Richard Nixon: Campaigns and Elections

Although it was a close race with respect to the popular vote, Nixon won the electoral college by a 3 to 2 margin

The Election of 1968:

Richard Nixon's presidential defeat in 1960 and gubernatorial defeat in 1962 gave him the reputation of a loser. He spent six years shaking it before he could win the 1968 Republican presidential nomination. During that time, he joined a prestigious law firm in New York City, became financially well off, and argued a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. Nixon played a marginal role in presidential politics in 1964, introducing his party's nominee at the GOP convention in San Francisco's Cow Palace: "He is the man who earned and proudly carries the title of Mr. Conservative. He is the man who, by the action of this convention, is now Mr. Republican. And he is the man who, after the greatest campaign in history, will be Mr. President—Barry Goldwater." Nixon campaigned for Goldwater and other Republicans that fall, earning the gratitude of conservatives, who together with their standard-bearer went down to defeat in the largest landslide in post-war history.

It looked like the end of conservatism, the triumph of liberalism. It was neither. Out of the wreckage of Goldwater's candidacy rose a charismatic conservative star, Ronald Wilson Reagan. On the strength of a single, nationally televised speech, Reagan took Goldwater's place as first in the hearts of the conservative movement, confronting Nixon with a formidable rival for the 1968 nomination. But Reagan had never held public office and had to run for governor of California before he could be a credible presidential candidate. He won the 1966 gubernatorial race in a landslide and immediately began seeking the presidential nomination. Nixon had a head start, however, spending 1966 campaigning for Republican candidates and cultivating party conservatives.

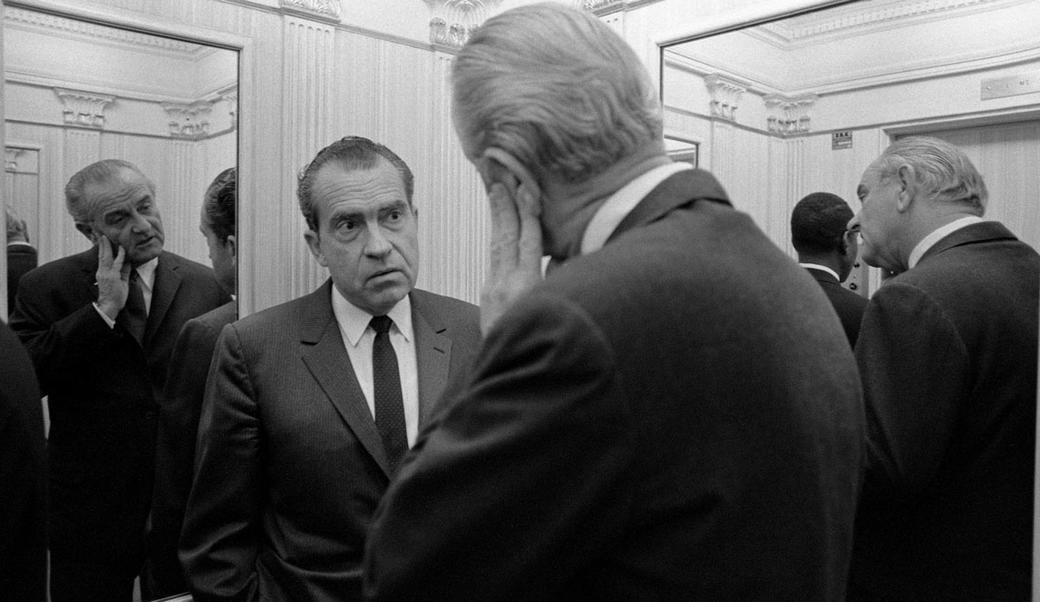

His hard work paid off. Thanks in part to an ill-timed blast from President Lyndon Johnson, who called Nixon a "chronic campaigner," the presidential hopeful found himself the center of attention right before an election in which Republicans made tremendous gains. It was going to be a Republican year anyway, with Vietnam and urban unrest dominating political debate, but Johnson's attack helped make it Nixon's year as well.

