About this episode

May 27, 2016

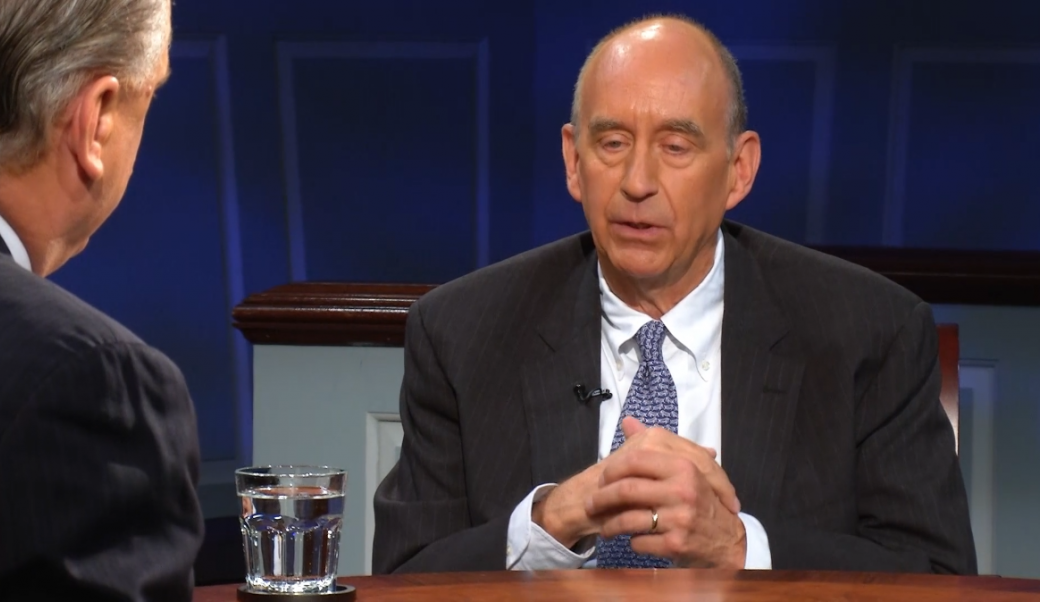

Gary Gallagher

Gary Gallagher is the John L. Nau III Professor in the History of the American Civil War and director of the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History at the University of Virginia. In this episode he discusses the first year of Abraham Lincoln's tenure, undoubtedly the most challenging first year in American presidential history. This episode is part of the Miller Center's First Year Project.

The Presidency

The worst first year of a presidency

Transcript

0:41 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. We are deep into one of the most surreal presidential campaigns in recent American history. Maybe in all of American history. The country is deeply divided. The Republican Party is in a kind of internal civil war. And there are substantial challenges occurring to the unwritten courtesies and other basic understandings between our government leaders that have been crucial to making American democracy work for nearly 250 years—how Supreme Court justices are appointed, how budgets are passed and money borrowed, who should negotiate with foreign powers, how opposing parties interact constructively. As the November 2016 national election grows closer, it seems like a good time to begin discussing these divisions and some of the other critical issues that will face our next president most urgently during her, or his, first year in office—regardless of who that president may be. We'll turn back to this many times over the next year, exploring a range of urgent questions. One of the most obvious will be how the new president handles the pervasive bitterness of the current political environment. So in this episode we turn to Professor Gary Gallagher, a celebrated historian of the most divided time in American history—and an expert on the worst presidential first year of them all—Abraham Lincoln’s. Gary, Thanks for being here.

FACTOID: The Question: What was the worst first year for a president?

Gary Gallagher: I’m very happy to be here.

Blackmon: So maybe it doesn’t make sense to be talking about Abraham Lincoln and events of 150 years ago in the midst of a presidential campaign in 2016, but so what was it that made that such a terrible first year other than the fact that the country was on a course towards civil war and had arrived at civil war?

Gallagher: Well the other than part of that is the key of course other than the fact that there was already another nation in being. He gave his first inaugural in March of 1861 and there was a seven state sister republic in place with a capital in Montgomery, Alabama.

FACTOID: In 1860, seven states seceded to form Confederate States of America

FACTOID: Lincoln was president from 1861 until assassination in 1865

So that is, that alone sets Lincoln completely apart from any other president who’s faced a first term. I’m amused, in fact I would say vastly amused, when I hear that conditions have never been as contentious as they are now and we’ve never been as angry with one another. Of course that’s not true. And the proof of that is to take a look at the state of the United States in late 1860 and early 1861. Lincoln is facing the question of how to try to bring the nation back together. That’s his view of the crisis. The view from south of the Potomac River is that’s not a question any more. We’re another nation and that’s the way it’s going to be. But his view is how do I get this back together? How do I try to remedy a situation that’s reached this point?

