John F. Kennedy: Foreign Affairs

Once in office, it was clear that Kennedy would likely face several international challenges that could come from any number of directions. Recurring flare-ups in Berlin, periodic crises with Communist China, and an increasingly vexing situation in Southeast Asia, all threatened to erupt.

The Bay of Pigs

It was Cuba, however, that was the site of an immediate crisis, largely of the administration's own making. Kennedy had only been in office two months when he ordered the implementation of a covert CIA plan inherited from the Eisenhower administration—which he altered dramatically—to topple Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Assured by military advisers and the CIA that its prospects for success were good, Kennedy gave the green light. In the early hours of April 17, 1961, approximately 1,500 anti-Castro Cuban refugees landed at Bahia de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) on Cuba's southern coast. A series of crucial assumptions built into the plan proved false, and Castro's forces quickly overwhelmed the refugee force. Moreover, the Kennedy administration's cover story collapsed immediately. It soon became clear that despite the president's denial of US involvement in the attempted coup, Washington was indeed behind it. The misadventure cost Kennedy dearly. Yet his administration continued to press for Castro’s ouster, launching the CIA-backed Operation Mongoose in November 1961 to harass and destabilize the Cuban regime.

Vienna and Berlin

Still recovering from this humiliating political defeat, Kennedy met with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna in June 1961. Khrushchev renewed his threat to “solve” the long-running Berlin problem unilaterally, an announcement that in turn forced Kennedy to renew his pledge to respond to such a move with every means at his disposal, including nuclear weapons. In a dramatic move two months later, in mid-August 1961, the Soviets and East Germans constructed a wall separating East and West Berlin, providing the Cold War with its most tangible incarnation of the Iron Curtain.

Missiles in Cuba

By the fall of 1962, Cuba again took center-stage in the Cold War. In an effort to protect the Castro government, compete with China for the hearts of revolutionaries worldwide, and neutralize the massive American advantage in nuclear weapons—particularly as part of any new Berlin gambit—Khrushchev ordered a secret deployment of long-range nuclear missiles to Cuba along with a force of 42,000 Soviet troops and other associated conventional and atomic weaponry. For months, despite close American scrutiny, the Soviets managed to keep hidden the full extent of the buildup. But in mid-October, US aerial reconnaissance detected the deployment of Soviet ballistic nuclear missiles in Cuba which could reach most of the continental United States within a matter of minutes.

By the fall of 1962, Cuba again took center-stage in the Cold War. In an effort to protect the Castro government, compete with China for the hearts of revolutionaries worldwide, and neutralize the massive American advantage in nuclear weapons—particularly as part of any new Berlin gambit—Khrushchev ordered a secret deployment of long-range nuclear missiles to Cuba along with a force of 42,000 Soviet troops and other associated conventional and atomic weaponry. For months, despite close American scrutiny, the Soviets managed to keep hidden the full extent of the buildup. But in mid-October, US aerial reconnaissance detected the deployment of Soviet ballistic nuclear missiles in Cuba which could reach most of the continental United States within a matter of minutes.