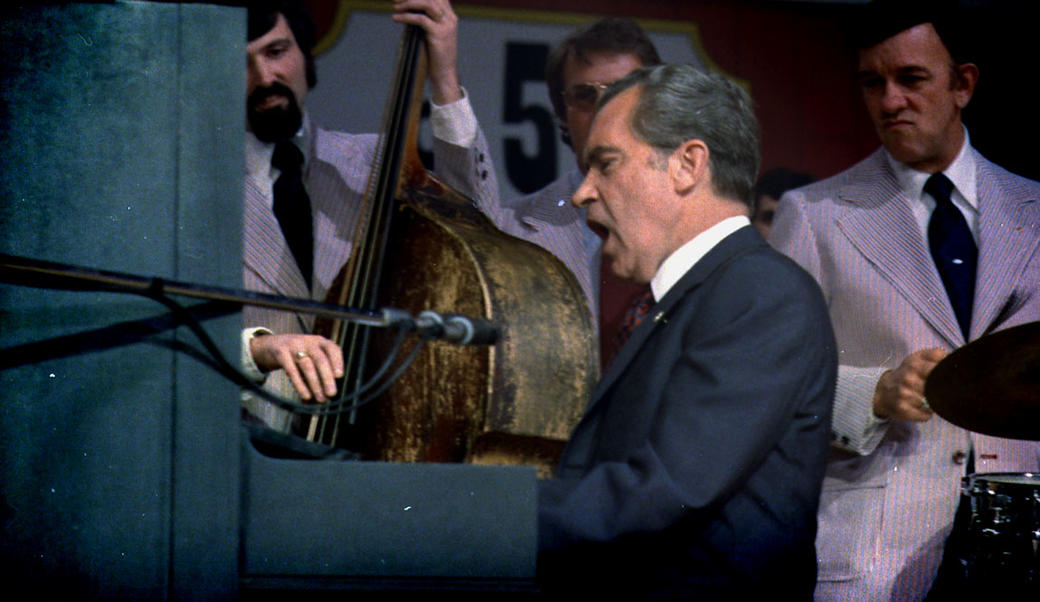

While Reagan continued to woo the conservative movement, Nixon picked off conservative leaders. Goldwater, Senator Strom Thurmond, and other mainstays of the Republican right-wing lined up behind Nixon. He entered every primary and assembled a team of media consultants who helped him create the image of a "New Nixon," more statesmanlike, less combative, more mature and presidential, an effort chronicled in "The Selling of the President 1968" by Joe McGinnis. The centerpiece of this self-recreation was a series of carefully managed television interview programs packaged by the Nixon campaign. These programs showed Nixon at his best, answering questions posed by ordinary Americans, and shielded him from questions by reporters, who sometimes brought out his worst.

At the Republican Party convention, Nixon won the nomination on the first ballot. Reagan moved to make the nomination unanimous. The presidential hopeful then tapped Maryland's governor Spiro Agnew as his running mate. In his acceptance speech, Nixon offered hope to a country in chaos: "We extend the hand of friendship to all people. To the Soviet people. To the Chinese people. To all the people of the world. And we work toward the goal of an open world, open sky, open cities, open hearts, open minds."The Republicans' orderly, well run convention was a sharp contrast to their opponents' tumultuous gathering in Chicago. The Vietnam War had split the Democratic party. Antiwar candidate Eugene McCarthy made a surprisingly strong showing against President Johnson in the New Hampshire primary, leading Johnson to withdraw from the race in late March. Robert Kennedy then entered the race, winning the California primary in June and—on the same night—losing his life to an assassin's bullet, adding to the grief of a nation still mourning the death of Martin Luther King two months earlier. At the Chicago convention, antiwar forces were defeated by Johnson loyalists, who gave the nomination to Vice President Hubert Horatio Humphrey. Outside the convention hall, Chicago police clashed with demonstrators, igniting riots.

Nixon started the general election campaign with a double-digit lead over Humphrey, even in the face of a serious third-party challenge from candidate George Wallace. Wallace came to national prominence early in the 1960s as a staunch segregationist and broadened his appeal to the Right by lashing out at antiwar demonstrators. Nixon pressed his advantages. He refused to debate Humphrey; he also raised and spent much more money than his opponent.

