Election 2020 and its aftermath

University of Virginia Institute of Democracy experts offer frequent updates on the latest developments

VISIT ‘THE BIDEN ERA BEGINS’ FOR NEWER POSTS

This effort is made possible thanks to the generous support of the George and Judy Marcus Democracy Praxis Fund

NOT A NORMAL TRANSITION

President-elect Biden attempts to project an air of calm confidence even as the coronavirus surges and his transition is delayed. The latest from UVA Institute of Democracy experts.

November 17, 2020

Today's posts

Why the transition matters • Melody Barnes

Melody Barnes, co-director of UVA's Democracy Initiative and a Miller Center professor of practice, joins CBC to discuss the latest on the transition to a Biden administration.

THE COSTS OF DELAY

The president-elect moves forward, but what are the risks of continued conflict about the results of the 2020 election?

November 16, 2020

Today's posts

Transition troubles, 1968 • Marc Selverstone

Vaccine distribution and a turbulent transition • Margaret Riley

If the president won't concede • Chris Lu

Homeland security risks • UVA Today

Presidential transitions are among the most sacred yet precarious of moments in the American political lifecycle. The peaceful transfer of power from one administration to another has been a core principle of American democracy for well over 200 years. But transitions are also moments of inherent instability, with one set of officials heading for the exits and another one hitting the on-ramps. While outgoing and incoming administrations have long endeavored to effect smooth handovers, any number of developments, from the personal to the political to the geopolitical, can make it a perilous process.

Transitions are moments of inherent instability.

As such, transitions involve a delicate dance in the best of circumstances. But transferring power amidst ongoing and intersecting national crises magnifies the challenge of ensuring effective governance and promoting the national interest—even more so when the change involves a transfer of power from one party to another.

The presidential transition of 1968 was one such moment. It took place against the backdrop of several shattering developments that year: the Tet Offensive and a deeply divisive war in Vietnam; the withdrawal of President Lyndon B. Johnson from the presidential race; the assassinations of civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. and Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Robert F. Kennedy; civil and racial unrest throughout the nation; and violent altercations at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. To many Americans, the nation seemed to be unraveling.

For Lyndon Johnson, who soon would vacate the Oval Office, the transition also came with the knowledge that President-elect Richard M. Nixon, in late October, had sabotaged the start of peace talks in Vietnam, and with it, the possibility that Democratic candidate Hubert H. Humphrey—the sitting vice president—might benefit and win the presidency. Johnson was livid, but he sat on the information rather than leaking it, fearing a host of troubles that might flow from that disclosure. Nixon was thus able to hang on, claiming 301 votes in the Electoral College to Humphrey’s 191, but winning only 43.2 percent of the popular vote to Humphrey’s 42.7 percent (third-party candidate George Wallace garnered close to 14 percent).

To many Americans, the nation seemed to be unraveling.

Nevertheless, the transition seemed to be proceeding apace. Nixon told Johnson, in a conversation captured by LBJ’s White House taping system, that he appreciated the cooperation he was receiving from Johnson personnel. And Johnson told Nixon what he had earlier said to Reverend Billy Graham and Nixon friend Sen. George A. Smathers [D-Florida]: “that I would try to be as least—less partisan as I could and still be head of my party and be president, and I will try to be as helpful as I could when the inevitable happened, and we’re going to do that, and you’ll see that."

Listen to and read the full transcript of this call at the Presidential Recordings Digital Edition

So when Nixon briefed journalists just hours later on November 14 that he not only needed to be “informed” of U.S. policymaking during the transition but that he “agree” to any proposed “courses of action,” Johnson got his hackles up once again. The United States, Johnson told Nixon aides and Nixon himself, had only one president at a time. Still, there was a transition to manage, with the whole world watching. As the two principals acknowledged that morning, it was important that the outgoing and incoming teams be aligned, since the Soviet Union would

take advantage of you in an electoral period. They did in the [Dwight D.] Eisenhower-Nixon administration, in Laos, before [John F. “Jack”] Kennedy could get sworn in. [Nixon acknowledges throughout.] They did in ‘62 in the Cuban Missile Crisis; October the 22nd, they moved. Now, they think we’ve got a gap.

But Nixon’s statement threatened to tie Johnson’s hands. According to Nixon, he simply wanted to emphasize that “any major policy decision that has to be implemented by the new president, the old—the previous adminis—the present administration would want to clear it with the new administration to be sure it would be implemented.”

Johnson was having none of it. As he told the President-elect, “I’m very fearful if we leave the impression in the world that we have to check with [transition liaison Robert D.] Murphy or with you before we make a decision that we’re going to leave the impression we’ve got two presidents operating.” And just so audiences at home and abroad got the message, Johnson spoke to reporters the following day, affirming that “I will make whatever decisions the President of the United States is called on to make between now and January 20th.”

Listen to and read the full transcript of this call at the Presidential Recordings Digital Edition

With that, that contretemps came to an end. But it highlights the recurrent challenge of policymaking during the interregnum, as well as the novelty of our present moment. For all of Nixon’s malfeasance both then and later, and Johnson’s legitimate concern about an election that might have been improperly swayed, if not stolen, both sides pursued the time-honored and solemn tradition of transferring power in a professional, orderly fashion, with the nation’s interests in mind. Remarkably, the presidential transition of 1968, from the perspective of 2020, seems almost quaint.

—Marc Selverstone, chair, Presidential Recordings Program, Miller Center

With Moderna’s announcement this morning that preliminary results demonstrate that its vaccine is 94 percent effective, the nation now has two highly effective vaccines that could begin to be handed out by the end of the year.

That means distribution is about to begin during one of the strangest presidential transitions in modern times—and questions abound about how the Trump administration might politicize it. This is already evident in President Trump’s remarks on Friday. Somewhat inaccurately taking credit for the Pfizer vaccine, Trump could not resist a dig at Andrew Cuomo, putting into question how some Blue states might be treated in the vaccine rollout.

It is also not clear whether the incoming Biden administration will be provided any official information on the process. In addition, Operation Warp Speed, which will be responsible for the logistics, is heavily controlled by the Pentagon, and a major shake-up at the top of that agency, with Trump loyalists taking charge, adds to the concerns.

The Trump administration, however, is somewhat in a bind. It no doubt wants to take credit for the vaccines (and in fairness, it deserves some of that credit), so sabotaging the initial rollout during December and early January makes no sense. And many of the distribution plans are already in place and public.

The Pentagon logistics are under the control of four-star general Gus Perna, a career military officer likely to be able to sustain the political gamesmanship of the next few weeks.

Pfizer and Moderna also have every incentive for a smooth rollout. CDC published a full “playbook” for the rollout at the end of October. Even the incoming Biden administration has plenty of backchannel means of obtaining information. The biggest difficulty, however, is likely to be obtaining the funds for the cash-strapped states to train the individuals who will actually be storing and administering the vaccines and keeping the necessary records.

None of the states have close to sufficient funds for that, and without those funds, the distribution of the vaccine could descend into chaos, leaving the Trump administration to take victory for the production of the vaccine while weakening the Biden administration’s management of the subsequent steps.

—Margaret Riley, professor of Law, UVA School of Law; professor of Public Health Sciences, UVA School of Medicine

Chris Lu, a Miller Center senior fellow who ran the Obama transition in 2008–9, discusses how this

year's unsettled transition affects the incoming Biden administration—and Americans. "We have had presidential transitions for over 200 years in this country," Lu told host Jen White. "We've done it through war and depression and even when the two people on either side of the transition fought a bitter campaign. So this has always happened, and it needs to happen well. We're talking about the turnover in leadership of the U.S. government, which is the largest, most powerful organization in the world."

A peaceful and prompt transition of power is crucial to both the health of American democracy and the nation’s security, Janet Napolitano and Michael Chertoff said Friday in a webinar hosted by the University of Virginia’s Institute for Democracy and the Miller Center.

They would know. Chertoff served as secretary of homeland security under President George W. Bush from 2005 to 2009. He oversaw the department’s handoff to Napolitano, a UVA School of Law alumna who served as secretary of homeland security under President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013.

“Having a transition that begins right away, getting security clearance to the incoming team, giving the president-elect access to current intelligence – these are all part of the process of preparing, so that when a new administration comes in, they can hit the ground running and not have to figure out what the threats are and what the capabilities to respond are,” Chertoff said.

In addition to Napolitano and Chertoff, Friday’s webinar included David Marchick, director of the nonpartisan Center for Presidential Transition at the Partnership for Public Service, and moderator William Antholis, director and CEO of UVA’s Miller Center for Public Affairs. It was sponsored by the UVA Institute for Democracy, the Center for Presidential Transition, and Citizens for a Strong Democracy, a nonpartisan organization that Napolitano and Chertoff founded with two other former secretaries of homeland security.

Antholis began the webinar with a question about the process of “ascertainment”—a legal process by which the General Services Administration gives the president-elect access to resources and classified information needed during the transition from one presidential administration to another. That process is mandated by the Presidential Transition Act to begin once the results of the election are clear. As of Friday, Emily Murphy, head of the General Services Administration (and a UVA Law alumna), had not yet signed that paperwork.

“The issue of ascertaining the winner of the election [in the GSA] has never been controversial or politicized,” Marchick said. “Many other government agencies have similar responsibilities to act when there is a new president-elect. The Secret Service, for example, expanded its protection around Joe Biden. That is not politicized; the Secret Service just did it. Unfortunately, even the most noncontroversial ministerial acts are being politicized today.”

[E]ven the most noncontroversial ministerial acts are being politicized today.

David Marchick

The nation experienced a similar delay in 2000, when the ascertainment process was delayed due to recounts in Florida that eventually determined the winner of the presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore. That election was closer than this one, Marchick said, noting that this time, he believes “the outcome is clear.”

Chertoff, who came in with the Bush administration, said the 2000 delay hurt the administration’s ability to respond to national security concerns, especially because it took longer to complete the Senate confirmation process for key positions. The gap became especially apparent during the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

“I was in the Department of Justice on 9/11 and we were shorthanded in senior people, so that we had to essentially do double- and triple-duty to pick up responsibilities that normally would have been taken by others who had been confirmed,” he said.

