thing I think for him right now, is that he gets to sail on his sailboat.

Riley

Yes.

Heininger

He loves that boat.

Riley

He loves that boat. But I hope he’s getting along all right. Have you heard anything else about that? I was there when he spoke at the convention. I didn’t get to speak to him, but he did a grand job, got the old fire going, but I’m just worried to death and everybody is so gloomy about the condition.

All right, let’s get you on your airplane. I can’t think of anything else here.

Heininger

This has been very useful. Thank you very much.