[Reprinted from UVA Today]

Editor’s note: In honor of John F. Kennedy’s 100th birthday on May 29, Barbara Perry will co-host the panel discussion “JFK at 100: The Road to Camelot” on June 1 at 3 p.m. at the Miller Center.

When Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy presented to the federal government the deed to JFK’s Brookline, Massachusetts birthplace on what would have been his 52nd birthday in 1969, she pointed to the upstairs bedroom where she had given birth to the future president and recalled, “When you hold your baby in your arms the first time, and you think of all the things you can say and do to influence him, it’s a tremendous responsibility. What you do with him and for him can influence not only him, but everyone he meets, and not for a day or a month or a year, but for time and eternity.”

As the nation commemorates President Kennedy’s centennial on May 29th, it seems appropriate to ponder how his mother shaped his influential life.

Among her four sons, Rose had the most fraught relationship with Jack. Her Victorian perfectionism collided with his youthful rebelliousness. He chided her for frequent trips from home. “Gee, you’re a great mother to go away and leave your children alone,” the sickly boy observed. Yet, as an adult, he had to admit that she was the “glue” that held the family together.

Family patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. certainly molded his famous sons, Joe Jr., Jack, Bobby and Teddy, but if he was the family’s producer, Rose filled all the other credit lines in the Camelot play. As Teddy eulogized his parents, “Dad was the spark. Mother was the light of our lives. He was our greatest fan. She was our greatest teacher.”

What, then, were the lessons that Rose passed on to her father’s namesake, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, starting 100 years ago?

- Faith: JFK was not as openly devout as his brothers, walking the fine line between church and state on his way to becoming the nation’s first Roman Catholic president, but he observed the church’s traditions, if not all of its commandments. He attended weekly mass; recited prayers each night; wore a St. Christopher medal, along with his dog tags, into battle; and placed a similar amulet in his infant son’s casket four months before his own death.

- Sparkling wit: Rose could be an exacting taskmaster, but she leavened her convent-school discipline with a wry outlook on the world. Even as a young boy, Jack’s waggish humor reflected his mother’s Irish charm. He teased that his youngest brother, born on George Washington’s birthday, should be named for the first president, but he wrote more seriously from boarding school that he would like to be the infant’s godfather. JFK’s keen humor would become a hallmark of his presidential speeches and press conferences.

- Political DNA: JFK’s paternal grandfather practiced politics as a ward heeler and state legislator from East Boston, but the Kennedys’ genetic predisposition toward electoral politics came from Rose’s father, the legendary U.S. congressman and Boston mayor John F. (“Honey Fitz”) Fitzgerald. Grandson Jack practiced a more sophisticated, urbane style on the stump, but he first learned grassroots politicking at Honey Fitz’s elbow.

- Wanderlust: Although young Jack resented his mother’s penchant for travel, as a teen he followed in her footsteps, asking to study for a “gap year” in London, touring pre-WWII Europe and South America, serving as an aide during his father’s ambassadorship to England, and circling the globe to learn about the Cold War world. Foreign policy was his passion, sparked by Rose’s placing maps around the house and quizzing her children about geography.

- News obsession: Both Grandpa Fitzgerald and Rose clipped news stories from the daily papers and shared them with their offspring. Mrs. Kennedy tested her children’s knowledge of current events at the dinner table. Jack subscribed to the New York Times as a prep-school teen and briefly served as a reporter after WWII before creating news himself in Washington.

- Media savvy: As the daughter of Boston’s colorful mayor, Rose Fitzgerald grew up in the media spotlight, and she craved it as an adult. She passed along to Jack a talent for attracting news coverage.

- Love of history: Raised in the cradle of the American Revolution, Rose ensured that her children visited and had an appreciation for historic landmarks surrounding their childhood homes. Stories of American heroism would lead JFK to conceive his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Profiles in Courage.”

- Literary flair: All of the Kennedy children cherished their mother’s reading to them, but Jack particularly drew sustenance from literature as a distraction from his illnesses. Rose kept journals of eloquent passages that she eventually wove into her speeches on the campaign trail, and JFK could turn a phrase from his own pen or that of stellar wordsmith Ted Sorensen.

- Compelling public imagery: Although young JFK chafed under his mother’s strictures, her perfectionism created the famous images of her family, including their dazzling smiles, which readily captured the world’s imagination.

- Celebrity status: “Starstruck” came into usage in 1938, just as the Kennedy family became celebrities in pre-war London, but Rose had begun her lifelong hobby of autograph collecting as a young girl. Proximity to VIPs made her feel important, and her children reflected her admiration for monarchs, movie stars, sports heroes, religious and political leaders, literati and artists. Jack’s affiliation with Hollywood’s “Rat Pack,” led by Frank Sinatra, produced an aura that attracted men and women alike. “He’s better than Elvis!” shouted a co-ed at a Kennedy campaign rally. In the television era, such star power helped propel the handsome candidate to the White House.

During the Kennedy years, some Americans who had formerly felt the sting of discrimination made great breakthroughs in realizing the American Dream. For others, the early 1960s proved to be another disappointing era.

In 1963, President Kennedy initiated planning for what became the “War on Poverty.” He took these measures after reading an article by noted social commentator Michael Harrington entitled, “The Other America,” which detailed the plight of the poor. Kennedy ordered his economic advisers to consider new measures to deal with the one-fifth of the nation that had incomes below the poverty line. After Kennedy's death, President Lyndon B. Johnson moved to pick up Kennedy's poverty program, but also to massively expand it and elevate it among the priorities of his administration's domestic agenda.

In targeting poverty in America, Kennedy was motivated by more than a sense of “right” or responsibility (though those motivations arguably were important). In improving the lot of poor, Southern whites—particularly in Appalachia and the rural South—Kennedy hoped to win support of Southern members of Congress. By bringing these people into the mainstream, Kennedy also hoped to increase the Democratic electorate in the Southern and border states and stave off a Republican challenge to the party allegiance of white voters.

Changing Attitudes toward Religion

The 1960 election had thrust religion once again into the political debate. As a Catholic—the first ever to win the presidency—Kennedy implicitly challenged the religious status quo in American political life.

Kennedy gained much political support from Roman Catholics. Catholic votes for the Democratic ticket jumped when Kennedy ran for office. But some of this vote was a natural “rebound” after Catholic defections to Eisenhower; had Kennedy not been Catholic, it is arguable that he still would have won much of this vote. Kennedy's election effectively removed the taint of “dual loyalty” which falsely claimed that Catholics owed a political allegiance—and at times a primary allegiance—to the Pope in Rome. His family's good looks and culture broke stereotypes about Catholic ethnic groups consisting of uncultured and ignorant peasants. Like the Jews, Catholics in the second, third, and fourth generations were rapidly moving up in American society, and moving out from urban areas to the more affluent suburbs.

The Kennedy years also marked the advancement of Jews into high positions in government. Kennedy appointed Jews to his cabinet and to the federal courts, including the Supreme Court; some became close White House advisers. These years also signaled the beginning of the end of the routine exclusion of Jews from high corporate positions, country-club memberships, and exclusive residential neighborhoods, as well as the end of quotas on Jewish admissions to selective colleges and universities. It was no coincidence that many of Kennedy's most fervent backers were liberal Jewish intellectuals, particularly in the universities, and they flocked to be part of the Kennedy administration or serve as outside policy advisers.

Status of African Americans

African Americans were “the people left behind”: crowded into poorer neighborhoods, discriminated against, and actively prevented from obtaining good educations or jobs, victimized by criminals on the streets (and by unscrupulous merchants in stores), unprotected by the law or government. Kennedy had made many promises during the 1960 election that he would improve their lot.

