Transcript

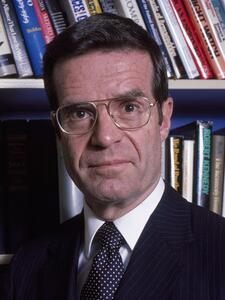

Young

This is a follow-up interview with Ted Sorensen on the 7th of December. I just asked a question about events after the accident at Chappaquiddick, which happened in July 1969, and the time that—

Sorensen

July 19th?

Young

July 19th.

Sorensen

And the speech was one week later.

Young

July 26. And the funeral was the 22nd, and the hearing—

Sorensen

Wait a minute. Whose funeral?

Young

Mary Jo Kopechne.

Sorensen

It was four days before the speech?

Young

Yes.

Sorensen

Oh, I didn’t know that, either.

Young

And the speech was given the day after. There was the hearing, or the arraignment.

Sorensen

Inquest, yes.

Young

And he then entered a plea of guilty to leaving the scene of an accident. Adam Clymer, and many others, in pieces and bits, talk about the people who were there at the house or in Hyannis Port, gathering, and about the construction of his address to the people of Massachusetts on the 26th, and talking about events at the house. At some point you were there.

Sorensen

Yes.

Young

And you were involved in the discussions about the speech.

Sorensen

Yes.

Young

I don’t know who else was there.

Sorensen

I can remember Steve Smith, Milton Gwirtzman. I seem, for some reason, to think Bob McNamara might have been there.

Young

He was there.

Sorensen

I believe that [John] Varick—is that his name?—Tunney was there.

Young

I didn’t know.

Sorensen

Well, his friend. He was very good friends with him.

Young

I know.

Sorensen

I have a feeling he was there. Of course Burke Marshall was there.

Young

Burke Marshall was there. Dick Goodwin.

Sorensen

That I don’t know.

Young

Yes. He came early, I think.

Sorensen

That’s funny. I didn’t remember that.

Young

I think he was there on the 19th, or came on the 19th. Burke Marshall.

Sorensen

Did he stay, Dick?

Young

I don’t know.

Sorensen

Because I came late. As I was starting to say, Steve Smith called me, and I’m quite sure the group had been gathered there, in Hyannis Port, in I think the family house,

the big house,

as they called it, and Steve asked if I would come up. I’m quite sure everybody had been there for quite a while by the time I got there.Young

When it happened, Steve Smith was in Spain.

Sorensen

Oh, really?

Young

And so at some time he was called back. I don’t know when he actually arrived. I don’t know when anybody arrived, but of course his mother was there in the house.

Sorensen

I have no doubt of that, but I have no recollection of it either.

Young

And his father was basically dying, I think then. His father died a few months later, in November.

Sorensen

Oh, is that so? No, that can’t be.

Young

Yes, he died.

Sorensen

Well it’s ’69, it could be. I had seen the father in ’68 with Bobby [Kennedy], but you’re right.

Young

He died in November of ’69. That was a few months after Chappaquiddick.

Sorensen

Tough year.

Young

So whatever you can—

Sorensen

Joey Gargan might have been there.

Young

Joey was there. Joey had been there for the races, actually. He had been there with the races and had been with him off and on, with the reunion of Bobby’s boiler room. Joe Gargan had been there. I think Charlie Tretter had been there.

Sorensen

I remember that name, but I don’t remember him at all.

Young

I think he just happened to be up there for the races. Ted went to the races first, the Edgartown Sail, and then went over to Chappaquiddick for the get-together.

Sorensen

A friend of his, a character from Tennessee, who later ran for Governor, was he there?

Young

I don’t know the name.

Sorensen

Oh, yes you do. John [Jay Hooker]—he ran for Governor of Tennessee, a very southern type. He was one of the inner circle of chums. I don’t know whether [John] Culver was there or not.

Young

I don’t believe he was.

Sorensen

Anyway, that’s all I remember about people present.

