About this episode

May 14, 2017

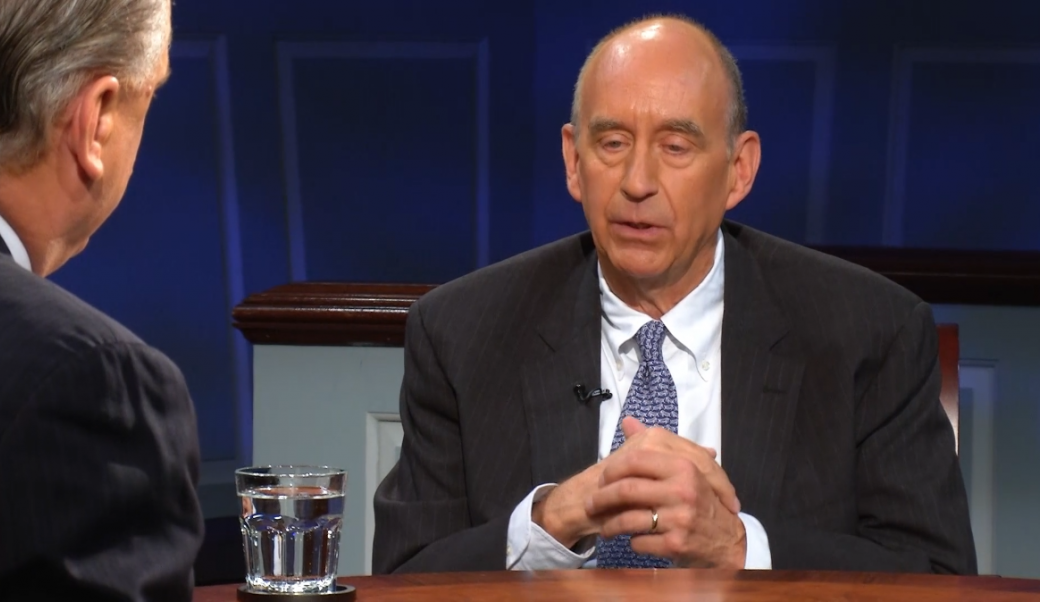

John Farrell

Author John Farrell, a contributing editor to Politico Magazine and former White House correspondent for the Boston Globe, discusses his new book, "Richard Nixon: The Life."

The Presidency

Richard Nixon: The life

Transcript

Douglas Blackmon in Studio: This week on American Forum, a hot new biography on Richard Nixon with its best selling author, Jack Farrell.

MAIN TITLES/MX

Douglas Blackmon: For six years, our guest in this episode has been trolling presidential libraries and museums for material, to write a new biography on a former president people can’t seem to get enough of. Jack Farrell’s book about the life of Richard Nixon, all 737 pages, including notes and index, is one-stop shopping to learn about our 37th president, who served from 1969 until 1974, when he became the only U.S. president in our history to resign from office. From the secret White House tapes that captured the nation in the 1970s, to a complicated personality bordering on paranoia, to his intense but distant love for his family, the Nixon presidency has been a gift that kept on giving for scholars and students, of the complexity of human beings and the ways even extraordinary individuals can destroy themselves. This new book, Richard Nixon: The Life, breaks new ground. For years, scholars have argued about what is known as the Chennault affair, the alleged use by then candidate Nixon, of a backchannel connection to delay Vietnam War peace talks until after the 1968 election, thereby hurting Hubert Humphrey’s chances to win the presidency and helping his own. Jack Farrell may have solved the puzzle. This is his third book. The other two were on former Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill, and famed attorney Clarence Darrow, of the 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial." Farrell was also a newspaper reporter at the Denver Post and the Boston Globe, where he worked on the paper’s legendary Spotlight reporting team, the oldest, continuously operating newspaper investigative journalism unit in the country. Jack Farrell, welcome to the program.

John Farrell: Glad to be here.