As president, however, he moved slowly in this area. By distancing himself from civil rights leaders and only grudgingly pushing the federal government to protect civil rights workers, the Kennedy administration sent a signal to segregationists in the South that they could effectively defy the laws of the land. Kennedy promised during his election campaign to wipe out “with the stroke of a pen” discrimination in public housing by issuing executive orders. After months of delay, civil rights activists began sending pens to the White House to prod Kennedy to act. He eventually signed executive orders banning racial discrimination in wages by federal contractors, and in the sale, rental, or leasing of federal properties, but many observers remained disappointed in Kennedy's failure to act with more vigor to redress civil rights injustices.

Race Relations

The early 1960s political landscape was overwhelmingly white and middle class, a demographic that did not reflect accurately the breadth of American society. Race remained the great social, cultural, and economic divide. Puerto Ricans had moved into New York, Cuban exiles were flooding Miami, and Mexicans had been arriving in San Diego and Los Angeles for decades. But in absolute numbers and percentage, Hispanic Americans formed a negligible part of the population (perhaps 2 percent). They were an even smaller portion of the electorate and commanded little or no attention from national policymakers.

The “model minority” group was Asian: the Japanese Americans on the West Coast and the Chinese Americans on both coasts. The claim that there was “no juvenile delinquency” in their close-knit communities was a myth, but it symbolized a belief in stereotypes, shared by most Americans, that any racial and ethnic group could “make it” with hard work and the right attitude. The implicit contrast, of course, was with African Americans, particularly the “underclass” in the large cities. Lost in the contrast was the fact that poor Asian families, as well as black “strivers,” had succeeded in making it into the middle class—and higher. These stereotypes would later create racial tensions between Asian ethnic groups and African Americans. During the Kennedy years, there was essentially no national focus on issues involving Asian Americans, in part because these communities sought little government assistance or interference.

Advancement of Women

Reflecting the gender imbalance so notable in the Arthurian legend of Camelot with which it was later often associated (for different reasons), the Kennedy presidency failed to secure full equal opportunity for women, even as JFK backed the Equal Pay Act and sanctioned a commission on the status of women. During the Kennedy years, women continued to marry early, have children early, and defer to the career demands of the men in their lives. This dynamic seemed particularly relevant for the circle of high officials in the Kennedy administration. Kennedy's “New Frontiersmen” were just that—for the most part men—and women made few gains in federal office during his tenure. Most women who worked in politics in the New Frontier were on the fringes and in subordinate roles. The unmarried women took these roles as a prelude to their later careers as wives; the wives for the most part took on the roles of mothers and hostesses. Even though birth control pills, a factor usually identified as a prime catalyst for the gains of the women's movement, were introduced in the early 1960s, serious challenges to the subordinate status of women did not come until later in the decade.

John F. Kennedy had promised much but never had the opportunity to see his program through. It was, in the words of one notable biographer, “an unfinished life.” For that reason, assessments of the Kennedy presidency remain mixed.

Kennedy played a role in revolutionizing American politics. Television began to have a real impact on voters and long, drawn-out election campaigns became the norm. Style became an essential complement to substance.

Before winning the presidency, Kennedy had lived a life of privilege and comfort, and his relatively short congressional career had been unremarkable. Many voters yearned for the dynamism that Kennedy's youth and politics implied, but others worried that Kennedy's inexperience made him a poor choice to lead the nation during such a challenging time.

Early errors in judgment, particularly in the Bay of Pigs fiasco, seemingly confirmed these fears. By the summer of 1962, the administration was in trouble. A particularly difficult Cold War climate abroad, an antagonistic Congress at home, increasingly bold activist groups agitating for change, and a discouraging economic outlook all contributed to an increasingly negative view of the Kennedy White House.

That impression began to change in the fall of 1962. Skillful statesmanship—and some luck—led to notable success in the showdown over Cuba. The economic situation improved. Long-running, difficult negotiations finally resulted in a partial nuclear test ban treaty. And the work of civil rights activists and the occasional limited intervention of the federal government were slowly, but nevertheless steadily, wearing down the power of Southern segregationists.

But serious issues remained. Throughout the summer and fall of 1963, the situation in South Vietnam deteriorated; by the end of Kennedy's presidency, 16,000 US military “advisers” had been dispatched to the country. More importantly, the administration apparently had no realistic plan to resolve the conflict. In the area of civil rights, some progress had been achieved, but these successes had come mostly in spite of—not because of—the White House. Bloody conflict was becoming more prevalent on America's streets, and racial injustice remained rampant.

Assessments of Kennedy's presidency have spanned a wide spectrum. Early studies, the most influential of which were written by New Frontiersmen close to Kennedy, were openly admiring. They built upon on the collective grief from Kennedy's public slaying—the quintessential national trauma. Later, many historians focused on the seedier side of Kennedy family dealings and John Kennedy's questionable personal morals. More recent works have tried to find a middle ground.

In nation's popular memory, Kennedy still commands fascination as a compelling, charismatic leader during a period of immense challenge to the American body politic.

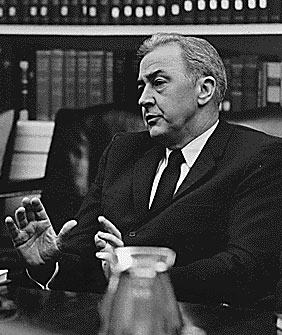

On November 22, 1963, John F. Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas, Texas. The event thrust Lyndon Johnson into the presidency. A man widely considered to be one of the most expert and brilliant politicians of his time, Johnson would leave office a little more than five years later as one of the least popular Presidents in American history. The man who had risen from the poor Hill Country of Texas to become the acknowledged leader of the United States Senate and occupant of the Oval Office would return to Texas demoralized and discredited. He died four years later, a few hundred feet from the place of his birth.

As a man, Lyndon Johnson was obsessed with his place in history, consumed by a voracious appetite for life, and often cast between emotional extremes. He was a natural politician, and to many people who knew him, he seemed larger than life. As a President, Johnson revealed that he was even more complex and ambitious, unveiling a sweeping collection of legislative and social initiatives he called "The Great Society." Elected in his own right by a landslide victory in 1964, he seemed unsinkable but soon floundered amid the Vietnam War. Vietnam—perhaps the most divisive event in American life since the Civil War—polarized the country and transformed political, strategic, and moral debates. President Johnson was unable to devise a strategy for victory, withdrawal, or peace with honor. In 1968, facing strong opposition to his renomination, Johnson declined to seek a second term. He left to his successor the problems of Vietnam, racial unrest, and unresolved issues of income inequality and erratic economic performance.

Education and Marriage

The Johnson family had been in Texas for generations. Farmers and ranchers, they had helped to tame the state and had fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. Lyndon's father had the gregarious gifts of a politician, and three years before Lyndon's birth, at the age of twenty-seven, he began serving as a Texas state representative. The elder Johnson, however, was less fortunate as a farmer and businessman. During Lyndon's early teenage years, his father piled up enormous debts, lost the family farm, and spiraled into financial crisis that rarely relented the rest of his life. The experience affected Lyndon throughout his own life and likely contributed to his commitment to improving the lot of the poor.

He did badly in school and was refused admission to college. After a brief period of doing odd jobs and getting into trouble, Johnson managed to enter Southwest Texas State Teachers College in 1927. He taught briefly, with a stint at a poor school in Cotulla, Texas, but his political ambitions had already taken shape. In 1931, he won an appointment as an aide to a congressman and left the teaching profession. The experience was electrifying: he had found his natural environment. He would not return to Texas full-time until 1969.

In 1934, he met Claudia Alta Taylor, "Lady Bird," and the two were married three months later. She was a perfect balance for him: charming and refined where he was raw and boisterous. She also had family money, which the Johnsons would eventually use to build a broadcasting and real estate empire.

Fast Political Track

In 1937, Johnson resigned as the state director of the National Youth Administration and won election to Congress, representing his home district as an ally of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was just twenty-eight years old.