Young

OK. What about deciding what to say or deciding—

Sorensen

Again, it’s a very blurred memory. Part of the time, Teddy was in bed. It was rather awkward talking to him about what had happened and what should be said. Milton Gwirtzman and I had a lot to do with that speech. I can’t remember Dick Goodwin, but he might have.

Young

Dave Burke was there too.

Sorensen

Ah, of course he would have been there. In fact, he might be the best witness you could get.

Young

I am going to talk to him.

Sorensen

His memory is sharp, and he’s young and he cares. Burke Marshall probably had some input on that speech. The speech had both legal and political implications and consequences, and so it had to be approached with the greatest of care. At one point I called my senior partner, Arthur Lyman, one of the best lawyers in my law firm here. I don’t remember what specific question that I put to him, a little bit about what the consequences would be of a speech before the formal hearing.

I was a very reluctant participant, I’ll tell you that. I didn’t want to be there, but I thought, as a lawyer, when somebody is in need and asks for some advice that is at least quasi-legal advice, I felt I had some duty to offer that advice. At the time, July ’69, I was thinking about the possibility of running for office myself. I obviously felt very sorry for Ted and wanted to help, but that was not a great place to be for anybody who had a future.

Young

He had been diagnosed with a mild concussion after the accident.

Sorensen

Yes, and he was wearing—if I may say so—quite ostentatiously, a huge bandage around his head, possibly because he needed it and his doctors insisted on it, but possibly to gain some sympathy and remind people that he had been a victim in that crash also. I don’t know. I shouldn’t say, and I don’t say it maliciously. Go ahead. Maybe a specific question will bring on my memories.

Young

You said he was in bed some of the time.

Sorensen

Yes. I have a distinct recollection of standing in his bedroom, talking with him, and asking him a couple questions.

Young

I think one thing I’d like to know is what part was he taking, as far as you could tell, in the actual content and idea of the speech? Was it his idea? Was it Steve’s idea or everybody’s idea, a consensus that he had to make a public statement, and he had to make one soon?

Sorensen

I think that was a consensus view, and I think he agreed with that. Obviously, he participated some in what had to be said.

Young

Very little has been written about this.

Sorensen

One of the best things I ever saw, which gave me some information about the aftermath, was written by the old guy who ran the Martha’s Vineyard Gazette, Henry Beetle Hough.

Young

I don’t know about that.

Sorensen

Well, you know the name?

Young

Yes.

Sorensen

Years later, someone made a speech or wrote an editorial or something, in the Times, charging Teddy with this and that, and Henry Beetle Hough wrote either a letter to the editor or an op-ed piece, saying,

No, that wasn’t it at all.

It was, I thought, quite a good exposition, in the fact that whatever errors he may have made, that Teddy did go to the authorities, he did plead guilty, he did acknowledge responsibility. He was certainly remorseful, and so on and so on. I just remember being struck at the time, that it was a good—he put perspective to the whole thing.Young

He did and does acknowledge full responsibility.

Sorensen

And in the speech he did. I had something to do with that being in the speech.

Young

Adam Clymer says of this gathering and the preparation of the speech that Kennedy was in and out of it, not really doing much about it or really fully participating in it. I don’t know whether that means he was in something of a state of shock or—

Sorensen

I think he was, frankly, in something of a state of shock, or if not shock, post-shock trauma.

Young

Who told his parents?

Sorensen

I have no idea. I don’t know whether his father was in the condition to understand what he was being told in those days.

Young

I’ve heard that he could understand it, but he couldn’t articulate anything.

Sorensen

Oh he certainly couldn’t participate. As I say, I had lunch with him and Bobby the summer before, when Bobby’s campaign for President was underway, and the Ambassador couldn’t speak at all.

Young

That’s right. He couldn’t articulate anything. I have no way of knowing. Clymer also mentioned that there was something in the speech about his saying—not in the speech but in the speechwriting, the idea that he would state he would not ever run for President again. Clymer writes this.

Sorensen

He said that it was in the draft?

