About this episode

November 14, 2016

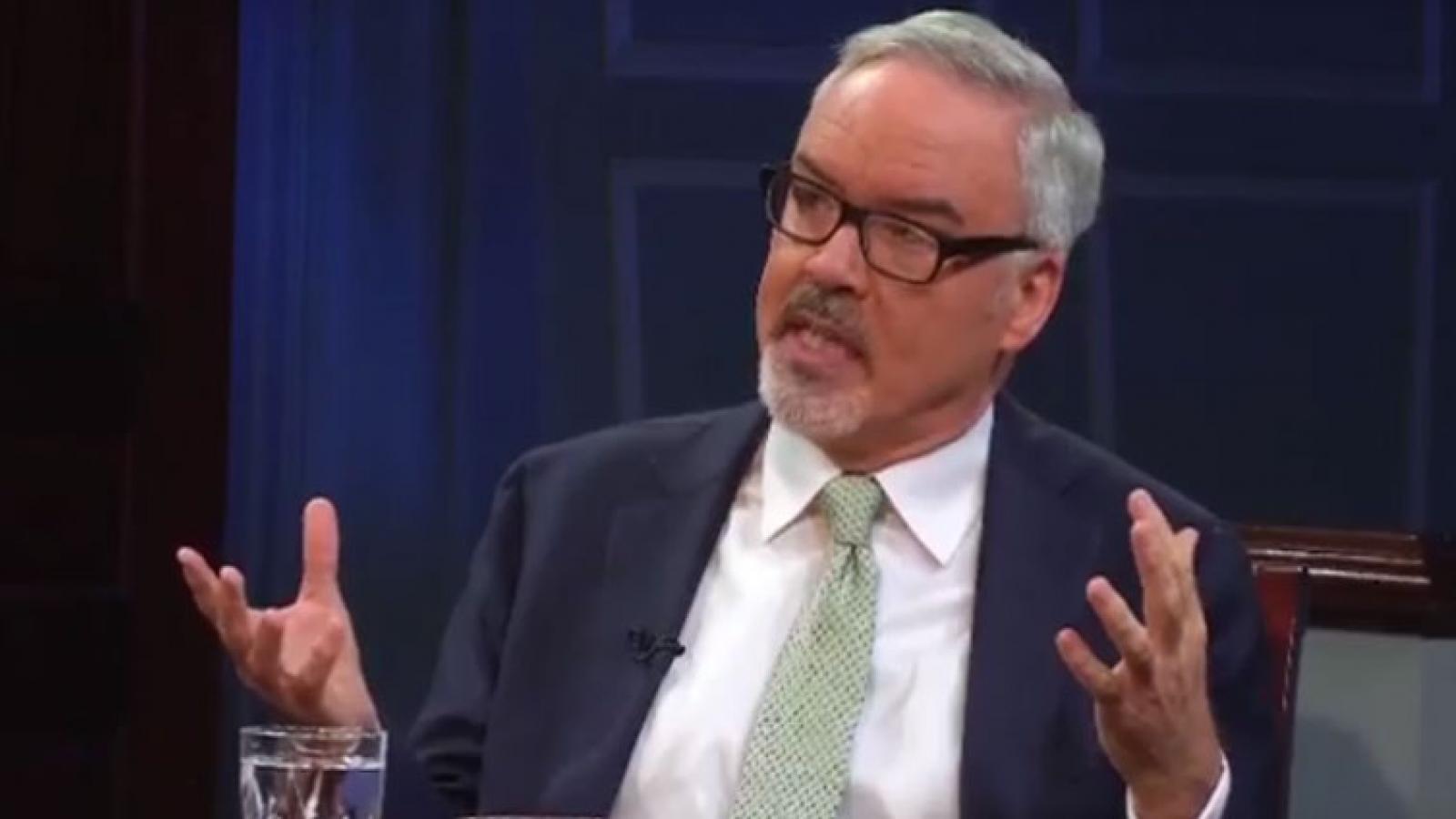

Thomas J. Sugrue

The transition from one president to the next is generally not a gripping drama. But this year—as with the often astonishing campaign that preceded it—Americans are watching the Trump transition very closely. Our guest is an extraordinary observer of these crucial moments. Thomas Sugrue is a historian and a professor of social and cultural analysis at New York University.