He was an activist congressman, bringing electricity and other improvements to his district, but in 1941, he lost his first bid for the U.S. Senate, being defeated in an expensive and controversial election by W. Lee "Pass the Biscuits, Pappy" O'Daniel. Johnson remained in the House, and after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt helped him win a commission in the Naval Reserve.

On a tour of the southern Pacific, he flew one combat mission, and it provided an ironic moment in presidential history. Before takeoff, he left one B-26 bomber, the Wabash Cannonball, to use the restroom and on his return, boarded another plane, the Heckling Hare. During the bombing mission, the Heckling Hare was forced to run back to base, while the Wabash Cannonball crashed into the sea, killing all on board. Johnson received the prestigious Silver Star for his participation. Later, when President Roosevelt insisted that members of Congress leave active service, Johnson returned to his duties in Washington. In 1948, he was finally elected to the Senate by winning the controversial Democratic primary by 87 votes. Embittered by alleged instances of voter fraud, his opponents thereafter derisively referred to him as "Landslide Lyndon."Once in the Senate, Johnson advanced rapidly. Within two years, he was the Democratic whip; then, when the Republicans won a majority in the Senate on President Eisenhower's coattails, he became minority leader. In 1955, he was elected majority leader and transformed the position into one of the most powerful posts in American government. He worked ceaselessly and is perhaps best known for passage of the watered-down Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first such measure in almost a century. He also pushed for America's entry into what would become known as the Space Race. By 1960—after two failed attempts at the vice presidential nomination—he set his sights on the White House.

JFK and LBJ

That year, however, belonged to John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Young, handsome, rich, and witty, the Senator from Massachusetts piled up one primary win after another. Despite Johnson's announcement of his own candidacy, Kennedy was nominated on the first ballot at the Democratic convention in Los Angeles. Facing a seasoned Republican contender in Vice President Richard Nixon, Kennedy turned to Johnson to bring political and geographical balance to the ticket. Johnson delivered the South—including several states that had voted Republican during the Eisenhower years—and the team of JFK and LBJ won the election by the smallest popular margin of the century.

Although Johnson never seemed comfortable in the vice presidency, he headed the space program, oversaw a nuclear test ban treaty, and worked toward equal opportunity for members of racial minorities. He also publicly supported the young President's decision to send American military advisers to the Southeast Asian country of Vietnam, whose corrupt but friendly government was threatened by a Communist insurgency. Johnson was not, however, in Kennedy's inner circle and seemed frustrated by his lack of influence, particularly on legislative matters.

Legislative and World Impact

Johnson was only two cars behind Kennedy on the day the President was shot to death in Dallas. He was sworn in as President aboard Air Force One later that afternoon. A few days later, he spoke to a joint session of Congress. Seizing on Kennedy's inaugural plea to "let us begin anew," he asked Congress to "let us continue." Over the next year, he endorsed the late President's programs even as he announced his own. He pushed for passage of Kennedy's tax cut and civil rights bill and declared a "War on Poverty." When he ran for election against the Republican conservative Barry Goldwater in late 1964, he won by the biggest popular vote margin in history. During his presidency, Johnson engineered the passage of the Medicare program, poured money into education and reconstruction of the cities, and pushed through three civil rights bills that outlawed discrimination against minorities in the areas of accommodations in interstate commerce, voting, and housing.

But in the meantime, the conflict in Vietnam was intensifying. By 1965, the American "advisers" were a thing of the past as Johnson began an escalation of American commitment to more than 100,000 combat troops. Within three years, the number would swell to more than 500,000. As American casualties increased, an antiwar movement gathered momentum. The North Vietnamese and the National Liberation Front kept winning, even as Johnson poured more money, firepower, and men into the war effort. Ultimately, the President came to be identified personally with a war that seemed unwinnable. As a result, his popularity sagged drastically, dipping below 30 percent in approval ratings. Senator Eugene McCarthy, a Minnesota Democrat, announced that he would seek the Democratic nomination and did surprisingly well in the New Hampshire primary. President Kennedy's younger brother Robert also joined the race. On March 31, 1968, Johnson announced that he would neither seek nor accept the nomination. After a relatively short period in restless retirement, Lyndon Johnson died on January 22, 1973. His grave lies in a stand of live oaks along the Pedernales River at the LBJ Ranch.

Lyndon Baines Johnson was pure Texan. His family included some of the earliest settlers of the Lone Star State. They had been cattlemen, cotton farmers, and soldiers for the Confederacy. Lyndon was born in 1908 to Sam and Rebekah Baines Johnson, the first of their five children. His mother was reserved and genteel while his father was a talker and a dreamer, a man cut out for more than farming. Sam Johnson won election to the Texas legislature when he was twenty-seven. He served five terms before he switched careers and failed to make a living solely as a farmer on the family land seventy miles west of Austin.

Education and Teaching Career

In 1913, the Johnsons abandoned the farm and moved to nearby Johnson City. The family house, while comfortable by the standards of the rural South at the time, had neither electricity nor indoor plumbing. Lyndon, like his father, wanted more for his future. In fact, when he was twelve, he told classmates, "You know, someday I'm going to be president of the United States." Later in life, Johnson would remember: "When I was fourteen years old I decided I was not going to be the victim of a system which would allow the price of a commodity like cotton to drop from forty cents to six cents and destroy the homes of people like my own family." The climb out of the Texas Hill Country, however, would be a steep one. School, at first, was a one-room, one-teacher enterprise. Johnson City High School was a three-mile mule ride away from home. Lyndon graduated in 1924, president of his six-member senior class.

Sam Johnson's financial troubles took a toll on his health and his family. The Johnsons scrimped to send Lyndon to summer courses at Southwest Texas State Teachers College to supplement his meager rural education. But the boy did not do well, and he was not allowed into the college after finishing high school. This led to a "lost" period in Lyndon's life, during which he drifted about. With five friends, he bought a car and drove to California, where he did odd jobs and briefly worked in a cousin's law office. Lyndon then hitchhiked back to Texas and performed manual labor on a road crew. He fell into fights and drinking that eventually led to his arrest. In 1927, he refocused his energies on a teaching career and was accepted to Southwest Texas State Teachers College.

Johnson was an indifferent student, but he eagerly pursued extracurricular activities such as journalism, student government, and debating. He excelled in his student teaching and was assigned to a tiny Hispanic school in a deeply impoverished area. Johnson literally took over the school in Cotulla, pushing the long-neglected students and giving them a shred of hope and pride in their achievements. He earned glowing references. When Johnson graduated in 1930, however, America was just entering the Great Depression. His first teaching job paid $1,530—for the year. Johnson again did an exemplary job, but the unpaid political work he had been doing in his free time had fueled other ambitions. Not surprisingly, his teaching career was brief.

Tirelessly, he helped a political friend of his father in some local campaigns, and by late 1931, he had won a job as an aide to U.S. Congressman Richard Kleberg of Corpus Christi. In Washington, Johnson's work ethic was astounding. He poured over every detail of congressional protocol. No mail from Kleberg's constituents went unanswered. He was, in short, a model assistant. His drive, ambition, and competence made him stand out among the young people in Washington at that time. When he returned to Texas in 1934 to visit family, he met a twenty-one-year-old woman named Claudia Alta Taylor, a recent University of Texas graduate and a member of a wealthy East Texas family. They married three months later.

Marriage and Congressional Career

As a baby, Claudia's nanny had described her as "pretty as a lady bird," and the nickname stuck. Deeply shy but genuine and charming, Lady Bird became a refining balance to her boisterous, hyperactive husband and was a gracious hostess to Johnson's powerful new friends. The new President, Franklin Roosevelt, was fighting the Depression with dozens of social programs. Johnson, with the support of future Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, won appointment as Texas director of the National Youth Administration, a federal youth-employment program. Again, his work was superb, and when James Buchanan, the congressman in his home district, died in 1937, Johnson quickly moved to grab the job. He tapped his new wife's inheritance and her increasing assets as owner of a local radio station, aligned himself with Roosevelt's sweeping social policies, and won election in Texas's Tenth District. He was just twenty-eight years old.