Young

Somewhere in the discussions or in the drafts. He’s not specific about it. And he further says that Eunice [Kennedy Shriver] said you can’t say that, that was a no.

Sorensen

Oh, Eunice was there?

Young

Well, all I have to go on are these fragmentary secondhand accounts, and I’m trying to understand what was going on while he was in this state, during that one week.

Sorensen

I’m sorry. I can’t shed any light on that. It sounds like the kind of thing I might have said to him,

Do you think we should put this in the speech?

Just to reduce some of the list of people out to turn to the knife with this. But I don’t know whether I did, so I have no recollection of that.Young

Do you suppose Steve Smith summoned all those people there?

Sorensen

He certainly was the one who summoned me.

Young

You. But McNamara?

Sorensen

That seems unlikely. I think McNamara, just as a loyal friend of the family. He had been very close to Bobby, and Bobby was gone, and Jack, and they were both gone, and maybe McNamara felt somehow he could help and went on his own. I don’t know. But I’m right, he was there, right?

Young

Yes, he was. I don’t know whether he had thoughts about the speech or didn’t. I really don’t know what was going on at that house during this week.

Sorensen

I don’t recall any session in which Milton or I tried out the speech on everybody there. I don’t think there was any such session. We would have naturally shown it to Burke Marshall, and probably to Steve, and obviously to the Senator, and very probably to Dave Burke. I just don’t know whether any of the others there saw it before it was given.

Young

Clymer also says in his book that there was a difference of opinion within the group— whoever was in the group—about the type of statement he ought to make and what he ought to say. Clymer represents that there were some people—I think he called them younger staff; I don’t know who these are—who felt that he ought to make a simple statement of contrition and let it go at that, and not a full-blown talk to the nation, and others felt he should say that.

Sorensen

Which younger staff were there?

Young

I do not know. It’s a mystery to me.

Sorensen

Were any of Bobby’s old staff there? I don't think so. Adam Walinsky?

Young

I don’t know of any.

Sorensen

Peter Edelman, those people?

Young

Peter was not there.

Sorensen

I didn’t think so.

Young

It was Arthur Schlesinger, did he come up?

Sorensen

I’m pretty sure he was not there. I would have remembered if he were. But enough of these people have written their own books that it should be easy to find out.

Young

But it’s not a subject many people talk about. I got interested in it, not from the standpoint—

Sorensen

I got a certain amount of flak for having been there, and maybe for my role in the speech, from some of the people who had been close to Bobby, the liberals, and the younger folks. I was a little surprised at that. I’m not quite sure why that was true. I don’t know if any of them—Goodwin, Walinsky, Edelman, they all wrote books. Did any of them mention this in their book?

Young

No. You get fragments. Since this was a rather extraordinary kind of occurrence, I just think it’s important historically to try to get as much recollection as you can on the record.

Sorensen

I think it would be a very valuable contribution to history if you could do that.

Young

Frankly, I did not ask him: What were you doing afterwards? Because he was, in my interviews with him, talking about other things, not about who was doing what, and that was the most important thing for him to talk about. I did ask if he took the lead in the talk, and he didn’t seem to know what to say in response to that.

Sorensen

I don’t know. What should I say? I don’t really remember. It would not be consistent with my vague impressions that remain to say that he took the lead by himself. He may very well have joined with Steve in guiding the discussion, but that’s not the same as taking the lead.

Young

No. I’ve even wondered in my mind as to whether he was even fully aware of what was going on at that time. I just don’t know.

Sorensen

I agree with that, at least during the time he was bedridden. I don’t have any recollection of how much of the time that was. I don’t even recollect how long I was there. I wasn’t there for a week, I’m sure of that.

Young

They went down to—the funeral that he went down to was on the 22nd.

Sorensen

I don’t have any recollection of that. I think maybe I had come back before that.

Young

I think Bill vanden Heuvel had gone to see the family, had been asked to go down and be with the woman’s family, Mary Jo’s parents.