2:26 Blackmon: Let’s go right into the—it’s just a sliver of your book in some respects, but let’s go right into the thing that’s gotten the most attention; these notes that you found that speak to the question of whether Richard Nixon, in 1968, may have, via Henry Kissinger and others, been involved in trying to delay a resolution to the Vietnam War, out of fear that a successful peace negotiation would have helped his Democratic rival.

FACTOID: Kissinger was Nixon’s national security advisor, secretary of state

FACTOID: 1968 Vice President Hubert Humphrey was Democratic Nominee after LBJ withdrew

And so the idea that he perhaps violated the law by encouraging a delay in the end of the Vietnam War. But so just go right to it. What did you find and what does it tell us?

Farrell: What I basically did is find a piece of a jigsaw puzzle that other historians have been putting together for decades, especially most recently, Ken Hughes here at the Miller Center.

FACTOID: Hughes’ books include Chasing Shadows and Fatal Politics

Going through the most recently released files at the Nixon Library, I came upon a group of notes kept by Bob Haldeman, who was Nixon’s chief of staff in the ’68 campaign, and in them, he clearly records Richard Nixon telling him keep Anna Chennault working on the South Vietnamese, any way we can monkey wrench Lyndon Johnson’s peace initiative. What was significant about this was that Anna Chennault did approach the South Vietnamese; she was captured by U.S. intelligence agencies. Lyndon Johnson knew about this, he wanted to blow the whistle on Nixon, but there was never any confirmation that these words actually came out of of Nixon’s mouth. So now, this last piece of the puzzle is in place and we can say that Nixon not only knew about it or countenanced it, but he actually directed it.

4:08 Blackmon: Let’s fill out the scene a little bit. [Farrell: Sure.] It’s 1968, the Vietnam War has been raging, opposition to the war is surging, LBJ has decided not to—pulled back from running for reelection, largely because of what seemed to be out of control protests against the Vietnam War. Anna Chennault is originally a Chinese national, but a sort of Chiang Kai-shek, earlier era Chinese national, who married an American general, am I remember correctly?

FACTOID: February 1968 Gallup poll: 35% liked LBJ’s handling of war, 50% disliked

Farrell: Yes.

Blackmon: A World War II era general.

Farrell: The hero of the Flying Tigers.

Blackmon: And so is this sort of a grand dame of a certain kind of political constituency in Washington, very busy and conservative circles. So how does she, how does this rather dramatic sounding figure, how does she come into the Nixon scene at all?

Farrell: Well, Nixon was a fierce anticommunist from the time he was in the House of Representatives and then the Senate, and then of course was vice president when he got well-known for his redbaiting.

FACTOID: Nixon had been Representative, U.S. Senator, vice president to Eisenhower

Anna was a member of good standing in what was called the China Lobby, which was the Taiwanese, free China, interest in Washington. She became a big fundraiser for Nixon and as you said, Lyndon Johnson very desperately wanted to end the war that fall because he wanted that to be part of his legacy, he didn’t want it to drag on. The Soviets got in contact with him, and there’s an amazing number of coincidences with this story and the story of last fall’s alleged bugging, or proven bugging, of the DNC. The Soviets got in contact with Lyndon Johnson and they said we would like Humphrey to get elected, we will pressure the North Vietnamese to enter “productive talks,” that’s the phrase that they used, and Johnson raised—his hopes were soaring. On the Nixon side, we now know that he directed it. We don’t know for sure, whether he was just reacting to what he thought was another Democratic dirty trick, or whether he had deeper motives about actually stalling the talks because he disagreed with them on policy reasons. The notes are kind of ambiguous in that regard, but very clearly, he says this to Haldeman. Johnson calls him up and there’s this wonderful conversation on the Miller Center website, where they’re talking about this and Nixon denies it.

Sound on Tape with text overlay:

President Johnson: Hello?

Richard Nixon: Mr. President?

President Johnson: Yes.

Richard Nixon: This is Dick Nixon.

President Johnson: Yes, Dick.

