Transcript

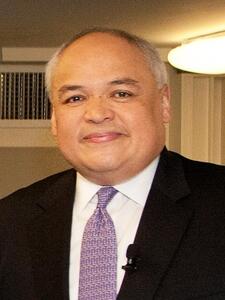

Heininger

This is an interview with Thurgood Marshall, Jr. Tell me about when you first met Ted Kennedy. What were your initial impressions of him?

Marshall

I mentioned that I wrote down notes. I don’t know the answer, and that’s partly because the Senator and his family were so important to the history of my family. I have early recollections. But I’m not sure, to tell you the truth. The first recollections I have of interacting with him are from the 1970s.

Heininger

That’s all right.

Marshall

That was in connection with judicial conferences that I attended with my parents, when my father was a Justice on the Supreme Court and would attend judicial conferences. Me, being the lawyer wanna-be, would go along to try to pick up things. Actually Kenneth Feinberg, who was on his staff, was often part of those conferences, and the Senator would show up and speak. Kenneth Feinberg was working for the Senator at the time. He was either working for him or was working as a facilitator with the federal judges.

Senator Kennedy was well on my radar screen, not only because of his family’s involvement with my family, but as a student of political history—and for lack of a better description, a political junkie—I was very interested in the process, particularly the legislative process. Senator Kennedy had been involved in my father’s confirmations when his brother introduced him as my father’s home state Senator to the Judiciary Committee and Senator Kennedy was a member of that committee. When I eventually got to UVA [University of Virginia] to study, it’s a federal depository, so it has, as you know, hearings and transcripts. When I should have been studying one night, I tracked down those transcripts.

Heininger

Really?

Marshall

It was a delight to see some of the Senators who went after my father, but on the other hand, to watch Senator Robert Kennedy and Senator Ted Kennedy dealing with the situation and jousting with both good humor and good effect, turning questions back on other Senators. There was one in particular who was asking questions that were just about as obscure and Byzantine as you can imagine, things like,

Mr. Marshall, could you identify the members of the committee that drafted the first draft of the 14th amendment to the Constitution? This is, after all, a position where you need to understand the Constitution.

He was sitting at the table and acknowledged that he couldn’t identify all of them, and Senator Ted Kennedy leaned over and asked if the Senator asking the question might provide that information, and of course that Senator didn’t have the information either. Little things like that caught my attention, and over the years, I became a huge fan of Kennedy’s. I would have to say that it was at one of those judicial conferences where I first crossed paths with him.Heininger

What were your impressions of him?

Marshall

Not so much the movie star reaction, because by the time I crossed paths with him, he was pretty well substantively established in my head. This wasn’t so much the persona, but also that he was carrying with him all these efforts, these causes. The policy wonk, substantive side of things had a charismatic effect on me. I was pretty mesmerized from afar. Through that period, he was engaged in many issues and battles that caught my attention.

Heininger

When you first came to the Senate, you worked for [Albert] Gore.

Marshall

That’s right.

Heininger

Much of your career has been with the Senator and Vice President Gore. Why did you end up working for Gore?

Marshall

Actually, I ended up going to a law firm, not long after I finished the judicial clerkship, where every one of us who went there as junior lawyers had identified it as a boutique law firm that was formed by a bunch of former Hill staffers and run by Ken Feinberg, a former Kennedy person. To varying degrees, the game plan for each of us was to get that legal training from these talented, young, former Hill people and then get to the Hill.

Heininger

Interesting.

Marshall

Indeed, I’d say 90 percent of them did. This was 1983 to ’85.

Heininger

This was Kaye, Scholer, Fierman, Hays & Handler.

Marshall

That’s right. The rest of my plan, frankly, was to find a freshman Senator, A) because there would be more time, and as you know, the staffs are smaller. That way, I would be able to establish more of a portfolio. Part B of the plan was to find a freshman Senator who had well-placed Presidential aspirations. It was a good class for that plan.

Heininger

It was.

Marshall

Because ’84 was, among others, John Kerry, Paul Simon, and Al Gore. I may be leaving someone out, but eventually, just about everyone from that class ran.

Heininger

Did Gary Hart predate that class?

Marshall

Yes. Al Gore ran for President in ’87/’88. I was the deputy campaign manager, and when we were wrapping up that campaign, we were talking and he said,

We haven’t talked about what you want to do next.

I had gone to the Hill with the thought of working there for a year or two, trying to learn it well, and then coming back downtown to try to apply that knowledge. But I knew that I had not been there long enough to learn what I needed to learn in terms of the areas of my interests. I said,I haven’t given this much thought, but the first thing I’d like to do is see if Senator Kennedy has something on the Labor Committee or the Judiciary Committee.

Senator Gore was puzzled at first because he was a little more moderate ideologically, but he knew that I had volunteered on the Kennedy ’80 campaign, and he knew of my interest, but he asked me why. I explained to him that before I got to the Hill, it was clear to me that there were a few offices where, because of the ability of the Senator, the staff had a reputation of understanding the procedures and processes on Capitol Hill. It seemed to me that Kennedy’s office was one of the places where I could get the full Senate procedural experience in legislation, the legislative process experience that I wanted. Gore said,

Let me know what you find out.

There was an opening in Kennedy’s office. I got incredibly lucky, because those jobs don’t always pop up when you need them to pop up.Heininger

Did Gore facilitate your getting a job with Kennedy?

Marshall

Once I found out that there was an opening, he placed a call.

Heininger

At that point, was the opening for a counsel for the Immigration Subcommittee?

Marshall

Judiciary. Yes, that’s right. Carolyn Osolinik was the chief counsel there. Jeff Blattner, Michael Myers, and Jerry Tinker were there, and Laverne Walker and Annie Rossetti. It was a great place for me to learn the processes as one should, as opposed to the way I started, which was wonderful in terms of learning a Senate office process and the politics of getting elected and staying elected—which, with a freshman Senator who came to office the way Gore did, who was doing town hall meetings every weekend, was a nice one-two combination for me.

Heininger

So you came on as counsel for the Immigration Subcommittee. Who did you work with on that subcommittee?

Marshall

Carolyn Osolinik was the chief counsel. The way the subcommittee was run during that time, Jerry Tinker and Michael Myers were handling all the immigration, refugee-affairs issues and were steeped in those issues. Carolyn was the chief counsel and was involved in those issues, but she also was involved in any Judiciary Committee or Judiciary-related issue. She was chief counsel in every way, in that sense. I handled, among other things, the criminal law, crime, criminal procedure, anti-drug issues and spin-offs of those, as well as issues at the Commerce Committee. I had briefly worked at Commerce before that, so there were telecommunications issues, and in Massachusetts in particular, with the tech corridor. We had a number of those issues that came up.

Jeff Blattner was there. In fact Jeff and I shared a half wall in one of those Dirksen offices up there, little cubbies and things. I inherited a number of the crime issues from Jeff. I was there for, gosh, it must have been about four years. Jeff hung on to some of the criminal justice issues, particularly the constitutional ones, for the first couple of years, including habeas corpus and the death penalty. I eventually I picked those up as Jeff got more involved with Supreme Court nominations and other constitutional law issues.