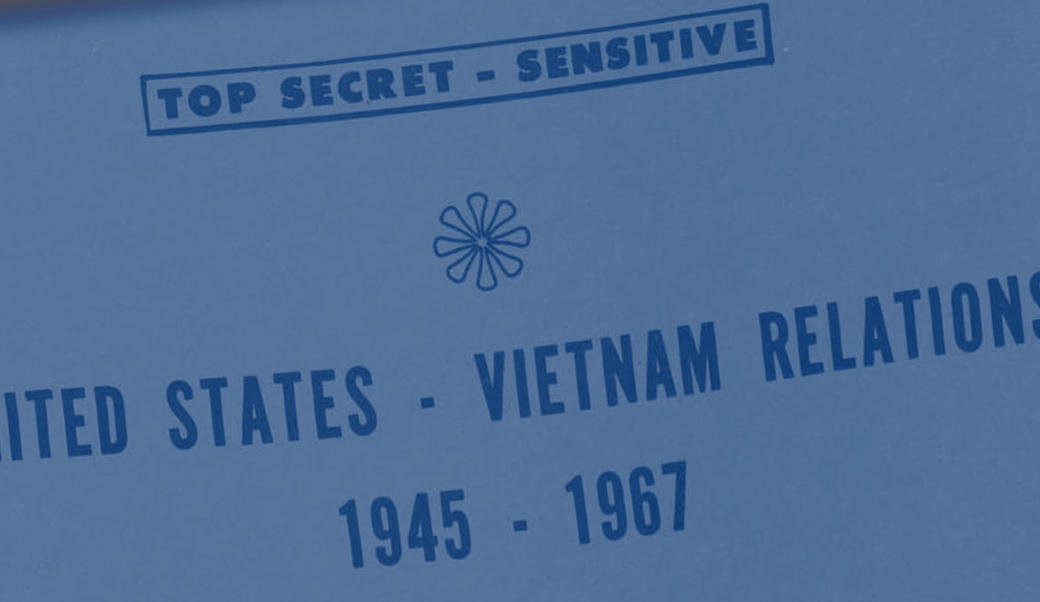

Nevertheless, by Election Day, his lead had all but vanished. Humphrey was buoyed when the North Vietnamese accepted President Johnson's proposal for peace talks in Paris in return for a bombing halt. Publicly, Nixon supported the bombing halt and the negotiations; privately, however, his campaign urged South Vietnam's government to refuse to take part in the talks. South Vietnam complied just days before Americans went to the polls and made Nixon their President. But before Nixon took office, he closed ranks with Johnson and insisted that South Vietnam take part in the peace talks.

Although it was an extremely close race with respect to the popular vote, Nixon won the electoral college by a 3 to 2 margin. Wallace's third party candidacy stole votes from both of the major parties, but hurt the Democrats more; many Southern Democrats defected and Nixon was able to win some Southern electoral votes. Only 43 percent of voters supported Nixon, hardly a mandate. In fact, he defeated Humphrey by a margin of less than 1 percent of the vote. The Democrats nevertheless maintained control of the House and Senate, making Nixon the first President elected without his party winning either house of Congress since the nineteenth century.

The Election of 1972

In hindsight, the magnitude of Richard Nixon's reelection victory in 1972—the largest Republican landslide of the Cold War—leads some to ask why the President ever got involved in the Watergate cover-up. Nixon won 49 out of 50 states, taking all but Massachusetts. He established an early lead over the Democratic nominee, Senator George McGovern of South Dakota and never lost it.

McGovern, on the other hand, stumbled early. He selected Thomas Eagleton as his running mate, only to learn later that the senator from Missouri had undergone treatment for mental illness. A political firestorm immediately erupted over whether a man with a history of mental illness should be next in line to become commander in chief in the nuclear age. McGovern hastily declared himself to be "1,000 percent" behind Eagleton. He then dropped him from the ticket. If selecting a vice president is the first presidential decision that a nominee ever makes, McGovern, by choosing and then rejecting Eagleton, had in effect admitted he made the wrong decision. Kennedy brother-in-law Sargent Shriver, an architect of John F. Kennedy's Peace Corps and Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty, replaced Eagleton, but the damage was already done.

For Nixon, it was the best year of his political life. His diplomatic opening to China reached fruition with a widely televised trip to Beijing. Détente bore fruit with the signing of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty and a summit in Moscow. And Nixon's decision to bomb North Vietnam and mine Haiphong Harbor to stop a Communist offensive proved highly popular. When Henry Kissinger announced shortly before the election that he had resolved most major negotiating issues with North Vietnam and that therefore "Peace is at hand," it was only icing on the cake.

During most of this outwardly triumphant year, however, a scandal of epic proportions was quietly growing within the administration.