Napolitano also stressed the importance of a smooth handoff, recalling how, after their own turbulent transition experience, Chertoff and the entire Bush team made it a point to help their successors as much as possible.

“I was then serving as governor of Arizona, and could not fly back and forth frequently to Washington,” she said. “Michael sent leadership from the Department of Homeland Security out to Phoenix, and they had extensive briefing materials prepared for me and my team.

“I give President Bush credit for this. He set the tone and direction for a cooperative transition, and I think it was the gold standard of presidential transitions. President Obama gave the same direction to his administration, and used the Bush transition as an example, but unfortunately many members of President Trump’s team did not take him up on it.”

Watch the event

ASSESSING THE RISKS

Biden wins Arizona. DHS declares the election secure. There's turmoil at the Department of Defense. UVA institute for Democracy experts examine the implications.

November 13, 2020

Today's posts

A presidential transition delayed • Kathryn Dunn Tenpas

Stacey Abrams, power broker • Barbara Perry and Alfred Reaves IV

Arizona's Hispanic vote • Cristina Lopez-Gottardi Chao

Trump puts lives at risk • Melody Barnes and Kathryn Dunn Tenpas

Pentagon purges raise major concerns • William Antholis

Miller Center senior fellow Kathryn Dunn Tenpas looks at the risks of a delayed transition on Politics with Amy Walter from PRI and WNYC.

If after Georgia completes its recount, Joe Biden is still ahead of Donald Trump, the former vice president and president-elect will owe Stacey Abrams a major debt of gratitude for improbably flipping the Peach State from blood red to pale blue, at least at the presidential level.

Although Abrams lost the 2018 Georgia governor’s race, her losing margin of only 1.4 percent and the specter of voter suppression energized the former state legislator to mount an activist campaign to register and turn out voters, especially African Americans. Abrams founded Fair Fight Action, a grassroots interest group, to combat the stifling of Black votes in Georgia and Texas. Her movement, in concert with other activist organizations, galvanized the ground game in Abrams’s home state, where some 750,000 new voters registered.

Georgia had not selected a Democratic presidential candidate since Arkansan Bill Clinton’s 1992 successful White House bid. This year, 59.3 percent of first-time voters in the Peach State voted as Democrats, while 35.9 percent cast their ballots as Republicans. Clearly, this difference helped to account for Georgia’s placement in the Biden-Harris column.

While leading the battle for voting equity, Abrams has become a national icon and best-selling author for her book, Our Time Is Now: Power, Purpose, and the Fight for a Fair America. It echoes a previous female Democratic Party power broker, Eleanor Roosevelt, whose last tome, published posthumously, was titled Tomorrow Is Now. How appropriate that this latest king-/queen-maker in the Democratic Party both follows in the footsteps of ER and blazes a wholly new trail—one that can only be forged by an African American woman.

The contemporary team of Abrams and vice-president-elect Kamala Harris can utilize their mandate to achieve the policies long fought for by generations of black women who have reliably supported the Democratic Party since the New Deal, but without due recompense.

—Barbara Perry, Gerald L. Baliles Professor, director of Presidential Studies, Miller Center

—Alfred Reaves IV, faculty and program coordinator, Miller Center

Last night, Arizona tilted in Biden’s favor—a development that flipped the state blue for the first time in almost a quarter century. Similar to 2016 when Trump won Arizona by just 3.6 percentage points, 2020 saw an even tighter race, with Biden taking the lead 49.4% to Trump’s 49.1% as of this morning. Given the state’s large Hispanic population—estimated at just over 23% of the state’s eligible voters—it’s useful to consider how this cohort may have affected 2020 outcomes.

According to the Washington Post, Biden won 63% of Arizona’s Latino vote, compared to 36% that went to Trump. This differs significantly from Trump’s Latino support in Florida, where roughly half of Hispanic eligible voters supported him. But the makeup of Arizona’s Latino share differs significantly from the sunshine state whose Hispanic majorities include Cuban Americans and Puerto Ricans.

The makeup of Arizona’s Latino share differs significantly from the sunshine state whose Hispanic majorities include Cuban Americans and Puerto Ricans.

According to 2014 Pew data, the large majority of Arizona Hispanics—over 87%—originate from nearby Mexico, with the next largest cohort coming from Puerto Rico (but they account for less than 3% of the state’s total Latino electorate). And Mexican Americans tend to lean towards the Democratic party, perhaps influenced in part by the state’s tough immigration laws, particularly Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070 and its “show your papers” provision.

But as Professor Gerardo Cadava aptly points out, understanding the Latino vote is not always a straightforward calculation. He writes, “There's a real diversity of political beliefs, and we need to acknowledge that Latinos are fully human, complicated political actors, rather than just kind of pawns that are easily poached or persuaded, just because a politician talks to them.” Cadava studies Hispanic Republicans, particularly those in the Sun Belt, and he points to Trump’s (and the GOP’s) understanding that many Hispanics prioritize economic individualism, religious liberty, and law and order, all values that align with the conservative movement. So assessing their views in a state like Arizona, while a majority of Mexican Americans lean left, can be a complicated task.

This year Latinos were projected for the first time to be the nation’s largest racial or ethnic voting minority—representing 13.3% of the total U.S. electorate—a trend that will continue to affect elections outcomes in the future. And while turnout has been a challenge for Latinos in the past, early estimates indicate that 2020 may have changed that. As we continue to dissect this year’s election results, both parties would be wise to pay attention to this cohort, its many subsets, its seeming contradictions, and the differences between Hispanic voters in each state. One thing is certain, party messaging to Latinos should not be uniform.

—Cristina Lopez-Gottardi Chao, assistant professor and research director for public and policy programs, Miller Center

This complete op-ed appeared in the Washington Post

It is now 10 days since Election Day and nearly a week since the networks declared Joe Biden the president-elect. Nevertheless, Emily Murphy, the Trump appointee who controls transition funding and permits access to senior officials across the government through her post at the top of the General Services Administration, has refused to “ascertain” the winner of the presidential election. There is no question that she is facing pressure from the White House to stand firm, but her intransigence threatens our centuries-old commitment to a peaceful and efficient transfer of government.

Her actions effectively truncate an already brief transition period (78 days), breaking long-established norms about how a losing president concedes and helps the incoming administration prepare to run the government. The issue is even more grave since the country is struggling to defeat a pandemic, which is getting worse as cases and hospitalizations hit record levels. And the fallout will be tremendous — affecting every sector of the economy as well as ratcheting up the level of emotional turmoil and trauma.

Murphy’s reluctance denies Biden’s incoming White House aides critical resources: additional funding to pay for transition expenses (e.g., salaries, supplies, travel), the acquisition of additional office space, advancing the vetting of potential nominees through the FBI and, perhaps most important, access to the civil servants who have prepared extensive reports in preparation for this very moment. The ability to interview outgoing appointees as well as civil servants is fundamental to the successful transfer of power.

—Melody Barnes, co-director for policy and public affairs, UVA Democracy Initiative; Professor of practice, Miller Center

—Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, senior fellow, Miller Center

President Donald Trump's Monday firing of Secretary of Defense Mark Esper was only the beginning of major changes at the the Pentagon. In addition to replacing Esper with Christopher Miller, the president appointed Anthony Tata to replace James Anderson, who had been acting undersecretary for policy. Joseph Kernan, a retired Navy vice admiral, stepped down as undersecretary for intelligence and was replaced by Ezra Cohen-Watnick. Kash Patel becomes Miller's chief of staff.

"The Pentagon purges are most troubling because there are two months remaining,” the Miller Center's Director and CEO William Antholis, told Susan Glasser of the New Yorker. Is the president making major policy changes, or simply feeling free to indulge his feelings in the wake of a disappointing election?

FRIDAY SPECIAL EVENT: TRANSITION IN TIMES OF CRISIS

Two former Secretaries of Homeland Security look at the consequences of a fraught transfer of power.

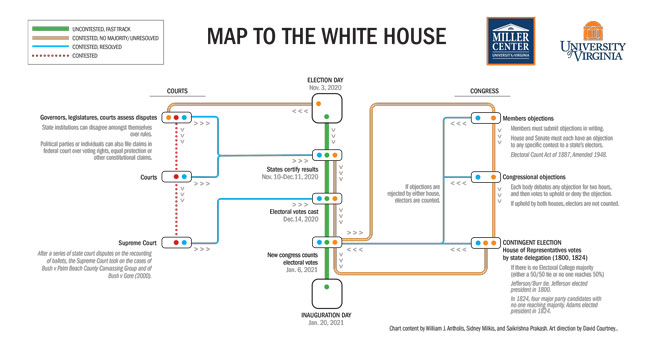

The Presidential Transition Act was adopted by Congress in 1963 to provide an important statutory framework for the peaceful transfer of power. Watch this discussion with former secretaries of homeland security and transition experts on the importance of a peaceful and effective presidential transition to ensure America's safety and security.

Secretary Michael Chertoff, who served under President George W. Bush, oversaw the transition of the department to Secretary Janet Napolitano, who served under President Barack Obama. They are among four former homeland security secretaries who came together to create the nonpartisan Citizens for a Strong Democracy to focus on election integrity and to support a secure presidential transition.

The discussion wasmoderated by William Antholis, director of the nonpartisan Miller Center for Public Affairs at the University of Virginia, and David Marchick, director of the nonpartisan Center for Presidential Transition at the Partnership for Public Service.

This event was co-sponsored by the Miller Center, the Partnership for Public Service's Center for Presidential Transition, and Citizens for a Strong Democracy. It is made possible thanks to the generous support of the George and Judy Marcus Democracy Praxis Fund.

Watch the event

DEALING WITH REALITY

Coronavirus surges, the economy struggles, and election litigation continues. UVA experts look at the latest news.

November 12, 2020

Today's posts

Transition vulnerability • Kathryn Dunn Tenpas

Our democratic culture is at risk • Melody Barnes

The first "second gentleman" • Barbara Perry

Clearly our enemies can see that vulnerability.

Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, a Miller Center senior fellow, took stock of the fraught transition to the Biden presidency for USA Today. Though President-elect Biden says his team doesn't need the access it has so far been denied, Tenpas suggests problems could arise, threatening his first weeks in office. "This strikes me as a matter of the country's reputation internationally and being so vulnerable. The whole world is watching and clearly our enemies can see that vulnerability," she said. "So the question is do people try to take advantage of that?"