Richard Nixon: I just wanted you to know that I got a report from Everett Dirksen with regard to your call. And I just went on Meet the Press and I said that—on Meet the Press—that I had given you my personal assurance that I would do everything possible to cooperate both before the election, and if elected, after the election. And that if you felt, the Secretary of State felt, that anything would be useful that I could do, that I would do it. That I felt Hanoi—I felt that Saigon should come to the conference table, that I would—if you felt it was necessary—go there, or go to Paris, anything you wanted. I just wanted you to know that I feel very, very strongly about this, and any rumblings around about somebody trying to sabotage the Saigon's government's attitude there certainly have no—absolutely no credibility as far as I'm concerned.

Farrell: Nixon denies it again to David Frost, in the famous Frost-Nixon interview. So, he had built this sort of wall of deniability around it, until this latest piece. It’s like when you go on vacation to the beach and for rainy days, you spread out a jigsaw puzzle and as you walk by it, every once in a while you do a corner or you find a couple of pieces, and that’s, I’m finding out, that that’s how history is sometimes put together.

FACTOID: Frost Interview: Largest political interview audience in history

7:52 Blackmon: So I printed out one of the pages of notes that you found and that you include in the book, and this is in Haldeman’s handwriting. And so he says, “Keep Anna Chennault working on SVN,” and that’s South Vietnam. [Farrell: South Vietnam.] South Vietnam. And then it particularly makes reference to on the three Johnson conditions. [Farrell: Right.] And so what’s that referring to and—why is it that the other parties? We can see why Nixon, for this very cynical reason, wants to keep the, prevent the war from coming to an immediate end, but what’s the leverage to the South Vietnamese?

Farrell: Right. Well, remember I was talking about Nixon’s motives. One of them obviously was to win the election, but he also had doubts or fears that American strategic position would be undermined by what he feared would be a sellout. So, when he talks about the three Johnson conditions, is that Johnson had laid down, in a public speech, three different conditions that the North Vietnamese would have to meet before they engaged in peace talks with the United States, and in that process over this time, all three conditions were met, unbeknownst maybe to Nixon, and so there really was only one reason why the South Vietnamese didn’t go, and Anna Chennault was captured by American eavesdroppers, telling the South Vietnamese ambassador, hold on, we’re going to win, you’ll get a better deal after election day. But one thing you do get to realize as you read Haldeman’s notes over time, is he has this pattern of writing next to him, so you can see the different letters of where the orders come from, and then he puts a check when the order is carried out. He was a very, very thorough man. And I checked this with John Dean, who was one of the White House veterans who is still around, you know he confirmed to me what I had come to believe, by looking at all these notes over the years, that this meant that this had been done, it wasn’t just Nixon spouting off as he was wanting to do.

9:45 Blackmon: So this little notation right here is telling us that this is an order, a directive from Richard Nixon?

Farrell: Yeah, yeah.

Blackmon: And then the checkmarks as it’s done.

Farrell: And he has—there’s an exclamation point, and so yeah.

10:00 Blackmon: Now there’s another note that you found, which there’s reference to, “any other way to monkey wrench it,” and this term to monkey wrench the talks. Is it possible that monkey wrench could have meant something other than this?

Farrell: Sure. First of all, these are notes taken by Haldeman, so they’re fragmentary in any case, but monkey wrenching, I took to mean was monkey wrench the peace initiative. Whether or not Nixon’s motives were just politically stop it, or actually stop the peace talks, you could make the argument, well he’s just talking about monkey wrenching the political side of it and not actually monkey wrenching the peace talks, but they’re so closely intertwined that you really are picking at straws there if you’re trying to make that argument.

10:44 Blackmon: Now Ken Hughes, who you mentioned, another scholar on all this, he has postulated the idea that this is actually the beginnings of Watergate, that after Nixon is elected president, that because of these conversations, he’s convinced there’s a file at the Democratic National Committee offices, that contains the proof of this, and that the reason the plumbers are sent in, is to get that toxic file so that it can’t be used against Nixon. Does that make sense to you?

Farrell: Yeah, the tapes are very suggestive, they’re not—we still need one more piece of the puzzle that more specifically says what Nixon means when he talks about the bombing halt.

