With the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt on April 12, 1945, Vice President Harry S. Truman assumed the Oval Office. He surely knew he faced a difficult set of challenges in the immediate future: overseeing the final defeats of Germany and Japan; managing the U.S. role in post-war international relations; supervising the American economy's transition from a war-time to a peace-time footing; and maintaining the unity of a fractious and powerful Democratic Party.

But perhaps Truman's most daunting task was following his esteemed predecessor, who had remade American governance, the Democratic Party, and the office of the presidency during his unprecedented twelve years in office. Roosevelt's shadow would be difficult for Truman—or any Democrat, for that matter—to escape. Truman, moreover, lacked Roosevelt's stature, charisma, and public-speaking skills.

The new President did have other qualities that recommended him for the job. The public related well to Truman, thinking him hard-working and honest. Truman also seemed to relish making politically difficult decisions. Finally, Truman's experiences in Missouri politics—and especially his two electoral victories that brought him to the Senate—demonstrated a deft understanding of the various groups that made the political philosophy of liberalism and the Democratic Party the reigning institutions in American political life.

Organizing the White House

Truman asked FDR's cabinet to remain in place as he settled into the presidency. Yet the new President had little confidence in this group; by the spring of 1946, he had replaced many of those officials with men of his own choosing. Truman's appointees, however, were largely undistinguished and contributed little to his presidency. Most notably, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath became the center of a corruption scandal which cut into Truman's popularity.

Truman also inherited Roosevelt's staff of presidential advisers. By the mid-1940s, the President's staff included administrative assistants, appointments and press secretaries, and counsels to the President. It also included the Bureau of the Budget, formerly a part of the Treasury Department but, owing to the Executive Reorganization Act of 1939, now housed in the Executive Office of the President. The New Deal and the war years highlighted the increasingly important and powerful role that a President's staff played in policymaking. Several well-known members of FDR's team—like Harry Hopkins and press secretary Steve Early—did not join the Truman administration (though Hopkins answered Truman's call to service on a few occasions). Other Roosevelt staffers, like special counsel Sam Rosenman and budget director Harold Smith, continued to serve in their positions for a short time.

Truman, of course, placed his own trusted confidantes in key staff positions. Old friend Charles Ross —a highly respected Washington reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch—came on as press secretary and Senate aide Matthew Connelly became the President's appointments secretary. The two most involved staffers in the Truman administration, however, were Clark Clifford and John Steelman. Clifford, the more important of the two, advised the President on political and foreign policy issues, replacing Rosenman as special counsel to the President in January 1946. Steelman became "the assistant to the President" in December 1946, a position from which he oversaw countless administrative tasks that were required in the White House. Truman, though, fearful of losing control over the policy process, acted largely as his own "chief of staff," meeting with aides, assigning tasks, and defining his administration's agenda.

During the Truman years, the President's staff continued to grow in size. On the domestic side, the most important addition was the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA). The Employment Act of 1946 created the CEA to help the President formulate economic policy; liberal Democrats in Congress particularly wanted the CEA to be a preserve for progressives and liberal New Dealers. Truman instead staffed the CEA with a mix of conservatives and liberals, although the liberal Leon Keyserling ran the CEA after November 1949 and worked closely with Truman. More importantly, Truman treated the CEA as a set of presidential advisers, rather than as an independent body, and made sure that it remained under his control.

Leading America after Depression, New Deal, and World War

Truman took office just as World War II entered its final stages. With Japan's surrender in August 1945, he now led a nation that, for the first time in nearly two decades, was not wracked by the traumas of economic depression or world war. Truman's chief task, then, was to lay out to Americans his vision for the country's future. Two related issues—the future of New Deal liberalism and the reconversion of the American economy from a war-time to a peace-time footing—topped his agenda.

As conceived and implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his advisers, New Deal liberalism committed the federal government to managing the nation's economy and to guarding the welfare of needy Americans. Truman would have to decide whether to maintain, advance, or retreat from these basic premises. During the war, for instance, the Roosevelt administration had geared the economy to meet the nation's war needs, implementing price and wage controls, rationing and allocating resources, and setting production targets for American industry. In short, the federal government regulated the American economy to an unprecedented degree. With the war's end, Truman needed to reorient the nation's financial system towards consumer production and clarify the government's future role in the economy.

