Reluctant reformer

Nearly every new president of the modern era has viewed the nation’s immigration policies as deeply flawed. Yet few of these modern executives have been willing to make immigration reform—one of the most dangerous issues in American politics—central to their agenda. Even fewer have had a measure of success doing so. The most dramatic and successful of all—Lyndon Johnson’s landmark 1965 reform—itself followed a pattern of steep political costs and uneven policy results. Yet it also captures the transformative possibilities of remaking U.S. immigration law for countless newcomers and larger national interests.

Today, as in the past, efforts to significantly revise U.S. immigration laws and policies have produced major political divides that explode even the most unified party coalitions and that make straightforward problem definition a pipedream. Campaigns for sweeping reform in this arena regularly have followed a tortured path of false starts, prolonged negotiation, and frustrating stalemate. When lightning has struck for passage of non-incremental reform, enactment has hinged upon difficult compromises over rival goals and interests.

The result is legislation that is typically unpopular among ordinary citizens, compels key stakeholder groups to swallow bitter pills, draws fire from determined opponents, and places new and often competing policy demands on the national state. These dynamics—intraparty conflicts, elusive problem definition, difficult compromises, and unpopular outcomes—typically have led most American presidents to proceed with caution.

Lyndon Johnson was well aware of these challenges as a first-year president, yet he forged ahead knowing the fight for sweeping immigration reform would be far more taxing and unpredictable than nearly all of the legislative proposals on his immense agenda. He did so recognizing that failing to spearhead an immigration overhaul would significantly undercut his civil rights, social justice, and geopolitical goals. The Johnson administration learned that major reform hinged upon the formation of “strange bedfellow” alliances that are unstable and that demand painful concessions. But his White House also understood that the levers of immigrant and refugee admissions both reflected and served larger visions of nationhood, and it refused to let nativists continue to monopolize those terms to codify their ethnic, racial, and religious animus.

Johnson ultimately expended far more political energy on this issue than anyone on his team anticipated, with bedeviling twists and turns on the path to major reform. His remarkable legislative achievement also had dramatic unforeseen consequences over time, including an unprecedented change in the country’s demographic landscape. Yet it also enabled Johnson to upend xenophobic policies that had prevailed for a half-century, and to project very different ideals at home and abroad. Johnson’s battle for reform underscores the alluring capacity of immigration policy to be a potent tool for nation-building, one that will naturally appeal to presidents committed to higher forms of statecraft.

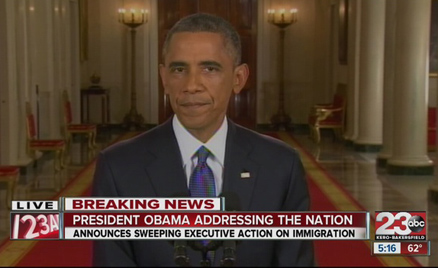

For all of its possibilities to reshape U.S social, economic, and political life, immigration reform has made most modern presidents decidedly uneasy. Franklin Roosevelt assiduously avoided clashes with immigration restrictionists in Congress during the 1930s, a period when draconian national origins quotas barred entry for most newcomers and nativist demagogues blamed unemployment on past arrivals. Decades later, presidents such as Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton pursued a cautious, reactive strategy toward immigration reform, one in which they responded opportunistically to congressional initiative on the issue. Most recently, of course, the incoming Obama administration shelved immigration reform when it became clear that nearly every Republican member of Congress (and some Democrats) would derail legislation. When pressed, Obama eventually followed precedents begun by Truman and Eisenhower by taking unilateral executive action to provide deportation relief and economic benefits to particular undocumented immigrants, most notably young people who entered the United States as children (and later their parents, a move currently blocked in the courts).

Reticence on this issue, let alone avoidance, will be all but impossible for the next president. Given the unequivocal promises made by every major candidate during the 2016 campaign, whoever moves into the White House in 2017 will be under enormous pressure to act decisively on how immigrant admissions and rights are governed. Going it alone via executive action will be viewed at best as a band aid measure that satisfies few, or at worst as a crassly partisan maneuver that is constitutionally suspect and worthy of harsh congressional, judicial, and popular sanctions. In short, the pursuit of major immigration reform will be both daunting and nearly inescapable for the next president. However, this challenging effort need not be as ill-fated or politically damaging as those of Jimmy Carter, who pursued employer sanctions-amnesty legislation, and George W. Bush, who hoped for comprehensive immigration reform.

Lyndon Johnson on immigration, January 8, 1964

As an unexpected first-year president, Johnson stands out as a reluctant champion of long-sought immigration reform who ultimately won passage of the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). Despite enormous legislative advantages, the Johnson administration’s battle for the INA was anything but easy. Indeed, it provides an especially instructive window onto the formidable hurdles, painful compromises, and transformative consequences of significant innovation in this contentious policy arena.