The Presidency

The first days of a great presidency

Transcript

0:52 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum, I’m Doug Blackmon. The transition from one President to the next in most election years is not a particularly gripping drama for the American people. New presidents such as Donald Trump must staff the White House, fill out a cabinet and eventually name about 4,000 appointees throughout the federal government. In most years, few citizens ever even absorb many names of the most influential voices around the President. But this year—like the often astonishing campaign season that preceded it—Americans are watching president-elect Trump and his transition like an NFL team getting ready for its first ever Super Bowl—a very unconventional Super Bowl, at that. Already, the new president has signaled that he is trying to make peace, at least to some degree, with traditional Republicans and people who didn’t vote for him. But he’s also making clear that the Trump administration will include some of the most controversial members of his campaign team, and won’t be abandoning some of the issues that many found so divisive over the past year. Our guest in this episode is an extraordinary student of these crucial moments in American history. Thomas Sugrue is an historian and a professor of social and cultural analysis at New York University, where he specializes in twentieth-century American politics, urban history, civil rights, and race. He’s a frequent commentator in the mainstream media (whether that’s good or bad) and has contributed often to the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, The Nation, Salon, and many other publications. Professor Sugrue is also the author of several books, most recently, Not Even Past: Barack Obama and the Burden of Race. Thank you for joining us.

Thomas Sugrue: Thank you Doug, it’s great to be here.

Blackmon: So we’ve just had this election that ended in a very different way than many people were expecting but also in a way that many Americans hoped for, ah, as it turns out.

FACTOID: Pew: 82% OF Democrats give Trump a “very cold” rating

And even more Americans hoped not for but nonetheless. We’ve just come to the end of this remarkable election year. Let’s start getting a sense from you of what the election of Donald Trump means in terms of how we will now remember the presidency of Barack Obama.

FACTOID: The Question: What does Trump’s victory do to the Obama legacy?

Now in your book, not even past, you talked about this as a truly, ah, ah, milestone event in American political history, but also warned that while it looked like the arrival of a post-racial era that there remained deep divisions around race in America. But what’s your sense? What does this do to our memory of Barack Obama.

Sugrue: Well I think it’s too early to know how a Trump presidency will change our appraisal of an Obama administration. It’s tempting to project back ah, ah, an apocal change to Obama’s administration and to suggest that Trump is going to unravel it, undo it, ah make something entirely different in Washington. And what we know from lots of political scientists and political historians is the ship of states is hard to turn. Obama positioned himself as a transformative president. As someone who would really undo ah, years of polarization with bipartisanship would transform the culture of Washington by bringing in experts and who are detached from the messy nitty gritty of every day politics, who would heal America’s racial and political and religious and cultural divisions. Yet making those changes prove to be a lot more difficult for Obama. Likewise, Trump is promising to undue much of the Obama administration’s legacy. Ah, to address problems that remain unaddressed economically. He’s promised to challenge America’s immigration policy. But making changes given the nature of Congress and the nature of bureaucracy, the limitations of the president has with fundamental ways in the White House, the legacy of his predecessors means that it’s unclear how quickly and undramatically Trump will be able to accomplish the changes that he promised on the campaign trail.

5:08 Blackmon: Yea, it strikes me as a, really notable that in some of trump’s first remarks after the election when he first began to talk about some of the policies and more specifically what they might mean. Ah when he first came out and publically said, for instance, about the Affordable Care Act that, oh actually there may be some elements of it that should remain, the most popular parts. And I was taken back to President Obama saying unwittingly not quite realizing the cudgel that he was handing to his opponents over the next seven years when he said you’ll get to keep your doctor. And he meant one thing by that but the mismatch between that one phrase and he meant one thing but then the experience as it turned out for others and I immediately wondered whether President Trump is already inadvertently offering up the things that we used to pound him for not quite doing what so many of his supporters thought he was going to do during the campaign. But, have you, I guess that’s a risk of every new president.

