It is not that close. This does not have to be a political crisis.

It is time to begin a peaceful transfer of power, writes Miller Center Director William Antholis

We have just completed a narrow, hard fought election. Given the ongoing economic crisis and pandemic, the country should begin the peaceful transfer of power.

President Trump has indicated he will pursue legal challenges to the election results. But the chances of a recount flipping tens of thousands of votes across multiple states in his favor are outside anything we have seen in American history.

When compared with other close elections, this one is actually quite a comfortable victory for President-elect Biden. The Biden-Harris ticket has won or is significantly ahead in states worth 306 electoral votes.

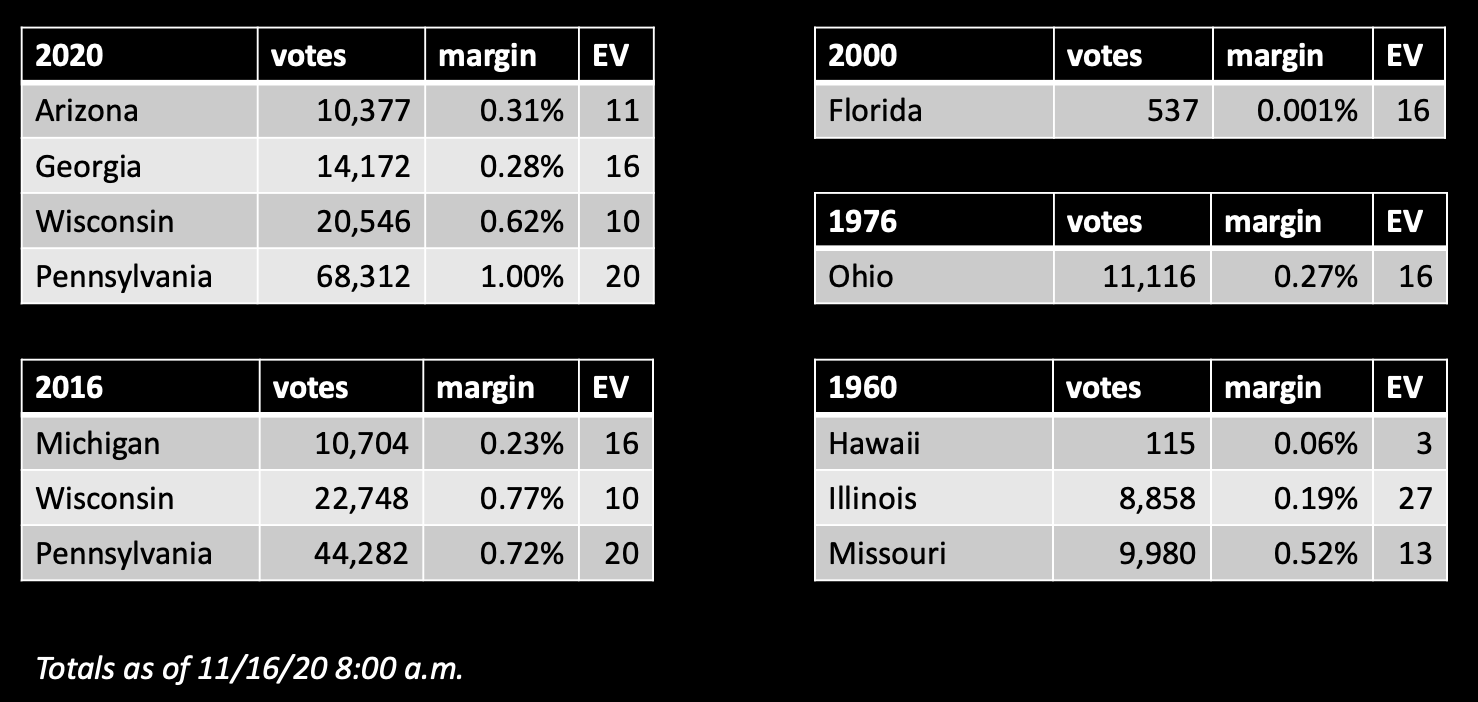

For Trump to win, he must flip at least three of the four narrowest margins of defeat, where he either must persuade courts to disqualify tens of thousands of ballots or have recounts overturn results in three of the four closest “tipping point” states that put Biden over the 270 threshold.