Melody Barnes, who served as director of the White House Domestic Policy Council under President Obama, is now co-director for policy and public affairs for UVA's Democracy Initiative and a Miller Center professor of practice. She joined MSNBC's Joy Reid to discuss the risks to our democracy from the polarizing 2020 election.

Barbara Perry, the Miller Center's director of Presidential Studies, talked with the Guardian about Kamala Harris's husband, Doug Emhoff, who is poised to assume the role of vice presidential spouse. “A good sign that someone is a good campaigner is when he or she is sent out alone and doesn’t have to go with the spouse or the family member," said Perry. "That was the secret to the Kennedy family.”

“We tend to put women who’ve been in these roles in these boxes, and we don’t let them beyond a certain limit,” she added. “And it will be interesting to see how we treat Doug Emhoff. Will the difference in gender allow him to do more?”

Interestingly, it was soon-to-be First Lady Jill Biden who may provide the best comparison. “She continued to teach and be a professor while she was second lady for all those eight years,” said Perry. “Between the two of them as non-traditional spouses, will they form a new paradigm for both first lady and second gentleman?”

TRANSITION AMIDST CRISIS

President-elect Biden and his team face obstacles as they prepare to lead. Here's what UVA Institute of Democracy experts have to say.

November 11, 2020

Today's posts

The new Confederates • Sidney Milkis

Exit Poll Nuggets™: Traits that mattered • Jennifer Lawless and Paul Freedman

Biden faces immediate tests in Asia • Evan Feigenbaum

A tenuous time • Chris Lu

Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural address, delivered after an election that put the Union on the brink, called for the Southern states to resist the vanguard of the Confederacy—South Carolina, which had already seceded—and stay in the Union. “We are not enemies, but friends,” Lincoln pleaded in his famous peroration. “We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

These words were echoed by president-elect Joe Biden in his address to the nation last Saturday evening. Alas, like Lincoln’s entreaties, which were fiercely rejected by the 11 states that joined South Carolina in declaring themselves restored to a “separate and independent place among nations,” Donald Trump and most Republicans in the House and Senate have spurned Biden’s peace offering. Without any evidence, the president and his top advisors claim that voting fraud has taken place on a large scale, and that the election was “stolen.” Most Republicans have not gone that far, but they have backed the president’s adamant refusal to concede, in some cases amplifying his baseless claims that he won the 2020 presidential election. This election thus marks the first time since 1860 that the losing candidate and his followers have refused to accept the verdict of a presidential election.

We can hope that this resistance is temporary—that, as the press has hinted, the president’s followers are trying to coax him along to accept the inevitable. But the many comparisons that historians have made between the Civil War era and the present give us pause that presidential advisors and Republican office holders will do the right thing. Now, like then, a united and passionate minority of the nation is trying to protect its “way of life” from large-scale social changes and huge demographic shifts.

Now, like then, the nation is divided by the fundamental question of who deserves citizenship, fomenting major religious and racial divisions—the principal fault lines of American politics. Then, as now, the two tribes are encamped in distinct regions and counties that fundamentally distrust one another.

Our divisions, of course, are not as virulent as they were in the battle over forced servitude. Indeed, there were some promising, albeit very incipient, signs that racial and ethnic animosities were not as intransigent during the 2020 election as they were four years earlier.

Biden did slightly better in rural areas than Hillary Clinton; and Trump made some modest gains some among African Americans and Latinos. The “Cold Civil War,” as many pundits have described the present, need not conflagrate the nation. However, the president and his political allies have focused their indictment of voting fraud in diverse metropolitan areas like Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and Detroit, which, as Biden acknowledged in his victory-claiming address, provided critical support in key swing states.

The condemnation of my hometown, Philadelphia, which the president began demeaning in the first debate, has been especially egregious. “Bad things happen in Philadelphia,” he charged. In effect, the post-election battle for legitimacy is a postscript on the law-and-order trope that President Trump deployed against Black Lives Matter protesters in the months leading up to the election.

There is one telling, and disconcerting, difference between the old and new confederates. The states that seceded did not reject the verdict of the 1860 election. Their secession was not prompted by the perception that the campaign was rigged.

As South Carolina’s Declaration of Secession stated, the 1860 election was a clear sign, despite Lincoln’s reassurances, that their way of life, buttressed by the constitutional recognition of slavery, had “been defeated.” In fact, the integrity of elections was critical to Lincoln’s claim that the United States rested on popular sovereignty—that, as he put it in his 1859 speech, “Public opinion in this country is everything.”

The first president to face election during wartime, Lincoln insisted that free and fair elections must take place. By contemporary standards—in reality, not as high as our own—this was true of the 1862 midterm, in which Republicans lost their majority in the House. It also happened in the hard-fought 1864 campaign, where the popular Democratic candidate, General George C. McClellan—opposing the Emancipation Proclamation, which he claimed was preventing the South’s willingness to rejoin the Union—seemed to have the advantage in a nation tired of bellicosity.

Privately, Lincoln expressed fears that he would lose his reelection bid, but he accepted the risk and permitted his power to be threatened in a way he believed was required by the Constitution. When rumors spread during the campaign that if Lincoln was defeated, he would refuse to accept the verdict of the people, he responded at a public gathering in October.

The president insisted that he was “struggling to maintain the government, not overthrow it.” He then pledged that whoever was selected on election day would be duly installed as president on inauguration day—a course that was “due to the people, both in principle and under the Constitution.”

One does not have to be histrionic to fear that President Trump’s refusal to accept a peaceful transfer of power, through the campaign and during its troubling aftermath, might undermine the public’s faith in elections and damage president-elect Biden’s transition to the White House. Indeed, a large number of Trump voters have accepted their charismatic leader’s denial that the robust 2020 campaign, with the highest voter turnout since 1900, was legitimate. As Lincoln understood, public opinion can be capricious—demagogues might lead it astray by appealing to people’s worst instincts.

We can only hope that the Republican Party, if not the president, who claims to be the repository of its collective responsibility, will appeal, as Lincoln urged, to the “better angels of our nature.” For in the final analysis, the healing process that president-elect Biden urges the nation to begin might depend on Republican leaders in Congress and the States demonstrating that they represent more than the political ambitions of the president.

—Sidney Milkis, White Burkett Miller Professor of Governance and Foreign Affairs, Miller Center

Welcome back to the final (for now) installment of Exit Poll Nuggets™.

Today, we explore the candidate traits that mattered most to voters. As noted last week, in the immediate aftermath of a national election, exit polls offer the best glimpse of what the electorate looked like—who voted for whom and what seemed to drive their choices. In 2020, the exit polls combined interviews with a representative sample of thousands of voters (leaving polling places in precincts across the nation) and telephone interviews with a representative sample of people who voted early or by mail. In all, the national exit poll includes interviews with 15,590 voters. It is important to note that these data have recently been updated, and may continue to be updated. The numbers below reflect the exit polls reported as of Tuesday, November 10.

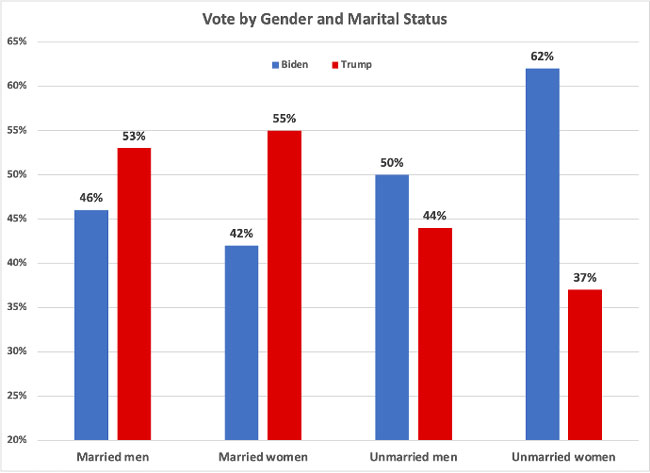

Issues vs. personal qualities: Nearly three-quarters of voters (74 percent) say that issues mattered more to them when deciding for whom to vote than personal qualities did. And Trump enjoyed a six-point advantage among those who said issues mattered more (53 vs. 47 percent for Biden). But of the 23 percent of voters who claim that qualities mattered more, Biden saw a 33-point advantage (64 vs. 31 percent). In an election that was quite close in multiple states, it’s fair to conclude that candidates’ personal qualities influenced the outcome.

Candidate favorability: Not surprisingly, voters are more likely to choose a candidate of whom they have a positive opinion. Ninety-four percent of those with a favorable view of Biden voted for him, and 95 percent of voters with a favorable view of Trump cast their ballots for him. Importantly, Biden had a clear advantage on this dimension: 52 percent of all voters had a favorable impression of Biden, while 46 percent had an unfavorable view. For Trump, the numbers were flipped: 46 percent favorable, 52 percent unfavorable. Thus, Trump’s favorability ratings were “under water,” with a six-point net unfavorable view among voters.

Temperament: Even more important than general perceptions of favorability were assessments of “temperament.” To be sure, this is a fairly broad characteristic (no specific definitions were provided). But voters saw a difference between the candidates: Fifty-four percent agreed that Biden has the temperament to serve as president, and 92 percent who expressed this view voted for him. In contrast, only 44 percent of voters agreed that Trump has the temperament to serve as president (just about the same as his job approval rating on Election Day). Although Trump received support from 95 percent of these voters, they represented a smaller segment of the electorate.

Mental and physical health: Beyond temperament, the exit polls also asked about voters’ perceptions of the candidates’ mental and physical health. Given that this election featured two senior citizens vying for the White House—both of whom have experienced health-related problems in the past—an overarching question of the entire cycle was whether either had the stamina to make it through a four-year term. Voters expressed a fair degree of doubt. They split right down the middle (49 percent vs. 49 percent) when asked whether Biden has the “physical and mental health to serve effectively as president.” The split was exactly the same when asked about Trump. It’s impossible to know based on the way this exit poll question was worded whether voters’ doubts had more to do with physical or mental health, but these concerns did weigh into vote choice. Ninety percent of voters who thought Biden was healthy voted for him, and 89 percent of voters who thought Trump was healthy voted for him.