Because of his age and ambition for even higher office, Johnson's early congressional record produced few results. By the late 1930s, however, he was winning federal housing projects and dams for his district. He managed to bring electrical power to the lonely Texas Hill Country of his youth, something he claimed for the rest of his days as his proudest achievement. When one of Texas's two U.S. senators died in 1941, Johnson seemed certain to inherit the job, but a conservative former radio star-turned-governor named W. Lee "Pass the Biscuits, Pappy" O'Daniel entered the race late. It was widely alleged that both candidates used fraudulent votes, but O'Daniel finagled more than Johnson and carried the election.

Still a member of the House, Johnson used his contacts with Roosevelt to obtain an officer's commission in the Naval Reserve. When the U.S. entered World War II, Johnson was appointed congressional inspector of the war's progress in the Pacific, thus maintaining his seat in the House. He went on a single bombing mission, securing the "combat record" and a Silver Star for serving under hostile fire. Observing wartime industrial and technological trends, Johnson invested and became well-to-do for the first time. Lady Bird, meanwhile, gave birth to two daughters, one born in 1944 and another three years later.

By the time the war ended, the world was a very different place—and so was America. Its uneasy ally from the war, the Soviet Union, refused to withdraw its armed forces from Europe. The Cold War had begun. Many of Johnson's countrymen were weary of the New Deal's activist social policies at home and the threat of more war overseas; the new communist expansion abroad frightened them. The Democrats were losing their longtime grip on Congress and the White House. While Johnson easily won a sixth term in 1948, his opponent painted him as an old-style liberal, a career politician who had profited from the war while exposing himself to little risk. The charges lingered into the following year, when Johnson tried once again to enter the U.S. Senate.

Yet again a popular Texas governor was in the way. His name was Coke Stevenson, and his presence and character were so impressive that he was widely known as "Mr. Texas." Johnson and Stevenson battled endlessly for the Democratic nomination and forced a runoff. The young congressman then waged an all-out, rough-and-tumble Lone Star State campaign and showed that he had learned lessons since his earlier Senate defeat. Three counties in the southern portion of the state provided highly suspicious vote tallies that gave Johnson the victory in the Democratic primary—crucial in those days to a general election, since Republicans were few and far between and could never win the subsequent election—by 87 votes out of a 250,000 cast. He easily defeated his Republican opponent in the general election and won the Senate seat, but the cost to his credibility was steep. Everyone knew the election had been rife with fraud, and his slim, questionable margin of victory was certainly no popular mandate. Critics began calling him "Landslide Lyndon," and the new senator found their disdain hard to shake for a long time.

Senator par Excellence

As a senator, Johnson found his true calling. The Senate, with only a quarter of the membership of the House, gave him a higher national profile. Johnson's ascent to power was startling; by the end of his first term, he was one of the most powerful senators in America. He used strategies that had enabled his fast climb in the House: wooing powerful members, angling for spots on important committees, and outworking everyone. Because both Senate Democratic leaders had been defeated by the resurgent Republicans in the recent election, it was a time of rapid advancement for newcomers. Just two years into his Senate term, Johnson was named the whip, or assistant to his party's leader, in charge of rounding up votes. Two years after that, Republicans won a majority in the Senate on the coattails of the new President, Dwight Eisenhower. Once again, Johnson's Democratic superiors were election casualties, so he became minority leader. In the fall 1954 elections, the Democrats had regained control of the Senate, and when the Senate convened in 1955, Johnson became majority leader. It was a dizzyingly fast climb.

Early in LBJ's Senate career, he had championed military preparedness, but as he rose to power, he increasingly turned his attention to domestic issues. Already contemplating a White House run of his own, he strategically sought to work with, not against, the popular Eisenhower. Laboring almost around the clock, begging and berating to get his way, Johnson was the Senate's master, perhaps its most powerful leader ever. Working with fellow Texan and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, Johnson was able to compile an impressive record of legislative achievement. LBJ did his homework and had an uncanny ability to know how to approach other senators. He became known for the "Johnson Treatment," in which he leaned close in on a senator, towering over his prey, speaking softly and cajoling, flattering, even bribing, until he won the senator's vote.

Unfortunately, his drive and ambition almost killed him. In mid-1955, he suffered a massive heart attack in the bucolic Virginia countryside. Not yet fifty, he reassessed his life; he quit smoking, lost weight, and tried to delegate more of his work. He was instrumental in winning passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, working closely with Eisenhower while soothing southern colleagues who were suspicious of such social change. When the Soviets launched Sputnik, the world's first satellite that year, he led the way to get America into the race for space. By 1958, Johnson sensed that he had gone as far in the Senate as he ever would. He turned his sights on the prize of prizes: the presidency.

A Heartbeat from the Presidency

Being from the South was still a handicap to a presidential candidate in 1960; the region had not yet assumed the kind of power that would put Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton in the White House in later years. In 1952 and 1956, Johnson had tried but failed to be named vice president on the Democratic ticket, referring to himself as a "western" candidate. In 1960, his primary foe for the nomination was his Senate colleague, John Fitzgerald Kennedy of Massachusetts. For the only time in his life, Johnson was out-campaigned. Kennedy announced his candidacy early, spent lavishly, worked local political machines with corporate efficiency, and piled up one primary win after another. Johnson held back, waiting for Kennedy's youth and Catholicism to take its toll. It never did. The young man from Boston won the party's nomination on the first ballot.

However, Kennedy was a decided underdog to win the White House. The Republicans had nominated a skilled and compelling candidate, Vice President Richard Nixon. The Democrats needed a running mate who would appeal to those that JFK made uneasy. Lyndon Johnson—southern, Protestant, mature, and the ultimate congressional insider—would be a perfect contrast to the northeastern, Catholic, youthful Democratic nominee. Kennedy was both amused and awed by the larger-than-life Texan and was mildly surprised when Johnson not only accepted the offer but campaigned hard for the ticket. It paid off because 1960 was the closest presidential race of the century. Several southern states that had defected to the Republicans during the Eisenhower years returned to the Democratic fold and helped Kennedy win. (See Kennedy biography, Campaigns and Elections section, for details.)Kennedy relegated Johnson to the outer circles of the New Frontier but did give him some significant responsibilities. Johnson headed the space program, played a key role in military policy, and chaired the President's Committee for Equal Employment Opportunity. In foreign policy, Johnson had much less influence, though he did encourage acceptance of a diplomatic "trade" of Russian missiles in Cuba for American ones in Turkey. Kennedy typically did not rely on LBJ for advice in these matters, however. Overall, Johnson was frustrated as vice president, particularly when the New Frontiersmen around Kennedy ignored him and refused to take advantage of his expertise.

In late November 1963, Kennedy decided to travel to Texas to shore up support for his upcoming reelection bid. Johnson was riding two cars behind Kennedy's in the motorcade when the bullets struck the young President. By the time Johnson reached the hospital, Kennedy was dead. Aboard Air Force One, before its return to Washington, Johnson was sworn in as President; Lady Bird and Kennedy's widow were at his side. When the plane landed, he gave a brief speech to his dazed nation, promising, "I will do my best—that is all I can do." Two weeks later, Johnson moved into the White House. One adviser never forgot the image of a mover packing Kennedy's trademark rocking chair—while another carried in Johnson's cowboy saddle."All that I have I would have given gladly not to be standing here today," Johnson told a joint session of Congress when he outlined his plans for governing. He kept Kennedy's cabinet and top aides, telling them that he and the nation needed them to provide continuity. Within days, Johnson firmly grasped the reins of government. His grief at Kennedy's tragedy was balanced by the demands and responsibilities of the Oval Office.