Sorensen

Oh, well then, you certainly should interview him.

Young

Yes, I have, but I don’t think he was there at Hyannis Port.

Sorensen

Oh, he didn’t go from Hyannis Port.

Young

I think afterwards he went there, but he wasn’t there immediately after the event.

Sorensen

Are you interviewing Milton Gwirtzman?

Young

Yes, I will interview him.

Sorensen

He’s helping cooperate on the project.

Young

He’s helping get documents. He’s doing the briefing for the Senator, and he and I worked together in gathering materials and posing questions.

Sorensen

I would interview him and Dave Burke, and you’ll get a lot, a lot more than I can remember.

Young

Dave is on the advisory committee for the Kennedy project.

Sorensen

I didn’t know there was an advisory committee. Thanks a lot for not appointing me.

Young

Well, I—

Sorensen

No, I’m serious. I’m not saying that sarcastically.

Young

In the formula for the advisory committee, the Senator was given—this is the arrangement that was agreed upon—two representatives on the committee, on the Advisory Board, which I appoint, but those were his appointees. I wanted to appoint mostly independent academicians or scholars, historians.

Sorensen

Did all this begin after Burke died?

Young

Who died?

Sorensen

Burke Marshall’s dead.

Young

It was about two years ago, a year and a half. I’m trying to remember the exact date, but Lee Fentress and Dave Burke were the people he chose to be his representatives.

Sorensen

Lee Fentress and Dave Burke? That’s interesting.

Young

You know Bob Dallek, of course. Bob Dallek is on the board. They serve a two- or three-year term, and then we can rotate it. Bob Caro.

Sorensen

He’s a very thorough historian.

Young

He’s on the board. We wanted independent, outside advisors, to make sure that this was not a Kennedy operation.

Sorensen

That’s the way it should be.

Young

And he was very specific that it should not be that and not be seen as that.

Sorensen

He, Teddy.

Young

He, Teddy.

Sorensen

That’s good. That’s the way it should be.

Young

And Vicki [Reggie Kennedy] the same, obviously.

Sorensen

I don’t think Joan [Bennett Kennedy] was there, now that I think about it.

Young

There’s no record of her being there at all.

Sorensen

Or any of his children.

Young

No.

Sorensen

They were pretty young at the time.

Young

Well, that’s as far as we can go with that, I suppose, unless you have some other thoughts just on Chappaquiddick. I shouldn’t say Chappaquiddick. I’m thinking the decade of the ’60s. How it began and how it ended.

Sorensen

Quite a decade.

Young

Oh it was. I don’t know how anybody could live through that as he did and keep going.

Sorensen

I don’t know what I can add that isn’t well known. The ’60s began with JFK’s [John F. Kennedy] election, in which Ted played an important campaign role. It moved then to Ted’s election to the Senate in ’62. It moved then to Jack’s death in ’63. Bob’s election to the Senate.

Young

A plane crash in ’64.

Sorensen

A plane crash in ’64 and Bob’s election in ’64.

Young

Then they were there in the Senate together for a brief time.

Sorensen

Yes, exactly, that brief period. And Bob running for President in ’68 and being killed in ’68.

Young

Chappaquiddick in ’69.

Sorensen

What a decade.

Young

The father died in ’69. That was quite extraordinary. Let me ask you about something else. I noticed in reading your transcript that you said at one point you were calling him Teddy, and then later it was going to become Ted or Senator.

Sorensen

You mean in the transcript.

Young

In the transcript you said that, which you didn’t do, I don’t think. You didn’t change it consistently, but that’s not my question.

Sorensen

For the years that I remember best and that mattered most, he was Teddy. Jack called him Teddy and Jackie [Jacqueline Kennedy] called him Teddy, and even Bobby called—who didn’t like being called Bobby all that much—

Young

Here it is.

Sorensen

Do you see it?

Young

Do you want it?

Sorensen

Yes, please.

