About this episode

April 30, 2017

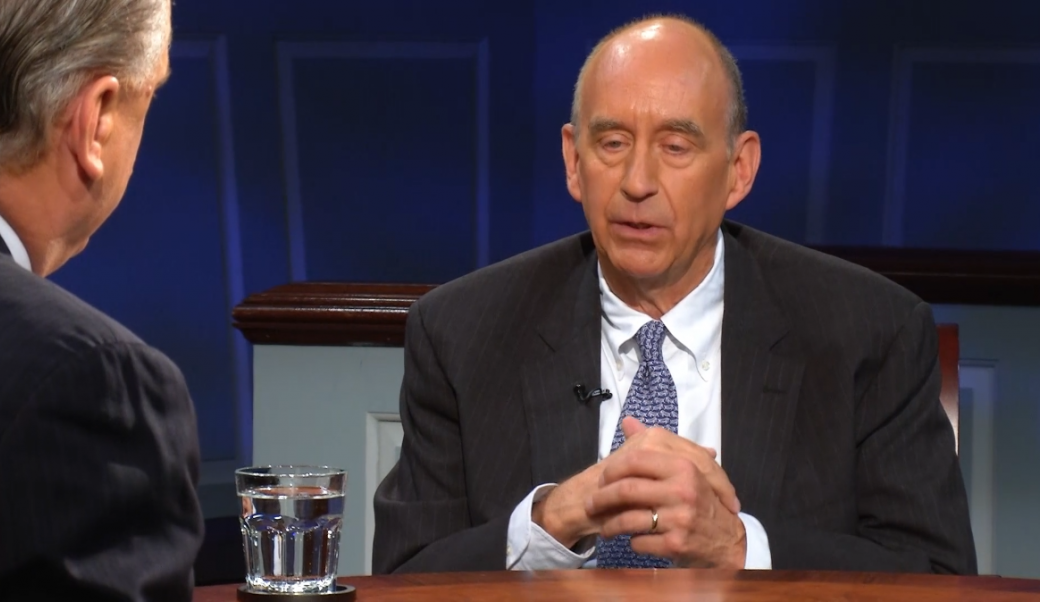

Peter Baker

New York Times White House correspondent Peter Baker assesses President Trump at 100 days. He and host Doug Blackmon cover a wide range of topics, including the handling of Syria and North Korea, Trump's learning curve, and the future role of media.

Transcript

04:41 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. It has become something of a tradition in our country to stop at the first 100 days of a new presidency and use that length of time to gauge the success or failures of an administration, compare that record to past presidents, and to look for signs of what the future may hold. The roots of the 100 days obsession go back to July 24th, 1933, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt used it on the radio during a Fireside Chat. Conveniently, his first 100 days had already gone by, and the administration had pushed an historic 15 major legislative initiatives through the 73rd Congress, launching his New Deal to save America from the Depression and, over the next generation, dramatically transforming the social structure of America. It may be unfair to judge anyone by the standard set by FDR, but the 100-day report card has been our tradition ever since. So in this episode, we’ve invited a journalist who couldn’t be more centrally located in today’s political world. Peter Baker is the chief White House correspondent for the New York Times where he has been a reporter since 2008. Before that, he worked twenty years at the Washington Post and has covered the administrations of Barack Obama, George W. Bush, and Bill Clinton. He recently suffered assignment whiplash when, after being relocated by the Times to become the newspapers Jerusalem bureau chief, Peter was promptly yanked back to the U.S. to resume the White House beat under another new president, Donald Trump. Peter Baker also spent four years as Moscow bureau chief, covering Vladimir Putin, resulting in the book Kremlin Rising: Putin’s Russia and the End of Revolution, which he co-wrote with his journalist wife Susan Glasser. After 9/11, Baker was among the first American newspaper reporters writing from rebel-held northern Afghanistan. This summer, he will publish a new book, Obama: The Call of History. He and his wife are also currently writing a biography of former Secretary of State James Baker. Welcome to the program.

Peter Baker: Thanks for having me.

Blackmon: You’re busy, man.

Baker: It’s a busy time. (laughs)

2:38 Blackmon: How do you do all that? How do you have one book coming out now, another one that’s in the works, and you’re covering the most, uh—the most news-intense presidency maybe ever?

Baker: Well, it turns out, sleep is an optional thing, and, uh, we try to get as much as we can. Look, we don’t get as much done as we need to, uh, but I always like having a project on the side, something to kind of think about after you deal with the day’s news.