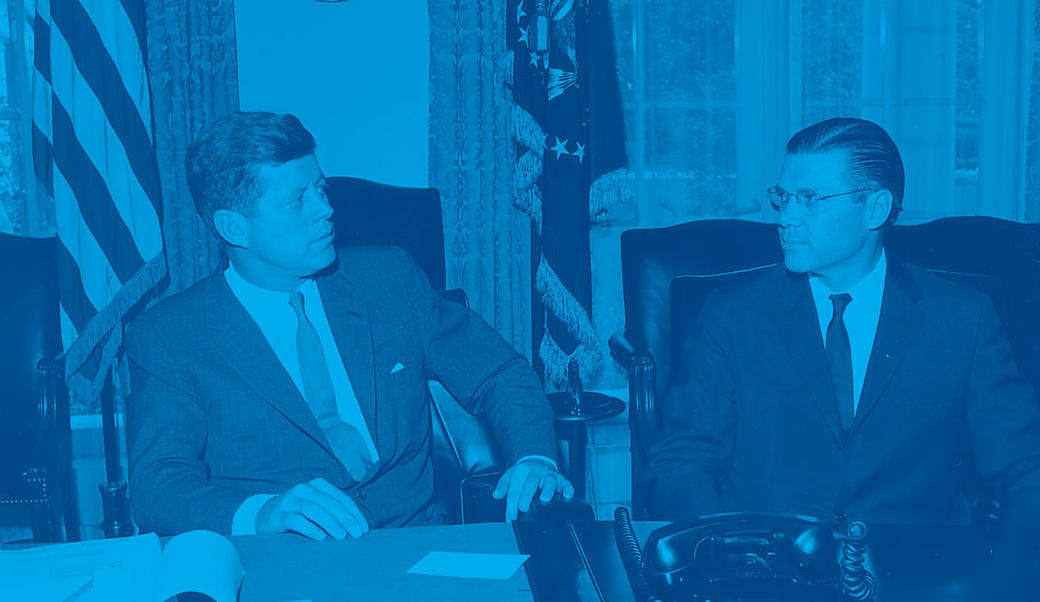

Kennedy consulted with his top advisers over a period of several days. These meetings, conducted by the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or ExComm, took place in utmost secrecy in order to maximize the range of available responses. Among the options considered were air strikes on the missile bases, a full-scale invasion of Cuba, and a naval blockade of the island. Kennedy eventually chose a blockade, or quarantine, of Cuba, backed up by the threat of imminent military action. In announcing his decision on national television on October 22, 1962—breaking the extraordinary secrecy surrounding the crisis to that point—Kennedy warned that the purpose of the Soviet missiles in Cuba could be “none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere” and that he would protect the United States from such a threat no matter what the cost. The lines, suddenly, were drawn very firmly indeed, and the world held its breath.

After several days of action and reaction, each seeming to bring the world closer to the brink of nuclear war, the two sides reached a deal. Khrushchev would order the withdrawal of offensive missiles, and Kennedy would promise not to invade Cuba; Kennedy also secretly promised to withdraw American ballistic nuclear missiles based in Turkey targeting the Soviet Union. Difficult negotiations aimed at finalizing the deal and verifying its implementation dragged on for several weeks but, on November 20, 1962, Kennedy finally ordered the lifting of the naval blockade of Cuba.

To the Moon

Kennedy was also instrumental in the success of the nation's space program. An enthusiastic proponent of it in public, if dubious of its more scientific dimensions in private, he vowed to have Americans on the moon by the end of the decade. Although the rockets would be launched from Cape Canaveral in Florida, Kennedy agreed to locate the headquarters of the Manned Spacecraft Center in Texas, the home state of his vice president; Lyndon Johnson had previously been head of the Senate subcommittee in charge of funding the space program. Kennedy would not live to see the landing of a man on the moon in July 1969.

The Developing World

President Kennedy created the Peace Corps by executive order in 1961, a reaction to both the growing spirit of activism throughout the West and Communist efforts to capitalize on the decolonization process. Through the promotion of modernization and development, Peace Corps volunteers sought to improve social and economic conditions throughout the world; their work also supported Kennedy’s efforts in the Cold War battle for hearts and minds. In September 1961, shortly after Congress formally endorsed the Peace Corps by making it a permanent program, the first volunteers went abroad to teach English in Ghana. Contingents of aid workers soon followed to Tanzania and India. The program proved enduring; by the end of the twentieth century, the Peace Corps had sent more than 170,000 American volunteers to over 135 nations.

Fears that Castro’s example might inspire Communist revolution throughout Latin America led Kennedy to offer a more specific program for hemispheric reform. The Alliance for Progress, announced in March 1961, comprised a series of measures to improve the region's social and economic fortunes. This charter—and the US financial aid that came with it—sought to improve America's standing in the region, though few Latin nations agreed with the US embargo on Cuba or cooperated with it.

Southeast Asia

Although Laos presented Kennedy with an initial (and recurring) challenge in the region, by the end of his presidency it was Vietnam that proved at least as difficult, and potentially more dangerous. America had been sending military advisers to Saigon since the early 1950s to help France in its war against Vietnamese Communists for control of the nation. In 1961, Kennedy increased this allotment and ordered in the Special Forces, an elite army unit, to train the South Vietnamese in counter-insurgency warfare. But war continued to spread, and by the end of Kennedy's presidency, 16,000 American military advisers were serving in Vietnam.

As with other aspects of his administration, it is not clear how Kennedy would have handled America's growing commitment to Vietnam had he lived out his term in office. Kennedy had announced plans in 1963 to reduce the number of American advisers, but this did not necessarily mean a reduction in the US commitment. The announcement was one of several measures designed to pressure Saigon into making reforms. Instead, the regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem continued its repression of political opponents. Diem was assassinated in November 1963 in a military coup, an act that perpetuated, and arguably exacerbated, the country’s political instability.

Limiting Nuclear Testing

Just months before his death, Kennedy secured an agreement, with Britain and the Soviet Union, to limit the testing of nuclear weapons in space, underwater, and in the earth's atmosphere. Not only did it seek to reduce hazardous nuclear “fallout,” it also signaled the success of Kennedy's efforts to engage the Soviet Union in constructive negotiations and reduce Cold War tensions, a goal captured most famously in his June 1963 remarks at American University. In the wake of the close call over Cuba, Kennedy considered this agreement his greatest accomplishment as president.