From the director: Assessing a first year like no other

The Miller Center's director and CEO lays out the case for the '5 Ps' in a presidential first year

[Read the full article in US News]

How to assess Donald Trump’s First Year?

The president claims credit for a booming stock market, low unemployment, bureaucracy-killing executive orders, and (soon) a major tax overhaul.

Critics see assaults on the rule of law, free press, democratic norms and institutions, the environment, our electoral system, and our global standing.

Amidst the hyperbole, it is possible to track Trump’s first year across five Ps of presidential power.

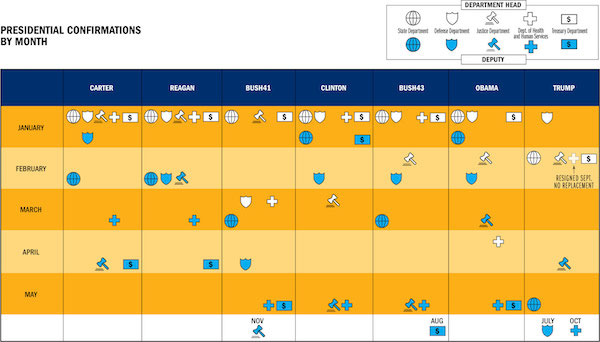

Trump lags his predecessors in filling key posts. Eleven months in, he has confirmed only 260 appointees—roughly 60% of Obama’s 418 and a little more than 50% of George W Bush’s 483.

The Department of Treasury still needs a deputy. The State Department lacks five of its six under-secretaries. These officials, who run the government on a daily basis, are particularly important— especially when crisis hits and cabinet secretaries are scattered.

And then there’s turnover. The president has replaced his Chief of Staff, National Security Advisor, Press Secretary, Communications Director, and two cabinet secretaries. Trump’s fast revolving door is unprecedented.

Good process makes good policy. A new president needs a team working together to advance an agenda and to protect the nation. Nearly every White House stumbles at first.

Reflecting on a series of crises in 1989, in the first year of the first Bush presidency, Dick Cheney told the Miller Center, “There isn’t any process today by which the new team, when they get on board, get any of that experience.”

So far, the Trump White House has issued executive orders on immigration and national security matters without consulting key agencies. National security council meetings have been held in restaurants. There appears to be no process on vetting the president’s tweets—nor will there be.

Chief of Staff John Kelly, National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster, and Congressional Affairs Director Marc Short have each worked to fix their processes. All administrations stumble. The question is how they respond.

Even with a short staff and chaotic management style, Trump has advanced his campaign priorities.

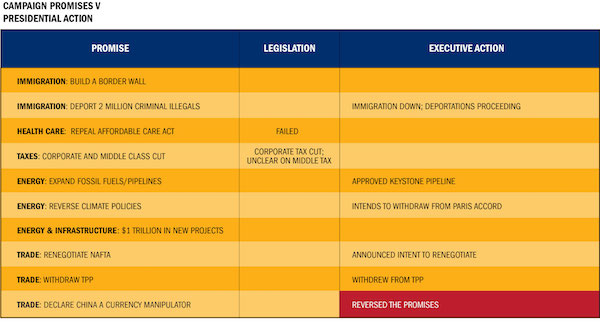

As a candidate, he promised a 100-day agenda focused on immigration, health-care, taxes, infrastructure, trade, energy, and the environment. He also promised to confirm a conservative Supreme Court justice.

On April 7, the Senate confirmed Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch.

Congress also passed the Congressional Review Act, which streamlined Trump’s ability to rescind Obama-era regulations. Eleven months later, Congress passed a tax bill. It fulfilled one promise (cutting corporate taxes) but appears to have failed to fulfill another (cutting middle class taxes by 35%).

Between those two bookends, Congress failed to repeal and replace Obamacare. Nearly all of Trump’s other wins have come from executive action—a trend begun by Obama, to the consternation (at the time) of many conservatives. Homeland Security has stepped up deportations. EPA and Interior have promoted coal and oil-and-gas exploration, accelerated pipeline construction, and gutted the Clean Power Plan. Other agencies have looked to lift administrative burdens on companies.