I think I was subconsciously aware that if I were able to land on a staff like the Kennedy committee staff, not only would I be working for a senior member who was steeped in the process and legislative accomplishments, with a healthy agenda, but I also would be thrown in with some hard-charging, talented people. I was drawn to that. I had dealt with each of those folks on that committee, because I had handled Judiciary Committee issues from afar, and I had seen them in action. That all was a joy. The biggest and most important piece of that for me, in terms of who I worked with, was Carey Parker, who was the dean of all Kennedy staff. I was well aware of the legend.

Heininger

Still there.

Marshall

Yes. I had many wonderful experiences with him, and I can’t say that about anyone else who has used as much ink on my drafts. We all like to think we’re good writers. I will argue with people about changes and edits, and I will swallow hard when someone senior to me does that. I remember thinking initially, I’m sure he’s very good, as everyone says he’s very good, but this could be interesting. I never could find something to take issue with. In fact he made things sing. I knew, because of his judgment and his experience and his smarts, that he would be able to help put anything I worked on or wrote in the Senator’s voice, which is a valuable thing, especially for someone new. I frankly was not prepared for how sharp and quick he is and how special he and the Senator are in so many ways.

I wrote an op-ed, and I’m sorry I didn’t look for it, for the Senator on a gun issue. I did a few of those, as anyone on the staff would be expected to do. The first time I did one, we worked hard on it, we got it done, and I got a little note from Carey that said,

Good job,

and it was attached to a check that had been made out—I think it was the Times—to compensate the Senator for the op-ed, who had then signed it over to Carey, which I thought made all the sense in the world, because for all Carey does, there are ceilings on those Senate salaries. I thought, what a wonderful thing this says about the Senator. But then Carey signed it over to me. I’ll never forget that. I almost wanted to frame it, but being on a Senate salary—Heininger

That’s a great anecdote.

Marshall

I’m not sure I should tell it, but since you had given those—

Heininger

No, that’s a wonderful anecdote of how Kennedy deals with his staff and how his staff operates internally. That’s exactly the kind of thing that makes an oral history special.

Marshall

I hope so. I thought it said wonderful things about both of them. There are so many permutations of that too, in terms of that analysis, because I would bet all that money and more that Carey never told the Senator that he signed it over to me. They’re two very special people, and I don’t think I fully comprehended, until I got in that job, how much I was going to benefit from that exposure.

Heininger

How did Kennedy operate in terms of dealing with his staff and the integration between the personal and the committee staff?

Marshall

That was a seamless process. The lines were clear, particularly on Capitol Hill. That never ceases to amaze me, looking back on it, because it is one of the larger staffs. There was healthy competition but not in a negative way, which also could happen in that kind of environment.

My perspective was as a result of coming from the Gore office, where he had a wonderful group of people, by and large very young, many of whom, as often happened with freshman Senators, had been involved in the campaign in some way and had moved into town. I had a concern that in doing my job, I might be isolated from the Massachusetts piece and might not grasp that. My concern, frankly, was not that I wouldn’t serve him. I knew that anything I could possibly learn about state interests, he would have already known for decades. I didn’t want to shortchange him on what was expected of me.

I quickly realized that I wasn’t going to be running back and forth to the state as much as I did with the Tennessee folks and the Gore office. But the staff understood that. Folks in the Massachusetts office or people in the personal office who handle Massachusetts issues—and for me, that was usually Mary Jeka—were incredible resources. Another interesting thing to me was that I came from a Senate staff where I learned e-mail pretty quickly. We didn’t have computers when I first showed up. We didn’t have TVs. We had the radios, the boxes.

Heininger

Oh, I remember.

Marshall

The TVs came in eventually. While I was in the Gore office, the computers showed up, and we were using e-mail. Gore is a very heavy e-mail user, and was I worried when I realized that. I don’t know why I was surprised—but I was—that there was no computer in Senator Kennedy’s office. I thought, how am I going to do this? I’m sure they have this figured out, but it has to be clumsy. With this many people, it must take longer. But it worked.

It worked like an efficient machine, and I at the time gave credit to Ranny Cooper, who was our chief of staff. I think everybody understood that there was a regular process, and the process seems to still be in place, with the bag and the briefing materials and people scheming not only to get their stuff in the bag in the right place, but to have it look like it might be a little more interesting than the next item in the bag. What made it work when I was there was that Kennedy threw himself into the materials and was remarkably aware of what was coming up on the calendar, short term and long term.

I have since been—I’ll try to remember to make a note of this—dressed down by him in front of a client for being less than prepared on something, and he was right. He’s incredibly gracious when he senses that any of us on staff are downtown and need help or a boost, but he’s also incredibly honest, and it was one of those instances where I should have known, given the way he runs the process there. You can’t suddenly load him up with a new, complicated issue to take on when he already has a full plate, much fuller than most. That’s a very long-winded answer to who I worked with a lot and how the process worked.

I found that the bulk of my work with him was driven by a few things. One, the beginning-of-session strategy that we would all put together, and to the extent that there was competition in the office, that was certainly where it occurred. We each had our portfolio.

Heininger

In that planning process?

Marshall

Yes. We each had our portfolio, but Carolyn and Jerry wanted to make sure that the Judiciary Committee agenda had as much of his time, and provided as many projects of value, as was fair and appropriate, that we didn’t waste his time if we brought him over there. But within that, I think we tried to make sure that we had a healthy piece of that time. Anyone watching the process knew that the best way to have a good session was to get in early on that part of the process. But things pop up at all times, and that’s a wonderful aspect of the way that office has been run, that there is, despite the fact that he has an incredibly full plate and thrives on it, obviously, there’s plenty of flexibility to jump on issues as they arise, which I think any good Senate office is able to do quickly. In the shorter term, getting in the bag was a foolproof way of getting a read from him.

Heininger

How did somebody go about getting something into the bag?

Marshall

That’s remarkably easy. The trick is to not abuse getting something in the bag. Just put a memo in there or briefing material or

Here’s an article in this issue area, or related to the issue we have been working on, that either ought to be addressed or is supportive of what we’re trying to do.

Many of the bag obligations were driven by his calendar. If we had hearings coming up, he wanted to know what the plan was for the hearing, and not just who was coming to testify and what they were going to say. We were expected to work it in the committee and to find out who was trying to establish what points, to determine whether it was headed in the right direction, whether there were opportunities for us, obligations to protect, issues that might arise, or opportunities in the sense that we might be able to move some of his initiatives. In that office, it was not unusual for projects to come from other committees, through one committee or another, or on the floor. The senior Senators, or the more effective Senators procedurally, know that there’s always more than one way to skin a cat.Heininger

Yes.

Marshall

As you mentioned on the Marty Gold tapes, looking for a recess was not just an opportunity for people like me when I was first getting in there to get caught up. There were always efforts in the office to get more steeped in procedures, and CRS [Congressional Research Service] was wonderful about that. Of all the things I miss, that’s—although a lot of that is available online now.

Heininger

Yes, finally.

Marshall

I have to restrain myself sometimes, because it’s such a tempting place to delve into just to get my jollies on issues.

Heininger

Who controlled the bag? Who put it together? Was that the chief of staff, or was that Carey?

Marshall

That was the chief of staff’s office. Ranny made sure that anything that needed to be in the bag was in there and was well done. More often than I would like to admit, I got to the bag with time to spare but not with enough time that if Ranny spotted something, I’d have time to fix it. During my time, a succession of people, including Lisa Young, sat with Ranny, right outside the Senator’s office, and they handled the bag.

Heininger

The bag actually didn’t go through Carey?