FACTOID: Listen to Nixon White House tapes at millercenter.org/the-presidency

He had a way of getting these little catch phrases that collectively covered a wide range of things and could have meant the Chennault affair, it could have just meant they have a file about Johnson’s wiretapping, that we may want to get and we may want to use against Johnson, and in fact he says that on one tape. But I think Ken’s theory is pretty sound.

11:43 Blackmon: And we’re not talking about a trivial development. There’s no way for us to know for sure, that the war would have ended in 1968 or ’69, but it is the case that between the time of these events and when the last American troops are removed from Saigon, there’s another 20,000. American casualties. [Farrell: No, deaths.] Deaths, 20,000 American lives that are lost.

FACTOID: April 1975, U.S. abandons Saigon, evacuates thousands of civilians

Farrell: And also, millions of Asians. This brings into play, if the war had been stopped then, you wouldn’t have had the Cambodian invasion, you might not have had the Cambodian genocide, you might not have had the South Vietnamese boat people and all the people that were lost in the fall of Saigon. So there’s lots of big stakes. It’s a series of hopping on stones across a stream to get there, but what I can say for sure is that Lyndon Johnson and his advisors believed, in October, 1968, that there was a peace deal that they could strike before he left office, and it was not a political trick like Nixon suspected, just to get Humphrey elected. They really believed that they had peace at hand.

12:50 Blackmon: You write in the book, “It is hard not to conclude that of all of Richard Nixon’s actions, in a lifetime of politics, this was the most reprehensible.”

Farrell: Yeah. Given what we learn later, from the Church Committee and other investigations in the later ‘70s, about the sins of previous presidents, regarding burglary and wiretapping and assassinations of foreign leaders, Nixon’s actions in Watergate actually become somewhat more acceptable.

FACTOID: U.S. Senate’s “Church Committee” probed CIA, NSA, FBI, and IRS There’s an argument. [Blackmon: At least.] Yeah. There’s an argument there that he was a victim of a double standard, but this one is different, because this one is saying yeah, we’re going to meddle with a peace process that could end widespread suffering, that could cost us thousands of lives, American lives as well as thousands of Vietnamese lives as well, and Cambodian lives as well.

13:42 Blackmon: How is it that these notes went undetected as long as all this?

Farrell: Nixon was a very unique case. Because of Watergate, when he left office, the Federal Government seized his papers and his tapes, and they did not go with him to San Clemente, they did not go with him to a presidential library immediately, and he engaged in this long litigation, like I said, for ten, fifteen, twenty years, spent $2 million in legal fees to try to secure what he could. These were part of his political papers, and so they went to the foundation and the foundation kept them after he died.

FACTOID: Read Nixon papers at nixonlibrary.gov/virtuallibrary

Over time, we’re liable to have a lot more National Security Agency memos, or cables, from their eavesdropping of what was going on in Saigon, and that’s liable to show us that this had no effect on Thieu whatsoever, that it was all internal politics that made him continue. And certainly, the North Vietnamese and the South Vietnamese showed, in the next four years, that they were incredibly stubborn about coming to terms on a peace deal. Again, I don’t think because you want to argue that no great opportunity was lost, doesn’t mean that what Nixon did was right or that it didn’t happen. It did happen and what he did was wrong, and that’s why I think it’s reprehensible, because he put his own political success ahead of what in the end turned out to be a very great loss of life.

15:08 Blackmon: What’s the likelihood that thirty years from now, that things surface, and we look back on this time and it turns out that whether it’s those things I’m referencing or other ones, how much confidence can we ever have that we actually know the reality of anything that appears to be certain in our politics in the present?

Farrell: Umm, I think that it’s going to be more difficult for scholars of this period, because after Watergate, there was no more tapes, after Iran Contra, there were no more presidential diaries. We’re down to emails and we saw what happened to emails in the Bush administration and the Hillary Clinton campaign. Basically, you’re talking about very, very guarded White House staffs, having seen all this age of scandal behind them, being very careful about what they collect, and I think it is going to be very hard. I think people like Bob Woodward, when they go in with their tape recorder and they get everybody to talk for hours, are going to be invaluable resources. I think Tweets and emails will be invaluable resources, but they can be erased and made to disappear.