Sugrue: Every new president comes in having made a boat load of campaign promises. Some carefully recent and carefully thought out others off the cuff on the campaign trail. And the electorate often takes the off the cuff policy ideas just as seriously as those well developed. So with Obama you had someone who was arguably the most disciplined presidential candidate and president in modern American history. Someone who seldom went off script. Who was very focused in what he said and as a result was I think somewhat predictable in the direction that his policies took. With Donald Trump on the other hand you have someone who had not spent a lot of time thinking up policy proposals who spoke from the gut rather than from the head. Who could not be by even the most capacious definition of discipline to be called a disciplined candidate and who sometimes changed positions within the same speech. Ah, so the difference I think between Obama and Trump is that we don’t know exactly what to expect out of Trump which is why he could criticize the Affordable Care Act and then suggest that maybe part of it will survive or he could criticize immigration enforcement and call for the construction of the wall and say, well, maybe it’s not going to be a full wall. Maybe it’ll just be a fence in some places, right. So we don’t know exactly where he’s going to land but what his supporters heard and what they’re going to hold him to will I think umm, will pose some really interesting challenges for President Trump and his staff the first two years in office.

8:00 Blackmon: Let’s go back for a second to this question of what this means for the Obama legacy and I think you’re right that as is always the case we won’t know for a long time really how history remembers Barack Obama. Certainly in the long sweep of history one thing will never change and that is that being elected as the first African American president he will be, his election will be a red letter date in the history books, umm, forever really. That’s an absolute certainty. But in terms of the closer in time examination of him, it’s interesting to me that in some respects I would say Trump’s election validates the president’s caution about being too radical or pushing too hard on an agenda that might have been seen as specifically aimed at minorities or African Americans in particular, he got a lot of criticism as the administration, particularly in the last years of the administration a lot of African Americans were very critical of him not seeming to have voided the perceived as a black president. But what happened in this election would seem to suggest that had he pushed harder in those ways he might have run into much, even greater resistance than what he did. But what do you make of that reasoning?

Sugrue: I think that reasoning is right on the mark. Obama ran for the presidency amusing the rhetoric of reconciliation around racial issues and bipartisanship. That meant on the campaign trail he scarcely mentioned questions of race or of civil rights. When he did it was primarily to African American audiences. Umm and in his first term in office the political scientist, Daniel Gillion, at the University of Pennsylvania, said that Obama talked less about race than any of his predecessors before or beyond John F. Kennedy. So really quite extraordinary actually. The first African American president was the most silent in nearly 50 years on questions of race. But that’s because a mere mention of race by Obama, even the least controversial statement, often led to weeks of headlines. For example, when Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates was arrested on his front porch trying to get into his house and Obama used that as a moment off handedly to reflect on the history of police community tensions around African Americans. And that was news for a couple of weeks. He was accused of fermenting racial division, of hating white people at one point by one of his critics. Umm, and so Obama learned and knew that by discussing racial issues in a really public way he risked challenges to legitimacy of his presidency. But on one hand on the other side many of Obama’s critics assumed that because he was African American he was going to be more radical. He was going to be an outsider. He was somehow tainted by foreign ideologies. He was maybe not born in the United States. Maybe a Muslim. Maybe a Socialist. And while Obama himself continually discounted the affect of those kinds of conspiracy theories about his background on himself, it’s clear that a lot of the opposition to Obama drew from that kind of poisonous well of thinking that he was a dangerous racial outsider. And, you know, Donald Trump making birthism one of his kind of entry points into the national political stage played to that really vile, steamy, underside to American politics. But look, I mean there’s also umm, legitimate ideological and political differences that were, you know came out in critiques of Obama as well. The right was just as vocal and sometimes just as conspiratorial when it came to the Clinton administration in the 1990s right? I mean that number of wild conspiracy theories that swirled around the Clintons were every bit as egregious and unwarranted and oftentimes strange as the conspiracy theories that whirled around Obama. So some of it definitely had to do with Obama’s racial identity but there’s more at work. And in part I think we also have to not simply write off every criticism of Obama’s policy as based in racial critique. There were legitimate differences about the size and scope of government activity, about taxation, about regulation, ah, about ah social welfare, ah, and about economic stimulus that can’t be boiled down to to racial animosity towards Obama that really speak to very deep divisions about the role of government and the economy and the society that have divided Republicans and Democrats left and right for you know going on 50 years now.