Marshall

No. I don’t know that there were any hardcore procedures, but I think anyone who didn’t copy Carey on anything that went to the boss was missing an opportunity and risking serious problem. The weekend bag was a great place to try to seed some ideas for later, but anything that was coming up—a hearing, briefing books, questions, commentary or remarks, floor stuff—needed to be in there well in advance.

We’d get comments back. Of the many things I was not prepared for and I thought I understood—I always think I understand everything before I do—was the degree to which he—either because of his prior work or because of the many layers and circles in which he travels, combined with his retention—had questions that were well informed. I’m not sure how to articulate it, but he has a wonderful combination of memory capacity and travels, so to speak. He has a knowledge base that is intimidating until you figure out how to take advantage of it and benefit from it. Then it’s a wonderful resource.

Eventually you get a better sense of who he’s been talking to or what he’s been reading. Some of that comes from, frankly, the issue dinners, which are wonderful. I’ve been blessed with bosses who believe in personal growth, and as busy as they are, they carve out the time. He can call in experts and just let them go, and he can quiz them and push them for more information. He has a circle of acquaintances and former staff. It’s just amazing.

Heininger

The Kennedy network.

Marshall

Yes, and he always needs somebody like Ranny, Carey, or in my case, Carolyn around. When he says,

Did you talk to so and so?

I quickly learned that on a lot of my issues he meant,Did you talk to Stephen [Breyer]?

These were crime issues, antitrust issues, and Sentencing Commission issues. He created the Sentencing Commission, and that was one of my areas as well.Did you talk to Steve?

was going to be the question.Heininger

Who’s Steve?

Marshall

Exactly.

Heininger

You figured out quickly who Steve was.

Marshall

Right, and after that, I didn’t ever want to say that I hadn’t talked to Steve. Steve was Stephen Breyer, which to me at the time meant Judge Breyer. I’ve been fortunate in a couple of jobs where, because of where I was calling from, people would take the call. Judge Breyer never was unavailable and always had interesting, useful things to say. I had no doubt, after certain experiences, not just with the Stephen issue, that if there was any doubt in the Senator’s mind about whether I had pushed for every possible answer and alternative, that he would pick up the phone and do it. It’s a wonderful way to do those jobs. I had been in the Gore office for the longest time, and there were people I would have loved to have called, but I was limited in my ability to get access.

Heininger

How would you compare how Gore ran things versus how Kennedy has run things? You then go back and work again with Gore, so there’s not just the Senate experience.

Marshall

In some ways, they were very similar, because the Vice President was and is methodical in terms of periodically taking stock of the long-term and short-term plans. This notion that you do the planning—you may not stick with it, as so many people do not, but if you have the plan in mind and people are aware of it and they are familiar with it—you don’t want to keep it a secret, but there’s an effort to nail that down, and you can proceed from there.

Also, the notion of personal growth and the importance of carving out time for personal growth in terms of reaching out to authors, policymakers, or opinion leaders, and having that set of resources there, they both did that in ways that I found inspiring. I feel as if I get to different stages in life and I know from watching them how important this is, but I think to myself, gee, I’m too busy. Well, they are, by definition, much busier, but they still do it. A lot of people succumb to those time demands and constraints, but seeing them do this has been very valuable to me. There are similarities and parallels there. The ability to take from those lessons, whether they’re going from a reading list that someone has produced for them or from topics that come up at a dinner or a retreat, it comes back in different and interesting ways.

I don’t think I ever, with either of them, had a routine briefing on something. I probably did. But it wasn’t like a Senator [Robert] Byrd historical tutorial in the sense of it being a long thing, but there were little snippets of—well, there’s a parallel to—maybe I will think of some examples. But both Vice President Gore and Senator Kennedy would regularly take something I had worked on and had been pretty pleased with and had gotten plenty of help on, and they would then take it, look it over, and come back with new and different perspectives—not so much pointing out something that I or people who were helping me had missed, but they had an ability to see links that others don’t.

Heininger

That’s a skill.

Marshall

It is.

Heininger

To be able to make those links and to go beyond, it’s part of being able to think outside the box, while drawing on a knowledge base that they have that isn’t available to most people. That’s an astute observation about them.

Marshall

Yes, and it can be intimidating for a staffer, but once you get to the point where you say to yourself,

It’s going to happen,

you’re okay. There are memory banks and knowledge bases that they have, because of the circles that people in those positions are able to travel in, that most people don’t have. It’s the ability of certain individuals who are entrusted with those kinds of positions. It’s the ability of some of them to take it that next step and to see the links that is a special talent. To be able to see it is special.It happens on little things too. More than once, like a lot of staffers, I gave the Senator something for a hearing or a meeting, something I threw myself into, only to find that he took it and made it better. Some of that is just straight-up experience, but he’s always been good on his feet, even though there are times, like the infamous Roger Mudd interview, where he was good on his feet but less than articulate about it.

I learned from the press secretary at the time, Paul Donovan, who was there. Paul called one morning and said,

A couple of reporters caught the Senator outside of a hearing and asked him about—

It was an issue I was working on, and I can’t recall what it was. I think I know what it was, but I’m not going to hazard a guess. I was concerned because we were in a delicate negotiation process, and Kennedy said,Well,

and he ran through something that was reminiscent of the Roger Mudd interview. As they were walking away, Paul said that the Senator turned to him and said,I don’t think there’s anything in there you can use, do you?

Heininger

A knack of dealing with the press.

Marshall

Right. I don’t think you’d want to let that out, on the one hand, but I think it’s a willingness to have a member of the press draw a conclusion that you can’t express the thought when in fact you’re giving them the impression that you’re trying to answer without walking away. It was a nice lesson.

Heininger

It’s quite a skill to be able to say nothing.

Marshall

Right, while appearing to try.

Heininger

Particularly to say nothing that can be used in print. That’s important. Okay, so from Kennedy’s staff you went where?

Marshall

To Vice President Gore’s staff, and I was working on Congressional Affairs.

Heininger

You had kept your contacts with Gore throughout this process of working for Kennedy?

Marshall

Yes. I’m a political junkie. I volunteered briefly to do some legal work on a Presidential campaign, but I used my volunteer time to work for what was then the [William] Clinton campaign. I would visit with Gore and Gore’s staff regularly. He was elected, and it was a perfect match for me. He became the Vice Presidential candidate for someone I’d been volunteering for. That’s a nice combination for me, and the Senator and Ranny let me take a leave of absence.

Heininger

You took a leave of absence initially to work on the campaign?

Marshall

That’s right. I took a leave of absence to go help with the convention, and while up there, we were putting together the campaign team, against my better judgment. It was probably not the smartest time personally for me to do that, being a young one, but it was a good cause, and that office was supportive. We would run into the Senator on the road, of course.

Heininger

When they won, Gore asked you to stay with him?

Marshall

Yes. He asked me to run the Congressional Affairs office. In interesting ways, my relationship with the Senator evolved into a wonderful and special experience, because I got to engage with him on a range of issues. Whether there’s a Democrat or a Republican in the White House, he has always found a way to be relevant on a wide range of issues. It also meant that because he, like a handful of Senators on both sides of the aisle, is such a traffic cop in the sense that things need to go through them, there were many ways in which the Senator and his staff were not only invaluable to me, but they also could have caused all kinds of problems, good and bad. They could have been helpful on any number of issues, but also, because of occasions when the Clinton administration might have wanted to distance itself from Democrats and the Congress, it could have been much more difficult.