Sorensen

If he were sitting here today, of course I would call him Senator, but if I didn’t think he would be bothered by it, or if I were assured he would not be bothered by it, I would probably still call him Teddy.

Young

People do.

Sorensen

And Jean [Kennedy Smith] still calls him Teddy.

Young

My question was going to be, at what point you yourself began to—did he become a Senator to you, rather than just Teddy, or did he become Ted or a Senator?

Sorensen

That’s a very good question. I suppose that change did not take place with his election. I don’t remember how much I saw of him after JFK’s death. I don’t have any distinct memories. I remember going to his office once, but I can’t remember what about. I remember that he organized a book on the Antiballistic Missile Treaty, to which I contributed a chapter. Also, I may have served as the lawyer for that book in terms of publishing contract and so on. He may have talked to me about doing another book. Did he do another book around that time?

Young

I can’t tell you if he did another book.

Sorensen

After Bobby?

Young

Besides that, but I don’t know what it was.

Sorensen

Kind of a collection of verses and sayings that he liked.

Young

Words Jack loved.

Sorensen

Yes. I think he consulted me about that.

Young

He put together that.

Sorensen

What year was that?

Young

I do not know.

Sorensen

Then, of course, there was the possibility of his running for President in 1968. I remember at least one meeting on that, and staying at his home in Virginia on the way to the Chicago convention in ’68. I was in touch with Steve about that. I’ve written a little bit about that. Then, in ’70, I ran for the Senate here. Steve was very helpful. I don’t know that Teddy was involved very much. He served a year or two as the Senate Whip. What years were those?

Young

That was—I’ll get it in a moment.

Sorensen

It might even have been ’69-’70.

Young

I think it was ’69. When he came back to the Senate—Mike Mansfield was, of course, Majority Leader then—he kept it for one term and then lost it to Bob Byrd.

Sorensen

Yes, and made a funny speech at Gridiron or somewhere else, saying that he didn’t understand how he could lose it, that his staff had assured him that he had the votes of Senator so and so, so and so, and Sorensen, which of course, I wasn’t, because I wasn’t elected.

Young

Byrd had a better vote count.

Sorensen

Yes, he did. Not surprising.

Young

Just as an observer, whether you had any—regardless of the contacts you had with him, just to the extent that you were a Kennedy watcher, or somebody who could observe, you were active in politics yourself—did you see, was there a point at which you began to think of him differently from the way he was thought about as Teddy? You also refer to the great distance, not only in age but in the early years, the great distance between—Bobby and Jack were close, you said, and Teddy was a great distance from them.

Sorensen

Yes, in more ways than one. When you’re small, age differences matter much more than they do later on.

Young

But thinking of a time, if you just look at his career, following what’s he doing now, over the years, did you see a change in him?

Sorensen

Then of course came his second try for the Presidency in 1980. I was again involved in those meetings, debating whether to run, what the strategy should be, and so on, and there were quite a few of those. Dave Burke and I collaborated on some strategy memos and advice.

Young

Did you think that was a good idea, for him to run?

Sorensen

No. I thought that it was not. I thought that Chappaquiddick still hung in the air, and that running against an incumbent Democrat, as I had learned with Bobby, is always a challenge. It’s difficult. There might be better years to wait for. Steve and I, I believe agreed that ’80 was not the best year, until we went down to his Virginia home for a meeting one night, and some of his other advisers were there already. I’ve forgotten who. He said,

Well, I’ve decided to run.

Oh. That’s what we thought we’d come down there to discuss, and we said,All right. If that’s your decision, great. We’ll do what we can to help.

I tried to help him a little bit in New York and so on, but I wasn’t asked really to help on message or strategy or anything of that sort, including his not very helpful interview by Roger Mudd. I helped sell some tickets for a big fundraising dinner he had here, and then he asked me to represent him on the platform committee, with the convention. The platform committee actually met the week or two before the convention, in Washington. I don’t think there was anybody else in the race seriously, was there, besides him and [Jimmy] Carter?

