Partisanship, Polarization, and the Administrative State

The presidency itself has become a polarizing institution

President Joseph Biden would seem to be on a roll as the 2024 presidential campaign approaches. Inflation has dropped from 9.3 percent to 3 percent. Unemployment is at 3.5 percent, a half-century low. These positive indicators, the White House claims, can be attributed to two years of successful legislation: a generous COVID-19 relief package, a bipartisan infrastructure bill, a bipartisan measure to boost the domestic semiconductor industry, and the first major legislation to combat climate change. Still, President Biden’s poll numbers remain low—a July 2023 survey logged his approval at just 39 percent.1

Bitter partisan conflict has persistently dogged Biden’s approval ratings. While that same poll showed that 74 percent of Democrats approved of Biden’s performance, only 5 percent of Republicans did. Biden is not just the victim. Although he has positioned himself as the ballast against his party’s left wing, he has nonetheless been drawn into—and contributed to—the partisan wars. As he boasted in the first debate with Donald Trump during the 2020 campaign, “I am the Democratic Party right now.”

That phrase gave voice to a powerful feature of contemporary American politics—presidents are the repository of party responsibility.

That phrase gave voice to a powerful feature of contemporary American politics—presidents are the repository of party responsibility. In fact, from the start of Biden’s presidency, he has at times embraced the combustible combination of executive prerogative and partisanship that has roiled the country since the late 1960s.

Biden has demonstrated just how deeply “executive-centered partisanship” is rooted in American politics. Both Democrats and Republicans depend on presidential candidates and presidents to pronounce party doctrine, raise campaign funds, campaign on behalf of their partisan brethren, mobilize grassroots support, and advance party programs through administrative action (and court appointments). To understand how Joe Biden—the embodiment of the professional, pragmatic politician—has become the target of the rallying cry, “Let’s Go Brandon” (a conservative code for a vulgar slogan, “F— Joe Biden”), we must see how the office of the presidency itself has become a polarizing institution.2

The rise of executive-centered partisanship

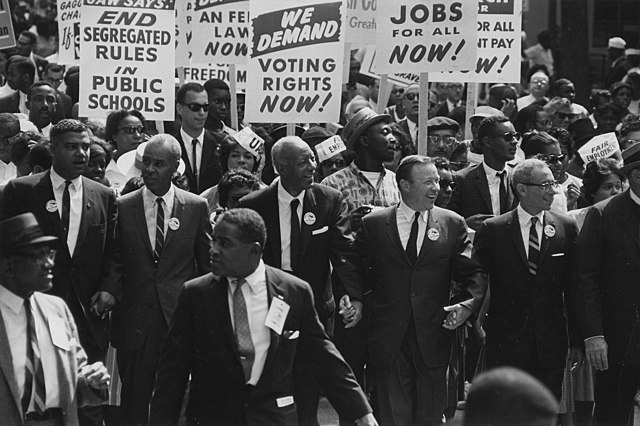

Presidential partisanship sits at the cross-currents of two related developments. First, organizational and electoral reforms weakened the decentralized, patronage-based parties that dominated most of the 19th century. Throughout the 20th century, insurgent movements pressured both political parties to alter the rules governing their presidential nomination processes. Party leaders were removed as guardians of national party conventions, with power shifting to “the people” in selecting candidates for office and in determining party priorities through direct primaries and open caucuses. This shift accelerated in the 1960s, propelled by civil rights and antiwar activists, culminating in the McGovern-Fraser reforms of the early 1970s. Republicans quickly followed suit.

“Participatory democracy” did not empower the median voter—the target of pragmatic parties seeking national consensus.

“Participatory democracy” did not empower the median voter—the target of pragmatic parties seeking national consensus. The weakening of traditional party organizations enhanced the influence of donors, interest groups, and social activists who scorned the pragmatic politics and compromise that, historically, had been credited with forging majority coalitions in the United States.3 In other words, reforms empowered the so-called party bases—the most militant and ideological voters.