Certainly one of the lessons I learned from the Kennedy staff and from being on his staff and watching him and from then being able to work with him as a White House lobbyist—and also because of the Vice President’s position—I was a Senate leadership staffer also, the only lobbyist who gets to be out on the Senate floor—I was able to see—and I didn’t fully comprehend it at the time—his ability to work out consensus or bipartisan solutions.

Heininger

You saw that more when you were in the White House?

Marshall

I used it more.

Heininger

You used it more.

Marshall

It was almost a given when I was on the Senate staff.

Heininger

Right.

Marshall

It was an assumption. At the White House, for a while I was blessed to have Vice President Gore as a boss, who first of all was a former member of the Senate and indeed was, in effect, Senate family. There were times when that made my job there pretty easy. I didn’t have to explain to him that when they tell you to drop everything because there’s potentially going to be a tie vote and it turns out to not even be a close margin, that it really was going to be a tie vote.

On a few early trips with the Vice President, our office made a point of inviting entire state delegations, or at least both Senators and then the local representatives, to whatever events we were having. In the President’s political shop initially, there was some question about being so bipartisan. I was relieved that the Vice President didn’t flinch about that. Of course the Clinton political staff turned pretty quickly too to do those in a bipartisan way. It was clear to me, from working for Senator Kennedy, that the key to his success was his ability to talk across the aisle. Any Senator who has been successful understands the value of that. Some of the things that have happened in the last few years are scary. But his relationships, in particular with Senator [Alan] Simpson and Senator [Orrin] Hatch, were very instructive. Senator Kennedy will never know how many times during my four or five years as a White House lobbyist that I was able to do my job better because he had me in the room with Senator Hatch and Senator Simpson years before. It’s hard to explain.

Heininger

No, I understand completely. We’ve interviewed Senator Simpson.

Marshall

Senator Simpson was incredible. I was on staff when they would do those minute things, and it was always scary if it was one of my issues. We would all go into a panic, because then you’ve got to deal with the Senator, a tough issue, and Carey, and without much time. Senator Simpson was invaluable in many ways. I’m glad the access to this is restricted because I’d hate for him to get into any trouble for that, but I know he’s proud of that. He’s invaluable to a lot of the early Clinton/Gore stuff, even if he wasn’t fully supportive, with information and with a willingness to keep the communication lines open—and Senator Hatch was the same way.

It was a lesson to me, because Senator Kennedy can be so fiery. Before I had a chance to work closely with him and to see the legislative process, I admired that fire. But it was a lesson for me to see that someone could be that strident and sail against the wind, as some of his fans like to say, while at the same time finding common ground with people who might find some of his comments off-putting if he were not so willing to talk across differences.

Heininger

Was this appreciated, do you think, within the Senate? Was it appreciated outside of the Senate? Was it appreciated in the White House when you were there?

Marshall

Absolutely. Taking the question from back to the front, at the White House, if we had a problem with Senator Kennedy, we had a big problem, but it was not solely because of jurisdiction or seniority. It was because there was always an understanding that he could help bring bipartisanship to an issue. If that important credential were not there, it would be easy for a Democratic administration to succumb to temptation once in a while and try to isolate him on an issue in order to curry favor across the aisle. I never saw that happen, and I have to believe that’s because they understood that he would be able to outmaneuver them across the aisle anyway. You just couldn’t play those kinds of games. There is a handful, probably, of Senators who, in regard to certain issues, you just don’t want to mess with them. We know who on appropriations, on either side of the aisle, you don’t want to mess with. There are two, and it’s been that way for a long time, for example.

Heininger

There are not that many.

Marshall

In reality there are not that many. We did, after all, have a strategy at one point, the triangulation strategy, where it wasn’t directed so much at Democrats as it was at the Hill. But a lesser legislator, in regard to many of the domestic issues that Senator Kennedy was the point person on, could have been isolated, given the communication powers at the disposal of an administration. But that was not going to happen. I like to think, because I’m a Clinton/Gore person, that it’s because we were all on a similar script, at least in terms of endgame goals. But the reality is that, as a practical matter, it just wasn’t wise to mess with him in that way.

Heininger

Once you became Cabinet Secretary, did your dealings with Kennedy change from that vantage point?

Marshall

Yes, because I was not as involved in the legislative process. I would regularly run into him at events large and small, and he used my office a couple of times. I had a nice little office in the West Wing, and Senator Kennedy, being Senator Kennedy, I can’t think of anyone who had as many White House meetings as he had. There were times when it didn’t make sense for him to go back up to the Hill only to come back.

The first time he used the office, I was in Boston, completely by coincidence, for the funeral of Judge [A. Leon] Higginbotham. He used my office. He always asked permission, although, frankly, he could have used my office with me in it. I would have been glad with that anytime. But I was out of town. A staffer, David Thomas, who was in the Gore office, called and said that Senator Kennedy needed a place. Could he use the office? This was the first time he used the office, and I said,

Of course. I’m not even going to be there on Monday, so go ahead.

That Friday night, I said,

I’ll pull out my Kennedy pictures.

He had signed a picture for me in the ’70s. I was in his office to get material. I was in one of his committee offices, and there’s a wonderful picture I have, and I got it specifically the same size as an old Norman Rockwell of President [John F.] Kennedy speaking at the convention. They’re framed the same way. The Senator was kind enough to sign it for me years before I went to work for him, and I never told him I had it because I figure he signs all this—anyway, I grabbed the picture and I swapped it. I swapped a couple of my kids’ pictures and put them up there. Then I went off and I was very pleased with myself. I got back Tuesday, and there was a note on my desk that said,Dear Goody,

which is a nickname—it was words to the effect,Dear Goody, Thanks for the use of your office. It’s very nice. P.S., Next time you pull out some old pictures, don’t dust them off. It was very obvious.

[laughter] There was no way—I can’t believe that anyone in that hallway would have noticed and told him.Heininger

That’s a great anecdote.

Marshall

Actually I went down the hall. I brought it to Greg Craig, who was working at the White House at the time. I brought the note to him, and I said,

I can’t believe I’ve been had,

and he said,Of course. He’s a master.

Greg’s assumption was that the Senator had done that with signed books and things with his own guests. So the few times he borrowed the office after that, I dispensed with this plan, and I left them back in their special place at home. As busy as he is, he didn’t have any business noticing, frankly, but it was pretty embarrassing.Heininger

But obviously his powers of observation are such that he would notice.

Marshall

He’s seen every trick, I guess.

Heininger

You did some trips. You did some of the election monitoring in Nicaragua and Chile. Were you working for Kennedy at the time you did this?

Marshall

Both, yes. I gave him reports on those. He let me go. They were with separate organizations. Particularly for his refugee and humanitarian work, I thought he’d find it interesting. Silly me, he can find this stuff out anyway, but at the time, I thought—

Heininger

But they were personal observations of the elections.

Marshall

That’s right. I tried to give him shorter versions of the reports that I had helped put together. That was a time when I wanted to go on one of the refugee trips that he went on. Those stories were remarkable. I never was able to go on one.

Heininger

Did Jerry Tinker—was he the one who went?