In September 1945, Truman presented to Congress a lengthy and rambling twenty-one point message that nonetheless attempted to set the post-war political and economic agenda. Truman called for new public works programs, legislation guaranteeing "full employment," a higher minimum wage, extension of the Fair Employment Practices Committee (or FEPC, a war-time agency that monitored discrimination against African Americans in hiring practices of government agencies and defense industries), a larger Social Security System, and a national health insurance system. Taken together, these requests demonstrated an interest in maintaining and building upon the New Deal. On reconversion, Truman pushed for quick demobilization of the military—a political necessity as the troops and their families clamored for a hasty return to civilian life—and the temporary extension of governmental economic controls.

Truman's program went nowhere. While he won passage of a "full employment" bill—the Employment Act of 1946—the measure had no teeth. Republicans and conservative southern Democrats in Congress were dead-set against many of the other proposed reforms, including an extension of FEPC, national health insurance, and a higher minimum wage. The public, moreover, divided over the prospects of an enlarged social welfare state and continued government intervention in the economy; liberal Democrats and key constituents of the Democratic Party supported them, but many other Americans did not.

Reconversion stuttered and stalled—and Truman received the blame. In truth, rapid reconversion would have been difficult for any President, due to the variety and challenge of its objectives: increased production of consumer goods, full employment, higher wages, lower prices, and peace between labor unions and industrial management.

Ironically, a key Democratic constituency—labor—gave Truman the most headaches. In August 1945, Truman announced that he would maintain price controls but that unions could pursue higher wages. Beginning in late 1945 and lasting throughout 1946, a wave of strikes hit the steel, coal, auto, and railroad industries, debilitating key sectors of the American economy and stifling production of certain consumer goods. Truman remained steadfast in the face of labor's demands. To end the strikes and restore industrial peace, he recommended compulsory mediation and arbitration, warned that the U.S. government would draft striking railroad workers, and even took a union—the United Mine Workers—to court. The unions backed down and returned to work, for the most part with healthy gains. But by taking such a hard line, Truman had damaged his relationship with an important element of the party coalition.

Truman's other chief economic problem was the time it took to convert from military to civilian production. Consumer goods in high demand were slow to appear on the nation's shelves and in its showrooms, frustrating Americans who desperately wanted to purchase items they had forsaken during the war. Price controls proved a particularly thorny problem. When Congress preserved the Office of Price Administration but stripped it of all its power, Truman delivered a stinging veto. As controls began to disappear in mid-1946, prices shot upward; the rise in the price of meat—which doubled over a two-week period in the summer—received the most attention. In response, the government reinstituted price controls, angering meat producers who then withheld meat from the market. A New York Daily News headline read, "PRICES SOAR, BUYERS SORE, STEERS JUMP OVER THE MOON."The combination of high prices and scarcity angered consumers and voters, who often blamed the President. One woman wrote Truman specifically with the meat problem in mind, asking him, "How about some meat?" By September of 1946, Truman's popularity rating had sunk to 32 percent. Many Americans, including the President's supposed Democratic allies, wondered if Truman could effectively lead the nation. In the congressional mid-term elections of 1946, Republicans highlighted the problems of reconversion with slogans like "Had Enough" and "To Err is Truman," winning control of both the House and Senate. The future of Truman's presidency looked bleak as the 1948 presidential election loomed on the horizon.

Republicans in Congress

Ironically, Truman's legislative predicament actually sparked his political comeback. With Congress in the hands of Republicans—rather than members of his own party who were lukewarm (at best) to his proposals—Truman could let GOP leaders try to master the challenging task of governance. Truman also could define himself in opposition to Republican initiatives and wage a rhetorical war against the Republican Party.

Truman employed this strategy in several ways. In his January 1947 State of the Union address, he identified the need for legislation to solve the persistent problems of labor unrest and strikes. He offered no solution of his own, however, proposing only a temporary commission to study the issue and a declaration that he would sign no bill attacking organized labor.