3:22 Blackmon: In terms of the bitterness and the division we see in the country today which obviously is so different in the sense that we do not appear to be on the verge of violence among the various parties or the differing interests in American life right now, but it does feel incredibly bitter and divided. But so is it crazy to even talk about Lincoln and that period of time in this context? Or is there some connection?

Gallagher: No I don’t think it’s crazy to do that because Lincoln is trying to, he comes into his office with his eye on the ball as he would say, and that is to bring the Union back together. That’s his goal. His whole first year in office is, is preeminently about that. What can I do to bring the Union back together? And he’s forced to reach out to very different constituencies including those who’s already left the United States. So it’s, he knows there are these tremendous divisions. He’s trying to reach across some of these chasms and get enough support from different quarters to achieve his goal of union. And I think now whoever is going to come into office now is going to have to be aware of how divided we are now. And I think Lincoln’s example is you don’t ignore all the people who don’t agree with you. You realize it’s going to take a cooperative effort to make something good happen. And so you have to craft your policies, your message to reach out in other directions.

FACTOID: Lincoln entered politics as Whig, became first Republican president

4:41 Blackmon: I think the conventional wisdom is that in the present situation that President Obama for the past eight years has this idea that in particular he has faced this very obdurate and unwilling to cooperate even if he wanted to cooperate a Republican controlled Congress during most of the eight years. That’s the most conventional telling of things. It’s also the case that from the perspective of the GOP that President Obama early on said this is what elections are about, I’ve got a, I have a mandate. And he was perceived by some . . .

Gallagher: I think he even said go to the back of bus.

5:18 Blackmon: At some point, yea. And so this idea that in reality we’ve had both sides and went on the debate but both sides certainly have approached this with at times with what looked like an iconoclastic attitude. And, so Lincoln back in 1861, what are the, what are the iconoclasts that he’s facing even among those who are still within the nation?

Gallagher: Well I think there’s one real similarity between then and now and that is that across these divisions people expected the worst and projected the worst on the other side. And when the other side would say something they just didn’t believe it and said you’re lying. For example, Lincoln came in and said it was a Republican platform in 1850 and Lincoln said he had no intention of interfering with slavery where it existed. And the slaveholding states said well, you’re a liar. You gave a speech in 1858 that said a house divided cannot stand. It’s going to be one thing or the other and we know which way you want it to be. So you’re a liar and we’re not going to listen to anything that you say. I think there was a great deal of that unwillingness to take even a small step toward the other side that created this very toxic situation. I think we have some of that now where people don’t really, they’re not really interested in debating they just sort of yell talking points at one another and then leave. The great issues in Lincoln’s time were all related to slavery and especially to the extension of the institution of slavery into the territories. And there was an unwillingness to believe what someone was saying because you think you know what they really mean or what they really want and they’re just lying to you.

FACTOID: See millecenter.org/president as resource on U.S. presidency

And Lincoln confronted a great deal of that as he came into office. He also had a profound division within his own part of the country the part that remained loyal between Democrats and the Republican Party. There’s another similarity between then and now and we see two great parties, two old great parties really in a situation with profound unhappiness among people in different parts of them. The same thing happened in 1860 when the Democratic Party which had always been a majority party, Jefferson’s party down to then. It literally couldn’t cope with the question of how to finesse slavery in the territories. And it disintegrated as a national party. Some people might talk about how that might be in progress now, who knows? But the phenomenon is certainly similar.

7:45 Blackmon: You also had at that time in the lead up to the Civil War and during the Civil War, a kind of perplexing division in the interest between, even around slavery. The number of families that own a significant number of enslaved people is relatively small.

Gallagher: Very small.

8:00

Blackmon: And the economic interests of being of slavery expanding into other territories presumably would have benefitted those who were already in the business of slavery and enslavement somehow. And then you have this other huge population of southerners who don’t own slaves and arguable are disadvantaged in some respects by the or not?

Gallagher: Well we say that. And they might be disadvantaged in some ways economically, although not always. There are lots of reciprocal relationships between slaveholders and nonslaveholders, white nonslaveholders. But they all had a stake in white supremacy. They all had a stake in controlling black people. Virtually all the black people lived in the slaveholding states. The slave states were 98.8 percent white in 1860.