The Campaign and Election of 1964

Lyndon Johnson's nomination for the top spot on the Democratic ticket in 1964 was a foregone conclusion, with his glittering legislative success and stellar approval ratings. At his party's convention, he introduced his running mate, Hubert H. Humphrey, a liberal senator from Minnesota who gave the ticket geographic and ideological balance.

In sharp contrast, the Republicans were torn by the intense divisions between its old-guard, eastern, moderate base and the upstart, conservative insurgents from the South and West. Barry Goldwater, a deeply conservative senator from Arizona, took the nomination after a hotly contested fight. Senator Goldwater promised to reorient the party rightward, offering "a choice, not an echo" for conservatives. In his nomination speech, he appealed to conservative "purists" and threw down the gauntlet to Republican moderates with the famous words "Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice."By rejecting any unity gestures toward Republican moderates, Goldwater alienated much of the party; only one-fifth of its voters was comfortable with his nomination. Goldwater's slogan, "In your heart, you know he's right," seemed to imply that liking him was something to be ashamed of: Democratic wags countered, "In your guts, you know he's nuts." Goldwater's television advertising was outdated and inept while Johnson's, on the other hand, was state of the art. One little-shown Johnson campaign spot has proven to be one of the most memorable political ads ever. It featured a little girl in a meadow, playfully pulling the petals off a daisy, counting down from ten to zero until she is blotted out by a nuclear explosion. Johnson, meanwhile, portrayed himself as a moderate and a peacemaker.

When all the votes were tallied, most Democratic voters remained with their party, and large numbers of Republicans joined independent voters in the Democratic column. Johnson reveled in this "frontlash" that counteracted the white "backlash" caused by his support of the Civil Rights Act. Only in the Deep South did Goldwater win over large numbers of Democrats, and that was by virtue of his opposition to Johnson's integrationist agenda. Johnson won by the widest margin of popular votes in American history. Additionally, he enjoyed a huge 10 to 1 victory in the electoral college. For Republicans, it was an electoral disaster of monumental proportions. For Johnson and the Democrats, the election gave them an opportunity that they had not enjoyed since the early days of the New Deal: the opportunity to pass a comprehensive liberal program.

President Joe Biden’s decision to step aside as the Democratic Party’s 2024 presidential nominee inevitably leads to comparisons with Lyndon Johnson’s withdrawal from the party’s 1968 nomination contest. The analogy is not perfect: Johnson made his announcement in March, not July; he had not yet secured the nomination, although he was the party’s likely candidate; in 1968, the nomination process relied on party officials, rather than delegates chosen by primary voters; Johnson’s withdrawal had little to do with his age, although health may have been a background concern; Johnson’s action also preceded, rather than followed, attacks by assassins on other candidates and leaders.

Finally, open opposition to LBJ’s nomination had emerged within the party, in the form of challenges first by Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota and then – following McCarthy’s stronger than expected showing in the New Hampshire primary – by Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York. As the brother of the slain president and as Lyndon Johnson’s most bitter rival, Kennedy presented a potentially formidable threat.

Such differences aside, though, Johnson’s 1968 decision is one of only two cases in U.S. history that we have available for comparison (President Harry Truman in 1952 is the other). As such, exploring Johnson’s reasons for leaving the race can help us grasp the gravity of such a decision, as well as the cross-cutting pressures that might motivate a president to end his career voluntarily. The secret White House Recordings provide a rich source of insight into such questions, helping us go beyond easy assumptions that division over Vietnam or fears about his political prospects forced LBJ’s hand.

What the tapes reveal is that while Johnson feared that Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s insurgent campaign might gain momentum, he had received recent reassurances that most key party officials remained loyal and that his prospects for winning the nomination were strong. In the days leading up to his March 31 announcement that he would leave the race, however, frustration over the stagnation of his domestic agenda drove Johnson’s decision process.

A Miller Center exhibit from 2018 captures the full set of recorded conversations that bear on LBJ’s withdrawal: Four key conversations, though, capture the critical moments in the process. A final conversation captures a human element among these momentous events.

On March 22, in a call with Senator Richard Russell [D-Georgia], President Johnson expressed concern about the momentum that Senator Robert F. Kennedy had generated since declaring his candidacy on March 16:

President Johnson: Now, [Robert F.] Bobby [Kennedy] [D–New York] is storming these states and these governors and switching them and switching the bosses all over the country, and a pretty blitz, ruthless operation. "If you don't do this, I'll defeat you." And he's doing it with candidates for the Senate and things of that kind . . . . there's been a great shift of sentiment, unless I'm misinformed, from what I see in the wires and the letters. Just nearly everybody since he got in and started speaking to these student groups around the country, just thinks we've played hell and we ought to get out right quick. It's the worst thing I've ever seen.

Russell: [Coughs.] Well, I . . . I don't think everybody does by a whole lot.

President Johnson: No. No, but I think there's been a good shift of sentiment is what I'm saying.

Johnson’s mood, however, was far from constant. Just a day later, he suddenly seemed confident about his prospects against Kennedy in a conversation with Chicago Mayor Richard Daley:

President Johnson: You and [New Jersey Governor Richard J.] Dick Hughes and Pennsylvania and Texas, and I don't think we'll lose a single mountain state or a single southern state. And I think that—I counted the congressmen last night. We have 160 and he has 8, [Daley acknowledges] and they're from Massachusetts and New York, and most of them are real extreme reform left-wingers . . . . what we've got to do is this: we've got to have four men kind of be my board of directors, run this country. We got to get you and Dick Hughes of New Jersey, who is just as solid as a rock. We've got to get [Mayor Joseph M. "Joe"] Barr and [Mayor James H. J.] Tate of Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. We were there yesterday, and they're just as solid as a rock. And if we can take—we've got Ohio at the moment; he's trying to buy it off, but we—if we can take Ohio and Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Texas, and New Jersey—

Daley: Hell, we're in.

President Johnson: —well, that's all of it, that's all of it.

Daley: I think it'll be a landslide.

"I'm not master of a damn thing"

By March 24, President Johnson’s confidence had faded. Faced with looming budget shortfalls, driven by spending for the war and the Great Society, LBJ felt that he had to secure a 10 percent federal income tax surcharge. Conservatives in Congress, though, refused to support the tax increase unless Johnson agreed to cut domestic spending. Doing so, however, would ignite a rebellion from liberal Democrats (including Kennedy) who were calling from dramatic increases in spending on the cities. In a conversation with Secretary of the Treasury Henry H. "Joe" Fowler, LBJ expressed his growing sense of political weakness.

Fowler: Well, you hear, of course, from this constituency. And I know it's there. I know the concern about it. Of course, the constituency I hear from is just all the other way. And [Richard M. "Dick"] Nixon is preparing a blast for a speech on fiscal responsibility to tear the hide off.7 He's going to make a major issue of it.

President Johnson: I think that's right. I sure think he's there. [Fowler attempts to interject.] And I think that it's right with the Congress. It's not because we haven't—we can't make them do it. We've been abandoned.

Fowler: Well, you see, however, the—as I've told you, the trap that—the plan that Williams has made is to point out that you've got two-thirds of the Senate. You are the master of the Senate and always have been.

President Johnson: That's not—I'm not master of a damn thing. I haven't got anybody—

. . . .

President Johnson: These 32 [senators] that you're talking about, and when you add 22 more with them, which you're likely to, they'll just murder us. They'll say we took the baby's milk. We took these things. I don't mind cutting space and supersonics and stuff like that, but when you go to moving into this poverty area, they're already screwing me. They just murder me every day.