A second development enhanced the impact of reforms: the growth of executive prerogative. This development blossomed during Franklin Roosevelt’s long presidency. Roosevelt created the Executive Office of the President through the Reorganization Act of 1939. That organic statute of the modern presidency established the White House Office (the West Wing) and important staff agencies like the Office of Management and Budget. This structure allowed the president to form alliances with activists and outside groups who disdained the party “establishment.” The joining of executive prerogative and partisanship subordinated decentralized and pluralistic party coalitions to more national and programmatic networks.

These two developments, combined, have led to a national struggle for American identity that reverberates powerfully through our own time. Battles over who belongs to the sovereign have disrupted the United States since the beginning of the republic. But the cataclysmic 1960s, especially the civil rights revolution and the right-wing counterrevolution that sought to erase it, transformed what was once episodic and regional into a national norm.

Since then, progressive and conservative movement activists . . . have pulled the parties away from the center, fueling ideological polarization and legislative stalemate.

Since then, progressive and conservative movement activists—especially civil rights activists on the Left and the Christian Right on the Right—have pulled the parties away from the center, fueling ideological polarization and legislative stalemate. Organized interests and movement activists increasingly privileged executive action to further their aims. Consequently, presidents of both parties have sought to achieve their policy objectives and appeal to their party base using administrative powers rather than navigating a complex system of separated powers to pass legislation.

No single president is responsible for the rise of executive-centered partisanship.

No single president is responsible for the rise of executive-centered partisanship. Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump all contributed to make this an entrenched feature of the modern presidency.

The policy consequences of executive-centered partisanship

The presidency’s ever-strengthening ties to partisan concerns have real-world consequences. Both parties view national administration as a weapon for their party’s objectives. Liberals have sought to build administrative capacity to design and implement social welfare policies. Despite rhetorical appeals for “limited government,” since the late 1960s, conservatives have also sought national administrative power as ardently as liberals, connecting to partisan goals of enhancing national defense, homeland security, border protection, and local policing and establishing market-oriented policies in education, climate change, and government service.

The partisan battle for the soul of the administrative state plays out in many venues, but two significant battlegrounds are worth noting.

First, facing partisan gridlock in Congress, presidents of both parties have come to rely on unilateral powers to make policy.

First, facing partisan gridlock in Congress, presidents of both parties have come to rely on unilateral powers to make policy. Executive orders make legal changes but do so without invoking oversight from the other branches—or the other party. This makes them especially attractive venues for partisan policy objectives. Upon taking office, President Obama issued an executive order to close the controversial Guantanamo Bay detention center within one year. His administration failed to implement the order, and President Trump later issued another order to keep the facility open indefinitely. This unilateral—and partisan—flip-flop has become par for the course across a range of issues. Indeed, incoming presidents now expect on their first day in office to issue a flurry of executive orders undoing an opposing-party predecessor’s more partisan executive actions.

Executive agreements and presidential memoranda are less visible than executive orders and undergo a less rigorous internal clearance process.4 But they are not necessarily less consequential or less partisan. President Obama’s signature immigration policy action—Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)—was accomplished via an executive memorandum.5 Donald Trump, likewise, rescinded those efforts.

These executive measures can also be subject to the aforementioned partisan flip-flop. President Reagan’s “Mexico City Policy,” a 1984 presidential memorandum that prohibited U.S. foreign-aid dollars from being used to support abortions, has ping-ponged back and forth across presidencies—Democratic presidents revoke it, and Republican presidents reinstate it.

Second, executive-centered partisanship drives presidents to refashion and politicize the federal bureaucracy.

Second, executive-centered partisanship drives presidents to refashion and politicize the federal bureaucracy, transforming national service into a vanguard of partisan objectives. This plays out in at least two ways. First, presidents have too often selected appointees based on ideological purity rather than administrative prowess or competence. Second, the reliance on political appointees has often meant increasing the budget and personnel of the president’s favored agencies, helping drive highly partisan policy agendas.

Recently, conservatives have advanced a novel constitutional doctrine of the unitary executive, which holds that the Constitution gives the president power over and above any act of Congress that might delegate authority to a specific cabinet agency.6 This development has the potential to subvert the career bureaucracy’s foundational mission: neutral competence.7 The Trump administration showcased the possibilities of this doctrine, deploying unilateral executive action to achieve partisan objectives on issues such as environmental protection and immigration. Rather than building broad coalitions to reform the federal agencies responsible for those policy areas, the administration governed with extreme skepticism of the “Deep State.”