Blackmon: Do you now actively as you’re reporting—do you have a file over here where you’re, like, parking notes that are kind of the book file or the book plan? I mean, are you that organized and on top of it from the beginning?

Baker: (laughs) I wouldn’t say I’m that organized, but it’s amazing how the book project will actually sort of inform the current-day reporting as well. So as we spend time thinking about James Baker, who was not just Secretary of State but had run Reagan’s White House in the first term, had run five presidential campaigns, he really had his hand in almost every major thing that happened in Washington for a generation. As we think about that period of time in Washington and compare it to today, it’s useful context, so I think that the two actually have more of a relationship then we might think about.

FACTOID: James Baker wrote 1995 memoir: The Politics of Diplomacy

3:39 Blackmon: There has been a tremendous amount of news out of the Trump administration, obviously, and anything could happen between the time that we have this conversation and when this program actually broadcasts on television, but let’s talk for a few minutes about the current hotspots. President Trump authorized this missile strike in Syria in response to a chemical weapons attack allegedly perpetrated by the Syrian regime and al—and no responsible person really doubts that it was done by that regime. That response by President Trump has gotten across the board pretty high remarks from both conservatives and liberals, but the but what do you make of the high marks that President Trump is getting for this one sudden act of decisive response in Syria?

Baker: Well, I think it actually stems back to the previous administration and sort of the frustration that a lot of people felt, including people who worked for President Obama, about their inability to find a solution to the Syria problem. This one strike isn’t going to be the solution to the Syria problem, not even close, but it was interesting to see not just Republicans cheer on President Trump but actually a lot of former Obama aides say, “Hey, it’s about time.” I think you’re going to interview, in fact, Anne-Marie Slaughter, who was one of the top State Department people under President Obama. She tweeted right afterwards, “Finally, enough handwringing. We’ve actually taken action.” It’s—it’s a reflection, I think, of the frustration that many people in President Obama’s circle that he didn’t act in 2013 when there was a similar chemical weapons attack, a much worse chemical weapons attack, but President Obama had always said, “Look, this isn’t going to accomplish anything,” and the mood of the country wasn’t really for a military action anyway on both the part of the Democrats and the Republicans at that moment.

FACTOID: Congress refused to authorize 2013 Syria strike sought by Obama

We forget that now. He also created a deal at the time with the Russians to remove all of Syria’s chemical weapons, but we now know, obviously, that that deal didn’t completely work.

FACTOID: Russia is staunch Syrian ally and supplies weapons to its army

But, you know, I think it’s also a sign of a sense on President Trump that, OK, actually he is within the four squares of traditional foreign policy. We may or may not agree with the strike, but this is something that other presidents have done and it is—uh, was proportional. It wasn’t over the top. He didn’t start sending in lots of troops, and I think that there was a sense that, OK, we understand this kind of foreign policy at least, whether we agree with it or not.

6:00 Blackmon: But is that part of it, just that, OK, finally the guy does something that is normal for a president and feels decisive

Baker: And it didn’t feel like it had been messed up in some way? Yeah, I think that’s exactly right, and he has a good team around him of people like Jim Mattis, the Secretary of Defense, and H.R. McMaster, the National Security Advisor, who were reassuring to many of the establishment people in Washington, both Republicans and Democrats, and he didn’t—and he didn’t take it beyond that. What’s interesting is, when we watch President Trump’s Twitter feed, he’s willing to say or—or troll basically anybody, you know, anybody at least within the borders of the United States.

FACTOID: Trump has over 28 million Twitter followers; has sent 35K Tweets

If he feels offended by them, he’s going to say whatever he feels like on Twitter. He didn’t do that with Bashar al-Assad. He didn’t try to escalate this beyond this one episode.

FACTOID: Trump has added over 15 million Twitter followers since election

Now, that may mean that this is therefore a one-off and goes away and doesn’t really change events on the ground. That’s going to be a really interesting questions, because he doesn’t seem any more inclined than he was during the campaign to suddenly involve us in that civil war more deeply, a quagmire that President Obama spent a lot of time trying to avoid.

7:03 Blackmon: We did have candidate Trump who along the way said that—that the American military was in terrible shape. He loved the soldiers, but the military was in terrible shape, that he knew more about these issues than—than the generals do.