Shortly later, a call with House Ways and Means Committee chairman Wilbur D. Mills of Arkansas about the tax surcharge bill further deepened the President’s despair about his ability to advance a policy agenda—and to maintain the political support necessary for a campaign:

President Johnson: If you can't—if you don't think the country's going to hell, why, then, maybe it's not. Maybe I'm wrong. But I think it is. I think we're in the most dangerous thing I ever saw in my life, and I think it's going to blow right in our face and ruin all of us. And all of us go down together. And I may go down anyway, but all of us on this. I really honestly think that, and I don't think that I can take the lead in wrecking my programs. I just don't believe I can. I just don't believe I'll have any support. I don't think the southerners like me to begin with. I know damn well the Republicans are not going to like me. And if I run off all the regular Democrats, I'm in a hell of a shape. And I know what [Richard J.] Dick Hughes will do, and I know what [Richard J.] Dick Daley will do, and I know what Ohio and Pennsylvania and [Joseph M.] Joe Barr, head of the Mayors' Conference in Pittsburgh, will do.11 And if I just go out here and say I'm going to do it, I know what Meany will do. And that's about all the support I got left. And I sure as hell don't want to make you mad, and I . . . you and [Mike] Mansfield [D-Montana] and [Carl B.] Albert [D–Oklahoma] are kind of my leaders. And hell, if I ain't got you, I ain't got any leaders. I'm just a coach without any halfbacks out there on the field. I just tell them, "Go run play 29," but there ain't a damn human to pick it up. So, I can't win a game under those circumstances. Now, tell me what the hell to do.

Mills only advice was to wait a few weeks in the hope that the situation would improve.

President Johnson did not record another call until the night of March 31, after he had stunned the nation with his announcement that "I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president."

The conversations highlighted here demonstrate that Johnson left the race not just because of Vietnam or the challenge posed by Robert F. Kennedy, but also because of his inability to make progress on his domestic agenda. The tax surcharge bill represented the broader problem that fiscal woes brought on by the war had placed the expansion, or possibly even the continuation of the Great Society impossible. That agenda lay at the heart of Lyndon Johnson’s motivation to seek the power of the presidency. Deprived of the ability to advance it, he had little reason to continue.

"Our friendship was never severed"

Following the televised statement, President Johnson received a call from Abigail McCarthy, the wife of Sen. Eugene J. "Gene" McCarthy [DFL–Minnesota] whose surprisingly strong showing in the New Hampshire primary had spurred Kennedy into the race and raised doubts about Johnson’s candidacy. Shocked in the aftermath of the President’s statement, Abigail McCarthy wanted to talk not about politics, but about reconnecting to Johnson in a way that went beyond politics:

Abigail Q. McCarthy: Mr. President?

President Johnson: Yes.

McCarthy: This is Abigail McCarthy.

President Johnson: Oh, Abigail, how are you?

McCarthy: I am fine, Mr. President, but I am overcome with emotion, really. I don't see how you could have done this.

President Johnson: [speaking softly] Well, I just thought we had to do it because there's so much at stake that one little person like me doesn't—

McCarthy: You know you aren't one little person, Mr. President.

President Johnson: [Slight chuckle.] Well, I've got nine months now to do nothing except—I won't spend one moment doing anything except trying to find peace, and I thought that I—it was—I just thought I had to do it.

McCarthy: Well, I just want to tell you, you have my affection and respect, and I want you to tell Lady Bird [Johnson] how much I love her.

President Johnson: I sure will, dear, and I think it's awfully nice of you to call.

McCarthy: Well, I'm just—you know, I can hardly talk.

President Johnson: Well . . .

McCarthy: I mean, I remember another time like this with Mr. [Harry S.] Truman. And, Mr. President, really, that was—you know, it—it's just shocked us to our feet here, you know?

President Johnson: Everything—everything will be better, and we'll have a lot of time to devote to what's really important. And after 37 years, you learn what is important. And the—I've just—I—

McCarthy: You know, Mr. President—you know, basically our friendship was never severed.

President Johnson: I hope not. I hope not.

McCarthy: Yes.

President Johnson: I don't want it to be.

Although initiated by Abigail McCarthy, this final call represented a tentative rapprochement between intra-party rivals. It will be interesting to learn, in future memoirs and oral histories, whether Joe Biden has begun such a process of reconciliation with those called on him to step aside in the summer of 2024.

Learn more about Lyndon B. Johnson or listen to our collection of tapes.

The Lyndon Johnson presidency marked a vast expansion in the role of the national government in domestic affairs. Johnson laid out his vision of that role in a commencement speech at the University of Michigan on May 22, 1964. He called on the nation to move not only toward "the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society," which he defined as one that would "end poverty and racial injustice." To that end, the national government would have to set policies, establish "floors" of minimum commitments for state governments to meet, and provide additional funding to meet these goals. By winning the election of 1964 in a historic landslide victory, LBJ proved to America that he had not merely inherited the White House but that he had earned it. The election's mandate provided the justification for Johnson's extensive plans to remake America. Large Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, along with Johnson's ability to deal with powerful, conservative southern committee leaders, created a promising legislative environment for the new chief executive.

The Great Society

Johnson labeled his ambitious domestic agenda "The Great Society." The most dramatic parts of his program concerned bringing aid to underprivileged Americans, regulating natural resources, and protecting American consumers. There were environmental protection laws, landmark land conservation measures, the profoundly influential Immigration Act, bills establishing a National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, a Highway Safety Act, the Public Broadcasting Act, and a bill to provide consumers with some protection against shoddy goods and dangerous products.

To address issues of inequality in education, vast amounts of money were poured into colleges to fund certain students and projects and into federal aid for elementary and secondary education, especially to provide remedial services for poorer districts, a program that no President had been able to pass because of the disputes over aid to parochial schools. Johnson, a Protestant, managed to forge a compromise that did provide some federal funds to Catholic parochial schools. He signed the bill at the one-room schoolhouse that he had attended as a child near Stonewall, Texas. With him was Mrs. Kate Deadrich Loney, the teacher of the school in whose lap Johnson sat as a four-year-old.

To deal with escalating problems in urban areas, Johnson won passage of a bill establishing a Department of Housing and Urban Development and appointed Robert Weaver, the first African American in the cabinet, to head it. The department would coordinate vastly expanded slum clearance, public housing programs, and economic redevelopment within inner cities. LBJ also pushed through a "highway beautification" act in which Lady Bird had taken an interest. For the elderly, Johnson won passage of Medicare, a program providing federal funding of many health care expenses for senior citizens. The "medically indigent" of any age who could not afford access to health care would be covered under a related "Medicaid" program funded in part by the national government and run by states under their welfare programs.

The War on Poverty

LBJ's call on the nation to wage a war on poverty arose from the ongoing concern that America had not done enough to provide socioeconomic opportunities for the underclass. Statistics revealed that although the proportion of the population below the "poverty line" had dropped from 33 to 23 percent between 1947 and 1956, this rate of decline had not continued; between 1956 and 1962, it had dropped only another 2 percent. Additionally, during the Kennedy years, the actual number of families in poverty had risen. Most ominous of all, the number of children on welfare, which had increased from 1.6 million in 1950 to 2.4 million in 1960, was still going up. Part of the problem involved racial disparities: the unemployment rate among black youth approached 25 percent—less at that time than the rate for white youths—though it had been only 8 percent twenty years before.

To remedy this situation, President Kennedy commissioned a domestic program to alleviate the struggles of the poor. Assuming the presidency when Kennedy was assassinated, Johnson decided to continue the effort after he returned from the tragedy in Dallas. One of the most controversial parts of Johnson's domestic program involved this War on Poverty.

Within six months, the Johnson task forces had come up with plans for a "community action program" that would establish an agency—known as a "community action agency" or CAA—in each city and county to coordinate all federal and state programs designed to help the poor. Each CAA was required to have "maximum feasible participation" from residents of the communities being served. The CAAs in turn would supervise agencies providing social services, mental health services, health services, employment services, and so on. In 1964, Congress passed the Economic Opportunity Act, establishing the Office of Economic Opportunity to run this program. Republicans voted in opposition, claiming that the measure would create an administrative nightmare, and that Democrats had not been willing to compromise with them. Thus the War on Poverty began on a sour, partisan note.

