Presidents on health care

Every administration since FDR's New Deal has had to consider the appropriate role of government in securing the nation's health

Franklin Roosevelt | Harry Truman | Dwight Eisenhower | John Kennedy | Lyndon Johnson | Richard Nixon | Gerald Ford | Jimmy Carter | Ronald Reagan

Franklin Roosevelt

FDR took office on March 1, 1933, amid an economic catastrophe and pledged to lead “this great army of our people dedicated to a disciplined attack upon our common problems," asserting that "our Constitution is so simple and practical that it is possible always to meet extraordinary needs by changes in emphasis and arrangement without loss of essential form.” During his time in office he came to argue that freedom included “freedom from want.” His New Deal, however, steered clear of pushing the government into health care.

In a 1934 speech, for instance, he asserted, “On some points it is possible to be definite. Unemployment insurance will be in the program. I am still of the opinion expressed in my message of June eighth that this part of social insurance should be a cooperative federal-state undertaking.” In contrast, of national health insurance he said, “Whether we came to this form of insurance soon or later on I am confident that we can devise a system which will enhance and not hinder the remarkable progress which has been made and is being made in the practice of the professions of medicine and surgery in the United States.”

Similarly, in his 1941 State of the Union, Roosevelt was quite specific that “we should bring more citizens under the coverage of old-age pensions and unemployment insurance" while keeping health care objectives vague: “We should widen the opportunities for adequate medical care.”

For more detail: Kooijman, Jaap. “Soon or Later On: Franklin D. Roosevelt and National Health Insurance, 1933-1945.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 29, no. 2 (1999): 336–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27551992.

Harry Truman

After seeing the United States through to the end of World War II, Harry Truman faced the question of how to approach his predecessor's New Deal legacy. In September 1945, he made clear his intentions when he delivered a rambling 21-point economic plan that called for new public works programs, legislation guaranteeing "full employment," a higher minimum wage, extension of the Fair Employment Practices Committee, a larger Social Security System, and a national health insurance system. Two months later, he delivered a Special Message to the Congress Recommending a Comprehensive Health Program, in which he said, “In the past, the benefits of modern medical science have not been enjoyed by our citizens with any degree of equality. Nor are they today. Nor will they be in the future—unless government is bold enough to do something about it.”

After seeing the United States through to the end of World War II, Harry Truman faced the question of how to approach his predecessor's New Deal legacy. In September 1945, he made clear his intentions when he delivered a rambling 21-point economic plan that called for new public works programs, legislation guaranteeing "full employment," a higher minimum wage, extension of the Fair Employment Practices Committee, a larger Social Security System, and a national health insurance system. Two months later, he delivered a Special Message to the Congress Recommending a Comprehensive Health Program, in which he said, “In the past, the benefits of modern medical science have not been enjoyed by our citizens with any degree of equality. Nor are they today. Nor will they be in the future—unless government is bold enough to do something about it.”

Truman laid out his preferred plan for how a national health system would work:

Everyone should have ready access to all necessary medical, hospital and related services.

I recommend solving the basic problem by distributing the costs through expansion of our existing compulsory social insurance system. This is not socialized medicine.

Everyone who carries fire insurance knows how the law of averages is made to work so as to spread the risk, and to benefit the insured who actually suffers the loss. If instead of the costs of sickness being paid only by those who get sick, all the people—sick and well—were required to pay premiums into an insurance fund, the pool of funds thus created would enable all who do fall sick to be adequately served without overburdening anyone. That is the principle upon which all forms of insurance are based.

During the past fifteen years, hospital insurance plans have taught many Americans this magic of averages. Voluntary health insurance plans have been expanding during recent years; but their rate of growth does not justify the belief that they will meet more than a fraction of our people's needs. Only about 3% or 4% of our population now have insurance providing comprehensive medical care.