Although Johnson pledged to fulfill the agenda of his slain predecessor, and no other president was more closely identified with liberal immigration reform than John Kennedy, LBJ initially made it clear to White House advisers that he wanted nothing to do with the issue. For years he was whipsawed by immigration policy in the Senate, where Democrats were deeply divided between southern conservatives opposed to any opening of the gates and northern liberals committed to dismantling racist national origins quotas that reserved about 70 percent of visas for immigrants from just three countries: Great Britain, Ireland, and Germany. According to reporters, Johnson exploded with invective as Senate Majority Leader when asked about holdups to progressive immigration reform during the 1950s. While Kennedy described immigration reform as “the most urgent and fundamental” item on his New Frontier agenda, he got nowhere on plans to alter U.S. immigration law due to potent opposition from conservative Democrats like Senator James Eastland (D-MS) and Representative Michael Feighan (D-OH), who controlled the immigration subcommittees of both houses. These lawmakers stood atop a bipartisan coalition that favored immigration restriction in the name of national security, job protection, and ethnic and racial hierarchy.

As a new president, LBJ told advisers that the issue was a political buzz saw that lacked public support and could hurt other reform plans. Yet numerous aides argued that the persistence of national origins quotas for selecting immigrants contradicted his goals at home and abroad. These draconian quotas were inconsistent with his civil rights agenda “to eliminate from this Nation every trace of discrimination and oppression that is based on race or color,” and they provided, as Senator Philip Hart (D-MI) put it, “grist for the mills of Moscow and Peiping.” Johnson became a late convert to immigration reform.

Johnson’s first State of the Union Address in 1964 buoyed the hopes of immigration reformers. In this speech, LBJ outlined a civil rights agenda that championed for all citizens access to public facilities, equal eligibility for federal benefits, an equal chance to vote, and “good public schools” for all children. Then he added, “We must also lift by legislation the bars of discrimination against those who seek entry into our country.” An administration bill was soon introduced that would increase annual immigration to 165,000 and replace discriminatory per-country quotas in favor of a preference system allocating 50 percent of visas on the basis of special occupational skills or education that benefited the national economic interests. Remaining visas would be distributed to refugees and those with close family ties to U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents (LPRs).

One week after his address, Johnson held a press conference at the White House that included members of the House and Senate immigration subcommittees as well as a broad and diverse set of advocacy group leaders favoring reform. As the restriction-minded Eastland and Feighan looked on uneasily, Johnson went before a phalanx of reporters and television cameras to urge Congress to make U.S. immigration law more egalitarian. He reminded lawmakers that every president since Truman believed that existing immigration policies hurt the nation in its Cold War struggle with the Soviet Union. Johnson then invoked the language of Kennedy’s inaugural address, urging a meritocratic admissions policy that asked immigrants, “What can you do for our country?” “We ought to never ask,” he added, “‘In what country were you born?’” Leading congressional sponsors of the administration’s bill, including Senator Hart and Representatives Emanuel Celler (D-NY) and Peter Rodino (D-NJ), praised the measure. When they finished their statements, Johnson caught Eastland off guard by asking him to address the assembled journalists and policy activists. A surprised Eastland told the gathering that he was prepared to look into the matter “very carefully and very expeditiously.” After a series of tense Oval Office meetings with Johnson in 1964, Eastland stunned Washington observers by agreeing to temporarily relinquish control of his Immigration Subcommittee to none other than the freshman senator from Massachusetts, Edward Kennedy. Johnson’s unusual influence over Eastland removed a formidable impediment to the Hart-Celler bill, but major legislative hurdles remained.

As chair of the House immigration subcommittee, Feighan made headlines in 1963 for charging that the CIA was infiltrated by Soviet spies and that the actor Richard Burton should be banned from entering the country for having an “immoral” affair with Elizabeth Taylor. A year later, Feighan mobilized restrictionists in both parties to block Johnson’s immigration bill. Instead, he proposed a rival bill that promised to preserve preferences for northern and western Europeans, exclude nearly all Asians and Africans, favor immigrants with family ties under existing quotas, and maintain exclusions for ideology and sexual preference. This maneuver ensured that no action would be taken until after the 1965 election.

The Johnson team renewed its push for immigration reform in 1965, yet Feighan and his allies held two months of hearings in which they peppered administration officials with questions about a new merit-based preference system and its potential impact on the number and diversity of newcomers. “How about giving the welfare of the American people first priority for a change?” he asked proponents of progressive reform.

Frustrated by Feighan’s roadblocks, LBJ and House Democratic leaders successfully moved in the spring of 1965 to expand the immigration subcommittee to add Johnson loyalists like Jack Brooks (D-TX) as crucial swing votes. Despite this tactical blow, Feighan privately told anti-immigrant lobbyists that he enjoyed enough bipartisan backing to seriously limit radical policy change. Yet Feighan also understood that Johnson and reformers now had sufficient political momentum to overcome delaying tactics, and entered tough negotiations with the White House.