Marshall

Jerry, Michael Myers, and Michael Frazier—and I guess Chris Doherty was always on those trips. But to do them on the holidays, in particular, I thought, was a wonderful message for him to send. I was a fan from afar for so many years. Aside from having great respect for the family, I had interned on Capitol Hill during the Watergate summers, and that’s when I became a political junkie—in particular, a fan and a student of the legislative process, or at least from afar. Combine that with his eloquence on so many issues. I never thought I was going to have a chance to work for him, so when I had that opportunity and it was actually there, it was special.

There were two moments in my life where I thought I had found something I wanted to do and it was never going to happen. That was one where I thought, gee, I’m never going to get a chance to work for Ted Kennedy in a big way. I had volunteered on the campaign, as I mentioned, in 1980. I quit a project I had been working on with some people, helping President [Jimmy] Carter. The other was when I had gotten out of law school and was on a long walk with someone. We stopped at the Lafayette Park, and we were admiring the beauty of the White House at night. That was the beginning of the [Ronald] Reagan era, and I thought, Well, this is never going to happen for me. I had been in there. It’s one thing to set foot in the place, but to actually work in there and to work on legislation and things, I thought, was unfortunately not in the cards for me.

I was in New York—there was only one summer when I didn’t work in Washington in terms of summer jobs, and that was the summer of 1980. My roommate got some tickets way up in the rafters for the convention, and I got to hear the Senator speak, and so many of those words still ring. I counted those kinds of experiences as my big political moments.

Heininger

Little realizing how many more big ones would come.

Marshall

Yes. But I still savor all those moments. They were inspiring and they still are. I could probably do most of the end of that speech but not all of it. I can’t quote [Alfred] Tennyson, but most people can do the last line of the speech.

Heininger

You traveled with Kennedy later on. You went to South Africa with him for Nelson Mandela’s inauguration. What was that like traveling with him?

Marshall

That was very special. Jesse Jackson had the line of that trip in a way. Everyone was jammed into a plane when we went over. People were hanging out in the aisles drinking, eating, and telling stories. Reverend Jackson looked around, and at one point he said,

This is one of those plane flights where if the plane goes down, I’m going to be at the end of the story where it says, ‘Also on board.…’

I mention that not only because it was an amusing line but because, with so many big and memorable personalities with so much to offer, the Senator had such a connection to that cause. I have to believe that everybody on that trip, if they remember one thing other than Nelson Mandela doing the oath, it was that Ted Kennedy was there—and John Lewis. It’s the mantle they carry, not only because of what they’ve done, but because they carry with them, symbolically, the struggles of so many people.It was special to be on that trip with him because I had—I have the picture in my office. When Nelson Mandela came to Washington the first time, he came to the Senator’s office, and the Senator made a point, as he always does when people come to visit, to give up some of his time so that staff can be there. He had the Mandelas there. Bless all three of them. The Senator and the Mandelas sat for pictures, so I was able to witness an historic event. I was not sitting with the Senator at the actual ceremony, but the little cluster of people that we were with was—the whole thing was very moving. If you think about all that that moment symbolized and his mere presence, that in itself is overwhelming. I’m not sure I can think of specific things that were said or done.

Heininger

Who else was on that trip?

Marshall

We continued on. There was a smaller delegation. There was a contingent from the Black Caucus. This is very strange that I’m remembering. I know why I remember this, but David Stern was there, the NBA [National Basketball Association] commissioner. Yes, go figure. I’m blanking on the list. Ed Lewis, who is a publisher, Essence magazine. Then–General [Colin] Powell was there.

Heininger

It was a big group, if I recall.

Marshall

Yes. Linda Johnson Rice, from publishing. I’m sorry. I can probably check, if you’re curious, and see who might have been with him.

Heininger

I’m just curious.

Marshall

I think Chris Doherty was on a trip with Senator Kennedy, but I’m not 100 percent sure. It might have been Mike Frazier.

Heininger

Mike was still there at that point?

Marshall

Actually no. Good memory.

Heininger

I think he had left at that point.

Marshall

But he did some travel with Kennedy, if I’m not mistaken.

Heininger

With the Kennedy network.

Marshall

The advance guys, they’re the lucky few who get to sweat through all those moments where everything’s got to come together, but that also means that they get to do things like be with him when the wall comes down in Berlin.

Heininger

You also participated in a ceremony to commemorate the 25th anniversary of RFK’s [Robert F. Kennedy] death. Tell me what that was like.

Marshall

I’ll never forget that.

Heininger

Who asked you to participate?

Marshall

Mrs. Ethel Kennedy did. I never thought to figure out where that all came from. That family has such a sense of history and family connection that it could have been any number of things. I had a reading that I read. I was so frightened. I then caught a lot of grief immediately thereafter from the old Kennedy hand, Adam Walinsky, who became a friend because of legislation that I was working on for Senator Kennedy. I caught grief from him for not memorizing it. I was not keeping up the Kennedy tradition and preparing properly. Adam was pretty unforgiving. He was right, but it was more that I was frightened to death. Of course I had it memorized, because I sure didn’t want to be reading it and get it wrong.

There were events during my time on Senator Kennedy’s staff when—and they still do this, at the human rights awards, the retreat out to Hickory Hill. If you ever need an injection of inspiration while working on the Kennedy staff, poking one’s head in the Kennedy office or getting to visit Mrs. Kennedy’s house is more than enough to recharge the batteries. I went over there. I brought Adam over earlier in the afternoon, and we were dressed for the event, but most everybody else was in swimsuits or tennis wear. It was fun to hang out there with Adam, but it was the full experience, with people using the zip lines and then frantically pulling on coats and ties to get on the buses to go over to Arlington. I have the video, and I have not looked at it, but I keep telling myself I should.

I remember Father [Gerald] Creedon spoke as the sun was going down. There were so many memorable moments, but to hear him speak, with his voice and his accent—and there were candles on the hillside as the sun was going down. I know that, with very good reason, the family prefers not to mark that day, but I thought it was a wonderfully powerful moment in history that they did that on the 25th. I was struck on that day by Joe Kennedy’s [II] speech. He was a relatively new member of Congress, and I know that had to have been a difficult speech for him. The parade of nieces and nephews at the lecterns also served as a reminder that Senator Kennedy—at least a reminder to me, and just thinking about it now—has the same sort of impact—the family connection, responsibility—that he’s always seemed to feel for the extended family.

It was not unusual for us to get calls with ideas or requests for information about projects from everybody from Mrs. [Eunice Kennedy] Shriver to a couple of her kids. It was, in my world, the criminal justice issues. Juvenile justice issues would come up, for example. I cannot recall whether Senator Kennedy spoke—I don’t think he did—at Arlington. I’d have to check.

Heininger

He was there, though, wasn’t he?

Marshall

Oh, yes.

Heininger

Maybe he wasn’t able to speak. That would have been extraordinarily difficult for him.

Marshall

My family drove up to New York for Robert Kennedy’s funeral. My parents went. My brother and I were at the hotel. That was such a beautiful tribute that he delivered. It’s the only time I have heard him get the least bit emotional, and I was floored by it. It moves me just to think about it. There was recently a staff party in the caucus room for his birthday. It was a huge gathering.

Heininger

Is that the one that Vicki [Reggie Kennedy] set up?

Marshall

Yes, and it was one of many parties.

Heininger

Yes. There are quite a few around that date.