Young

No.

Sorensen

So we had the more liberal banner, and I did my best, although I think Carter had control of the votes in the committee and in the convention. Then, I believe I attended the convention in—where was it, here? I think so—1980?

Young

I’m blanking. Yes, it was.

Sorensen

I attended that convention and at least on the occasion when he delivered his very wonderful speech about the dream that will never die—so obviously somewhere between 1970 and 1980 he became the Senator and not just Teddy.

Young

Why would he want to run in 1980 and having decided and started in with it, why would he want to persist, even after it was clear that Carter had the votes in the convention? Do you have any thoughts on that subject?

Sorensen

Well, when you say persist, he’s a Kennedy. Kennedys are fighters in politics, they don’t give up. And he was, after all, seeking personal vindication, having let down his supporters and his family and himself in the combination of Chappaquiddick and not being able to prevail in earlier Presidential nominations. So I understand him doing everything he could to wrest one last opportunity to show what he had.

The support for Carter was not that deep in 1980, and I think Ted may very well have thought that he could, if it were managed right in terms of ballots, still get that nomination in a fashion dramatic enough to take him all the way to the election, although nobody knew then how tough Ronald Reagan would be as an opponent.

Young

Was it kind of assumed, as you remember it, that Reagan was not a strong prospect for being elected? He seemed so far to the right, and his history had been so far to the right. Was the thinking in Democratic circles that the country won’t elect somebody like this?

Sorensen

I think that is probably true. I’m told that Carter was astonished. I still remember—my wife and I were living right here, and our voting was across the street. We were walking out that morning on election day, going to vote, and in through the door came a very good friend of ours, married to a very good liberal, Democratic friend, activist Democratic friend, and I said to her,

Well, I know how you voted. And she shook her head and said, No, meaning Carter versus Reagan. She shook her head and said, No, I just thought— This lady had never been involved, to the best of my mind, in business, but she said, If I were on the Board of Directors, would I reappoint a President who had this record? I couldn’t vote for him. And I said to myself,

Oh boy. If Carter doesn’t have her vote, he’s getting no votes at all.

Young

He apparently didn’t know it until the last—didn’t recognize the handwriting on the wall. But then of course the hostage crisis.

Sorensen

The hostage crisis and inflation, and he couldn’t do anything about either one of them, and they reinforced a sense in the country that he was ineffective.

Young

But when the hostage crisis came on—

Sorensen

I even wrote an op-ed piece in the Times, which I’m sure you can dig up, that fall. I think I wrote an op-ed piece—which ends with an injunction to Carter,

Pray, sir, lead—

All I remember from it is that last line. I know I gave an academic lecture that fall also in which I was quite critical of Carter. I think it was the fall after Teddy was well out of it, but it’s possible that, now that I think about it, that speech came in the winter before, when Teddy was still thinking about running. In any event, I think Carter was a disappointment to many people. He’s been a great ex-President. He fulfilled his campaign promise, not to be involved with Washington.Young

You have to stop running against Washington.

Sorensen

After you’re elected you do.

Young

Yes. But of course, when the hostage crisis came on, that made it very difficult for Ted, because suddenly the President was concentrating on a foreign crisis, and also that dominated the news. Isn’t that right?

Sorensen

It surely did.

Young

And Ted’s running against him was basically on domestic matters.

Sorensen

A little quirk of history that is not important, because nothing happened, nothing came of it, but it’s going to be mentioned in my book. One of these mysterious, self-appointed intermediaries, saying he could solve the crisis. Someone decided that Senator Kennedy was the one person to whom the Iranians would release at least some, if not all, of the hostages to. He called Teddy or Teddy’s office about working something out, and Teddy sent him to see me.