FACTOID: Trump wants $54 billion in new defense spending—increase of 10%. Now, we have a very different-looking kind of picture where he—you know, he believes the intelligence reports that say Assad, uh, ordered this gas attack. What’s happening here? You know, is the—is—is it that the president now has turned over, uh, some of these areas of responsibility to other people and now has confidence in them and has confidence in some intelligence stream, or is it still just kind of making it up every day as he goes along?

Baker: Yeah, that’s a great question. Look, there’s an education process for any new president, and that’s what we see in every first 100 days. It’s particularly pronounced for this one. Why is that? Because, of course, he’s the first president in American history never to have served in government or military. It’s all new to him, and even politicians who have served at lower levels it’s hard enough for, but they at least have some political instincts. They have some instincts about issues. They have some, uh, understanding of how things work. This is all new, so President Trump is—is—he’s getting some on-the-job training in that sense, and how he adjusts to that will be an interesting question. He is an unpredictable per—person, so I think that we have to be careful when we sit there and think, “Aha, this is a pivot from this type of president to that type of president.” Any given moment, it could change back or change in a whole different direction.

8:27 Blackmon: Which is what we saw all through the campaign where there would periodically be these, “Oh, the presidential version of Donald Trump has appeared,” and then—and then things would shift back another way.

Baker: Yeah. Donald Trump is still Donald Trump.

8:36 Blackmon: Yeah. So does this seeming moment of coherence or whatever it is that we’re seeing right now—does it relate to the—what we’ve heard about in terms of this, uh, tension between the president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and his chief strategist, Steve Bannon, though now the president says he’s his own strategist—but whatever this palace intrigue is, does all of this relate to that somehow? Is it the emergence of a different advisory voice that has a more cohesive idea of how this administration should work or—

FACTOID: Bannon, 63, was film producer and a founder of Breitbart news

Baker: Well, when you have a president who doesn't have political experience and doesn’t seem to have a very defined core ideology, you’re going to have, uh, a fight for the control of that presidency, and that’s what’s happening here. So it’s not just a matter of personnel or who’s up or who’s down, classic Washington scorekeeping. It’s a matter of what does this presidency stand for, and people are trying to puzzle that out. Is he the, you know, sharp conservative populist, the firebrand that we saw at various moments on the campaign trail, “We’re going to ban all Muslims from coming into the country. We’re going to, uh, throw out 11 million illegal immigrants. We’re going to, you know, get rid of Obamacare on day one. We’re going to move the embassy in Israel to Jerusalem,” or is he the more pragmatic New York businessman who, frankly, likes to cut a deal and, you know was a Democrat in the past?

FACTOID: Trump changed party affiliation seven times; most recently in 2012

And—and, uh, I think we see on different days different Donald Trumps, and so when you see a Steve Bannon and a Jared Kushner and a Reince Priebus fighting with each other, they’re really fighting for Donald Trump, and they’re trying to influence the president and push him in a different direction.

FACTOID: Priebus, 45, is lawyer and former RNC chair and general counsel

For Steve Bannon, it’s important to stay true to the ideals, as he saw them, of the campaign, which means to stick close to the conservative populism, the nationalist kind of, uh, approach that he had championed, because, after all, he says, “You’re not going to win over those Democrats anyway. Don’t try to cater to them. Stick to the people who brought you here, and they’re going to deliver a second term to you.” And then, you’ve got the Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump part of the White House which is saying, “Oh, we hate this avalanche of terrible press you’re getting. You’re, you know—don’t—why are you just creating all this friction with people unnecessarily? Let’s try to shave off the harsh edges and see if we can’t find some deals.”

10:48 Blackmon: Who’s winning?

Baker: Well, I think history shows that any palace where there’s a fight between family and not family, you’re better off putting money on the family. Family tends to win in most circumstances. Now, we don’t know. We’ll see, but it’s a lot harder to fire your son-in-law than it is to fire your chief strategist.

FACTOID: Kushner married Trump daughter Ivanka in 2009; have three children

11:06 Blackmon: The situation in Syria is so much more complicated than the basic narrative of the last few weeks, and—and so let’s remind ourselves that if we go back to 2013 there was this chemical attack that was much more serious, far more people killed than the most recent one, and so, arguably, would have been—been worthy of an even more substantial response. And this was after President Obama had—had made reference to his red line. It certainly is still an incredibly messy situation, but is it as clean as that—the Obama administration just missed the ball, and now the Trump administration is getting it right? It can’t be that simple.