Republicans in Congress took up Truman's challenge and passed the Taft-Hartley bill, which limited the power of labor unions by curbing union participation in politics, by approving state "right to work" laws, and by allowing the President to block strikes through a judicially mandated eighty day "cooling-off" period. Truman vetoed Taft-Hartley in June 1947, declaring that it "would take fundamental rights away from our working people." Congress overrode the veto; Truman, in turn, vowed to carry out the law's provisions and he even employed several of them—including the court injunction—to bring an end to some strikes. Nevertheless, in opposing Taft-Hartley, Truman recaptured the support of organized labor.

Inflation continued to be a problem in 1947 and 1948 as well, although prices did not rise as steeply as they had in 1946. Food prices, in particular, continued to soar. Truman suggested a return to price controls, albeit with the knowledge that congressional Republicans would reject such a measure—which they did. Republicans passed legislation mandating economic controls and rationing, which Truman signed, though he declared these bills "pitifully inadequate." Democrats made hay with Republican senator Robert Taft's suggestion that Americans "Eat less meat, and eat less extravagantly," which they conflated to "Eat less." Truman had managed to make inflation a Republican problem.

Finally, in 1947, Truman reaffirmed his support for liberal initiatives like housing for the poor and federal assistance for education. He vetoed Republican tax bills perceived as favoring the rich and rejected a Republican effort to raise tariffs on imported wool, a measure he deemed isolationist. These positions, combined with his veto of Taft-Hartley and his sympathy toward price controls, situated Truman as the chief defender of the New Deal against Republican encroachments.

Truman also took a stand in 1947 on civil rights. His unsuccessful 1945 proposal to extend FEPC was, in part, an effort to court black voters so important to the Democratic Party. In the summer of 1947, Truman became the first President to address the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), to whom he declared his forthright support of African-American civil rights. Speaking to a crowd of 10,000, Truman declared that "The only limit to an American's achievement should be his ability, his industry, and his character." A few months later, his blue-ribbon civil rights commission—which he had appointed in the wake of the failure to extend FEPC—produced a report titled, To Secure These Rights, a detailed and unabashed brief for civil rights legislation.

Truman proceeded cautiously on this front, however. In early 1948, he sent his civil rights proposals to Congress, but did little to urge their passage. He also announced that he would issue executive orders—in the future—to desegregate the armed forces and to prohibit discrimination in the civil service. By early 1948, therefore, his support for civil rights was more rhetorical than substantive.

Nonetheless, as he pursued this strategy with increasing skill throughout the year, Truman stood poised to win Democratic votes. In his 1948 State of the Union address, Truman again called for civil rights legislation, national health insurance, a housing program, and a higher minimum wage. On a cross-country train tour in early 1948—dubbed a "whistle stop" tour by Republican Senator Robert Taft—Truman employed a new extemporaneous speaking style. Audiences warmed to this new public persona: the plain-spoken, hard-fighting Harry Truman from Missouri. Still, most political observers—and many Democrats—thought Truman would not win re-election in 1948.

After a rousing Democratic National Convention in which he claimed the nomination of a divided party—southerners had bolted in favor of segregationist "Dixiecrat" Senator Strom Thurmond (SC) and some progressives had supported Truman's former commerce secretary Henry Wallace - the President turned his attention to the Presidential campaign. He continued to run against the Republican Congress, even calling it into a special session to enact legislation. Truman also embraced more fully the cause of black civil rights by issuing executive orders desegregating the military and outlawing discrimination in the civil service. He won an upset victory that fall over his Republican opponent, Governor Thomas Dewey of New York. (For more details, see Campaigns and Elections.)

Fair Deal

Buoyed by his stunning victory, Truman announced an ambitious agenda in early 1949, which he called the "Fair Deal." It was a collection of policies and programs much desired by liberals in the Democratic Party: economic controls, repeal of Taft-Hartley, an increase in the minimum wage, expansion of the Social Security program, a housing bill, national health insurance, development projects modeled on the New Deal's Tennessee Valley Authority, liberalized immigration laws, and ambitious civil rights legislation for African-Americans.