13:05 Blackmon: And one could imagine that it’s conceivably, best case scenario thinking, umm, that if a Donald Trump, let’s just say it this way. A Donald Trump might be exactly the kind of figure if he chose to be who could help find a new sort of dialogue around some of these issues. A new way of talking about some of these issues that have vexed the country for so long. We’ve made this tremendous progress in terms of race in so so many ways, but we still are obviously incredibly vulnerable around these issues. And as a part of this based dissatisfaction of so many of the voters who supported Donald Trump I think among poor whites and the people that I know well, I come from out of the rural South, is a sense that people look down on them, the economy has left them behind, ah, that Liberals and people in the cities are so quick to condemn them. And if it were to turn out that Donald Trump was someone who could help demonstrate in some way of showing, well, the mainstream of American life actually values those folks, maybe there’s a chance of some evolution of national language about how we talk about these things that could take some of the accelerant away from those conversations. I don’t know, is that pie in the sky hope?

Sugrue: I think it’s a pretty optimistic assumption given that one of the main appeals for Trump on the campaign trail was offering a kind of a narrow definition of what it means to be an American, right? Umm, Obama’s political rhetoric and political rhetoric of George W. Bush when he ran as a compassionate conservative for office in 2000, a bipartisan rhetoric at least was America is a diverse country with people from different backgrounds, a nation of immigrants, a nation that pulls together people of different backgrounds, a cohesive whole that treasures its many voices and different perspectives. And we didn’t get a lot of that on the campaign trail from candidate Trump. Ah, and so I think it’s going to be hard in part because nonwhite segments in the electorate for a very good reason are deeply specious of someone who criticized them. But the question about working class whites, working class whites those who have been suffering economic dislocation and have been mostly ignored, that’s a really big issue and maybe one of the most interesting issues to come out of the 2016 campaign. Not just from Trump but also during the democratic primaries from Bernie Sanders and even from Hillary Clinton who refashioned some of the Democratic platform and her own rhetoric to focus on those questions of dislocation. The real big problem in that the United States has faced is that neither party has addressed adequately but for the last 40 or 50 years is rising economic inequality, and the real insecurity, the gnawing insecurity of folks in the lower end of the economic ladder. This year it was white men who’s poorly paying insecure jobs and I mean they work two jobs to take care of their families.

FACTOID: 1971-2015: share of low income households grew from 25%-29%

Not being able to make ends meet, not being able to afford their mortgages, that moved to the center of the political stage. But for Latinos and for African Americans they were in many respects the canary in the coal mine. They have been dealing with these questions of economic inequality and displacement for decades now. And so I think for an adequate answer to this question of inequality and economic trouble is to think about ways of pulling together a policy that will address working class people, regardless of their background. Whether they come from small towns in the South or old industrial cities in the Midwest like where I grew up. Ah, whether they’re Latinos, or whites, or African Americans. And thus far I don’t think either party has particularly, adequately responded to those serious economic dislocations. We have a ways to go there.

17:19 Blackmon: So, this is looking far ahead, but the, if we go to 40 years from now and try to imagine what Democrats should be building towards or are likely to be building toward. More specifically what do you imagine Democrats are going to be trying to do over the next four years to prepare for what will be their effort to get everything back on a different, on a different road?

Sugrue: I think, ah, as with any transitional moment in party politics, there’s going to be a lot of soul searching. There’s going to be intense debate. There’s going to be struggles over who is going to set the new agenda. Umm, the Clinton wing of the party isn’t going to go away any time soon. That is folks who came up in the 1990s who are part of that reimagination of the Democratic Party making it more conservative on economic issues more liberal on social issues. But you also have the supporters of Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders who are calling for more powerful regulatory states. Calling for economic redistribution and you’ve got a very large and increasingly multi-cultural and diverse Democratic Party representing folks who are just coming into the electorate in significant numbers. I mean Latinos in particular. They’ve already changed the composition of the electorate in states like Nevada and Colorado but also in states like Arizona and Texas.

FACTOID: According to exit polls, Hillary Clinton won 65% of Hispanic vote

And as that generation of voters gets more numerous they’re going to push for a reorientation of Democratic Party politics in their direction as well. So I think we’re in for a really interesting ride with an unpredictable destination for the Democratic Party in the next two, four, six years.