A system of required prepayment would not only spread the costs of medical care, it would also prevent much serious disease. Since medical bills would be paid by the insurance fund, doctors would more often be consulted when the first signs of disease occur instead of when the disease has become serious. Modern hospital, specialist and laboratory services, as needed, would also become available to all, and would improve the quality and adequacy of care. Prepayment of medical care would go a long way toward furnishing insurance against disease itself, as well as against medical bills.

Such a system of prepayment should cover medical, hospital, nursing and laboratory services. It should also cover dental care—as fully and for as many of the population as the available professional personnel and the financial resources of the system permit.

The ability of our people to pay for adequate medical care will be increased if, while they are well, they pay regularly into a common health fund, instead of paying sporadically and unevenly when they are sick. This health fund should be built up nationally, in order to establish the broadest and most stable basis for spreading the costs of illness, and to assure adequate financial support for doctors and hospitals everywhere. If we were to rely on state-by-state action only, many years would elapse before we had any general coverage. Meanwhile health service would continue to be grossly uneven, and disease would continue to cross state boundary lines.

Medical services are personal. Therefore the nation-wide system must be highly decentralized in administration. The local administrative unit must be the keystone of the system so as to provide for local services and adaptation to local needs and conditions. Locally as well as nationally, policy and administration should be guided by advisory committees in which the public and the medical professions are represented.

Subject to national standards, methods and rates of paying doctors and hospitals should be adjusted locally. All such rates for doctors should be adequate, and should be appropriately adjusted upward for those who are qualified specialists.

People should remain free to choose their own physicians and hospitals. The removal of financial barriers between patient and doctor would enlarge the present freedom of choice. The legal requirement on the population to contribute involves no compulsion over the doctor's freedom to decide what services his patient needs. People will remain free to obtain and pay for medical service outside of the health insurance system if they desire, even though they are members of the system; just as they are free to send their children to private instead of to public schools, although they must pay taxes for public schools.

Likewise physicians should remain free to accept or reject patients. They must be allowed to decide for themselves whether they wish to participate in the health insurance system full time, part time, or not at all. A physician may have some patients who are in the system and some who are not. Physicians must be permitted to be represented through organizations of their own choosing, and to decide whether to carry on in individual practice or to join with other doctors in group practice in hospitals or in clinics.

Our voluntary hospitals and our city, county and state general hospitals, in the same way, must be free to participate in the system to whatever extent they wish. In any case they must continue to retain their administrative independence.

Voluntary organizations which provide health services that meet reasonable standards of quality should be entitled to furnish services under the insurance system and to be reimbursed for them. Voluntary cooperative organizations concerned with paying doctors, hospitals or others for health services, but not providing services directly, should be entitled to participate if they can contribute to the efficiency and economy of the system.

None of this is really new. The American people are the most insurance-minded people in the world. They will not be frightened off from health insurance because some people have misnamed it “socialized medicine.”

I repeat—what I am recommending is not socialized medicine.

Socialized medicine means that all doctors work as employees of government. The American people want no such system. No such system is here proposed.

. . .

Premiums for present social insurance benefits are calculated on the first $3,000 of earnings in a year. It might be well to have all such premiums, including those for health, calculated on a somewhat higher amount such as $3,600.

A broad program of prepayment for medical care would need total amounts approximately equal to 4% of such earnings. The people of the United States have been spending, on the average, nearly this percentage of their incomes for sickness care. How much of the total fund should come from the insurance premiums and how much from general revenues is a matter for the Congress to decide.

The plan which I have suggested would be sufficient to pay most doctors more than the best they have received in peacetime years. The payments of the doctors' bills would be guaranteed, and the doctors would be spared the annoyance and uncertainty of collecting fees from individual patients. The same assurance would apply to hospitals, dentists and nurses for the services they render.

Federal aid in the construction of hospitals will be futile unless there is current purchasing power so that people can use these hospitals. Doctors cannot be drawn to sections which need them without some assurance that they can make a living. Only a nation-wide spreading of sickness costs can supply such sections with sure and sufficient purchasing power to maintain enough physicians and hospitals.

We are a rich nation and can afford many things. But ill-health which can be prevented or cured is one thing we cannot afford.