Baker: No, of course it’s not that simple, and I—I think that what President Obama was very clear on is, you know, there’s no point in intervention that’s not going to succeed that simply gets us into another Iraq-type war. And in that sense, he had, you know, his finger on the pulse of the American people. The American people didn’t want another Iraq war either, and President Obama was constantly frustrated by the critique of his Syria policy and basically saying, “Well, fine, what would you do?” And the answers were never satisfying to him. He called them half-baked. He called them, you know, uh—things that wouldn’t be successful, whether to create a no-fly zone or a safe zone, whether to, you know, arm Syrian rebels earlier and more robustly. But, you know, he was a party of one within his own White House on that. There was genuinely a—an appetite, a desire by the people working for President Obama to do more. And while none of their solutions were clearly magic-wand fixes, they felt that there was a moral obligation to get more involved, not to necessarily have a big Iraq-type presence but to be at least more, uh, aggressive. Now, President Trump has not decided that means he’s going to suddenly take on the Syrian civil war as his priority. He said during the campaign, “Syria is not America’s problem.” That was his quote on Twitter. And just because he had this particular red line on the use of chemical weapons doesn’t mean it’s going to be anything further than that. Eighty people died in that horrific chemical weapons attack, but more than 400,000 people have died through plenty of other types of killing in Syria, and there doesn't seem to be a sign that that’s going to suddenly provoke an American, uh, response. So, you know, Rex Tillerson went to Moscow to see if there could be a deal with Russia. John Kerry tried that again and again and again, beating his head against that brick wall, and I suspect that, uh, you know, at the moment, anyway, there’s no sign that there’s a—you know, a resolution on the—on the horizon.

13:37 Blackmon: Well, it’s also extraordinary that the—that the actions taken by the Obama administration that now are the subject of such criticism and must have been a total failure were deeply involved making a deal with Russia in which Russia then negotiated the removal—

Baker: Absolutely. Right.

Blackmon: —of at least a large portion of the chemical weapons, and so—

Baker: And we should not forget, in 2013 when Obama chose not to strike Syria in response to that chemical weapons attack, he was urged on in that position by Donald Trump, then a private citizen, saying, “Don’t do it, Mr. President. It’s not in our interest.” So he has had a big change in that four-year period.

14:12 Blackmon: Well, I want to ask you a question that’s related to all of that, but it’s also really more a question about media. Uh, now, you’re a longtime legendary reporter. I worked for a long time at the Wall Street Journal. Uh, we both know that in the culture of people who work in this business, uh, that we quietly criticize each other’s work all the time, but generally one White House correspondent doesn’t very often go out and say, “I think my counterpart White House correspondent totally blew it yesterday,” in part because you don’t want that guy coming back and saying the same thing about you the next day. (laughter) But the—but so—

Baker: Honor among thieves.

Blackmon: Honor among thieves, exactly. But I’m going to identify a particular interview that happened recently related to all of this, and it’s not to beat up on this one journalist, Maria Bartiromo, formerly of CNBC, now Fox. But Maria, who is a serious journalist—and I say that to distinguish her from figures like Sean Hannity or Bill O’Reilly, who are not serious journalists, and I think we can fairly say that, not really journalists at all. But Bartiromo is somebody who has a reputation, mostly in business coverage, but is somebody who wants to be a serious journalist. She does an interview with President Trump in which there is discussion of the strike in Syria, and President Trump squarely blames the chemical attack itself—as have others in the administration—on President Obama, that the failure of President Obama to have done something in the past is why all of these children and innocents died in Syria, which is a very serious thing to say about—about a former president. And—but in the course of this interview, the president says those things, but then Bartiromo, the journalist there, doesn’t—just nods her head, doesn’t say, “But wait a minute, on September 5th, 2013, Mr. Trump, President Trump, you tweeted out, ‘To our very foolish leader, Barack Obama, do not attack Syria. If you do, many very bad things will happen. The US gets nothing.’ Two days later, candidate Trump says, ‘President Obama, do not attack Syria. There’s no upside and tremendous downside.’” Have we arrived at a time—in the midst of all of this concern about fake news and what’s really a fact—is actually a time that it’s not just the media columnist at the New York Times or the Washington Post that should observe this—essentially malpractice, journalistic malpractice. Shouldn’t it be the case that the New York Times would report that another media organization yesterday broadcast an interview with the president, uh, that gave a profoundly misleading description of relevant facts? I mean, is that something that—that serious journalists should be—should break out of, of the restraint that has said, “Well, let’s just let the—let’s let the viewers and the readers decide for themselves whether they believe that”? Is it time to call that out?