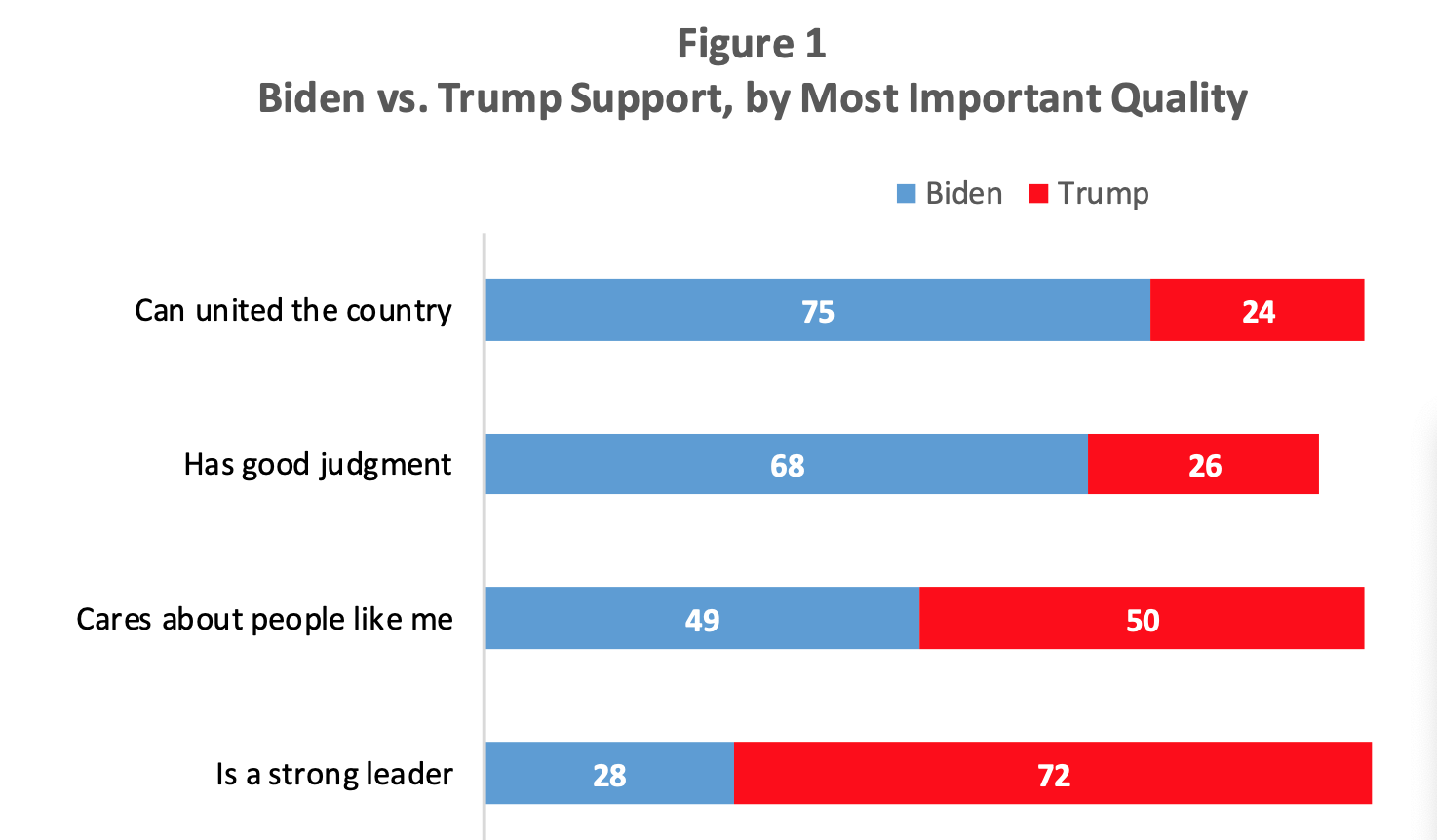

Most important quality: Beyond temperament, the exit polls presented voters with four candidate qualities and asked them which mattered most in their decision. Strong leadership topped the list, with 33 percent of voters identifying it as the most important quality. Good judgment (24 percent), caring about “people like me” (21 percent), and an ability to unite the country (19 percent) rounded out the list. Notice that Biden drew the overwhelming support of voters who prioritized unity and good judgment (Figure 1). Trump won voters who cared most about strong leadership.

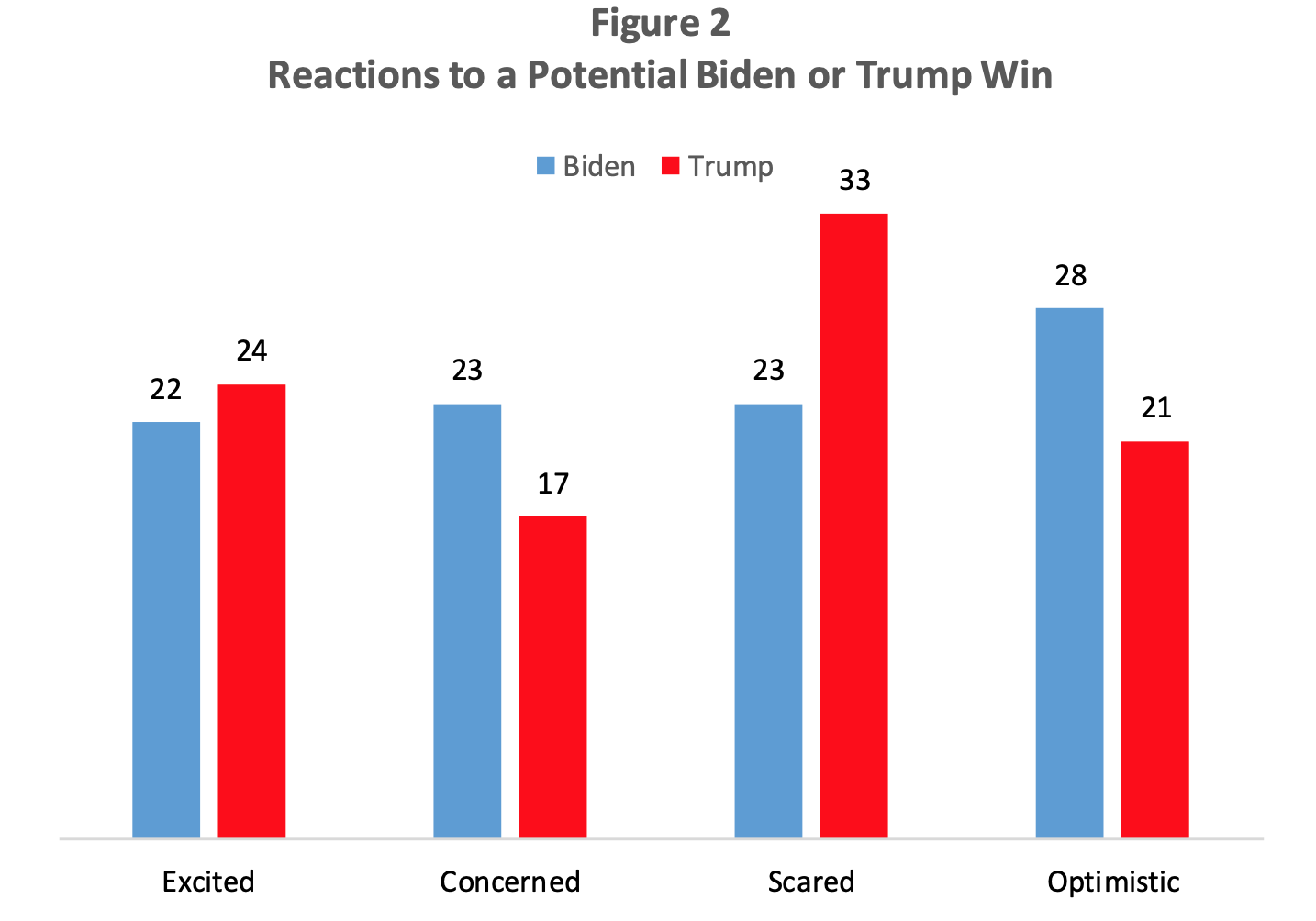

Anticipated reactions: Hotly contested elections often leave one side feeling optimistic and the other feeling disappointed. Although the exit poll was conducted before voters knew who won, emotions were on clear display. The survey asked voters to identify the word that best summarizes their reaction to a potential win: excited, optimistic, concerned, or scared if Biden won. They then asked the same question about a Trump victory. Optimistic was the word most associated with a Biden win; scared was used most frequently to describe a Trump victory (see Figure 2).

Importantly, of those who expressed excitement or optimism about a potential Biden win, more than 90 percent voted for him. Trump drew the support of a similar proportion who were excited about a second term. The opposite is true for those who said they were concerned or scared. Biden won the votes of 78 percent of voters concerned about a Trump win and 96 percent of those scared by the prospect. Meanwhile, 92 percent of voters who were concerned about Biden and 93 percent who were scared by him voted for Trump. Because voters were more optimistic about Biden and more scared by Trump, the net advantage went to Biden.

—Jennifer Lawless, Commonwealth Professor of Politics and chair of the Politics department, University of Virginia; Miller Center senior fellow

—Paul Freedman, associate professor, Politics department, University of Virginia

Superficially, many in Asia welcomed President Donald Trump’s tough talk about China, praising his administration’s emphasis on “strategic competition” with Beijing. But his policies—particularly on trade and investment—are widely viewed as having undercut that goal. President-elect Joe Biden now has an opportunity to set the stage for more systematic, institutionalized, and effective competition with Beijing.

Trump’s Approach: Long on Attitude, Short on Strategy

Despite Trump’s fighting words about competing with China, many Asian governments, broadly speaking, have viewed his administration’s policies as inconsistent with this goal. Some leaders, notably in Southeast Asia, abhor Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s stark “us or them” framing, preferring to view their region in balance-of-power rather than ideological terms. And America’s closest allies, especially Japan and Australia, loathe Trump’s trade policies, not least his decision to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal.