The margins of victory in the four tipping point states are quite similar to those which President Trump won in the 2016 election, when he garnered 306 electoral votes in a mirror image of this year’s election.

His margins of victory were slightly larger in 2016 than Biden’s are in 2020, but Trump must go deeper down the list to collect enough electoral votes to reverse the outcome.

Past recounts have changed hundreds of ballots, but typically not thousands. According to a study by FairVote, only twice since 2000 have recount vote swings been greater than 1,000. Both happened in 2000, when Al Gore picked up 1,247 votes in the Florida presidential race, and a statewide race in Colorado reversed 1,121 votes. Between 2000-2015, the median swing was just over 200 votes—often in favor of the candidate in the lead.

The country has seen much closer elections than the current one. The two most famous “contested elections” were in 2000 and 1876. The 2020 election was not as close as either.

In the 2000 Bush-Gore race in Florida, one state alone would have decided the outcome, leading to nearly two months of recounts and court battles. By comparison, President-elect Biden’s narrowest lead is more than 11,000 votes in Georgia, which is over five times larger than Bush’s initial Florida lead of 1,784.

The country has seen much closer elections than the current one.

In the 1876 election, pitting Rutherford Hayes against Samuel Tilden, narrow margins in South Carolina (889), Florida (922), Oregon (1,057), and Louisiana (4,807) led to a four-month stalemate. A special commission investigated charges of fraud or voter disenfranchisement, and ultimately declared Hayes the winner in a deeply partisan 8-7 vote.

The 20th century has seen two other elections much closer than Biden-Trump. Neither became a political crisis. In 1976, Jimmy Carter defeated Gerald Ford by winning a single tipping point state, Ohio, by 11,116 votes, or 0.27%. Coming after the national trauma of Watergate, Gerald Ford conceded the next morning.

John Kennedy’s 1960 victory over Richard Nixon had narrow margins in Hawaii (115), Illinois (8,858), and Missouri (9,980), which all would have needed to be reversed to give Nixon the election. Nixon conceded the next morning.

If the 2020 election becomes a political crisis, President Trump will have created one. The only analog would be the self-created crisis of 1860. Then, Abraham Lincoln won the electoral vote and a plurality of the popular vote with no evidence of fraud or illegality. The losing side, Southern Democrats, could not accept the legitimacy of the outcome. Seven states seceded from the Union between Election Day and Inauguration Day, triggering the Civil War

Does 2020 constitute a political crisis? Not by itself. And not yet. States will begin to certify the results. But if the president continues to question the legitimacy of the vote beyond where the facts and odds justify, it could lead to great danger for the American people.

If the 2020 election becomes a political crisis, President Trump will have created one.

Transitions amidst crises of any kind are inherently dangerous moments. The government’s power to defend and protect America is only as good as the public’s faith in our institutions and our leaders. For more than 200 years, we have peacefully transferred power from one president to another.

A political crisis would compound the two other crises we face. Leadership on the pandemic is necessary and urgent, as daily deaths are now matching levels from April and May. The economic crisis, brought on by the pandemic, has still left 11 million people out of work. Congress and the White House failed to offer emergency relief prior to the election, as the winter and flu season approach.

Moreover, national security transitions are complicated and dangerous. Presidential first years are notorious for foreign policy crises and mistakes. The list is long and painful – from the Bay of Pigs in 1961, to Black Hawk Down in 1993, to the 9/11 terror attacks. It is hard enough in normal times for a new president and a new team to prepare to confront the threats facing the nation.

This does not have to be a political crisis. The election was not historically close. President Trump can claim victory for his policy accomplishments and devote the considerable power of a post-presidency to advancing his priorities.

The alternative would be the first sitting president to challenge the legitimacy of our democracy. In short, he would be doing what the South did in 1860. We cannot repeat that mistake.