Censured but not impeached

Whigs in the Senate had a problem with Andrew Jackson—but Democrats controlled the House

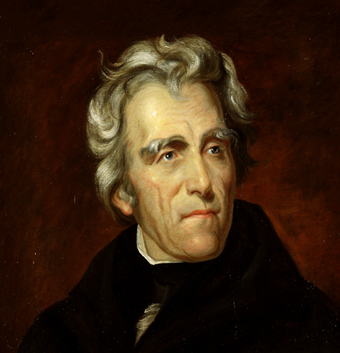

A fiery patriot and a strident partisan, Andrew Jackson left his stamp on American democracy in the form of a two-party system. Under his leadership, the Democratic party became the nation's most durable and successful political party. But Jacksonian democracy did not emerge without conflict.

Jackson defined himself not by working to enact legislation but by thwarting it. He cast himself as the people's tribune, their sole defender against special interests and their minions in Congress, and he vetoed more bills than all six of his predecessors combined. He forged direct links with the voters using plain and powerful language in official messages. And he dominated his cabinet, forcing out members who would not execute his commands.

Plunged into this dynamic environment was the Bank of the United States, a quasi-public corporation chartered by Congress to manage the government's finances and provide a sound national currency. At the urging of Alexander Hamilton, the original Bank of the U.S. was chartered in 1791 for a period of 20 years, but the opposition Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans allowed the charter to expire. Financial difficulties following the War of 1812 led Congress to found a second Bank of the United States for another 20 years beginning in 1816, and after a rocky, start the Bank had ceased to be controversial.

Jackson thought otherwise. Surprising even his own supporters, he attacked the institution in his very first message to Congress in 1829 and never let up. As Jefferson and his followers had maintained, Jackson believed the Bank unconstitutional, its concentrated financial power a threat to liberty. Vetoing a bill to recharter the bank, he said, “It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes.”

Jackson thought otherwise. Surprising even his own supporters, he attacked the institution in his very first message to Congress in 1829 and never let up. As Jefferson and his followers had maintained, Jackson believed the Bank unconstitutional, its concentrated financial power a threat to liberty. Vetoing a bill to recharter the bank, he said, “It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes.”

The move led to a showdown with the Senate.

Nonetheless, the Bank's charter was not scheduled to expire until 1836. Lacking votes to revoke it, Jackson decided to withdraw all government deposits and place the funds in selected state-chartered banks. The move led to a showdown with the Senate.

The Bank's charter gave the secretary of the treasury, not the president, the authority to move the deposits, with the additional condition that he had to explain his reasons to Congress, where the House had just voted overwhelmingly to keep the funds where they were. When Treasure Secretary Willian John Duane refused to do Jackson's bidding, the president fired him, and installed the sympathetic Roger Taney in his place. By the time Congress convened in December 1833, the process was nearly complete.

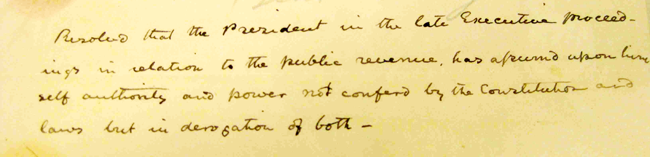

This maneuvering outraged many in Congress. The president's political foes, the new Whig party—namesake of the revolutionary era anti-royalist party in Britain and America—determined to fight back against this abrogation of legislative power. They rejected Jackson's nominees for government directors of the Bank of the United States, rejected Taney as secretary of the treasury, and in March 1834, adopted a resolution of censure against Jackson himself for assuming "authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both."

For the president, the move reeked of impeachment, but without the Constitutional process:

The resolution, then, was in substance an impeachment of the President, and in its passage amounts to a declaration by a majority of the Senate that he is guilty of an impeachable offense. As such it is spread upon the journals of the Senate, published to the nation and to the world, made part of our enduring archives, and incorporated in the history of the age.

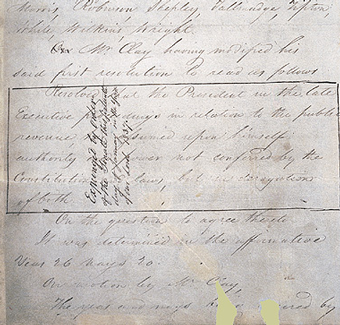

That history, as it turns out, lasted less than 3 years. In January 1837, Democrats, back in control of the Senate, voted to expunge the censure resolution, writing across the original record, “Expunged by order of the Senate this Sixteenth day of January in the year of our Lord, 1837.”