Baker: Well, I think we do have a very, uh, talented team of media reporters who, in fact, do spend time thinking about what our obligations are as media and do, in fact, spend time talking about how other media organizations as well as our own approach these things. But we are collectively an institution in society that is important, and we need to cover ourselves and scrutinize ourselves with the same degree of skepticism and accountability that we apply to other institutions in American society.The New York Times, by the way, should be subject to that as well. We should be subject to criticism, and we do in fact have a public editor whose job it is internally and in a column once a week on Sundays to say, “Here’s where the New York Times screwed up.”

FACTOID: NYT started public editor job in 2003 after Jayson Blair fabrications

17:30 Blackmon: And to the Times’ credit, most of the folks who have played that role clearly, uh, have been more aggressive in their critique of the Times than is typically the case in any organization.

Baker: It’s healthy. It’s healthy. We have to scrutinize ourselves.

17:40 Blackmon: But so back on foreign policy, the, um—there is also a lot of discussion that the real issue in the world right now is not Bashar al-Assad and the atrocities that are happening there but North Korea. owHHow serious is that situation?

Baker: Well, it is serious. Obviously, North Korea is a very volatile and unpredictable, uh, regime that has nuclear weapons, and it’s—it has grown more so over the years.

FACTOID: President Bush called North Korea part of “Axis of Evil” in 2002 speech

Uh, you know—and we don’t know yet what President Trump’s approach is to it. President Obama’s approach basically was sort of like benign, ignoring the problem, keeping him isolated, keeping them, uh, boxed in without giving them more attention on the world stage. That has allowed him to—that has allowed Kim Jong-un to continue to build up a—an important and dangerous arsenal. It’s such a tinderbox, and—and I’ve heard people who are smarter than I am about this saying that, you know, we pay all of this attention to the Middle East, but the one thing that might get us into a truly awful situation in the next few years even—no matter who is president is North Korea. So it’s—we should be watching carefully to see how President Trump decides to approach it.

18:44 Blackmon: And is it your sense that the—that the people who are advising President Trump, uh, as it relates to North Korea are in the group of folks that—that people have more confidence in outside the administration? I mean, are—is this one of the topics that’s in the safe zone as opposed to, like, EPA and a lot of other issues? Is that your sense?

Baker: Well, I don’t know about a safe zone, but, I mean, certainly there are a lot of people working on it who are serious professionals with a lot of experience. His Asia advisor, Matt Pottinger, is well respected, obviously the defense secretary, Jim Mattis, and the—and General Dunford, the joint chiefs chairman. Keep in mind, the military guys in most of these situations are usually more reticent than civilians to want to use force because they know the consequences of it and they know that, often, it doesn’t accomplish what a civilian leader wants it to accomplish, so he’s hearing those voices presumably from, uh, the generals, as he calls them, uh, surrounding him. There’s an inevitability at some point to finding some resolution to this problem. He hopes the Chinese will be the solution. The Chinese have great influence, obviously, over North Korea, but they’ve been reluctant to do the things that American presidents have been asking them to do now for twenty years.

19:47 Blackmon: Uh, you were here about eighteen months ago, and you—you said something that turned out to be quite prescient.

Baker: Uh-oh. Uh-oh. (laughs)

Blackmon: Usually, when I remind people of what they said here before in this category—

Baker: That doesn’t work out well.

20:00 Blackmon: It’s someone saying that, uh, there’s no chance Donald Trump could ever become president, but you’re not in that category. You didn’t say that.

INSERT PREVIOUS PETER BAKER :19 SECOND CLIP HERE

Baker: “the thing that she probably has to worry about the most is probably not Republicans in the Congress but the FBI. If somebody gets in trouble because of this email thing, if there happens to be some sort of criminal liability somewhere along the way something somebody did something they shouldn’t have with some of these emails, then that’s a much more serious issue that could change the dynamics overnight.”

20:25 Blackmon: Did Donald Trump win the election, or did Hillary Clinton lose the election?