FACTOID: 185,000 blacks, more than 85% of those eligible, fought in the Civil War

So you have millions of white people living among millions of black people they know don’t want to be slaves, whatever they said later. And the question is how do you control them? So whether you’re a slave holder or not a slave holder you fear what might happen if black people really take it upon themselves to change the situation. here were people in 1860 on both sides who genuinely believed the nation had evolved into two separate cultures, really separate cultures. They would say separate civilizations. They really believed there were fundamental differences between them and all of those were rooted in some fashion in the fact that one was a slaveholding society and one was not. And, but they believed it. And what they believed is it doesn’t matter if it’s true or not. If they believed it, they behaved on the basis of that belief.

9:36 Blackmon: And it’s ironic though that as time goes by that the great disputed what did they really mean question about that whole period of time is whether the Civil War is really about slavery or not. (Gallagher: Right.) And you’ve written and said before that obviously the Civil War was overwhelmingly about slavery but then post war all the Confederate leaders say no it wasn’t and right up to the present we still have this very active debate in which many people say no it wasn’t about slavery at all.

Gallagher: The coming of the war was about slavery. Causation was about slavery. But in terms of motivation most white northerners would have said the most important thing was union. Not the most important thing was emancipation. But it, it, gets after the war former Confederates tried to distance themselves from slavery in that regard because they knew they were out of step with western civilization. And if they wanted a favorable hearing before the bar of history they couldn’t say what the truth was. Our republic came about only because we were trying to protect slavery. Not just the economic side of it but the social control part of it as well.

10:36 Blackmon: Yea, and this thing that we believed absolutely that the election of this man, Abraham Lincoln, spelled, would bring an attempt to bring an end to slavery.

Gallagher: Absolutely, absolutely believed that that’s what he wanted and of course he did want that. I mean they weren’t wrong on some levels. Lincoln did hate slavery but he, Lincoln reached out even to white southerners in states that had seceded. That’s something that doesn’t seem to be happening much now.

FACTOID: First states to secede from Union: AL, FL, GA, LA, MS, SC, TX

He reached out to them and said look, we share things. And he evoked revolutionary heritage, he evoked the meaning of the Union to everybody who benefitted from the work of the founding generation, the revolutionary generation who shed their blood. He closed his first inaugural with that very lyrical tribute to the Union. That was aimed at people all over the nation. He kind of crafted his message about the Union to meet different parts of the population. He reached out in every direction. There’s not a lot of that going on right now I don’t think. Or I don’t detect it.

11:38 Blackmon: So in many respects it is a case of ah a case of astonishing capacity to compromise in what looks like the most divided uncompromising moment of all. But actually it’s not.

Gallagher: He’s trying. He is on a very treacherous path for a politician. I mean how can I calibrate this so I don’t offend these certain key groups. That’s what he’s doing in this first year. And the way that he decides to do that is to absolutely, I’ve said this already but I’ll say it again, he absolutely focuses on Union. In his first inaugural. In his message to the Congress in July. In his first annual message to Congress in December. It’s always Union, Union, Union. With special sections aimed to the border states, other, I mean he’s he’s keeping the whole picture in mind and of course alienating some people as he goes along including radical Republicans in his own party and abolitionists who want him to go faster on emancipation.

12:31 Blackmon: Were there any other issues at the time? Did Abraham Lincoln have any other legislative agenda? Anything else?

Gallagher: There were. The Republican Party had an agenda of what we would call a sort of modernizing capitalist vision of what the United States would be and it included reforming the banking structure, creating a national bank. Ah, tariffs that would protect industry, the Homestead Act, the intercontinental railroad, all of those things. And they actually passed their entire legislative agenda, at least most of it in 1862 and early 1863. So that’s going on and ironically it’s the departure of all the southern Democrats that makes that possible to pass that legislation. So it helps the Republicans in that regard that the nation is divided.

13:17 Blackmon: Yea, so it’s another argument for that if you if you simply refuse to be a part of a decision-making process then you may well in fact just allow it to be decided for you.

Gallagher: Get the opposite of what you want. So there’s another at least thin rope connecting then to now

13:32 Blackmon: And so what we’ve seen over these last eight years has been more a version of we’re not gonna, we’re not gonna take our marbles and go home, but we’re going to hold on to our marbles and just sit here. We’re not going to do any trading and nothing is really going to happen and then we’re going to be very frustrated that a president begins to attempt to expand his executive powers and rule more by fiat.

Gallagher: And if you want another way to tie that position to now I mean Lincoln’s use of executive power was breathtaking in some ways and deeply offended even some in his own party as being inimical to civil liberties. I mean his suspension of the rite of habeas corpus. He did a number of things. He said, well, we need to do these. We’re in a crisis. I’m a president. I have these powers according to this. They argued about those things too then just as we do now. Did he exceed his powers? Many in his party thought so. In the end, Congress ratified everything he did. Congress wasn’t in session in the early part of this crisis.