In the wake of American withdrawal, eleven countries completed the TPP without the United States—in effect, setting the region’s trade and investment standards without its largest economy and traditional standard setter. In a region whose business is business, that gap between American rhetoric and action has been a source of consternation to governments that view full-spectrum U.S. engagement as an essential balance to the rise of Chinese power.

Just take Southeast Asia, which the Trump administration viewed as ground zero of strategic competition with Beijing. In the last four weeks alone, Washington has picked trade fights with two strategically pivotal countries—Vietnam, which it is investigating for alleged currency manipulation, and Thailand, whose duty-free trade privileges the Trump administration has just revoked.

—Evan Feigenbaum, senior fellow, Miller Center

Miller Center senior fellow Chris Lu, who ran the Obama administration's transition in 2008–9 has been in demand for commentary on this year's transition-in-waiting. Here he talks to MSNBC about the national security risks

REPUBLICAN RELUCTANCE

GOP leaders hesitate to congratulate the president-elect. Biden looks forward. UVA experts assess.

November 10, 2020

Today's posts

Exit Poll Nuggets™: What mattered most • Jennifer Lawless and Paul Freedman

Jill Biden keeps working • Jennifer Lawless

Former DHS secretaries: Begin the transition • Tom Ridge, Michael Chertoff, Janet Napolitano, Jeh Johnson

The personal side of the election • Naomi Cahn

Undoing Trump will push Biden to executive action • Rachel Augustine Potter

Welcome back to Exit Poll Nuggets™.

Today, we highlight several fun facts that the exit poll results reveal, including which issues mattered most in this election. As noted last week, in the immediate aftermath of a national election, exit polls offer the best glimpse of what the electorate looked like—who voted for whom and what seemed to drive their choices. In 2020, the exit polls combined interviews with a representative sample of thousands of voters (leaving polling places in a representative sample of precincts across the nation) and telephone interviews with a representative sample of people who voted early or by mail.

In all, the national exit poll includes interviews with 15,590 voters. It is important to note that these data will be updated, so the numbers below should be considered preliminary, reflecting the exit polls reported as of Wednesday, November 4.

First time voters: Thirteen percent of voters reported casting a ballot for the first time in 2020. Among these first-time voters, Biden outperformed Trump two to one (66 vs. 32 percent).

Swing voters: The overwhelming majority of Democrats and Republicans vote for their party’s presidential candidate every four years. But Biden fared better than Trump among the small segment of the electorate who swing back and forth. Biden won 8 percent of those who reported having voted for Trump in 2016; Trump won 4 percent of self-reported 2016 Hillary Clinton voters.

Moderates: Biden and Trump performed well with the endpoints of the ideological spectrum. That is, Biden won the 24 percent of liberal voters by a substantial margin (89 vs. 10 percent for Trump), and Trump won the 37 percent of conservative voters by a similar margin (84 vs. 14 percent for Biden). When it comes to the 40 percent of voters who identify as moderates—the slice of the electorate who tend to decide elections—Biden had a significant edge: 64 percent of moderates chose Biden, whereas only 33 percent favored Trump. This is a sizable drop from the 40 percent of moderates who voted for Trump in 2016.

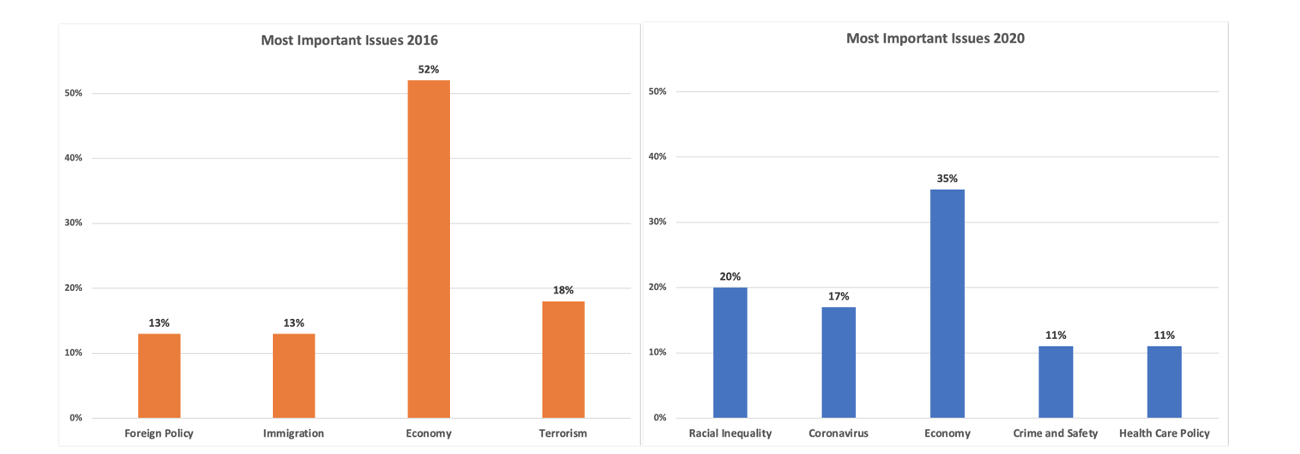

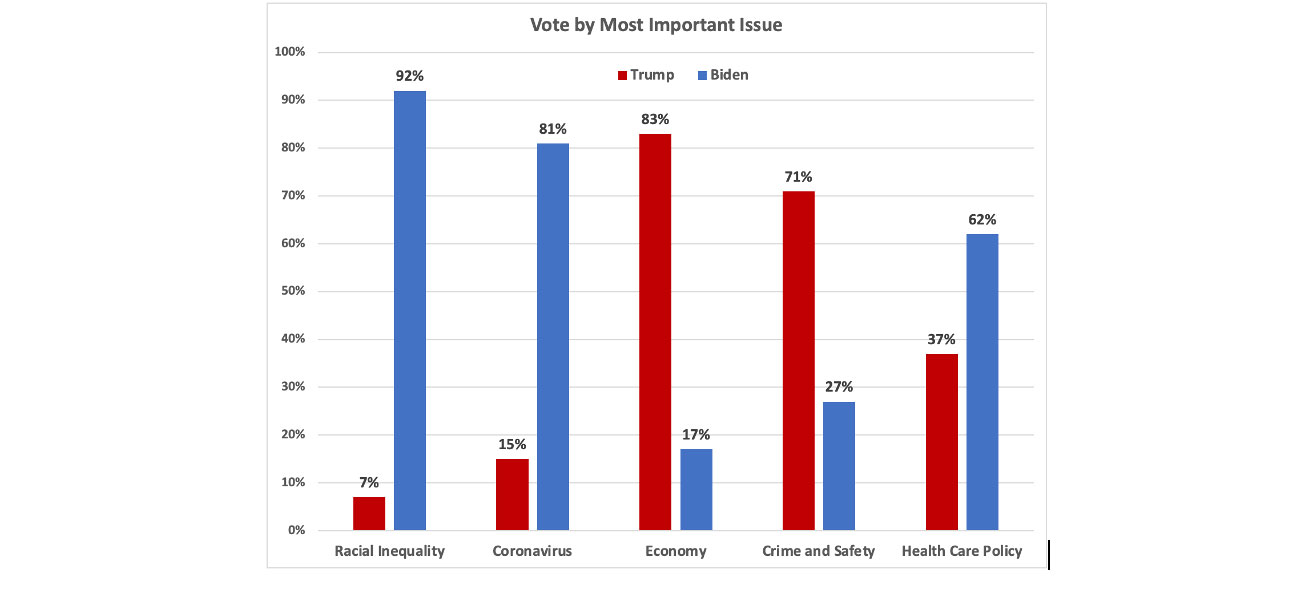

Most important issues, 2016 vs. 2020: In both 2016 and 2020, the exit poll presented voters with a list of issues, asking them to choose the one that “mattered most in deciding how you voted for president” (see Figure 1).

In 2016, voters were presented with a list of four issues (and from the perspective of 2020, they seem so distant, almost quaint). In 2020, they were given five issues. Notice that only the economy appears on both lists. And even it took a hit in terms of most important status (52 percent of voters prioritized it in 2016, compared to 35 percent in 2020). Competing for voters’ priorities in 2020 was the somewhat vaguely labeled “racial inequality” (20 percent), followed by the coronavirus (17 percent), “crime and safety” (11 percent), and health care policy (11 percent).

Vote Choice, by Most Important Issue. The exit polls make it clear that Democrats and Republicans not only voted for different candidates, but they based their decision on different issues (see Figure 2). The lion’s share of voters who prioritized the economy and “crime and safety” voted for Trump, while voters who cared most about racial inequality, the pandemic, and health care voted for Biden (see Figure 1). This is hardly surprising, given the focus of each candidate’s campaign, but it is striking to observe the extent to which Biden and Trump voters seemingly viewed the election in terms of a completely different set of issues.

Black Lives Matter: The majority (57 percent) of voters have a favorable view of Black Lives Matter, and Biden won the support of 80 percent of these voters. Trump did just as well as among the 30 percent of voters with an unfavorable view of Black Lives Matter, receiving 85 percent of their votes.

Masks: Two-thirds (67 percent) of the electorate believe that wearing a mask in public is “more of a public health responsibility,” whereas 30 percent say it is “more of a personal choice.” Although Biden won 64 percent of voters who view masks as a public health responsibility, Trump did better among those who view it as a personal choice, receiving 72 percent of their votes. Given the strong majority in support of masks, this was clearly an issue that helped Biden in the aggregate.

Other issues: As we’d expect, Biden outperformed Trump among voters who think that climate change is a serious problem (69 percent voted for Biden, compared to 29 percent for Trump); that abortion should be legal (74 percent cast votes for Biden, compared to 21% for Trump); and that Obamacare should remain in place (80 percent went for Biden, and 18 percent for Trump). It’s not only the margin that matters, though. In each case, a greater share of the electorate shared Biden’s position. More specifically, two-thirds of voters considered climate change a serious problem, and a small majority (51 percent) thought abortion should be legal and Obamacare should be preserved. Even though these weren’t the most important issues in 2020, they likely contribute to Biden’s victory.

We’ll be back tomorrow with another Exit Poll Nugget™, which will focus on candidate qualities and traits.