In the end, Feighan and his allies agreed to dismantle the national origins quota system and the so-called Asiatic Barred Zone if Johnson sacrificed the administration’s emphasis on immigrant merit and skills. Feighan was convinced (incorrectly, as it turned out) that reserving most visas for immigrants with family ties to U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents would decidedly favor European applicants and thus maintain the nation’s ethnic and racial makeup. The new legal preference system in the administration’s bill established four preference categories for family reunification, which were to receive nearly three-quarters of total annual visas. Spouses, minor children, and parents of U.S. citizens over the age of 21 were granted admission without visa limits. The revised bill left roughly a quarter of annual visas for economic-based admissions and refugee relief.

Along with the legal preference system, the “non-quota status” of Mexican immigration in particular and Latin American admissions in general were a prominent concern for restrictionists in both houses of Congress during the legislative wrangling of 1965. The notion of a cap on Western Hemisphere immigration was adamantly denounced by Secretary of State Dean Rusk and other foreign policy advisers, who argued that taking such a step would be a huge setback to relations with Central and South American countries. The administration’s stand on Western Hemisphere immigration came under withering attack in the Senate, however. In particular, southern Democrats led by Sam Ervin, Jr. (NC) threatened to stall action in the Senate immigration subcommittee unless concessions were made. Facing a major logjam, Johnson and pro-immigration lawmakers compromised with Ervin and his restriction-minded colleagues on an annual ceiling for Western Hemisphere immigration. As LBJ’s congressional liaison Lawrence O’Brien explained, “Listen, we’re not going to walk away from this because we didn’t get a whole loaf. We’ll take half a loaf or three-quarters of a loaf.”

Even by the outsized standards of Lyndon Johnson and his Great Society juggernaut, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1965 was monumental. The new law marked a dramatic break from immigration policies of the past by abolishing eugenics-inspired national origins quotas that barred nearly all but northern and western Europeans. In their place, the INA established a preference framework that continues to guide American immigrant admissions, with family ties receiving highest priority followed by occupational skills and political refugee status. The product of contentious political wrangling, this immigration reform ultimately transformed the demographic makeup of the country. Although few historians believe that the INA’s champions anticipated just how profoundly it would change the U.S. demographic landscape, Johnson recognized that its passage was especially significant—enough so that he oversaw the staging of an elaborate signing ceremony at the base of the Statue of Liberty. True to form, White House staffers were given strict instructions by the president to physically block political rivals like New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller from the cameras assembled on the dais at Liberty Island. Hinting at the INA’s potential impact, Johnson predicted that the new law would “strengthen us in a hundred unseen ways.” Fifty years later, this sweeping immigration reform is being commemorated alongside the Voting Rights Act as one of the crowning—and most controversial—achievements of the hard-driving Johnson years.

Lyndon Johnson stands apart for successfully shepherding landmark immigration reform through Congress. In many respects, LBJ enjoyed many exceptional advantages in championing the INA, including its close association with his martyred predecessor and broader civil rights reform; a near consensus of foreign policy experts that reform served national geopolitical interests; a strong economy; an electoral landslide in 1964 and, concomitantly, huge partisan gains in both houses of Congress. The fact that these especially favorable circumstances did not make the Johnson administration immune to an arduous legislative struggle underscores the enormously daunting political barriers that usually emerge when major immigration reform is at stake. The INA was decades in the making, and its enactment in 1965 was trying and uncertain despite being attached to Johnson’s Great Society juggernaut.

It is equally revealing that in the end, Johnson’s success in winning passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act depended significantly upon painful compromises, including cross-cutting reform packages that both expanded and restricted immigration opportunities in new ways. Whether one celebrates or condemns the INA, it is clear that this law defies simple characterization precisely because it is an intricate statute with multiple meanings and impacts. The headlines then and now are not wrong: the INA marked a monumental watershed in U.S. immigration policy by ending a draconian national origins quota system that was explicitly rooted in eugenicist notions of Northern and Western European superiority. That fact that it took 20 years after the defeat of Nazi Germany for Congress to remove these barriers in American immigration law speaks to how effectively Cold War nativists knitted together racial hierarchy and national security fears. This history made it especially fitting that the Johnson administration coupled the INA with the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. It is equally true, however, that opponents of diverse immigration left their imprints on the INA by winning new limits on Western Hemisphere immigration and by making family ties rather than individual skills the keystone of the legal preference system. In the final analysis, the Hart-Celler Act is a reflection of the arduous struggles between Johnson, reformers, and congressional stalwarts over its form and substance. The dramatic and unanticipated demographic shifts that these restriction-minded provisions helped spur underscore the INA’s transformative, yet variegated, influence on American life.