14:30 Blackmon: The other not just a thread but the thick rope that connects that period and this period also ties into this current debate that we’ve had going on very hotly in the past couple of years around the images of that time and the symbols and the iconography of the confederate era. There were people who were bothered that the, that for a long time that southern states continued to fly the flag or had the confederate battle flag on their state flag and such. That issue had some emotion but the monuments were a confederate generals and battlefields were sort of accepted or not thought much about by a lot of people. What’s the broader reason for that in your view?

FACTOID: The Question: Should confederate symbols remain in public spaces?

Gallagher: Well I think the, I separate the flag from the monuments. I think the flag has no place in any governmental building or at any level, local, state, national. I think it should not be there.

Blackmon: Why is that?

Gallagher: Well, I just think it sends the wrong message. Why would it be there? Why should it be there? I has nothing to do with now. It’s an artifact from history and a deeply divisive artifact from history so why? And the only state I mean there’s still actually Alabama’s flag and Florida’s flag are still basically the St. Andrew’s cross but the one that really is obviously the confederate flag is Mississippi still and I’m sure they will revisit that ah as a state. So put that aside. The monuments I think have come back to the fore because they are way into other issues. I don’t think the monuments are the main issue that people are worried about. I think that they use the monuments to start a conversation about all kinds of other things that they are really interested in. That’s my own take on it. Everybody doesn’t agree with that but I think that’s what’s going on and I think that these periodic eruptions about the monuments go back, it’s sort of like groundhog day for me. I mean they come up and I’ve seen it many, many times in many places on university campuses and elsewhere and the arguments are usually the same on each side. So there’s a sameness there. I could script both arguments pretty much for them. But here, I think this time they seem to be tied to I think broader issues of inequality and broader issues relating to both economics and social things that are brought up after the flash point of the monuments provides the opportunity to do so.

16:55 Blackmon: And so that complicates the argument that is it heritage or is it hate today because in some sense ah many of these monuments particularly those that, or ones that have inscriptions on them that say things that are problematic by today’s standards you know to those who died in defense of the greatest society there ever was.

Gallagher: Absolutely.

17:16 Blackmon: And so you have this combination of yes on the one hand it is history and it is heritage of a certain group of people. On the other hand there is an embedded --

Gallagher: I don’t’ even throw in heritage. From my perspective forget heritage. From my perspective it’s history and I oppose taking down monuments. I believe, I use these monuments for lost cause tours that I give that get at not only the Civil War but memory and the 20th century. I think sanitizing the past is a mistake. I think it’s absolutely essential to confront our past including the biggest warts in our past. And I think these help us do that. The heritage argument I mean there that’s I have no patience with that. It’s but I’m wary of starting down a road where you pull down monuments because I think that could go in directions that many people would be very troubled by.

18:09 Blackmon: But then let’s also curate what is there. I mean because in some sense (Gallagher: Yea, I agree with that,) Yea, explaining. Because it is true that every time a government worker goes out to the confederate monument in front of the court house anywhere and sweeps the leaves away from the base of it there’s a little expenditure of the public’s funds that go into the preservation of that monument. And, in a sense, it’s a reexpression of the speech of that monument. That it’s being taken care of and kept there over time. And so it does seem logical to me that another part of the solution might be simply that there might be some sort of a well thought out way to put a sign up or something that says here’s why that monument is here.

Gallagher: I agree completely. I agree completely and I know and I I have had long and very friendly and useful discussions with good friends who simply have a very different view than I do on this. They believe the monument should come down. And I understand that perspective. I just think it’s more important to keep them because I think if you get rid of all of them then it’s pretty easy not to talk about that at all. And I don’t think we should stop talking about that.

19:17 Blackmon: And the city of New Orleans’s for instance has gone further than anyone else. Actually voting to remove a in a place that was a citadel of not just during the Civil War but became a real center of confederate remembrance in the years after the war. And so it’s really a radical thing for the city of New Orleans.

Gallagher: And it’s a really big monument. The Lee one there is huge. But it’s now being litigated of course. And that would happen in many of these places I think. Nothing, all of this is very complicated and the memory is complicated, the uses. We have we like simplistic understanding of the past. Who are the good guys? Who are the bad guys? And it’s never, it’s always complicated. Which is one argument to those who want to take down the monuments. They say it doesn’t matter what kind of explanatory text you put up around them. The key thing is that the Robert E. Lee statue is still there.

20:10 Blackmon: Yea, that that’s the that’s the Nazi statue argument.