—Jennifer Lawless, Commonwealth Professor of Politics and chair of the Politics department, University of Virginia; Miller Center senior fellow

—Paul Freedman, associate professor, Politics department, University of Virginia

In the Huffington Post, Miller Center senior fellow and UVA Department of Politics chair Jennifer Lawless discusses Jill Biden's commitment to continuing her teaching job—just as she did when her husband was vice president—once the Bidens move into the White House.

"It sends a very strong message to women: No matter how accomplished, powerful, or important your husband, you don’t have to abandon your own career or play second fiddle," Lawless says. And, she adds, "It demonstrates that education will be front and center in a Biden administration, which is a significant departure from the last four years."

Four former Department of Homeland Security secretaries, two Republicans and two Democrats, are calling for President Trump to begin the transition process even as he pursues legal challenges. Tom Ridge and Michael Chertoff, who served in the Bush 43 administration, joined Janet Napolitano and Jeh Johnson, who worked for President Obama, to issue the open letter. The four are partners in the bipartisan, nonprofit Citizens for a Strong Democracy, founded in order to strengthen public confidence in the election systems and the results of the vote. Citizens for a Strong Democracy is a partner with the UVA Institute of Democracy in providing expert UVA commentary on the 2020 election.

Here is the letter in its entirety:

Voting in the 2020 presidential election is over and the American people have made their voices heard. By all credible accounts, state election officials have been diligent in conducting a fair, legal, and accurate count—county by county, state by state. President Trump is assured the benefit of a fair process and the right to file legal challenges and request recounts in certain states, but his legal claims cannot and must not prevent the transition process from beginning. The Presidential Transition Act requires a transition to run concurrently with any election challenges and is intended to ensure the incoming administration is prepared to handle any challenge on Day 1.

A peaceful transfer of power was defined as essential to national security by the 9/11 Commission. It was critical following the 2008 election, when the country was confronted with active terror threats during the transition and what was then the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. It was essential in 2016 when America was working to defeat ISIS. And it is essential now.

As four former Secretaries of Homeland Security, we have actively participated in presidential transitions. One of us, Secretary Chertoff, who served under President George W. Bush, oversaw the transition of the Department of Homeland Security to another of us, Secretary Napolitano, who served under President Barack Obama. And, Secretary Johnson oversaw the DHS transition from the Obama administration to the Trump administration.

Leaders must protect our historic democratic processes. We will use every resource at our disposal to support our republic’s cherished, peaceful and orderly transition of power between administrations.

Our country is in the middle of twin crises: a global pandemic and a severe economic downturn. The pandemic will make any transition more complicated. At this period of heightened risk for our nation, we do not have a single day to spare to begin the transition. For the good of the nation, we must start now.

The latest from Citizens for a Strong Democracy

What does the election tell us about our personal lives? It turns out that politics matters not just to our voting patterns but to whom we date, whom we marry, and where we live.

OKCupid, a dating site, reports that more than three-quarters of its respondents claimed that “how their date leans politically is very important.” It also found a gender gap far larger than the 2020 exit polls, with 73 percent of women leaning Democratic, compared to 57 percent of men (the national statistics were 57/45 percent). It turns out that women were also more likely than men to say they preferred dating someone who had the same political views.

When those dating relationships turn into marriage, people are more likely to choose partners who share the same political affiliation. As a recent study found, 79 percent of marriages are between people who identify with the same party. Only 4 percent are between Democrats and Republicans, and the remaining 17 percent are between independents and those who identify with one of the two major parties.

And then there’s the question of how you’d feel if your child married someone of the opposite political party. There, more Democrats—45 percent—would be displeased compared to 35 percent of Republicans. In a sign of just how politically polarized we have become, only 4 percent of Republicans or Democrats would have been unhappy with a political mixed marriage back in 1960.

Our residential patterns also increasingly reflect our politics. Since 1976, when only 26 percent of voters lived in a place where one party won by an overwhelming majority in a presidential election, that number has steadily increased. While Biden won urban areas with 60 percent of voters, Trump won rural areas with 57 percent. Politics may affect not only where people move, but also their political preferences once they get there. People are much less likely to interact with others from another political party at local civic gatherings than at work.

Politics—and party affiliation—profoundly influence our personal choices.

—Naomi Cahn, director of the Family Law Center, UVA School of Law

After a hard fought (and still contested) victory, president-elect Joe Biden now faces the daunting task of governing in a highly polarized environment. While candidate Biden advanced a number of ambitious policy initiatives, much of the work ahead for the new administration will focus not on the achievement of new policy proposals, but instead on the unwinding of policies enacted by the Trump administration. And because so much of that unwinding is likely to occur through executive action, Biden’s first year in office is likely to be heavily executive-oriented.

Executive action underpinned many of Trump’s highest profile achievements, including actions to limit immigration, curb the number of new regulations, and ban the service of transgender people in the military. With the stroke of a pen, President Biden will likely issue orders pulling back Trump’s most controversial measures immediately after assuming office in January. He is also likely to use his executive authority to reengage the United States in the international community, by rejoining the Paris climate accords and the World Health Organization.

Other Trump actions will take much longer for the new president to roll back. Much of this administration’s deregulatory campaign has been carried out through a cumbersome and time-consuming bureaucratic process, known as “notice and comment” rulemaking. Since reversing course on these regulatory actions involves following the same process, this means the new administration could be tied up for many months—if not years—just in rolling back Trump’s deregulatory program. (However, the Biden administration could catch a major break if Democrats are able to eke out a majority in the Senate, as a Democratic Congress could legislatively overturn some of the Trump administration’s last-minute deregulatory efforts using an obscure law known as the Congressional Review Act.)

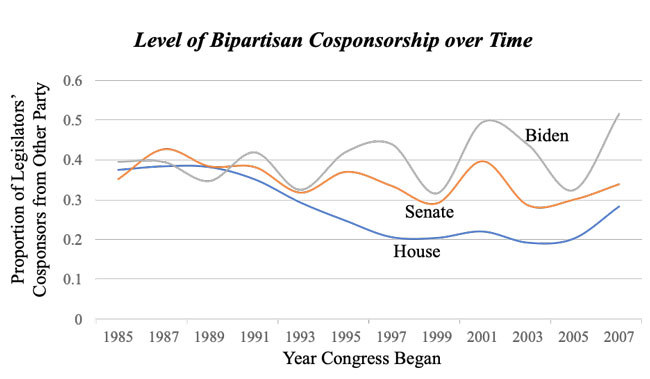

Nevertheless, the focus on the “undoing” of Trump’s legacy suggests that the early months of the Biden administration are likely to appear heavy on unilateral presidential action—even before the new president has had a chance to advance his own policy priorities. Once Biden has the bandwidth to engage his own policy agenda, this perception may intensify, particularly if the Senate stays in Republican hands and Republican senators refuse to work with the White House.

Unilateral action has become a centerpiece of the modern presidency, and the Biden administration is poised to continue this trend.

—Rachel Augustine Potter, assistant professor, UVA Department of Politics

BIDEN PRESSES AHEAD

With myriad problems facing the nation, President Trump refuses to concede defeat. UVA Institute of Democracy scholars react.

November 9, 2020

Today's posts

A legal assessment • Michael Gilbert

Harris's rise, Biden's performance • Barbara Perry

How transitions usually happen, how this will be different • Chris Lu

President-elect Biden's Covid-19 task force • Margaret Riley

Exit poll nuggets™: The LGBTQ vote • Jennifer Lawless and Paul Freedman

The next chapter of executive-centered partisanship • Sidney Milkis

The complex politics of a Covid-19 vaccine • Guian McKee

Is Donald Trump the next Grover Cleveland? • Barbara Perry

UVA law professor Michael Gilbert joins CNBC to assess the Trump campaign's attempts to challenge the results of the 2020 election through legal action.

Barbara Perry is the Miller Center's director of Presidential Studies and an expert on both the presidency and the Supreme Court. Several media outlets took advantage of her expertise to add critical historical perspective to the latest news.

She joined PBS NewsHour to reflect on Kamala Harris's historic ascension to the vice presidency:

After Joe Biden's victory speech, Perry appeared on NewsNation Now to assess his performance:

Miller Center senior fellow Chris Lu, who ran the Obama administration's transition in 2008–9, is the ideal candidate to explain how President Trump's behavior in the aftermath of the 2020 election will affect the Biden team and the nation.

He joined several media outlets to discuss, sitting down with NPR's Ari Shapiro:

Lu also joined Fox 5 DC:

And Lu appeared on CBS news:

As promised during his victory speech on Saturday night, president-elect Joe Biden announced on Monday morning the formation of a task force to combat Covid-19. While most of the task force members are not exactly household names, they are all exceptionally well-respected scientists, physicians, and public health experts. Many have significant government experience.

The choice of the task force’s three chairs is strategic. Former surgeon-general Vivek Murthy understands the federal apparatus and the CDC, and may prove crucial in rebuilding trust in that beleaguered agency. David Kessler is former commissioner of the FDA and also has significant public health experience. The least well-known, Marcella Nunez-Smith, is a physician whose research agenda focuses on health disparities—a crucial recognition that the virus has not affected everyone in the same way.

The task force has no actual power, which may end up being of no consequence, or possibly even an advantage. While the limits of federal power in compelling health behaviors are subject to dispute, the real power of the federal government in managing Covid-19 is likely to be advisory rather than compulsory.

For that it needs trust, not mandates. Indeed, issuing mandates may even erode trust. By starting with a position of expertise that spans most of the essential domains, the task force will be able to provide states with coherent evidence-based data and guidelines—something that has been lacking since the beginning of the crisis.

Pfizer’s announcement on Monday morning of preliminary results indicating that its vaccine is 90 percent effective was also serendipitous for the task force. The prospect of a vaccine that may exceed even optimistic hopes of efficacy, coming within months, provides some parameters for a timeline for the task force. It can get quickly to the essential work of planning equitable distribution, as well as monitoring other promising treatments, tests, and vaccines.

This also means that any restrictive behavioral guidelines issued by the task force will be temporary. It is much easier for people to forgo activities or to wear masks and observe tighter social-distancing rules if there is a clearer end in sight.

—Margaret Riley, professor of Law, UVA School of Law; professor of Public Health Sciences, UVA School of Medicine

Welcome back to Exit Poll Nuggets™.