Marshall

I’ve heard him say things, and I thought, gee, that must be so difficult, but it doesn’t seem to affect him. I’m sure it does inside. He mentioned that it was in the caucus room where his brother was announced and so many other things had happened in his life with his family, and he got choked up. It caught me by surprise. I’ve seen him at events before, and I thought to myself, How is he being so stoic? I certainly wasn’t expecting it at a birthday celebration, even though it was in that room. But he’s in that room quite a bit. It’s right across the hall from his office. It saddens me to think that he’s burdened, but I have a great respect for his ability to carry on in such a remarkable way.

Heininger

When you were Cabinet Secretary, didn’t you have something to do with John Kennedy’s [Jr.] plane crash?

Marshall

I did.

Heininger

What did you do?

Marshall

One of my responsibilities was to deal with crashes and disasters, natural and otherwise, and that was everything from small planes to big planes, trains, tornadoes. As a preface, the job was to coordinate the federal executive branch responses to these events, whether it was to try to figure out what would happen if the golfer Payne Stewart’s airplane was—how we were going to address that when the calls would come in. We worked with NTSB [National Transportation Safety Board] or Coast Guard or any number of agencies, sometimes the FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation].

For the John Kennedy plane crash, I got a call—it was an odd coincidence. I’m a Yankee baseball fan, which I hope the Senator will be able to understand. I’d been watching the game. I’m pretty sure it was a Friday night.

Heininger

It was a Friday night. I remember where I was.

Marshall

John was at the game. I was watching and I saw him. I know where the seats are, and part of the reason I remember that was that he was sitting with a mutual friend, Gary Ginsberg, who had worked with me. Gary and I worked closely together on the Gore campaign, and we’re friends. In fact Gary brought John, Jr., by to meet Al Gore at the ’88 convention, so Gary and John were close. To see a friend in the seats, I made a mental note to give him a hard time.

The next morning, I was in the office, and I think [John] Podesta called and asked me to check. He was then the Chief of Staff. That was not unusual. I got calls a number of times about this kind of thing. There’s a button in a lot of commercial cockpits that you hit if you have a hijacking. It’s not supposed to work by accident, but they do activate by accident. I’d get those calls. I got a call once that John Glenn’s plane had disappeared. He was tired and decided to take a break, but things like that—it was not unusual to get those kinds of calls. I got the call, and I thought I’d check it out, and I couldn’t find out anything, and I called Gary. Then we realized that we did have a potential disaster. One of the issues that then came up was Coast Guard and Navy looking for wreckage. We had some issues.

I should put in a plug for President Clinton at this point, because the press was starting to get cranky about the costs of searching, and President Clinton didn’t flinch at all. I was ready to explain to him the processes, the costs, and the timelines and things. It wasn’t because he was too busy. He had already processed all of this and said,

We ought to continue doing everything we can to find wreckage.

A close friend of mine, Peter Goelz, was working at the Transportation Safety Board and was on site and was briefing Senator Kennedy and his staff. Some of those calls Peter and I would do together. At that point, I think the Senator was already up in Massachusetts. Not a single one of those calls was anything I’d ever want to have to relive. I will say, for purposes of this process, that the Senator’s demeanor was the most soothing thing. It was another one of those moments where I thought, how is this man making us feel more at ease? I spoke a couple of times with Kerry Kennedy during that period, and it was the same sort of thing. The family has an ability to be serene in times that are more trying than anyone should have to bear.

When Peter Goelz called to tell me that they had indeed found and were recovering the bodies, it must have been, I don’t know, two or three in the morning. It fell to the two of us to place the call to the Senator, and at that point, it had been days. The outcome was pretty obvious, but I didn’t view it at the time as the kind of call—maybe one never would—that might bring somebody under those circumstances some peace. I viewed it as yet another awful turn in a terrible chapter. It was an awful call to have to make. Peter and I weren’t explicitly saying to each other,

We’re going to take a minute and take a breath here,

but we did. He was on the phone. It was 3:00 or 4:00 am, and it was the same Senator Kennedy who had been through those days of calls.I hate to talk about steel in spines when he actually suffered a broken back once in his life, but the guy is amazing—absolutely serene and appreciative. Caroline [Kennedy] was the same way. She wanted to know who needed to be thanked for all these efforts. Kennedy gave Peter a beautiful glass sculpture of a ship. Here’s somebody you want to do something for, and you don’t know how to comfort him, and he’s—

Heininger

Doing the other.

Marshall

Yes. The lesson to take from it is that there’s no better way to address those things. If you go through anything even remotely like that, I don’t think it’s what comes to mind as one’s natural reaction.

We also had to place some calls up there after that process, about ceremonies. The White House Press Corps was being a little nosy about things. The Senator said,

Enough.

For people who have been intruded upon throughout their lives in many ways by the glare of the press or others, it’s hard to fence off sometimes. The moment we got the sense that people were getting near that, we were only too happy to help.Heininger

Tell me about your family’s relationship with the Kennedy family.

Marshall

My father was put on the second circuit by President Kennedy. He came to Washington and worked at the Justice Department. He had been nominated by President [Lyndon] Johnson to be Solicitor General. When President Johnson nominated him to the Supreme Court, as I had mentioned, Robert Kennedy—I may be confusing this with the second circuit, but I thought it was the Supreme Court nomination hearing. Robert Kennedy sat with him, and Senator Ted Kennedy was on the dais.

Heininger

The timing would be right, I think.

Marshall

Sixty-seven.

Heininger

Yes.

Marshall

I’m sorry. The thought popped in my head about that.

Heininger

That was the introduction, yes.

Marshall

I hope it will come to me. It was something related to that that popped in my head. Both Senators, Robert Kennedy and Ted Kennedy were, by all history reports and by my father’s reckoning, pivotal in getting him confirmed behind the scenes for the second circuit judgeship in particular, but also for getting things moving on the Supreme Court nomination. I’m fairly certain—I’m not 100 percent certain—but there were more

no

votes on his nomination than there ever had been before, so it wasn’t exactly an easy one. It was nothing like what’s happened since, but at the time, it was noteworthy.On the second circuit nomination, Senator [James] Eastland from Mississippi had been holding that nomination for quite a while. Robert Kennedy was Attorney General and came up with—I should know the details of this—a compromise to free him up, a trade, to which Senator Eastland supposedly famously said,

Then tell your brother he can have his nigger.

It was the kind of backroom dealing that had to occur and in the old days of the Senate was more frequent, I think. The stories don’t get out for years and years.Heininger

The stories don’t get out, but I think the trades like that are still there.

Marshall

Yes, the stories get out a little more quickly.

Heininger

Particularly on nominations, the trades clearly are still there, but stories like that don’t get out.

Marshall

Not any time soon, and for good reason. You don’t want to burn—

Heininger

For good reason, yes.

Marshall

Those kinds of connections go way back. My parents have an interesting situation in that regard, because they also felt a lot of loyalty to the Johnsons. To read the stories about the time in some of the books is a little too camp sometimes. You could fast forward, and when I worked for Senator Kennedy and working on—I guess anything I worked on with him was my favorite thing for me to work on—but I worked on, among other things, something I inherited from Jeff Blattner, which was the Racial Justice Act, dealing with race in the application of the death penalty. Senator [Charles] Robb had a new staffer who was fully focused on this. They were neighbors at one time, Robb and Kennedy.

Heininger

Yes, for a long time.

Marshall

That was enjoyable to watch.

Heininger

For a long time, until he moved into the District. I think Robb still has that house.

Marshall

He does.

Heininger

What did you think when Clarence Thomas was nominated to replace your father?