Like much of Truman's program, his plan to insure Americans went nowhere. Still, he continued to make the case, offering another special message to Congress on the subject in May 1947, “The total health program which I have proposed is crucial to our national welfare. The heart of that program is national health insurance. Until it is a part of our national fabric, we shall be wasting our most precious national resource and shall be perpetuating unnecessary misery and human suffering.” And on the 1948 campaign trail he said, “Only 20 percent–one-fifth of our population is able to afford the medical care they need. Now that means that there are 110 million people in this country who can’t afford proper medical attention. That is a disgrace to the richest country in the world.”

The Board of Trustees of the American Medical Association has approved the expenditure in October of $1,100,000 in a newspaper and radio advertising campaign in an effort to deliver a knockout blow to the Administration pro gram for compulsory health insurance.

William Laurence, New York Times, June 27, 1950

Following a surprising and close victory in the 1948 election (he won a plurality but not a majority of the popular vote) Truman continued to argue for national health insurance:

- Many people are concerned about the cost of a national health program. The truth is that it will save a great deal more than it costs. We are already paying about four per cent of our national income for health care. More and better care can be obtained for this same amount of money under the program I am recommending. Furthermore, we can and should invest additional amounts in an adequate health program-for the additional investment will more than pay for itself. [April 22, 1949]

- Now, personally, I have always understood that the Constitution of the United States imposes upon the Government of the United States a responsibility with respect to the general welfare of its citizens. And certainly no one can pretend that good health is not a matter of first importance so far as the general welfare is concerned. That is why, ever since I have been President, I have recommended programs which I believe will provide better medical and health services for all our people. Some groups have received these proposals enthusiastically. Others have been strongly against them. [September 16, 1952]

- The health of the American people is one of our basic national resources. It is as important to the welfare of our country as our land, our water, and our minerals. Our National Government has been concerned about the preservation and development of these resources for decades. It is just as logical, and just as important, for us to be concerned about health. [November 19, 1952]

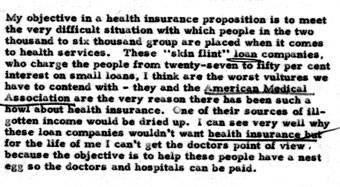

Ultimately, Truman had to admit defeat, writing towards the end of his presidency, “These ‘skin flint’ loan companies who charge the people from twenty-seven to fifty per cent interest on small loans, I think are the worst vultures we have to contend with—they and the American Medical Association are the very reason there has been such a howl about health insurance. One of their sources of ill-gotten income would be dried up. I can see very well why these loan companies wouldn't want health insurance but for the life of me I can't get the doctors [sic] point of view because the objective is to help these people have a nest egg so the doctors and hospitals can be paid.”

Dwight Eisenhower

During his successful 1952 campaign for the presidency, Dwight Eisenhower stated his opposition to “socialized medicine,” a reflection of the language used to defeat Truman's comprehensive national health insurance plan. But Ike, assumed by many Democrats before the 1948 campaign to be one of them, considered himself a “modern Republican.” He had no desire to roll back the New Deal even as he criticized Truman's plans to expand it. He signed legislation that expanded Social Security, increased the minimum wage, and created the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and he championed increased investment in the nation's infrastructure. His goals for health care were more restrained, but even as a candidate he balanced his opposition to government intervention in the health care system with the observation that, “Too many of our people live too far from adequate medical aid; too many of our people find the cost of adequate medical care too heavy.”

During his successful 1952 campaign for the presidency, Dwight Eisenhower stated his opposition to “socialized medicine,” a reflection of the language used to defeat Truman's comprehensive national health insurance plan. But Ike, assumed by many Democrats before the 1948 campaign to be one of them, considered himself a “modern Republican.” He had no desire to roll back the New Deal even as he criticized Truman's plans to expand it. He signed legislation that expanded Social Security, increased the minimum wage, and created the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and he championed increased investment in the nation's infrastructure. His goals for health care were more restrained, but even as a candidate he balanced his opposition to government intervention in the health care system with the observation that, “Too many of our people live too far from adequate medical aid; too many of our people find the cost of adequate medical care too heavy.”