He came to me in the dark of one night, and I have no idea whether his credentials were genuine. I thought, Well, of course if Ted Kennedy could be taken by this gentleman over to Tehran and come back with the hostages, that might be a tremendous breakthrough for his Presidential campaign. But if he came back with only a few of them, which was what this gentleman was offering, it had to look as though he was agreeing with the Ayatollah about this or that. I thought that was a highly dubious road for Ted to go down, and in any event, whether Ted ever saw him and talked with him again or not—I reported to Ted on the conversation and my doubts, so he may have just said,

Forget the whole thing.

I never saw the man again and I don’t think anything ever came of it. That’s one of those potential turning points in history that did not occur.

Young

Sometimes intermediaries appear and vanish.

Sorensen

Yes. There was a whole program about them at one point, and this man wasn’t involved in it. But there were a couple of other intermediaries who had Hamilton Jordan, at the White House, convinced that he should fly over there, and it all vanished.

Young

He went over to Europe wearing a wig.

Sorensen

Yes. Pierre Salinger was involved somehow.

Young

Of course they never knew who was bona fide and who wasn’t.

Sorensen

Exactly. After that, I’m trying to think if there were any special things that Teddy and I did together, aside from a few memorial services and funerals. Offhand, I can’t remember any, although I still consider him my friend and I think he still considers me his friend, and once in a great while he’ll ask me my advice on this or that.

Interestingly enough, one nice little anecdote—I should try to put this in my book. I’d forgotten all about this. He was going to hire a young man for the Judiciary Committee staff. At the time, Ted was either Chairman or the ranking member. And he said,

Could you interview him for me?

I was on the road all the time, in my international travels, and finally we agreed that this young man and I would share a taxi from the airport into Manhattan, and that would be the interview. Interestingly enough, that was Stephen Breyer.Young

You’re right, get it in the book, and the book has to come out before this. You don’t want to scoop yourself on this. I hadn’t known who interviewed Breyer. Now I know it was in a taxi. That must be another historical worth. Well, I’ve taken a lot of your time.

Sorensen

As always, I’ve enjoyed it, and you always do a thorough job.

Young

I do what I can. I really do enjoy being on the project, because it’s like I’m learning history from those who made it. That’s very special.

Sorensen

Not many historians do that.

Young

That’s right. So, thank you.

Sorensen

You would have been interested at that conference at the Miller Center, on consuls to the President.

Young

Yes.

Sorensen

It didn’t involve Teddy one way or the other.

Young

It didn’t. I had a little bit to do with putting that thing together, actually.

Sorensen

You see, I find myself incapable of stopping calling him Teddy. That’s just what automatically comes from my brain to my mouth.

Young

Well, I’ll tell you, I don’t call him that. I didn’t know him way back, which is another virtue of this project. I’m outside, so I don’t bring in any of—

Sorensen

Yes. Although it’s unfortunate that so many histories of JFK have been written by people so far outside. They didn’t know him well enough to understand him, and they write a lot of nonsense as a result.

Young

Right, right. Well, he didn’t live long enough to have an oral history like this, where he can himself talk.

Sorensen

That is certainly true.

Young

His own voice.

Sorensen

He did have tapes.

Young

He did indeed. Well anyway, we’ll close the interview.

Sorensen

Did I tell you? It’s in my book—during the Cuban missile crisis—I think maybe we did this last time—I only accepted two or three phone calls, and one of them was from Teddy. October 22nd, when the President made his speech, and he said,

Can I give my standard speech on Cuba?

I said,No, wait until you hear the speech.

Young

And he did what you said.

Sorensen

I assume so. Then, after it ended, he was about to go on Meet the Press, and the President sent me up to give him a little briefing so he didn’t say the wrong thing on Meet the Press, because whatever the President’s brother said would have been interpreted around the world as being the official position.

Young

Exactly. There must have been a bit of nervousness about setting him loose on the campaign trail. [laughter]

Sorensen

Yes, I think there was.

Young

Especially because he wasn’t up there with Jack and Bobby, but he was a different kind of a person in some ways.

Sorensen

Well that’s why the President sent Bobby and me up to give him a little briefing before his debate.

Young

OK. We’ll end it.