Marshall

I was looking forward to seeing how the committee would handle that. I can’t recall having a reaction on the nomination. I was deeply saddened that things took a turn—well, there’s no other way to say it—to the bizarre.

Heininger

It was.

Marshall

It wasn’t a pleasant thing to see. As a student of the Congress and particularly of the Senate, it wasn’t pretty. I did not work on the nomination, but being around Jeff and Carolyn was interesting. There was a question about what Senator Gore was going to do. I did some checking on that. His is one of those offices where if they’re invested, they’re fully in, so any vote or any questionable vote, they’re going to try to find a way to work it.

There was another nomination that was more interesting, for me at least, the [Robert] Bork nomination. I wrote Gore’s statement on that, and at that point, he was running for President and running hard in the South. I had a feeling that he was going to vote against Bork. I had no guidance. I just had a feeling that he would but that he was going to hold back as long as necessary, which, of course, got the interest of the Kennedy people because they were trying to work that hard. Not knowing if there might come a day when I would work for Jeff and Carolyn, I was fending them off, but also getting some help from them in terms of how to phrase his statements and speeches. There are not a lot of offices on the Hill—there are some—that outsource in that way. I’m sorry, I’m blanking about another Bork experience we had.

Speaking of outsourcing, Kennedy is famous for loaning staff, even to people who don’t need it. To this day, I have a pretty good relationship with Senator [Christopher] Dodd because of one night when Senator Dodd was having trouble getting parental leave attached. I was staffing the Senator on it, and we were there with the two Dodd staffers. Kennedy left for dinner and said,

Stay here. Whatever he needs. Excuse me,

and I thought, of course. Not only am I wedded to the cause, but if the boss is going to take a break on something that was prescheduled, but he’s coming back, how could I abandon this? He would regularly task his staff to help other offices. I don’t recall other people getting those kinds of assignments too often. It’s a busy place.Heininger

Did you feel that Clarence Thomas was a worthy successor for your father, or would you have preferred to see someone else in that position?

Marshall

I’ve tried to come around to thinking on that. It’s hard for me to address that question in those terms, because it gets back to whoever won the last election. I don’t feel that President [George H.W.] Bush was obligated to come up with a worthy successor to my father. I believe that my party failed to put in motion a set of circumstances that would put a person in the White House who could try to do that. The Democrats who have been appointed since my father served, I think, have been noteworthy additions to that Court.

Heininger

Did you personally feel the opposition to David Souter that Kennedy felt? He certainly hasn’t turned out the way Kennedy had expected.

Marshall

No. I worked a little bit on that nomination, and I found his writing to be arcane. At the time, I didn’t know what to think, so I figured, catch these speeches and see.

Heininger

You were also dispatched, when you were in the White House, to the Judiciary Committee to deal with the Zoë Baird nomination.

Marshall

A little bit.

Heininger

What was that about?

Marshall

That was more intelligence gathering. There were two things going on almost at the same time. That preceded, because we also had a problem in that committee with Lani Guinier’s nomination, and Senator Kennedy was working to get her.

Heininger

Which one came first?

Marshall

I feel as though they were about the same time.

Heininger

They were at about the same time, but I think Zoë Baird came first.

Marshall

Zoë Baird was first, right.

Heininger

Then Lani Guinier came, but you’re right, the timeframe was compressed in there.

Marshall

That was more intelligence gathering and just trying to report back to Howard Paster, who was the senior White House lobbyist. I don’t recall dealing directly with Senator Kennedy on that—a lot of conversations with Jeff Blattner, though, taking temperatures. I’m prone to tangents.

Heininger

That’s all right.

Marshall

That’s why I have to have to calm myself down about the—

Heininger

That’s the beauty of oral history.

Marshall

It’s not unusual in the Kennedy world to have people pop through there. There’s no expectation of running into people on Capitol Hill, even though it’s a pretty special place. During my time there, we had a project for Muhammad Ali. We had one that the Senator personally put together, and Kathy Kruse and I staffed him on it, where we had about a dozen songwriters. It included Sammy Cahn and Henry Mancini, and the Senator had this great idea. It was totally his idea. I was doing the substantive part of it. Kathy had the idea to organize it as an event—it was for digital audio recording issues, to try to protect the authors’ rights—to get one of those small rooms on that first hallway when you walk in, under the Senate steps there.

Heininger

Yes, right.

Marshall

There are a few little meeting rooms there.

Heininger

Yes, there are.

Marshall

Get one of those rooms, put a piano in there, and put these guys in there, and then he would run around the Senate floor during votes and tell his colleagues that they were down there. He had already gone down there a couple times to tell these folks that Senators would be coming and going. You’ve all seen the talking points, and he recited them. He does so much by example. He recited all the talking points that we had given him, without reading them, and so

if he could do it, surely they could

was the underlying message there. Aside from having such a wonderful idea, a compelling way to sell this, which was his idea completely, what a treat to be able to—because there were times when no one was coming in, so Kathy and I were sitting there with these folks who were just playing the piano and telling stories.For Muhammad Ali, we had a project. We couldn’t get it done that time, but it was to deal with his draft—he was a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, and I think it might have been expunging the record or clarifying it, because it was on a crime bill.

Heininger

Wasn’t it expunging the record?

Marshall

It might have been something like that. He and Orrin Hatch had it in their heads that they were going to take this on, and I think it may have come initially from Senator Hatch. Senator Kennedy had crossed paths with Muhammad Ali regularly over the years, but it was done as one of those tax transition kind of things. It was drafted, and only Kennedy and Hatch and their staffs knew.

Heininger

Knew what it was.

Marshall

It was drafted as, yes,

The criminal record,

blah blah blah. They took turns with Muhammad Ali for a while on the day that we were trying to get this through, and the staff people turned. Judge Randy Rader was Hatch’s guy at the time. He’s a judge at the federal circuit now. Randy and I, our names were beside this—Kennedy and Hatch—and we were staffing it, so our names were there. Everybody who worked on the bill was in a room working through the last parts, and they said,You owe it to us, as part of this process, to tell us who this is for.

We knew at some point we were going to have to do it, and Randy had him across the hall, so he brought him in.Heininger

Oh, wow.

Marshall

It should have worked, but eventually it didn’t. Senators lead these interesting lives. They get to do these sorts of things.

Heininger

Did it actually make it through?

Marshall

It didn’t make it on that bill, which is the most amazing thing.

Heininger

Did somebody notice it?

Marshall

No. It was something about transitions. I think the deal was it had to be by name or else—I thought it was that one Senator objected and said it had to be by name or he or she was not going to—

Heininger

Did it eventually get done?

Marshall

I don’t know. I should and I just don’t.

He had great common sense things too that he would do. Drug-free school zones were very popular. One day he said,

We ought to have these gun-free school zones,

blah blah blah. I heard it, and I thought it was a slip, and he could see that I wasn’t following him, so he said,Can we do something on that?

I realized that we were talking about drug-free schools, and in the midst of that, he decided he wanted to try something else. We ended up trying to do that. We failed a couple of times while I was there, and then he did it with Senator [Herbert] Kohl. I think he let Senator Kohl grab that one, but it got through, and then it went to the Supreme Court and got tossed out. I think they had to redo it. But he would just come up with these things.I gave him one. There was only one time I can recall, at a counsels’ meeting at the Judiciary Committee, where everyone applauded something the Senator did. It was when he had Bill Bennett in for nomination to be the first drug director, drug czar. Bennett came in with fanfare and a big picture of him on the front page of the Post, playing touch football, looking so dynamic—clearly a brilliant individual. The Senator had an idea he wanted to ask him about, because drug testing was the craze, but he didn’t want to telegraph the question. Bennett’s lobbyists were good. They were reasonable about things. Even on the front end, before he was into his nomination hearing, they were good about keeping everyone informed. They came around on the questions.