Today, we take up a reader-submitted question, focusing on LGBTQ voters and how their votes in 2020 compare to previous years. As noted last week, in the immediate aftermath of a national election, exit polls offer the best glimpse of what the electorate looked like—who voted for whom and what seemed to drive their choices.

In 2020, the exit polls combined interviews with a representative sample of thousands of voters (leaving polling places in precincts across the nation) and telephone interviews with a representative sample of people who voted early or by mail. In all, the national exit poll includes interviews with 15,590 voters. It is important to note that these data will be updated, so the numbers below should be considered preliminary, reflecting the exit polls reported as of Wednesday, November 4.

First, some important caveats: It is notoriously challenging to survey small groups of voters, including members of religious or other demographic minorities. It is arguably even more challenging when it comes to LGBTQ identity, for which estimates of the total population are just that: estimates.

According to 2017 Gallup data, 4.5 percent of Americans answered “yes” when asked, “Do you, personally, identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender?” This is an increase from 4.1 percent in 2016 and 3.5 percent in 2012. (Note: Although we’re using the slightly more inclusive LGBTQ term, what is actually being measured, both by Gallup and by the exit poll, is LGBT identification.)

These changes most likely reflect differential willingness to identify as LGBTQ. For example, in 2017 Gallup found that 2.4 percent of Baby Boomers and a full 8.2 percent of Millennials identified as LGBT. And these generational differences have widened over time.

Finally, it is important to remember that, as with any survey, the margin of sampling error for any subgroup is going to be larger than for the full sample; the smaller the subgroup, the more uncertainty around our estimates.

With all of that in mind, the 2020 exit poll found that 7 percent of the electorate identified as “gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender,” up from 5 percent in 2016. This suggests that in both elections, the LGBTQ community is over-represented in the exit polls, but the upward trend is likely consistent with those in the actual population.

The vote choice of LGBTQ voters in 2020 was, put simply, a surprise to many: More than a quarter of LGBTQ voters—28 percent—cast a ballot for Donald Trump, while 61 percent voted for Joe Biden. In 2016, by contrast, 78 percent of LGBTQ voters supported Democrat Hillary Clinton, similar to the 76 percent who voted for Barack Obama in 2012.

Why the change? It’s hard to know for sure, but we reiterate our caveats about survey uncertainty when it comes to small groups. And more generally, these findings are a reminder that, as with Black and Latinx voters, no subgroup is monolithic in its political views or voting behavior. LGBTQ voters live in every state and reflect a diversity of backgrounds, experiences, and opinions.

At the end of the (election) day, though, it’s important to keep in mind that, at 61 percent, LGBTQ Americans voted about as Democratic as 18–29-year-old voters (62 percent Biden) and more Democratic than every other age group. They voted more Democratic than men (48 percent) and women (56 percent), and people who live in the suburbs (51 percent) or in cities (60 percent). And the 33-point margin by which Biden won LGBTQ voters is substantial—bigger than the gaps for gender, income, marriage, and many other divides. LGBTQ voters are, ultimately, Democratic voters.

Check back tomorrow for more on what the exit polls tell us about issues, candidate traits, and the political climate in 2020.

—Jennifer Lawless, Commonwealth Professor of Politics and chair of the Politics department, University of Virginia; Miller Center senior fellow

—Paul Freedman, associate professor, Politics department, University of Virginia

The likely continuation of divided government and legislative stalemate has dampened the enthusiasm of the Democratic Party’s base in the aftermath of Joe Biden’s stirring victory. However, recent history reveals that presidents can accomplish a great deal on their own. Since the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt, but especially since the cataclysmic 1960s, Democrats and Republicans have depended on presidents to pronounce party doctrines, mobilized base supporters, raise campaign funds, and advance party programs. This phenomenon sits at the crossroads of two related developments: the decline of party organizations and the expansion of executive power.

The confluence of these two trends took on a more antinomian form with the culture wars of the 1960s, reckonings over American identity that reverberate through our own time. These struggles over race, religion, and immigration have fueled ideological polarization and a legislative stalemate in Congress, which has made parties even more dependent on presidents to advance their objectives. As a consequence, presidents of both parties have sought to achieve their policy objectives with administrative powers rather than navigate a complex system of separated powers to pass legislation.

This development reached a culmination with Obama and Trump. Both administrations placed a premium on the White House office (the West Wing) and other agencies in the executive office of the president, many of which do not require senate confirmation. Both Obama and Trump anointed policy czars, who were ensconced in the White House and charged with formulating programs and developing administrative strategies to bring them to fruition. For example, immigration policy in the Obama administration was directed by Domestic Policy Advisor Cecilia Munoz, who oversaw the implementation of controversial decisions like establishing deportation relief and work authorizations for “Dreamers” (DACA).

Both Obama and Trump anointed policy czars, who were ensconced in the White House and charged with formulating programs and developing administrative strategies to bring them to fruition.

Similarly, Trump’s draconian immigration policy has been directed from the West Wing by Stephen Miller, who not only has been at the vanguard of rescinding initiatives like DACA but also has been using the cover of the pandemic to pursue highly suspect tactics, like the deportation of children who travel to the United States without a parent or guardian, while obviating the substantial due-process requirements designed to ensure that deportation would not place them in harm’s way.

Therefore, although much of the media’s attention on the runup to a new presidential administration is on Cabinet appointments, we should pay close attention to president-elect Biden’s choices for the executive office. As demonstrated by the selection of three prominent physicians to head his coronavirus task force, these appointments will come more quickly and will give a good indication of the Biden’s administration’s political and policy ambitions.

The members the new president’s personal team will be formulating a flurry of executive orders in matters pertaining to the war against the pandemic, health care, immigration, climate change, and police reform that will change the trajectory of the Trump administration’s programs. Very quickly, we can expect the Biden administration to restore DACA and the rights of unaccompanied child refugees; buttress the Affordable Care Act, most notably the elimination of work requirements that the Trump administration attached to Medicaid Expansion; rejoin the Paris Accords on climate change; and restore the Obama administration’s robust oversight of police departments found to have violated the rights of citizens in their jurisdictions.

The expectation of Democrats and Republicans that presidents should cut the Gordian knot of harsh partisanship is understandable given the high stakes of domestic and foreign policies now in play. But the concentration of power in the White House—as part of a presidency-centered democracy—both weakens the constitutional system of checks and balances and places unreasonable and dangerous expectations on presidents.

Dueling administrative swords also makes a Chimera of the rule of law, the foundation of a republic. President-elect Biden—a self-proclaimed institutionalist—intends to restore unity to the country and end the legislative stalemate. But this will be a herculean task in a political culture that encourages churning conflict and mounts pressure to advance partisan objectives in a sharply divided nation.

—Sidney Milkis, White Burkett Miller Professor of Governance and Foreign Affairs, Miller Center

This morning, the world received the welcome news that preliminary results from a Phase 3 trial show that the Covid-19 vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech is 90 percent effective, with no serious safety concerns. While a long road remains in terms of final trial stages, emergency approval, manufacturing, and distribution, the results are an immense relief and better than many people anticipated.

At long last, there is more hope that the pandemic can be brought under control over the next 6 to 18 months. Hundreds of other vaccines are under development.

How does this stirring development relate to the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election? While it will not shape the bitter final struggles over vote counts and legal challenges, it relates directly to another facet of the post-election period: the initial shaping of the president’s historical legacy.

Donald Trump is very likely to rank among the worst American presidents. His accomplishments are of a nature that please only his dedicated partisans, and his failures of leadership and management are too numerous and well-known to warrant full discussion here. Chief among them, though, is his administration’s indifferent and disastrous response to the pandemic, and especially its tragic failure to support basic public health interventions such as mask-wearing and social distancing.

But there was one area where the administration did respond vigorously: Operation Warp Speed, the effort to develop a vaccine in record time. And now we have—it seems—such a vaccine.

How will this shape historians’ assessment of the Trump administration’s record? As with so much of presidential history, the answer is more complicated than a first impression would suggest.

Most notably, Pfizer and BioNTech did not use Operation Warp Speed funding in the development of their vaccine. As Kathrin Jansen, Pfizer senior vice president and head of vaccine research development, told the New York Times, “We were never part of the Warp Speed. We have never taken any money from the U.S. government, or from anyone.”

On pure scientific grounds, then, the first vaccine came about without the help of the administration.

Not only that, the vaccine was actually developed by scientists at BioNTech—a German company. Lacking the capacity to conduct a trial or manufacturing at scale, BioNTech came to Pfizer for help.

On pure scientific grounds the first vaccine came about without the help of the administration.

In part, the two companies chose not to participate in Operation Warp Speed because they wanted to join COVAX, the broader international vaccine effort funded through the World Health Organization and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). President Trump prevented the United States from joining the COVAX project, preferring to prioritize an exclusive vaccine for Americans.

The resulting (apparent) success is thus an example of international cooperation (and decidedly not of “America First”). This is exactly the sort of partnership across borders that Trump has consistently derided. More broadly, the failure of the United States to lead in coordinating across governments, private companies, public health institutions, and non-governmental organizations has worsened the global pandemic and cost a still unknown number of lives.

Yet a story of the Pfizer-BioNTech effort as a fully independent endeavor is also too simple. The administration did move aggressively, and at some risk, to sign an advance purchase agreement with Pfizer. Manufacturing and distribution of the vaccine in the United States will also inevitably rely on the plans and structures that Warp Speed has developed.

This is exactly the sort of partnership across borders that Trump has consistently derided.

Further, other vaccines may still play a part in containing the pandemic. One of the leading candidates was developed by Moderna, which relies on mRNA in a manner similar to the Pfizer-BioNTech version. A much smaller company, Moderna has participated in Warp Speed and relied on its funding for support.

A final layer of complexity is added by the matter of politics, particularly as the United States moves into a difficult and contentious presidential transition period. The vaccine development effort has of course taken place in the hothouse environment of the presidential campaign. Optimistic statements by Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla during the summer and early fall raised concerns that the vaccine testing and approval process would be politicized, particularly after Trump seized on the comments as evidence that a vaccine would be ready before the election.