During his 1954 State of the Union, Eisenhower professed his faith that “The great need for hospital and medical services can best be met by the initiative of private plans.” But he did suggest a role for the Federal Government.

It is unfortunately a fact that medical costs are rising and already impose severe hardships on many families. The Federal Government can do many helpful things and still carefully avoid the socialization of medicine. The Federal Government should encourage medical research in its battle with such mortal diseases as cancer and heart ailments, and should continue to help the states in their health and rehabilitation programs. The present Hospital Survey and Construction Act should be broadened in order to assist in the development of adequate facilities for the chronically ill, and to encourage the construction of diagnostic centers, rehabilitation facilities, and nursing homes. The war on disease also needs a better working relationship between Government and private initiative. Private and non-profit hospital and medical insurance plans are already in the field, soundly based on the experience and initiative of the people in their various communities. A limited Government reinsurance service would permit the private and non-profit insurance companies to offer broader protection to more of the many families which want and should have it.

On January 31, 1955, Eisenhower offered a Special Message to the Congress Recommending a Health Program:

I recommend, consequently, the establishment of a Federal health reinsurance service to encourage private health insurance organizations in offering broader benefits to insured individuals and families and coverage to more people.

In addition, to improve medical care for the aged, the blind, dependent children, and the permanently and totally disabled who are public assistance recipients, I recommend the authorization of limited Federal grants to match State and local expenditures.

Reinsurance: The purpose of the reinsurance proposal is to furnish a system for broad sharing among health insurance organizations of the risks of experimentation. A system of this sort will give an incentive to the improvement of existing health insurance plans. It will encourage private, voluntary health insurance organizations to provide better protection—particularly against expensive illness—for those who now are insured against some of the financial hazards of illness. Reinsurance will also help to stimulate extension of private voluntary health insurance plans to millions of additional people who do not now have, but who could afford to purchase, health insurance.

The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare has been working with specialists from the insurance industry, with experts from the health professions, and with many other interested citizens, in its effort to perfect a sound reinsurance program—a program which involves no Government subsidy and no government competition with private insurance carriers. The time has come to put such a program to work for the American people.

I urge the Congress to launch the reinsurance service this year by authorizing a reasonable capital fund and by providing for its use as necessary to reinsure three broad areas for expansion in private voluntary health insurance:

1. health insurance plans providing protection against the high costs of severe or prolonged illness,

2. health insurance plans providing coverage for individuals and families in predominantly rural areas,

3. health insurance plans designed primarily for coverage of individuals and families of average or lower income against medical care costs in the home and physician's office as well as in the hospital.

Medical care [or public assistance recipients. Nearly 5 million persons in the United States are now receiving public assistance under State programs aided by Federal grants. Present arrangements for their medical care, however, are far from adequate. Special provision for improving health services for these needy persons must be made.

I recommend to the Congress, therefore, that it authorize separate Federal matching of State and local expenditures for the medical care needed by public assistance recipients. The separate matching should apply to each of the four Federally-aided categories--the aged, the permanently and totally disabled, the blind and children deprived of parental care.

Though Ike did succeed in providing tax cuts for employers who gave their workers health insurance, the national reinsurance plan was not a priority and was never realized.

For more detail:

Derickson, Alan, “Health Security for All? Social Unionism and Universal Health Insurance, 1935-1958” Journal of American History 80, no. 4 (Mar., 1994): 1333-1356. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2080603

Graham, Jordan M., "We Are Against Socialized Medicine, But What Are We For?: Federal Health Reinsurance, National Health Policy, and the Eisenhower Presidency" (2015). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4492.

https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4492

John Kennedy

JFK's narrow victory over Eisenhower's vice president, Richard Nixon, gave him the opportunity to pursue a domestic agenda he called the “New Frontier.”B Kennedy was unable to call on the Democratic majority in Congress to support his most progressive legislative reforms, with many Southerners in his own party deeply suspicious of him. Among other social programs, he proposed medical care for the elderly through an expansion of Social Security.