FACTOID: Woodward has 18 books, latest is The Last of the President’s Men

16:20 Blackmon: The book is about much more than just that, that one incident. In terms of the broader depiction, a couple of reviews from other folks, one John Coyne, Washington Times, saying—former Nixon speechwriter, said that you’ve got an overemphasis on the dark side. The same time period, not long ago, a review in the New York Times said, “Some readers may find Farrell’s portrait too sympathetic.” Can both of those things be true at the same time?

Farrell: I think, paradoxically, I think that they can. I think that Nixon was a guy that attracted great loyalties from those who worked for him, it was amazing. It was one of the first things that struck me as I began to talk to them, was how protective they were of this poor guy who had so many personal problems and his peculiarities, and they believed they saw him as a tragic figure who was treated unfairly by the press and by history. So right away, you begin to develop some sympathy and some empathy for Nixon, and many of the things that have been said about him over time, by liberal journalists and scholars are flat out wrong, so that can be why…

Blackmon: What do you mean by that?

Farrell: Well, for example there’s the shorthand for Nixon’s experience in World War II was that he spent the wat playing poker. Well he did spend a lot of time playing poker, but he happened to spend it in the Solomon Islands, in a combat zone, playing poker, which is a different thing entirely. There was a famous controversy about whether, in this first election for Congress, there were phone calls made by the Republican Party on election eve, saying you know that Jerry Voorhis, who was his opponent, you know that Jerry Voorhis is communist. Well, you know, there are enough people that say that happened, that there probably were some phone calls made, and yet it was blamed on Nixon and Nixon’s organization, that they must have had a massive—with phone banks everywhere throughout the district, and that this is what swung the election. Well no, what swung the election was Nixon’s great performance in a candidate debate. So there’s things like that, that as you correct the record then people say okay, well you’re going out of your way to being too nice to him.

FACTOID: Nixon won 56% of vote in 1946 to beat 5-term Rep. Jerry Voorhis (D)

Once you get into the tapes and you start quoting the tapes, it’s impossible not to reveal the dark side. This is a very twisted human being. Richard Nixon came back from his greatest triumph, opening China, and he’s caught on the tape, sitting there with Henry Kissinger saying, “You know Henry, it all means nothing, the American people are a bunch of sheep. They look at that picture of me shaking hands with Mao and think it means something and it really doesn’t, it’s all about power politics.” This was all just to get reelected. Nixon, at his most cynical, bad-mouthing his greatest accomplishment, and you find that time and time again. The tapes are going to be an immeasurable resource for scholars as they pore over, and more and more, the excerpted national security and personal stuff becomes available to them, for another fifty years, there is just this amazing resource. Imagine if you had tapes of Jefferson and Hamilton going at it in front of George Washington, over forgiving the revolutionary debt.

FACTOID: Listen to Nixon White House tapes at millercenter.org/the-presidency

19:44 Blackmon: That sounds like a musical.

Farrell: And don’t think I didn’t think of that when it was happening. Even as a Jeffersonian, I sat there flinching at some of the portrayals of T.J. but um, to get back to the question is that yes, this is a man who had a good side and he had a bad side, he had a light side and he had a dark side. He was a very fascinating individual. He had this tragic flaw. He was afraid of things that would bring about his downfall, and as Henry Kissinger said, “It was like a Greek tragedy, where he went out and did the things that were guaranteed to bring about the result that he most feared.” So you can be both light and dark on it, I think.

20:25 Blackmon: In the book, along these lines, there’s a passage from a tape that I wasn’t familiar with, that from December 14, 1972, you quoted as never forget—this is Nixon.

Sound on tape with text overlay:

“The press is the enemy, the press is the enemy, the press is the enemy, the establishment is the enemy, the professors are the enemy. Professors are the enemy, write that on a blackboard 100 times and never forget it.”