The backlash led Pfizer to form an alliance with other pharmaceutical companies to maintain scientific standards and resist political pressure during the trial process. The FDA also tightened its own standards for an emergency-use authorization. Yet the damage had been done, as public doubts about a vaccine’s safety heightened due to fears that it was a political tool. Gaining public trust in the vaccine will be an ongoing challenge for the Biden administration and the public-health community at large.

Any historical assessment of Trump’s record on the vaccine effort will need to take account of the consequences of his statements on the public’s response to the availability of a vaccine.

Trump-led attempts to disrupt the transition process could further hinder development of that trust, not to mention the implementation of distribution plans (although fortunately much of that work can take place beyond the reach of the president’s capacity to block funding for the transition to the next administration).

It is important to close by noting that much remains unknown about the details of Operation Warp Speed’s work, and that its ultimate success will depend as much on the effective distribution of the vaccine as on its actual development. What is clear, however, is that the Trump administration’s record and legacy will be intertwined with this work in complex ways that will give both his supporters and his critics ample material for historical debate and analysis.

We rarely know as much about a presidency as we think we do while events are unfolding.

—Guian McKee, associate professor in Presidential Studies, Miller Center

Is Donald Trump the next Grover Cleveland? They certainly have the same body type—rotund. Both have a history of womanizing: Cleveland fathered a child out of wedlock; Trump’s three marriages and porn-star liaisons are infamous. Each president is known for characteristic hair styles—Cleveland’s walrus mustache, popular in the late 19th century, and Trump’s combover, a last resort for balding men in any era. Both suffered medical emergencies during their presidencies (Cleveland’s cancer surgery; Trump’s COVID diagnosis) and tried to keep details from the public. Each lost reelection on their first try for a second term.

Here is where Trump hopes he can follow in Cleveland’s footsteps. Having lost in his bid for reelection to Benjamin Harrison in the controversial race of 1888, despite winning the popular vote, the 22nd president moved back to New York. As Mrs. Cleveland departed the White House, however, she asked the staff to take good care of the furnishings because she and her husband would return in four years. And they did!

Cleveland thwarted Harrison’s reelection effort in 1892, thus becoming the only U.S. president to serve two nonconsecutive terms. A Newsweek reporter has already speculated that Trump aspires to run for the White House again in 2024. But to become both the 45th and 47th president of the United States, he will not only have to avoid imprisonment, should New York state prosecutors succeed in convicting him of tax evasion and/or criminal acts related to the Trump Foundation, but he will have to ensure that the next four years cement his leadership of the Republican Party.

Are GOP senators—like Texas’s Ted Cruz and Arkansas’s Tom Cotton, who support the president’s claims that the 2020 election was stolen by the Biden campaign—gunning for the vice-presidential spot on another Trump ticket four years hence or laying the groundwork for their race to the White House should Trump fail at becoming the country’s next Grover Cleveland?

—Barbara Perry, Gerald L. Baliles Professor, director of Presidential Studies, Miller Center

LIVE TAPING: “AFTERMATH: DEMOCRACY IN THE WAKE OF 2020”

Hosts Will Hitchcock and Siva Vaidhyanathan of the UVA “Democracy in Danger” podcast will explore the ramifications of the presidential election on November 12 at 2:00 ET

October 29, 2020

Join us at 2:00 ET on November 12 for a live recording of “Democracy in Danger,” a new podcast from UVA's Deliberative Media Lab. On this episode, special guests Carol Anderson, Melody Barnes, Leah Wright-Rigueur, and Ian Solomon discuss the challenges facing democracy in the wake of 2020. After a historic year marked by a global pandemic, economic catastrophe, educational upheaval, the struggle for racial equity, and a chaotic national election, what is America's path forward?

FROM ELECTION TO TRANSITION

The transition from the Trump to the Biden administration promises to be unlike any other in history. Here's what UVA Institute of Democracy scholars have to say.

November 8, 2020

Today's posts

What the Biden team faces in transition • Chris Lu

This does not have to be a political crisis • William Antholis

‘This is about the peaceful transfer of power’ • Melody Barnes

Chris Lu, a Miller Center senior fellow, ran the Obama administration transition in 2008–9. He talks with NPR about what Joe Biden's team faces this time around.

It is not that close. This does not have to be a political crisis.

We have just completed a narrow, hard fought election. Given the ongoing economic crisis and pandemic, the country should begin the peaceful transfer of power.

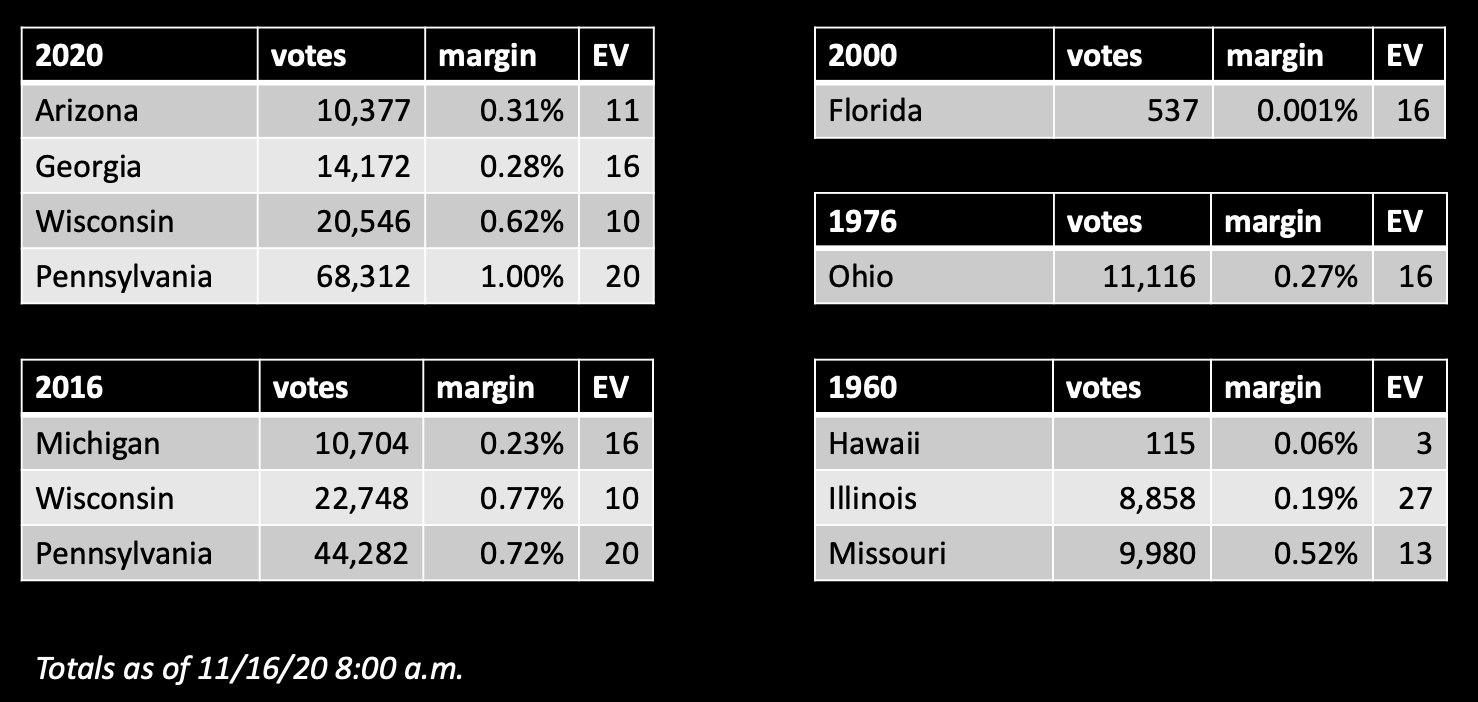

President Trump has indicated he will pursue legal challenges to the election results. But the chances of a recount flipping tens of thousands of votes across multiple states in his favor are outside anything we have seen in American history.

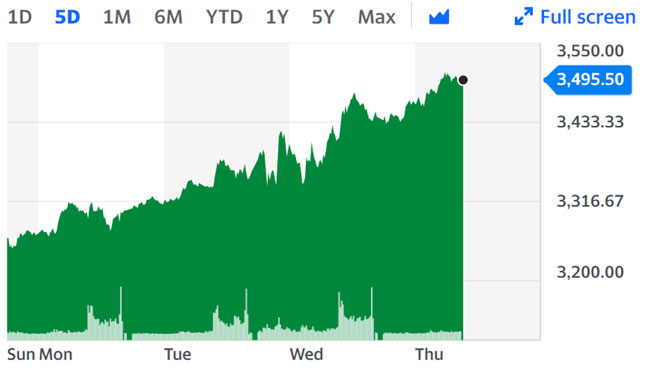

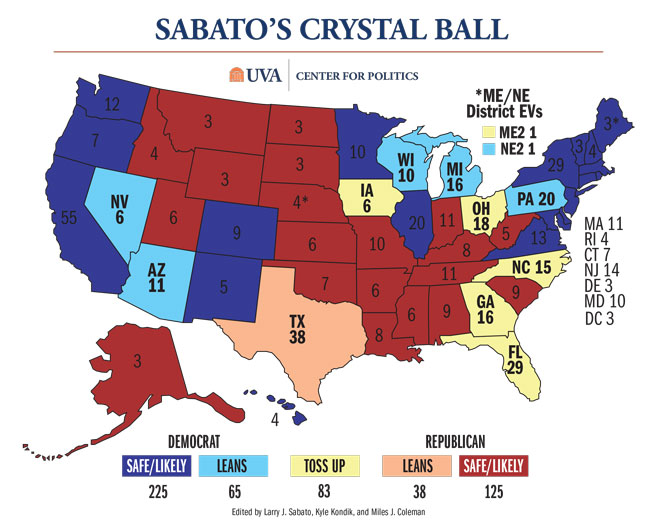

When compared with other close elections, this one is actually quite a comfortable victory for President-elect Biden. The Biden-Harris ticket has won or is significantly ahead in states worth 306 electoral votes.

For Trump to win, he must flip at least three of the four narrowest margins of defeat, where he either must persuade courts to disqualify tens of thousands of ballots or have recounts overturn results in three of the four closest “tipping point” states that put Biden over the 270 threshold.