10:15 Blackmon: Hmm, fascinating. You’re giving a speech this afternoon at the Miller Center, ah, what are you going to talk about?

Sugrue: I’m going to look at the ways in which Obama and the Obama administration was and wasn’t a transformative moment in American politics. Let me put it differently. I’m asking the question was Barack Obama a transformational president? And I am going to explore the ways that Obama was shaped and constrained by the policies of his predecessors and has more in common with Bill Clinton than many of his supporters hoped but also more in common with George W. Bush than many political pundits and observers would like to believe—both Obama supporters and Obama critics.

20:05 Blackmon: And do you mean on that are you talking primarily about his continuation of so many of the national security and foreign policy initiatives and like using even more drones and those things which he to some degree campaigned against and certainly campaigned on dissatisfaction about? But are there other dimensions that you see him as an extension of the Bush years?

Sugrue: Yeah, in foreign policy Obama carried on and expanded the antiterrorism policy of Clinton and Bush. There’s a great deal of continuity there. Much more than anyone would have expected. Guantanamo remain open. Ah, and that was one of the central pledges he made on the campaign trail to close it and close it quickly.

20:52 Blackmon: And he signed a memo about in on day one, right of his administration? Really amazing.

Sugrue: Right, but also on some domestic policy issues there’s more bipartisan agreement than one might expect even in this moment of polarization. For example, public education. Both the bush administration and the Obama administration put an emphasis on innovation, on competition, on bring market values into education. Both George W. Bush and Barack Obama were strong supporters of charger schools. And the differences between the parties around that issue were not nearly as great as one would have expected. Obama was the first urban president in decades, maybe in a century. Umm, and pledged early on in his administration one of his first executive orders was creating a White House office of urban affairs. But on urban policy, most of what he offered was a continuation of enterprise zone and and then renamed empowerment zone policies that came from the Bush and Clinton administrations. He didn’t depart significantly from the politics of his predecessors. There are ways in which we look at a president even when it promises to be transformational we have to understand that ah that that administration is shaped by and directed by the legacies and the policies that are already in place under his predecessors. It’s really hard to turn the ship of state.

22:22 Blackmon: So let’s imagine that it’s a few days after the inauguration sometime in early February and your phone rings and you pick it up and someone says President Trump would like you to come to the White House and spend ten minutes giving your best advice, ah, for in particular as an observer of all the things that you talked about, in particular he wants to hear from you and others like you about the best way for him to actually ah, get his hands around the rift in the country and push some semblance of the majority of Americans back together. But if you went to the White House given that opportunity, what’s the advice you’d give President Trump on how he can heal the nation?

Sugrue: I would say you have to roll back some of your harshest rhetoric around immigrants, around religious minorities, ah, ah, and you have to do that now. You should have done it yesterday. I would say secondly the parts of the government that are responsible for dealing with those kinds of issues, particularly the Justice, needs to be in the hands of folks who are still deeply committed to ferreting out discrimination—dealing with inequalities that persist by race and by ethnicity in American society. Those aren’t going to go away with the wave of a wand and they’re not going to go away even with the most lofty rhetoric. It requires people in place in institutions like the Department of Justice to address those problems. I would say perhaps most fundamentally umm, it’s important to come up with policies that deal with inequalities by class, by economic insecurity that affect all Americans regardless of their region, regardless of their race, regardless of their ethnicity. One of the most significant issues that any president would have to deal with is the persistence of insecure employment of relatively low wages, of working conditions that have been degrading for many Americans. Improvements in those arenas will benefit everyone. Umm, and I would say, umm, Mr. Trump, I’m skeptical that you will do any of these things but listen, ah, adapt and perhaps we’ll see movement in a positive direction.

Blackmon: Well let’s hope that ah, let’s hope that President Trump does some version of those things. Let’s hope that the best case scenario is the one that we get. Well thank you for being here. Tom Sugrue.

Sugrue: Great. Thank you.

Blackmon: If you’d like to send us a comment about this episode or join in our ongoing conversation about the big issues in American life, go to the Miller Center Facebook page, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @douglasblackmon. Our guest is @tomsugrue. For a transcript of this dialogue, or to watch other episodes, visit us at: millercenter.org/americanforum. I’m Doug Blackmon. See you again next week.