Emblematic of these efforts was Trump’s “Schedule F” executive order, a unilateral action that would have removed employment protections from career employees, converting an entire class of civil servant positions into political appointments. Biden rescinded Trump’s Schedule F executive order, but Trump and other leading Republican candidates have vowed to immediately restore it if elected to the White House in 2024.

The future of executive-centered partisanship

Where does executive-centered partisanship leave a country that is already starkly bifurcated along partisan lines?

In the immediate term, the executive action flip-flop has meant a lack of policy continuity. This instability impedes firms and other regulated parties from planning for the future. Although largely unmeasured, it has deleterious effects on market growth and competent administration.

The executive action flip-flop . . . has deleterious effects on market growth and competent administration.

Over a longer horizon, the partisan use of the federal bureaucracy has helped foster deep public skepticism about fair-minded public administration, afflicting conservatives and liberals alike. Conservatives denounce the Deep State as a system rigged against “the people.” Liberals fetishize strict adherence to complex procedures as a way to hold the bureaucratic beast accountable.8 In turn, an emerging skepticism about administrative power rankles the judiciary, threatening the demise of judicial deference to federal agencies (as enshrined in the landmark Chevron doctrine; Chevron USA Inc. v. NRDC) and eliciting the rise of new judicial philosophies like the “major questions doctrine.”

Executive-centered partisanship is also linked to policy failures and ineffective government. As the executive’s responsibilities have grown, so has the size and scope of government failure.9 Although Democrats and Republicans ostensibly differ on government’s purposes, presidents of both parties use administrative means to accomplish their desired partisan ends. But while both parties are quick to turn to the bureaucracy, neither is willing to meaningfully invest in its overall effectiveness or efficiency.10 The result is an administrative state that is bogged down in procedure, plagued by outdated technologies, and ineffective regulations, understaffed, heavily outsourced, and riddled with vacancies in leadership positions.11

In conclusion, the presidency has not avoided the partisan polarization that fractures the nation. Rather, in many ways, it is the centerpiece of that polarization. Joe Biden was not wrong; he is the Democratic Party right now. And therein lies the problem.

Endnotes

Peter Baker, “A Rising Tide Lifts Many Boats, but So Far Not Biden’s,” New York Times, August 4, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/04/us/politics/biden-approval-rating.html.

Colleen Long, “How ‘Let’s Go Brandon’ Became Code for Insulting Joe Biden,” AP News, October 31, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/lets-go-brandon-what-does-it-mean-republicans-joe-biden-ab13db212067928455a3dba07756a160.

Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, How Democracies Die (New York: Crown, 2018).

See, e.g., Jack L. Goldsmith, Curtis A. Bradley, and Oona A. Hathaway, “The Failed Transparency Regime for Executive Agreements: An Empirical and Normative Analysis,” Harvard Law Review 134 (2020): 629; Kenneth S. Lowande, “The Contemporary Presidency: After the Orders: Presidential Memoranda and Unilateral Action.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2014): 724–41.

Janet Napolitano, “Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion with Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as Children” (memorandum), Department of Homeland Security, June 15, 2012, https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/s1-exercising-prosecutorial-discretion-individuals-who-came-to-us-as-children.pdf.

Stephen Skowronek, John A. Dearborn, and Desmond S. King, Phantoms of a Beleaguered Republic: The Deep State and the Unitary Executive (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021).

Herbert Kaufman, “Emerging Conflicts in the Doctrines of Public Administration,” American Political Science Review 40, no. 4 (1956): 1057–73.

Nicholas Bagley, “The Procedure Fetish,” Michigan Law Review 118, no. 3 (2019): 345–401.

William G. Howell and Terry M. Moe, Presidents, Populism, and the Crisis of Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020).

Nicholas R. Bednar and David E. Lewis, “Presidential Investment in the Administrative State,” American Political Science Review (2023): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000114.

Bagley, “Procedure Fetish”; Jennifer Pahlka, Recoding America (New York: Macmillan, 2023).