What we are now talking about doing, most of the countries of Europe did years ago.

Kennedy took his case to the American public through a rally held at Madison Square Garden in New York on May 20, 1962.

As were his predecessors, however, the president was at odds with the American Medical Association, which again launched a campaign against “socialized medicine.” When the bill failed in July by two votes in the Senate, JFK was left to lament, “I believe this is a most serious defeat for every American family, for the 17 million Americans who are over 65, whose means of support, whose livelihood, is certainly lessened over what it was in their working days, who are more inclined to be ill, who are more likely to be in hospitals, who are less able to pay their bills.”

Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Johnson assumed the presidency following the stunning assassination of his predecessor, and his first months in office would be oriented by JFK's policies. But having felt sidelined as vice president, Johnson was anxious to put his formidable political skills to work, to succeed where Kennedy had not. “I do understand power,” he once said about himself. “I know where to look for it, and how to use it.” He swiftly moved beyond the Kennedy legacy to an ambitious domestic agenda he called “The Great Society.” Among other issues, health care was squarely in his sights.

Rather than address the health care system as a whole, Johnson pushed for the passage of Medicare for the elderly before the 1964 election. He was unsuccessful in the short-term but used the issue in his campaign against Barry Goldwater.

After Johnson's landslide victory, passage of national health insurance for the elderly appeared imminent. The idea was popular, Democrats held solid majorities in both houses of Congress, and moderate Republicans were seeking to move toward the political center. Still, the particular form of the program, how much it would cost, and how it would be payed for were very much up for debate—and there were several proposals circulating around Capitol Hill.

You just tell them not to let it lay around; they can do that if they want to, but they might not. Then that gets the doctors organized, then they get the others organized, and they damn near killed my education bill lettin’ it lay around. And it stinks. It’s just like a dead cat on the door. When the committee reports it, you better either bury that cat or give it some life.

Lyndon Johnson, pushing for passage of Medicare, March 3, 1965

Republicans criticized the lack of coverage for physicians' fees and prescriptions and offered plans to add those benefits. Other members were concerned that the rising costs of health care would leave the Social Security trust fund vulnerable. Thus in its final form, the bill included coverage of physicians' fees and provided for a separate trust fund for Medicare. And to decrease the opposition of the AMA, the final bill left physicians and insurance companies with a substantial amount of control over fees. But Johnson also was able to include Medicaid, which covered poorer Americans. Thus, much like Civil Rights, his final triumph went beyond what Kennedy had proposed.

On July 30, 1965, Johnson traveled to the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum in Independence, Missouri, to sign the bill and pay homage to the man who had pushed so hard for a Federal health plan. He presented the first two Medicare cards to President Truman and his wife, Bess, and addressed his remarks to the 33rd president and tracing the roots of the bill back to FDR.

There are more than 18 million Americans over the age of 65. Most of them have low incomes. Most of them are threatened by illness and medical expenses that they cannot afford.

And through this new law, Mr. President, every citizen will be able, in his productive years when he is earning, to insure himself against the ravages of illness in his old age.

This insurance will help pay for care in hospitals, in skilled nursing homes, or in the home. And under a separate plan it will help meet the fees of the doctors.

Now here is how the plan will affect you:

During your working years, the people of America—you—will contribute through the social security program a small amount each payday for hospital insurance protection. For example, the average worker in 1966 will contribute about $1.50 per month. The employer will contribute a similar amount. And this will provide the funds to pay up to 90 days of hospital care for each illness, plus diagnostic care, and up to 100 home health visits after you are 65. And beginning in 1967, you will also be covered for up to 100 days of care in a skilled nursing home after a period of hospital care.

And under a separate plan, when you are 65—that the Congress originated itself, in its own good judgment—you may be covered for medical and surgical fees whether you are in or out of the hospital. You will pay $3 per month after you are 65 and your Government will contribute an equal amount.

