John F. Kennedy: Campaigns and Elections

The Campaign and Election of 1960

The election of 1960 brought to the forefront a generation of politicians born in the twentieth century, pitting the 47-year-old Republican vice president Richard M. Nixon against the 43-year-old Democratic challenger John F. Kennedy.

Kennedy's chief rival for the nomination was Hubert H. Humphrey from Minnesota, whose steadfast liberalism played well with many in the Midwest. The two fought it out in thirteen primaries. Humphrey's best hope rested on winning in his “back yard” of neighboring Wisconsin, and then painting himself as the new favorite. But Kennedy's superior planning, financing, and political instincts won out, and he beat Humphrey in his own region.

The nomination's turning point occurred in the West Virginia primary. A working-class, heavily Protestant state, West Virginia was critical for Kennedy, who had to show that a wealthy Catholic was electable there. Humphrey desperately threw all his remaining resources into the fray, even tapping a savings fund for his daughter's upcoming wedding. But the Kennedy machine overwhelmed him with money and savvy. In West Virginia, the only state in which it was legal for a campaign to pay workers and voters money for showing up at the polls, Kennedy's financing gave him a distinct advantage. Dispirited and broke, Humphrey abandoned the race.

At the Democratic National Convention held in Los Angeles in early July, Kennedy defeated his nearest rival, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, the Senate majority leader, on the first ballot. Kennedy then invited Johnson to become his running mate, a controversial move made ostensibly to placate the South, bypassing other party leaders such as Humphrey and Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri. In his acceptance speech, Kennedy pledged to “get the country moving again.” Americans, he said, stood “on the edge of New Frontier—of the 1960s—a frontier of unknown opportunities and perils—a frontier of unfilled hopes and threats.”

The Republicans, meeting a few weeks later in Chicago, nominated Nixon, making him the first vice president in the history of the modern two-party system to win the presidential nomination in his own right. Nixon chose Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the chief US delegate to the United Nations, as his running mate.

Once he had won the nomination of his party, Kennedy undertook the task of convincing American voters that he would make a better president than his rival. Kennedy cast himself as a Cold War liberal and promised to lead America out of what he called the “conservative rut” into which he accused Eisenhower, and by implication Nixon, of running the country. It was apparent throughout the campaign that the election would be close. A Gallup poll in late August put Nixon and Kennedy tied at 47 percent each, with 6 percent undecided.

Kennedy faced two great hurdles in his quest for the White House: his youth and his religion. Polls revealed that many Americans balked at the prospect of such a young man, untested on the world stage, leading the nation at a time of threatening Cold War peril, especially after Dwight Eisenhower, who projected a comforting grandfatherly image. For Nixon, although he was only four years older than Kennedy, this issue was less acute since he had the advantage of having served as vice president for the duration of Eisenhower's two terms and was therefore a more familiar face.

Even more unsettling to many Protestants was the prospect of a Roman Catholic, whom the Catholic Church might “control,” as the nation's president. Kennedy chose to tackle the religious issue openly and directly, giving a series of speeches designed to address any misgivings about his faith and voluntarily subjecting himself to a round of questioning about his views on church-state relations by leading Protestant clergy in Houston. The group's conclusion that they were satisfied with his answers provided a degree of comfort for many non-Catholic voters.

Televised Debates

In order to overcome Nixon's advantage in public recognition, Kennedy challenged Nixon to a series of televised debates. Nixon, an experienced debater, accepted. The series of debates between the two candidates became the first extensive use of what would thereafter become a staple medium of American political campaigns—television. Broadcast live on national television in late September and early October, the four debates ultimately provided the Kennedy campaign with a huge boost.

Seventy million people watched the first debate. The Richard Nixon that viewers saw on their black-and-white television sets appeared pallid, tense, and uncomfortable. Just out of the hospital for the treatment of an infected cut, he wore a light-colored suit that blended into the gray background; in combination with the harsh studio lighting that left Nixon perspiring, he offered a less-than commanding presence. By contrast, Kennedy appeared relaxed, tanned, and telegenic.

A mythology has taken root about post-debate opinion polls and their revelations about popular perceptions of the two candidates. Allegedly, those who had listened to the debates on the radio thought that Nixon had won, with the larger television audience being generally more impressed with Kennedy. No such comparative polls exist, however, and the market research on which those conclusions rest incorporated too few radio listeners to be statistically valid.