Soon, some of the local CAAs established under the law became embroiled in controversy. Local community activists wanted to control the agencies and fought against established city and county politicians intent on dominating the boards. Since both groups were important constituencies in the Democratic Party, the "war" over the War on Poverty threatened party stability. President Johnson ordered Vice President Hubert Humphrey to mediate between community groups and "city halls," but the damage was already done. Democrats were sharply divided, with liberals calling for a greater financial commitment—Johnson was spending about $1 billion annually—and conservatives calling for more control by established politicians. Meanwhile, Republicans were charging that local CAAs were run by "poverty hustlers" more intent on lining their own pockets than on alleviating the conditions of the poor.

By 1967, Congress had given local governments the option to take over the CAAs, which significantly discouraged tendencies toward radicalism within the Community Action Program. By the end of the Johnson presidency, more than 1,000 CAAs were in operation, and the number remained relatively constant into the twenty-first century, although their funding and administrative structures were dramatically altered—they largely became limited vehicles for social service delivery. Nevertheless, other War on Poverty initiatives have fared better. These include the Head Start program of early education for poor children; the Legal Services Corporation, providing legal aid to poor families; and various health care programs run out of neighborhood clinics and hospitals.

Overall government funding devoted to the poor increased greatly. Between 1965 and 1968, expenditures targeted at the poor doubled, from $6 billion to $12 billion, and then doubled again to $24.5 billion by 1974. The billions of dollars spent to aid the poor did have effective results, especially in job training and job placement programs. Partly as a result of these initiatives—and also due to a booming economy—the rate of poverty in America declined significantly during the Johnson years. Millions of Americans raised themselves above the "poverty line," and the percentage under it declined from 20 to 12 percent between 1964 and 1974. Nevertheless, the controversy surrounding the War on Poverty hurt the Democrats, contributing to their defeat in 1968 and engendering deep antagonism from racial, fiscal, and cultural conservatives.

Civil Rights and Race Relations

Johnson was from the South and had grown up under the system of "Jim Crow" in which whites and blacks were segregated in all public facilities: schools, hotels and restaurants, parks and swimming pools, hospitals, and so on. Yet even as a senator, he had become a moderate on race issues and was part of efforts to guarantee civil rights to African Americans. When Johnson assumed the presidency, he was heir to the commitment of the Kennedy administration to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ending segregation in public facilities. As a result of his personal leadership and lobbying with key senators, he forged a bipartisan coalition of northern and border-state Democrats and moderate Republicans. These senators offset a coalition of southern Democrats and right-wing Republicans, and a bill was passed. It made segregation by race illegal in public accommodations involved in interstate commerce—in practice this would cover all but the most local neighborhood establishments.

The following year, civil rights activists turned to another issue: the denial of voting rights in the South. Since the 1890s, blacks had been denied access to voting booths by state laws that were administered in a racially discriminatory manner by local voting registrars. These included (1) literacy tests which could be manipulated so that literate blacks would fail; (2) "good character" tests which required existing voters to vouch for new registrants and which meant, in practice, that no white would ever vouch for a black applicant; and (3) the "poll tax" which discriminated against poor people of any race. The poll tax was eliminated by constitutional amendment, which left the literacy test as the major barrier. In 1965, black demonstrators in Selma, Alabama, marching for voting rights were attacked by police dogs and beaten bloody in scenes that appeared on national television.

In response to public revulsion, Johnson seized the opportunity to propose the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This piece of legislation provided for a suspension of literacy tests in counties where voting rates were below a certain threshold, which in practice covered most of the South. It also provided for federal registrars and marshals to enroll African American voters. The law was passed by Congress, and the results were immediate and significant. Black voter turnout tripled within four years, coming very close to white turnouts throughout the South. Blacks entered the previously "lily white" Democratic Party, forging a biracial coalition with white moderates. Meanwhile, white conservatives tended to leave the Democratic Party, due to their opposition to Johnson's civil rights legislation and liberal programs. Many of these former Democrats joined the Republican Party that had been revitalized by Goldwater's campaign of 1964. The result was the development of a vibrant two-party system in southern states—something that had not existed since the 1850s.

Even with these measures, racial tensions increased. In addition, the civil rights measures championed by the President were seen as insufficient to minority Americans; to the majority, meanwhile, they posed a threat. Between 1964 and 1968, race riots shattered many American cities, with federal troops deployed in the Watts Riots in Los Angeles as well as in the Detroit and Washington, D.C., riots. In Memphis in the summer of 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., one of the leaders of the civil rights movement, was gunned down by a lone assassin. There were new civil disturbances in many cities, but some immediate good came from this tragedy: A bill outlawing racial discrimination in housing had been languishing in Congress, and King's murder renewed momentum for the measure. With Johnson determined to see it pass, Congress bowed to his will. The resulting law began to open up the suburbs to minority residents, though it would be several decades before segregated housing patterns would be noticeably dented.

Although the Great Society, the War on Poverty, and civil rights legislation all would have a measurable and appreciable benefit for the poor and for minorities, it is ironic that during the Johnson years civil disturbances seemed to be the main legacy of domestic affairs. Johnson appointed the Kerner Commission to inquire into the causes of this unrest, and the commission reported back that America had rapidly divided into two societies, "separate and unequal." It blamed inequality and racism for the riots that had swept American cities. Johnson rejected the findings of the commission and thought that they were too radical. By 1968, with his attention focused on foreign affairs, the President's efforts to fashion a Great Society had come to an end.

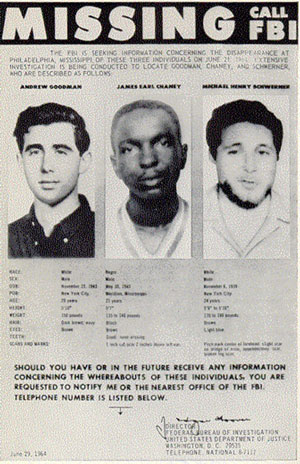

In the summer of 1964, the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) coordinated efforts to register African American voters in Mississippi as part of its three-year-old civil rights organization efforts. Beginning in June, the first contingent of Freedom Summer volunteers began arriving in Mississippi after training sessions in Oxford, Ohio. Approximately 250 activists made it to the Magnolia State between June 20 and June 22. One of them was Andrew Goodman, the son of a prominent Jewish family from Manhattan.

On June 21, 1964, two days after the Senate passage of the Civil Rights Act and two weeks before President Johnson signed that landmark piece of legislation, Andrew Goodman went with James Chaney and Michael Schwerner to investigate the burning of the Mt. Zion Church in the Longdale community in Neshoba County, near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Chaney and Schwerner were both veteran civil rights activists involved in political mobilization efforts, one an African American from Mississippi and the other a Jewish social worker from New York City whom some locals called "Goatee." While attempting to return to Meridian, Mississippi, the three men were arrested for traffic violations and jailed. After being released from jail at 10 p.m., they disappeared.

When they did not report in by phone as civil rights workers in Mississippi were trained to do, fellow activists began calling local and federal law-enforcement officials. Although many feared the worst, none of them knew for certain that a band of white supremacists associated with the Ku Klux Klan and the Neshoba County Sheriff’s Department had murdered them on a rural roadway.

Secret White House Tapes

Despite the existence of court records, news reports, oral histories, and documents relating to the investigation, the violent events of that summer will never be entirely clear, and students of history will continue to debate the ambiguities of evidence in attempting to understand that muggy, 80-degree Mississippi night. One resource, though, that captures the immediacy of their disappearance and the complications it presented for federal and state authorities—and for activists—is the collection of secret recordings made by President Lyndon Johnson.

President Johnson ramped up the investigation into the disappearances by prodding FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, by seeking advice from Cabinet officers and congressional leaders, and by involving the Defense Department (eventually bringing in hundreds of sailors to scour the countryside, particularly its swampy areas where it was presumed the bodies might have been hidden). The president received reports and held meetings throughout the day. Beginning around noon, he turned on his Dictabelt telephone recorders.