The benefits under the law are as varied and broad as the marvelous modern medicine itself. If it has a few defects—such as the method of payment of certain specialists-then I am confident those can be quickly remedied and I hope they will be.

No longer will older Americans be denied the healing miracle of modern medicine. No longer will illness crush and destroy the savings that they have so carefully put away over a lifetime so that they might enjoy dignity in their later years. No longer will young families see their own incomes, and their own hopes, eaten away simply because they are carrying out their deep moral obligations to their parents, and to their uncles, and their aunts.

And no longer will this Nation refuse the hand of justice to those who have given a lifetime of service and wisdom and labor to the progress of this progressive country.

And this bill, Mr. President, is even broader than that. It will increase social security benefits for all of our older Americans. It will improve a wide range of health and medical services for Americans of all ages.

In 1935 when the man that both of us loved so much, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, signed the Social Security Act, he said it was, and I quote him, "a cornerstone in a structure which is being built but it is by no means complete."

Well, perhaps no single act in the entire administration of the beloved Franklin D. Roosevelt really did more to win him the illustrious place in history that he has as did the laying of that cornerstone. And I am so happy that his oldest son Jimmy could be here to share with us the joy that is ours today. And those who share this day will also be remembered for making the most important addition to that structure, and you are making it in this bill, the most important addition that has been made in three decades.

Richard Nixon

Now it is time that we move forward again in still another critical area: health care.

Richard Nixon tried not once, but twice to make major changes to the American health care system. A mandate for employer-provided heath insurance was a key foundations of his 1971 health strategy. During his State of the Union address in January, Nixon set out his goals:

I will offer a far-reaching set of proposals for improving America's health care and making it available more fairly to more people.

I will propose:

—A program to insure that no American family will be prevented from obtaining basic medical care by inability to pay.

—I will propose a major increase in and redirection of aid to medical schools, to greatly increase the number of doctors and other health personnel.

—Incentives to improve the delivery of health services, to get more medical care resources into those areas that have not been adequately served, to make greater use of medical assistants, and to slow the alarming rise in the costs of medical care.

—New programs to encourage better preventive medicine, by attacking the causes of disease and injury, and by providing incentives to doctors to keep people well rather than just to treat them when they are sick.

I will also ask for an appropriation of an extra $100 million to launch an intensive campaign to find a cure for cancer, and I will ask later for whatever additional funds can effectively be used. The time has come in America when the same kind of concentrated effort that split the atom and took man to the moon should be turned toward conquering this dread disease. Let us make a total national commitment to achieve this goal.

America has long been the wealthiest nation in the world. Now it is time we became the healthiest nation in the world.

Nixon's initial proposal included the following:

- Employers would be required to provide basic health insurance with specific coverage requirements.

- Employees would share the cost up to a cap.

- For the self-employed and others, special insurance programs at reasonable rates would be made available.

- A completely federal plan open to any family below a certain income level would replace Medicaid—cost-sharing would rise with income.

Nixon's efforts during his first term, however, went nowhere.

In 1974, following his re-election, like Truman before him, he tried again. When he launched the effort in his State of the Union, however, he was at pains to suggest that no taxes would be required and that he would not “put our whole health care system under the heavy hand of the Federal government.” And in February, Nixon delivered a Special Message to the Congress Proposing a Comprehensive Health Insurance Plan—the third special message on health care of his presidency.

Beyond the question of the prices of health care, our present system of health care insurance suffers from two major flaws :

First, even though more Americans carry health insurance than ever before, the 25 million Americans who remain uninsured often need it the most and are most unlikely to obtain it. They include many who work in seasonal or transient occupations, high-risk cases, and those who are ineligible for Medicaid despite low incomes.