Baker: Well, that’s a great question. I mean, certainly Hillary Clinton did not—you know, did not win something that was in theory a very winnable election for her. She had all of the, uh, normal advantages of a—of a frontrunner: money, status, experience, a party that at least, if it was not necessarily unified, at least certainly was unified in its distaste for the other guy. And yeah, she was very, in the end, not a successful candidate for a variety of reasons. One is that she wasn’t—it’s not a natural thing for her as it is for her husband to be out there on the campaign trail, and she didn’t project, uh—

21:08 Blackmon: But does it also just boil down to fundamentally a sense of—of mistrust?

Baker: It does. Yes, I think people did not trust Hillary Clinton, and a lot of people who voted for Donald Trump didn’t vote for him but against her.

FACTOID: September 2016 poll: 33% “trusted” Hillary Clinton, Trump 42%

They just couldn’t accept her. Uh, now, some people on her side would say that’s, you know, gender-related, sexism on their part. Some people would just say, “Look, it’s a matter—it is a trust thing,” that the email thing corroded that. And some people, by the way, would blame the media for—you know, on the left, they would blame the media for overemphasizing that when we knew that the Russians were meddling around in there. So the Clintons have been on the stage for a long time, and there was clearly a certain exhaustion, I think, with that. And there was a desire on the part of at least a certain part of the American public to move on, do something different, to shake things up. Mind you, it’s still a minority. You know, she won more votes than he did by three million, but that’s not the way the system works, and I think there’s plenty of reasons to look at for why it didn’t work.

22:03 Blackmon: Whatever side of the political equation anyone is these days, they have a sense that—that we’re a country in crisis in some fashion, that our political process is deeply troubled, that there are all kinds of things going wrong. You must be—if you’re not the smartest, most informed man in American you’re certainly in a very small group of people that—that would fit that definition. Uh, and it’s not your job as a journalist to do this, but I’m going to ask anyway: give us a solution to anything. Pick something, and give us a solution. What is something that would—what is something that a citizen could do? What is something that President Trump could do? What is something that journalists could do? But give us a solution to something.

Baker: (laughs) Wow. Look, I'm a big fan of America, and I’m a big fan of American institutions. And I think that the truth is there’s a lot of sort of handwringing out there right now because things do feel like they’re discombobulated and is, really, America, you know, in a screwed-up place right now. And I just have great faith that we’re going to get through this moment through the things that we have built over 200 years, 250 years. And, you know, we’ve been through rough times before. We went through the ’60s and the and the tumult over race and gender and the Vietnam War and Watergate, uh, and—and we came out of that. And we are in a tough moment right now. We were in a tough moment after 9/11 and after the financial crash. I’m a big believer that better days are ahead, and I think that that’s because of the things that America has built over time in terms of a private sector, in terms of a government, in terms of a balance of power between the courts and the Congress and the president, and because of the media. So what’s one thing we can do? One thing we can do is, in fact, strengthen our media and commit to truthful reporting as best we can determine it and find ways of, uh, minimizing or marginalizing or dispensing with, you know, what we call fake news, not what necessarily the president calls “fake news” out there, and—and have a commitment to true facts. And then, we can have a healthy debate about what these true facts should tell us about approach and policy and so forth, so I think that right now our focus, my focus, and the focus of my colleagues is building up and, uh—and demonstrating the value of an independent media as best we can. So I hope that’s part of the solution.

24:30 Blackmon: That’s great. Thank you, Peter Baker.

Baker: (laughs) Thank you.

Blackmon: Before we go, a quick shout out to the organizers of the Tom Tom Festival in Charlottesville, Virginia. It’s one of the great new gatherings around big ideas that is happening in America these days about solutions. Last night, all of us at American Forum spent the evening there talking about President Trump’s first 100 days with our guest Peter Baker and also with US Senator Mark Warner, Miller Center scholars Russell Riley and Nicole Hemmer, and our colleagues on the NPR radio series BackStory with the History Guys. Hundreds, and I think it might have even been thousands, of engaged citizens joined in. It’s fair to say there’s no lack of interest in political discourse and looking for solutions right now. We hope you’ll join us for future editions of American Forum where our focus is always on the presidency and the issues the president faces. Upcoming guests include Northwestern history professor Geraldo Cadava on the future of Hispanics in this country and Rich Lowry, editor of The National Review. You can watch us on your local PBS affiliate or, to join our ongoing conversations, look for our broadcasts on the Miller Center Facebook page. Visit our new, revamped website at MillerCenter.org, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @douglasblackmon. Peter Baker is @peterbakernyt. See you next week.