On foreign policy, Trump has so far avoided a catastrophic first year crisis, such as the Bay of Pigs, Blackhawk Down, or the Al Qaeda attacks in 1993 and 2001. He also has lacked first-year breakthroughs, such as the Camp David Accords or the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Trump has followed through on campaign pledges to abandon the Paris climate agreement and the Trans Pacific Partnership, start renegotiations on NAFTA, and move the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem. He also has continued Obama’s surge against ISIS, leading to a near rout in Iraq and Syria.

Other goals remain unresolved or abandoned, including forging a new relationship with Russia, declaring China a currency manipulator, or winning nuclear standoffs with Iran and North Korea. Allies in Europe and Asia are concerned, at best; frustrated and looking elsewhere for leadership, at worst.

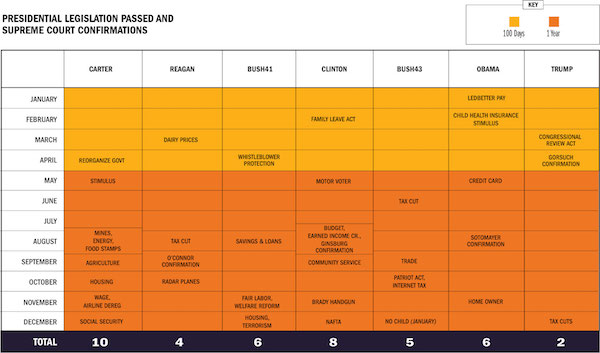

Lyndon Johnson once said that a president has one year to work with Congress, after which members care only about their reelection. Johnson warned that a president can struggle, even if his own party controls congress. Bill Clinton and George Bush each managed to pass two major bills in their respective first years. Barack Obama passed the Recovery Act, protections for children, workers, and homeowners, and eventually, the Affordable Care Act in month 13.

Compared to other presidential first years when one party controlled the Executive and Congress, the “win” column is quite small. Indeed, despite his 100-day promise, Trump seems to view Congress as an unreliable partner, treating legislation as the second option, not the first.

A GOP-led Congress has, in a few instances, acted to constrain Trump. Congress passed increased sanctions against Russia with veto-proof majorities. Investigations into the president continue, challenging Trump’s commitment to the rule of law.

Trump’s performance has contributed to Democratic wins in the gubernatorial races in Virginia and New Jersey and in a Senate special-election in Alabama. Republicans looking ahead to midterm elections are now fearful. Despite an enthusiastic GOP base, surveys suggest that moderates are leaving the party.

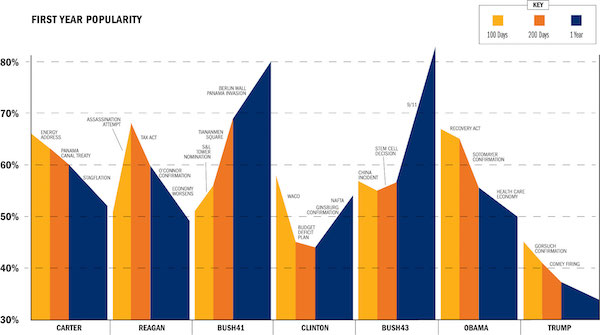

Trump became the first president in the last four decades to be inaugurated without a majority of public approval. And that has been his high water-mark.

He remains the least popular president since the inception of presidential polling, and only Gerald Ford’s presidency comes close. The party Trump leads is in the worst polling position a year out from a midterm since at least 1938.

Previous presidents have reversed first-year slumps through bipartisanship. Clinton dipped below the 50% threshold. He was able to turn his numbers around after passing NAFTA in November 1993. George W. Bush slumped too, but rebounded after the September 11 attacks and the bipartisan No Child Left Behind law.

Trump has yet to claim a bipartisan domestic or foreign policy win strong enough to boost his standing.

Then again, he may not care. At a time when both political parties are fractured, the president seems to be betting on political division. If either party splits, and the 2020 election features a centrist third-party candidate, the president’s 40% poll number may be enough to keep us all up late on election night.