Gallagher: The Nazi statue argument.

Blackmon: We wouldn’t tolerate Germany leaving up a, still hanging a giant swastika over a stadium in Nuremburg so why would we tolerate that eternally? What do you think about that when people draw to that?

Gallagher: I have no patience with that whatsoever. The confederacy is not Nazi Germany. It just isn’t. If the confederacy is Nazi Germany than what is Nazi Germany? People make easy illusions. Oh that’s just like the Nazis. No it’s not just like the Nazis. If it’s just like the Nazis we need to come up with new names of what the Nazis were because they were doing things that the confederacy was not. It’s, it’s, I don’t like those analogies. They don’t work for me.

20:53 Blackmon: And that’s an important role for an historian to play. That there are, that these overdrawn parallels can be just that and particularly the idea that, I get frustrated with the frequency with which people will sometimes say that something that is happening today is the same thing as slavery. Or . . .

Gallagher: Just like slavery. No it’s not. I talked about that in class this morning. It’s not just like slavery. You cannot sell my children. That’s slavery. You cannot tear my family apart, sell my children, no it’s not. Jim Crowe was terrible. Jim Crowe denied humanity in many ways to people. Certainly equal rights. It is not just like slavery. It’s not.

Blackmon: And slavery is not genocide.

Gallagher: It’s not. That comes in, I don’t want to belabor this, but the confederacy does not have wide scale efforts to exterminate people which Nazi Germany does. Slavery is a brutal institution. But it’s point is, the, they make money from it. They don’t want to destroy the institution they’re making money from. So you just have to separate Nazi Germany from the confederacy. You just have to.

22:05 Blackmon: Let’s go back to where we began this whole episode and that was this taking note of this incredibly divided time that we are, have in American life this presidential election that really is about very serious things. It is hugely affected by the sense of division by the country, a sense of political bitterness but it is also about very substantive different views about how the American economy should evolve over time. Maybe more fundamental questions than we’ve seen in a presidential election in quite some time. So President Obama, quite famously, when he came into office publicly discussed his reverence for Lincoln and he wanted to evoke the Team of Rivals, the title of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book about Lincoln and in the end was teased a little bit about whether he really was as Lincolnesque as he imagined whether he really did pull of a team of rivals. But so if you were sitting down with whoever the next president is and you were going to say as you approach this even more now divided time and you were trying to reach back to the era of Lincoln for some lessons that would have value today, what would you reach back to? What would you say to that new president?

Gallagher: Well the first thing I would do is not compare myself to Lincoln. That’s the very first thing I’d do because that’s generally a losing proposition. But what I would do is identify what the principal problem that you’re going to be dealing with is. Lay it out. And then I would bring into the effort to deal with that leading figures who may not agree with you. That’s what the Team of Rivals were. You had a very conservative Edward Bates from Missouri, you had William Henry Seward, Salmon P. Chase much more liberal than Lincoln on the question of emancipation for example. Bring these different voices, these clashing ideas in some ways to the process of dealing with what you have identified. This is what I’m going to deal with. And it is so serious that I’m going to reach out to people I know disagree with me in some ways and we’re going to find a way to make this better. And in Lincoln’s case it was put the Union back together. The next president is going to face the kinds of things you said. Let’s send a message to the people of the United States that you’re so serious that you are actually going to tolerate ideas different than those you hold yourself in an effort to find a solution.

24:19 Blackmon: The case has been made by some historians of the presidency and such that truly great presidents can only occur in the context of a great crisis, and so that if a president doesn’t face a gigantic crisis, then they will never emerge as a truly legendary sort of president. But so , it’s impossible to imagine this in reality, but if Abraham Lincoln had somehow had not had the Civil War to contend with, what kind of president would he have been?

Gallagher: I don’t he would be to us what he is now. Because it really is the threat to the very existence of the nation that lets Lincoln be the towering figure that he is. I think that’s right. The only president who’s a great president who didn’t face a specific crisis was Washington, and there, everything he’s doing is setting a precedent, so he’s in an entirely different category. But other than Washington? All the other ones who are reckoned great dealt with a tremendous crisis.

25:17 Blackmon: Gary Gallagher. Thanks for joining us.

Gallagher Enjoyed it. Thank you.

25:20 Blackmon: We hope you’ll join this conversation with American Forum on the Miller Center Facebook page, or by following us on Twitter @douglasblackmon or @americanforumTV. To send us a comment, watch other episodes, download podcasts, get a transcript or to read more about the most important first year challenges that have faced many presidents in the past, visit us at millercenter.org/americanforum. I’m Doug Blackmon. See you next week.