"This means murder"

President Johnson’s first recorded conversation on the matter was with Lee White, a holdover from the Kennedy administration who served as Johnson’s chief aide on civil rights matters. The two discussed how best to respond to James Farmer, the director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which was one of the chief groups involved in the COFO voter registration campaign and Freedom Summer.

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 12:35 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Lee White

Tape: WH6406.13

Conversation: 3818

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"What do you think happened to them?"

Over the next four hours, the president spoke to the Speaker of the House (twice) and the secretary of commerce—Southerner Luther Hodges—about the complications of using extensive federal force in the South. He also made several calls regarding campaign issues and received a message from Attorney General Robert Kennedy. At 3:35 p.m., Johnson tried to return Kennedy’s call, but he spoke instead to Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. This snippet is part of a nine-minute call.

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 3:35 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Nicholas Katzenbach

Tape: WH6406.13

Conversation: 3832

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"We got three kids missing"

Just before 4 p.m., the president made contact with arch-segregationist James Eastland, a colleague from Johnson’s Senate days who was a virulent opponent of the civil rights movement. In the call, Eastland, in his thick Mississippi Delta accent, mocked the idea that any violence had occurred and gave voice to a prevalent white Southern belief that the disappearance was a “publicity stunt."

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 3:59 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, James Eastland

Tape: WH6406.14

Conversation: 3836

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"We found the car"

Almost immediately after his call with Eastland, the president received news from longtime FBI director J. Edgar Hoover that seemed to confirm the worst possible outcome. The Bureau had found the burned car of the activists, and Hoover expressed his assumption that “these men have been killed.”

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 4:05 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, J. Edgar Hoover

Tape: WH6406.14

Conversation: 3837, 3838

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"I'm here with the parents of these boys"

While the parents of Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were in the Oval Office with President Johnson, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara phoned twice. The second time, Johnson spoke specifically about Mississippi. The recording here begins with Johnson speaking about the families.

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 5:44 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara

Tape:WH6406.14

Conversation: 3855

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"The bodies were not in the car"

Along with calls from Senator Everett Dirksen about an Illinois navigation project, the news about the car dominated discussions until Hoover called back at 7:15 p.m. to report that no bodies were found in the car. Prior to Hoover’s call, Robert Kennedy had arrived at the White House to help plan the Justice Department’s involvement in the investigation and to lobby former CIA Director Allen Dulles to become an “impartial observer” of the situation in Mississippi for the administration.

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 7:15 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, J. Edgar Hoover

Tape: WH6406.15

Conversation: 3869

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"Likely that none of them were burned"

After hearing the news from Hoover, Johnson made personal calls to the parents of Schwerner and Goodman, but was unable to find the phone number for the family of Chaney. Johnson had received the numbers for the White parents—Schwerner and Goodman—from their congressmen, but had to rely on AT&T operators for Chaney’s number (a misspelling of Chaney's name kept them from finding it). Ten minutes before the call to Anne Schwerner, Johnson exchanged views with Mississippi Governor Paul Johnson, a successor to Ross Barnett and a man who in a previous campaign had referred to the NAACP as standing for “Niggers, Apes, Alligators, Coons, and Possums.” Johnson continued his phone calling for another two hours, speaking with the father of Andrew Goodman, to members of Congress, to Lee White, Allen Dulles, and, finally, to Secretary of State Dean Rusk (about the resignation of Henry Cabot Lodge as ambassador to South Vietnam).

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 8:35 p.m., 8:50 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon B. Johnson, Anne Schwerner, Robert Goodman, Lee C. White, White House Operators

Tape: WH6406.16

Conversation: 3882, 3884, 3887

Click to listen to the whole conversation with Anne Schwerner.

Click to listen to the whole conversation with Robert Goodman.

June 24 to August 3, 1964

Over the next week, Johnson continued to press for results in the investigation, while turning more of his attention to other matters of state, particularly the conference report on the Civil Rights Act. In a triumphal moment, he signed the bill on July 2. The bill’s victory was bittersweet for activists in Mississippi and the loved ones of the three missing men. Despite exploring hundreds of leads, the investigation had yielded scant evidence of the men’s location and had led to no arrests. A major break in the case occurred in early August, when an FBI informant (paid $30,000) pointed the Bureau to a farm pond just southwest of Philadelphia.

"The FBI has found three bodies"

Assistant Director of the FBI Cartha “Deke” DeLoach called Johnson to notify him that the bodies had been found. That day, Johnson was also coping with racial disorders in New Jersey as well as the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Date: August 4, 1964

Time: 8:01 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Cartha “Deke” DeLoach

Tape: WH6408.05

Conversation: 4693

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"Call the families"

Immediately following the conversation with Cartha DeLoach, Johnson called Lee White and asked him to give the families the news about the three bodies.

Date: August 04, 1964

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Lee White

Tape: WH6408.05

Conversation: 4694

Violence in Mississippi

Before the Freedom Summer students left Ohio, they had been briefed by John Doar, a representative from the U.S. Justice Department who informed them that the federal government could not provide them with protection in Mississippi. He emphasized that local and state officials held the responsibility for maintaining law and order, an ominous assurance given Mississippi's track record for not protecting civil rights workers.

In Mississippi and elsewhere in the South, civil rights activists complained bitterly about the lack of federal protection, and many believed that Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover was an enemy of the movement (and he certainly had many activists under FBI surveillance). A prominent feeling was that the FBI investigated white racial violence when pressed to do so, but those investigations often went little beyond intelligence gathering and thus served little deterrent value to would-be white terrorists.

At the time, the disappearance and presumed murder of these activists at the beginning of Freedom Summer captivated the nation and became a landmark moment in the history of the civil rights movement. The attention focused on Mississippi, however, did not stop violence against civil rights activists or black Mississippians. Over the course of Freedom Summer, three other bodies of murdered black men were found, each of them had been lynched: Charles Moore and Henry Dee were found in mid-July in a lake off of the Mississippi River; a young man wearing a CORE t-shirt, likely a teenager named Herbert Oarsby, was found in the Big Black River. There were also approximately 70 bombings or burnings, 80 beatings, and more than 1,000 arrests of activists. The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) incident report, a single-spaced document that offered brief daily summaries, was more than 10 pages long.

The FBI's case into the disappearance of the civil rights workers became part of their investigation into church burnings known as MIBURN or Mississippi Burning. A controversial Hollywood film of the same name was released in 1988 (Mississippi Burning; directed by Alan Parker). It stirred further interest in the case, but caused many civil rights activists to shudder in horror at the heroic presentation of the FBI and at the downplaying of black activism in the movement.

Exactly 41 years later, the state of Mississippi obtained its first homicide conviction in the case. On Tuesday June 21, 2005, nine white and three black jurors convicted 80-year-old Edgar Ray “Preacher” Killen of manslaughter for his role in orchestrating the nighttime roadside lynching, which transpired approximately a half-mile from his house. For his crime, Killen received the maximum sentence of 60 years.

Although this was the first state conviction, it was not the first in the case, as federal conspiracy charges had led to prison time for a few of the other men involved in the murders. In October 1967, in federal court, an all-white jury convicted seven white men, including Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price. Eight others, including Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence Rainey, were acquitted. The cases of three others—one of them involving Edgar Killen—ended in a mistrial. At the time, no one was brought to trial on state murder charges.

Killen’s 2005 trial has proved once again the epigram of Mississippi’s sage novelist William Faulkner that "the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” While the U.S. government is engaged in a struggle against terrorism worldwide, the Killen case offers a reminder of the realities of racial segregation and the use of terrorism at home to attempt to preserve white supremacy.

Learn more about Lyndon B. Johnson or listen to our collection of tapes.