Second, those Americans who do carry health insurance often lack coverage which is balanced, comprehensive and fully protective:

—Forty percent of those who are insured are not covered for visits to physicians on an out-patient basis, a gap that creates powerful incentives toward high cost care in hospitals;

—Few people have the option of selecting care through prepaid arrangements offered by Health Maintenance Organizations so the system at large does not benefit from the free choice and creative competition this would offer;

—Very few private policies cover preventive services;

—Most health plans do not contain built-in incentives to reduce waste and inefficiency. The extra costs of wasteful practices are passed on, of course, to consumers; and

—Fewer than half of our citizens under 65—and almost none over 65—have major medical coverage which pays for the cost of catastrophic illness.

These gaps in health protection can have tragic consequences. They can cause people to delay seeking medical attention until it is too late. Then a medical crisis ensues, followed by huge medical bills—or worse. Delays in treatment can end in death or lifelong disability.

COMPREHENSIVE HEALTH INSURANCE PLAN (CHIP)

Early last year, I directed the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to prepare a new and improved plan for comprehensive health insurance. That plan, as I indicated in my State of the Union message, has been developed and I am presenting it to the Congress today. I urge its enactment as soon as possible.

The plan is organized around seven principles:

First, it offers every American an opportunity to obtain a balanced, comprehensive range of health insurance benefits;

Second, it will cost no American more than he can afford to pay;

Third, it builds on the strength and diversity of our existing public and private systems of health financing and harmonizes them into an overall system;

Fourth, it uses public funds only where needed and requires no new Federal taxes;

Fifth, it would maintain freedom of choice by patients and ensure that doctors work for their patient, not for the Federal Government.

Sixth, it encourages more effective use of our health care resources;

And finally, it is organized so that all parties would have a direct stake in making the system work--consumer, provider, insurer, State governments and the Federal Government.

By August, Watergate had consumed the Nixon presidency, and with it, any hopes for health care reform.

Gerald Ford

Nixon's vice president, Gerald Ford, had a host of problems to consider when he assumed the presidency on August 9, 1974, not least of which was to restore the nation's trust in the highest office in the land. Three days later, in an address to a joint session of Congress, Ford kept his plans vague, saying, “As vice president, I studied various proposals for better health care financing. I saw them coming closer together and urged my friends in the Congress and in the administration to sit down and sweat out a sound compromise. The comprehensive health insurance plan goes a long ways toward providing early relief to people who are sick. Why don't we write—and I ask this with the greatest spirit of cooperation—why don't we write a good health bill on the statute books in 1974, before this Congress adjourns?”

We cannot realistically afford federally dictated national health insurance providing full coverage for all 215 million Americans.

Further efforts on health care were similarly restrained. Inflation began to soar in the Ford years, and it is not surprising that he saw the issue through the lens of cost. In his 1976 State of the Union, he focused more on health care costs than on quality or expansion of coverage.

Hospital and medical services in America are among the best in the world, but the cost of a serious and extended illness can quickly wipe out a family's lifetime savings. Increasing health costs are of deep concern to all and a powerful force pushing up the cost of living. The burden of catastrophic illness can be borne by very few in our society. We must eliminate this fear from every family.

I propose catastrophic health insurance for everybody covered by Medicare. To finance this added protection, fees for short-term care will go up somewhat, but nobody after reaching age 65 will have to pay more than $500 a year for covered hospital or nursing home care, nor more than $250 for one year's doctor bills.

We cannot realistically afford federally dictated national health insurance providing full coverage for all 215 million Americans. The experience of other countries raises questions about the quality as well as the cost of such plans. But I do envision the day when we may use the private health insurance system to offer more middle-income families high quality health services at prices they can afford and shield them also from their catastrophic illnesses.

We have built a haphazard, unsound, undirected, inefficient nonsystem which has left us unhealthy and unwealthy at the same time.

Jimmy Carter, April 16, 1976

Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter ran for the presidency in 1976 at the head of a Democratic Party that had been pushing for a national health insurance plan during the early 1970s. At the head of the effort was Senator Edward Kennedy, who would become a major opponent of the president. Kennedy was passionate about his bill to establish a single-payer insurance system to cover all Americans, and had lined up supporters among labor unions and other core groups. During the campaign, Carter endorsed the idea, but once in office began to grapple with the financial and political realities. The issue brought out the stark personality differences between himself and Kennedy, who grew deeply frustrated at Carter's unwillingness to move decisively.