Farrell: That was one month after her won the biggest landslide in American history. The man was just an unhappy individual, could not bring himself around. It was also while he was contemplating the Christmas bombing of Hanoi, to savagely bring an end to the war, and he was also contemplating the fact that the Watergate cover-up was beginning to fray. So he was under a lot of pressure and that’s why that came out, but I think it really shows just his total inability to accept his own accomplishments.

20:27 Blackmon: I’m always a little skeptical of any comparisons between historical figures, and this press is the enemy quote is reminiscent of, but though to be fair to President Trump, he didn’t say the press is the enemy. He named some specific members of the mainstream media, though later he added some conservative media outlets as well.

Farrell: But he also took it further. He said the press is the enemy of the American people.

Blackmon: Of the people, right, exactly.

Farrell: Which Nixon never said.

21:48 Blackmon: So, as far as this comparison, and one of these reviews, the New York Times, that I referred to a moment ago says, “The similarities between Nixon and Trump leap off the page like crickets.” That’s a new expression to me, like crickets. Similar, suggests in a boring way perhaps, but what do you make of the Trump-Nixon comparison?

Farrell: There’s a vast number of coincidences. We’ve had massive protests, we’ve had allegations of eavesdropping, we’ve had a scandal involving a break-in at the DNC, we’ve had the press is the enemy, we’ve had ridicule of a press secretary. The biggest difference is that it’s a Republican controlled Congress. Nixon faced a Democratic controlled Congress that was quite ready to launch. Tip O’Neill and Ted Kennedy were quite ready to launch an impeachment investigation of Nixon. So that’s a big difference.

Personally, they have the same sort of runaway presidential id; Nixon on the tapes and Trump on the Tweets. There’s a lot of echoes there that I hear. As individuals, very different personalities. You know, Trump was born into a rich family. There’s evidence of coldness in his childhood but it was a comfortable childhood. Nixon had a Dickensian childhood, with two brothers dying and the family’s finances, on a rollercoaster throughout his childhood. Famously, he couldn’t go to the Ivy League, because his family couldn’t afford to pay the transportation to the East Coast, or to board him while he went to Yale or Harvard. A part of that whole, the press is the enemy, the professors are the enemy, the establishment is the enemy, comes from the feelings of resentment that these things were taken from him and that better educated richer people like JFK, had everything given to them, and Nixon had to scrap for it basically alone, all his life. So there’s that difference as well.

FACTOID: Nixon went to Whittier College then Duke Law on scholarship

But Nixon read books, Trump famously doesn’t read books. Nixon wrote books, he was a genuine foreign policy intellectual.

FACTOID: Nixon’s last book Beyond Peace published in 1994, after his death

In his wilderness years, between losing in ’60 and ’62, and then coming back in ’68, Richard Nixon was reading Machiavelli and he was treating himself to the great philosophers of old. I don’t see Trump doing that. Nixon very famously refused to play golf when he was president, because it took too much time.

24:24 Blackmon: I like the idea of ending our conversation with an endorsement of an attribute of President Nixon. Thanks for being here. We hope you’ll join us for future editions of American Forum, where our focus is always on the presidency and the challenges that face the nation. You’ve heard a lot today, about the Nixon tapes. The Miller Center is the place on the Internet that you can actually listen to them. There are about 3,400 hours of Nixon White House tapes, once the property of the former president, they now belong to the U.S. Government and to you, the American people, following numerous legal battles that began with the famous 1974 Supreme Court case, U.S. v. Nixon. The Miller Center has published over 200 highly detailed, heavily researched transcripts from those recordings. To listen to those tapes, go to our new website, millercenter.org, click on “The Presidency”, and then click on Secrete White House Tapes.” You will also find extraordinary conversations from the administrations of Lyndon Johnson and John F. Kennedy. You can watch American Forum on your local PBS affiliate, or to join our ongoing conversation, look for us on the Miller Center Facebook page, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @douglasblackmon. Jack Farrell is complicated, read along with me on the screen, @jaloysius, his first initial and his middle name. See you next week.