Something told me that I shouldn’t be running through the Senator’s questions without checking. Indeed, Carolyn and Carey didn’t think it was a good idea. It was the right thing, because there was one thing we were going into that we didn’t want him fully prepared on. Being a smart guy, we wanted his gut reaction to something, and it was an issue that I had never heard of before that—drug testing for guns. It was not so much to get that as a policy; it was to use that parallel to expose how overused drug testing was becoming.

I wish I had the transcript, but the way the Senator teed it up was way off of what Carey or I or anyone else had written at that point. He took that stuff in the morning and looked it over and came up with this thing. He went into a speech about,

Drug testing, certainly there’s some value, but there are also other kinds of testing. We test people for licenses to cut hair,

and he went through this whole Kennedy thing. He had Bennett conceding that drug testing was important and valuable. Of course he would do that. This is a big deal.Then the Senator said something like,

There are X number of gun sales on any given day in the United States. How do you feel about drug testing people before they buy a gun? Because those are dangerous items, I believe, to truck drivers and things.

It was a moment. Bennett had been on a roll for weeks, on a rollout. It wasn’t a bad moment either, because Bennett was pretty charitable about it, but it was a moment where everybody in the office had an idea, and then the Senator that morning turned it into something much more.The first bill I worked on with him was—it will be surprising to you, given your Hill experience—it was not something that he fully conceived, because it was a huge joint effort and it was bipartisan, but he was very much a driver behind this. It was a bill that was both authorization and appropriation in the same bill. I think it was the only one that had been done that way. If it was done before, it wasn’t done often, and it was not done on a comprehensive issue. I mention it because we did it when Senator [Joseph] Biden was on extended leave. Biden was chairing the Judiciary Committee, so we had an absent chairman. There were a number of committees involved, but on drug policy, a lot of that stuff is either the crime stuff for Judiciary, or treatment and education, which is the HELP [Health, Education, Labor, & Pensions] Committee.

Heininger

Right.

Marshall

Kennedy was chairing HELP, or what then was Labor. We had an absent chairman at Judiciary, whose staff was tremendous, but there was a lot going on, and it was on a fast track. Then all sorts of great stuff was done in there. It was historic in the sense that it had the authorization and the appropriation. I know many people had a hand in making sure that it was all together in there.

The huge accomplishment for the Democrats—and Kennedy believed in it fervently and still does—was that everything in there, whether it was an authorization or appropriation, reflected a 50/50 split between law enforcement and demand reduction. This was classic Kennedy. Years before I worked for him, he and Biden were both big on gun control but also on supporting police and cops, the notion that you could do one or the other, but it’s much more formidable to have them linked together. There are plusses and minuses that come from that. You can end up with people ratcheting up penalties in order to balance off the demand reduction, treatment, education. But every time you ratchet a penalty, if they’re linked, that gives you an opportunity to raise opportunities for people to get out of the cycle of drug abuse. He was justifiably proud of that. It’s something that I think a lot of policymakers in the field continue to—

Heininger

Miss.

Marshall

Yes, they miss. They continue to try to pay homage to it, in some respects, but at least it’s there and it forms a debate.

There was a provision that was all his—it came from one of his issue dinners—that was in that bill, which is still a big funding source for a lot of localities and states, which is called HIDTA money, High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas. He had seen some materials that were put together for him in connection with an issue dinner on drug abuse and crime that he had. Robert Morgenthau, who is the D.A. [District Attorney] up in Manhattan and who had been a close policy advisor to Robert Kennedy when Robert Kennedy was the Attorney General, came down for the policy dinner, and they ran through this. I think it was called

crime crackdown policies.

In some neighborhoods, if you show up, it’s,

Make sure there are no more broken windows. Anything that looks illicit, you grab them, grab anyone, and check them out.

It was one of those shock-to-the-system things as opposed to a long, sustained, grab-anyone-that-moves kind of thing. The notion that you could come in, and the ways in which communities responded—because then the people in the community would be more willing to be out and about. It evolved into a High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area—basically a grant program. I’m pretty sure that the ONDCP [Office of National Drug Control Policy], the drug policy folks, that’s their pork when they run around the Hill. When we would say that we wanted some of that money, the drug director’s office used to say,Everyone claims that they worked on that.

It’s so often the case. It was Senator Kennedy who had all those hearings.Heininger

What’s your favorite memory of Kennedy?

Marshall

I won’t ever forget when he and Vicki sat with our family at my father’s funeral. My mother wanted that more than anything—and the Robbs. I’m not sure there’s any particular moment. Aside from being obviously grateful for all that I have learned, I think there must be dozens of moments where he brought tears to my eyes because he was so funny. He has a great capacity to bring joy to people’s lives by telling a funny story or by poking fun at people. He has great reactions to things. He’s large in so many ways. That’s probably more memorable than anything else for me, aside from poignant moments that I’ll carry with me because they’re special and moving.

I walked in one day. I discovered the hard way that I have an allergy to poison ivy. I had gotten it on my clothes, and I rubbed my face. It was—

Heininger

Nasty.

Marshall

Yes, it was bad. I came in to brief him, and he looked up, and he’s so—if you go in and brief him on a busy day, he’ll generally give a couple of pleasantries, but let’s get down to it. He looked up, and it was one of those kinds of days, but he put his pen down and said,

Jesus Christ! What happened to you?

I thought I deserved that, but it really was—Heininger

A run-in with a poison ivy plant.

Marshall

Yes. I didn’t even know how to explain it, because it was too embarrassing.

Heininger

I don’t know. That’s pretty nasty stuff. I’ve had it too many times myself.

Marshall

It gets me out of yard work.

Heininger

Lucky you.

Marshall

He’s been wonderful the times my kids have been in there. For a person who is as busy and in demand as he is, he has a wonderful capacity to make everyone’s interaction with him memorable.

I have a friend, who is a client now, who worked for Slade Gorton and Warren Rudman, two Republicans who could be fairly moderate. She went to work for the first Bush administration on some domestic policy issues and was negotiating ADA, Americans with Disabilities Act. She was in one of the final negotiations in Senator Kennedy’s office. Carolyn, I believe, was there for this. She put her purse down, and Barney—I want to say Barney. Was it Barney? I can’t remember which dog it was. I babysat that dog a couple times, but then he kept nipping at my child.

Heininger

That’s reason enough not to.

Marshall

In a fun way, but it scared him. Barney devoured Carolyn’s purse.

Heininger

Oh, no.

Marshall

Of course the Senator was mortified. One day later, spanking new purse, even nicer than the one she had, hand delivered to her office down at the Executive Office Building, which, on the one hand, was the least he could do, but still. I loved the old staff network. Then there were the indirect ones, like Adam, who I continue to follow around. There’s so much history there, it’s remarkable.

Heininger

This has been fascinating.

Marshall

I ran over. I hope I hit what you needed.

Heininger

This has been absolutely fascinating. Yes, you absolutely did.