Everybody in the Democratic Party wanted a health care bill. The issue was what kind of a health care bill.

Joseph Califano, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1977–1979

Believing it was politically unfeasible to change the healthcare system in one fell swoop, Carter focused on a plan that would keep costs down and gradually cover all Americans, recalled Joseph Califano, Carter's secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, during his interview for the Miller Center's Edward M. Kennedy Oral History: "We would have combined Medicare and Medicaid into one program. The government would have paid for the poor and the old, and we would have mandated employers—starting the way [Franklin] Roosevelt started the minimum wage—we'd mandate the big employers, who were already providing more than the mandate, to provide mandated coverage, and then gradually, over a period of time, cover everybody.”

That wasn't good enough for Kennedy, who thought an incremental, piecemeal approach was a formula for failure. Though willing to negotiate with Carter, by 1978 the senator had broken with the president and prepared not only to introduce his own health care bill but also to mount a primary challenge to a second Carter term. Needless to say, there was no real way to pass legislation as the Carter years came to an end.

Stuart Eizenstat, a Carter assistant for domestic affairs and policy, pointed to something else. “It’s interesting and ironic that during a Republican President—Ford and then Nixon—you had a very activist Congress,” he told Miller Center historians during a Jimmy Carter Oral History interview. “And here a Democrat comes into office, committed to furthering that, and you’ve got a Democratic Congress which begins to resist. I think that what happened is that even though they were Democrats, they began to reflect what was happening out there in their districts, which was a growing sense of conservatism.”

Ronald Reagan

In the most well-known line of his inaugural address, Ronald Reagan expressed a philosophy diametrically opposed to the New Deal: “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” This move away from involving government in major problems had actually begun with his predecessor, Jimmy Carter, who had himself centered his most famous speech around a “growing crisis of confidence.” (In contrast, the 1972 Democratic standard-bearer George McGovern told Miller Center historians, “I’ve always thought that every major problem facing the United States cannot be solved without the full and active support of the United States government, and that far from being the problem, government is our only hope to deal with the healthcare crisis, the environmental crisis, educational problems, and other things.”)

Nonetheless, in a 1983 message to Congress, Reagan outlined his view of the health care issues facing the nation:

Rising health care costs are a problem that affects everyone. The elderly, who are covered by Medicare, face the threat of catastrophic illness expense, against which Medicare offers no protection. The poor on Medicaid have seen coverage reduced as States have been forced by rising costs to make cutbacks. Workers with employment-based health insurance have received lower cash wages, because of the unchecked cost increases for health benefits. Americans pay for health care costs in other hidden forms, including higher costs for the merchandise they buy, since the costs of employee health care benefits must be included in the price of products.

But he immediately added, “As is the case with many of our national difficulties, past Federal policy has been a part of the problem. These policies have thwarted normal incentives for efficiency in health care.”

The Reagan administration began by limiting Federal contributions to Medicare and Medicaid and pushing administration of the programs to the states through block grants. Reimbursement to providers was also limited to a set fee schedule based on geographic area.

Reagan did address a specific health care issue in his 1986 State of the Union: “After seeing how devastating illness can destroy the financial security of the family, I am directing the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Dr. Otis Bowen, to report to me by year end with recommendations on how the private sector and government can work together to address the problems of affordable insurance for those whose life savings would otherwise be threatened when catastrophic illness strikes.”

The result was the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988, which was intended to protect the elderly from the cost of ongoing hospital care, prescription drugs, and copayments to physicians. However, with beneficiaries paying a fee the additional coverage, the law came under criticism and was repealed the following year.

For more detail: Combs-Orme, Terri and Guyer, Bernard (1992) "America's Health Care System: The Reagan Legacy," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 19: Issue 1, Article 6. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol19/iss1/6