Both candidates traveled extensively and spent freely. Nixon, however, was hamstrung by an unfortunate early pledge to campaign in every state of the union. The trips to vote-poor states took precious time and money, while Kennedy focused his resources and time on the states with the most electoral college votes.

On Election Day, November 8, Kennedy won the popular vote by less than 120,000 votes out of a record 68.8 million ballots cast. Kennedy won the electoral college vote more clearly, winning 303 votes to Nixon's 219 (with Virginia's Harry F. Byrd winning 15). The closeness of the election naturally fueled speculation of tampering on both sides. In Chicago, Democratic mayor Richard Daley delivered an unusually good result for Kennedy—a result that came under scrutiny when Kennedy won Illinois by less than 9,000 votes. Citing voting irregularities, the Republican National Committee unsuccessfully challenged the Illinois vote in federal court, although Nixon carefully distanced himself from the various legal challenges presented by his party and his supporters. Suspicious results also emerged in Texas and elsewhere. Kennedy was initially believed to have won California, but after absentee ballots had been counted, that state's electors declared for Nixon.

Inauguration and Transition

On a cold January 20, 1961, John F. Kennedy took the oath of office. After such a close campaign, Kennedy knew his inaugural address would have to reach out to his opponents. In the days and weeks before it was to be delivered, he carefully studied famous American speeches, such as the Gettysburg Address, and copied their terse, vivid style. Departing from the pattern of many inaugural addresses, Kennedy pulled few punches and focused almost exclusively on matters outside the nation's borders. In addition, he claimed that his election signaled a fundamental generational shift in America:

“We observe today not a victory of party, but a celebration of freedom—symbolizing an end, as well as a beginning—signifying renewal, as well as change . . . Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage—and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this Nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world.”

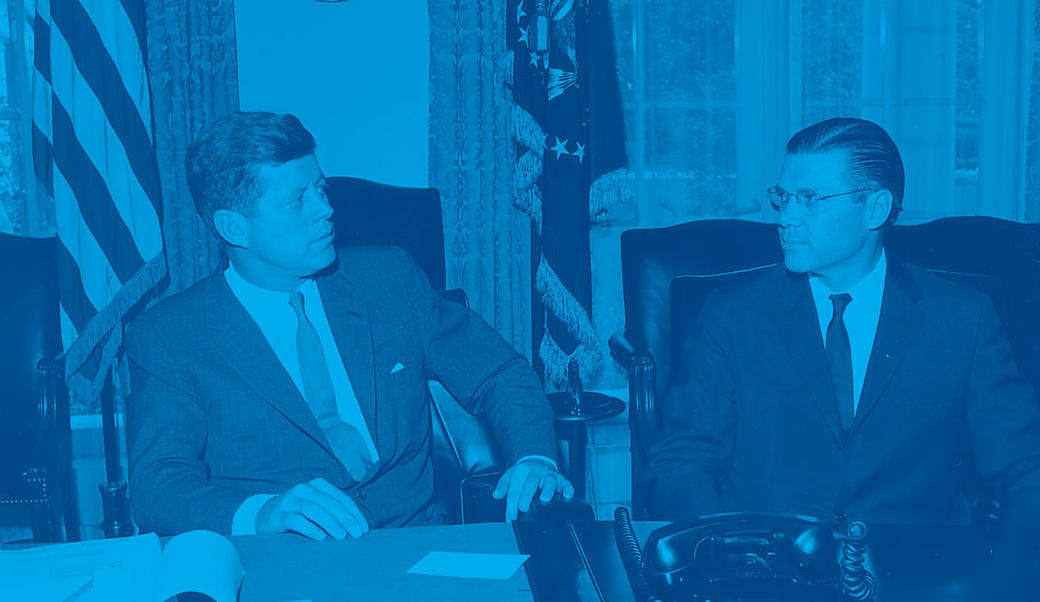

And he recalled the nation's revolutionary origins: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear in burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty.” In forming his administration, Kennedy surrounded himself with liberal intellectuals and, in light of the close popular vote, moderate conservatives espousing strong executive governance, rational planning, and a belief in the virtues of social science. An elite group of young, rich professionals, dubbed the “New Frontiersmen,” poured into Washington, adding to the tone of a White House seeking counsel from the nation's best and brightest.