Conservatives in the Republican and Democratic parties had little use for Truman's Fair Deal, however. National health insurance and repeal of Taft-Hartley went nowhere in Congress. Southern Democrats filibustered any attempt to push forward civil rights legislation. And Truman's agricultural program, the "Brannan Plan," designed to aid the family farmer by providing income support, floundered; it was replaced by a program that continued price supports. Congress did approve parts of the Fair Deal, however; Truman won passage of a moderately effective public housing and slum-clearance bill in 1949, an increase in the minimum wage that same year, and a significant expansion of Social Security in 1950.

Clearly, Truman had miscalculated in reading his electoral victory as a mandate to enact a liberal political, social, and economic agenda. Just as important, Truman regarded the "Fair Deal" as an opportunity to refashion the Democratic party into an alliance of urban dwellers, small farmers, labor, and African-Americans. Absent from this proposed coalition were white conservative southern Democrats. Moreover, public opinion polls showed that most Americans wanted Truman to protect the New Deal, not enlarge it. Likewise, Truman underestimated congressional opposition to a larger social welfare state—opposition strengthened by the public's lack of support for the Truman agenda. Whatever enthusiasm remained for the Fair Deal was lost, after the summer of 1950, amidst preoccupations with the Korean War.

Economic Growth

As Truman fought for the Fair Deal in 1949, he also battled a fairly severe economic slowdown. Both unemployment and inflation rose during the first six months of that year, heightening fears that the nation's post-war economic boom was over. Truman's economic policy sought to balance the federal budget through a combination of high taxes and limited spending; any budget surplus would be applied to the national debt. As the economy stalled, Truman in mid-1949 abandoned his hope for a balanced budget and gave some tax breaks to businesses. The economy responded by perking up in 1950. Truman's actions signaled that his primary concern was the maintenance of healthy economic growth, viewing ever-larger budget deficits as temporary expedients. It was a policy that succeeding administrations would follow repeatedly.

The Korean War, which began in June 1950, also affected the American economy. Truman and his advisers believed that American involvement in the war required economic mobilization at home. With the World War II experience in their minds—and uncertain whether the Korean War was merely the opening round of a longer and larger conflict - U.S. officials hoped that government intervention would keep unemployment and inflation under control, stabilize wages and prices, and increase military-related industrial production. In December 1950, Truman won congressional passage of the Defense Production Act and issued an executive order creating the Office of Defense Mobilization. Somewhat surprisingly, mobilization proceeded with few hitches: unemployment stayed low; inflation remained in check, albeit for a sharp, one-time surge in the last half of 1950; the hording of consumer goods subsided quickly; and military production increased. Nevertheless, many Americans complained about the government's intervention in the economy, especially its controls on credit.

Economic mobilization for the war effort did serve, though, as the setting for one of Truman's most stunning rebukes. By the end of 1951, the nation's steel industry faced a possible shut-down as labor and management could not agree on a new contract. Government mediation during the first several months of 1952 failed to end the stalemate. Throughout the ordeal, Truman's objectives were to avert a strike, maintain steel production, and stay on good terms with labor, an important Democratic constituency. In April, with no agreement in sight, Truman used his presidential authority to seize the steel industry; for the time being, it would be administered and overseen by the federal government. The seized steel companies took Truman to court to overturn his action. In June 1952, the Supreme Court declared the seizure unconstitutional by a 6-3 vote. Private management of the companies resumed, followed by a 53-day strike and a new contract, dealing Truman another political set-back.

Anticommunism and Senator McCarthy

Opposition to leftist political radicalism and the fear of subversion have long and intertwined histories in American politics and culture. As tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union intensified in 1945, fear of—and opposition to—communism became a central part of American politics and culture. Politicians and the public seemed especially concerned that American communists or foreign agents might infiltrate the American government.

In November 1946, Truman created a temporary loyalty security program for the federal government to uncover security risks, i.e., Communists. Five months later, Truman issued an executive order making the program permanent. Other government bodies also tried to stymie the alleged subversive threat of communism. The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), originally formed in 1938 with a mandate to investigate Nazi propaganda, launched an investigation of Hollywood screenwriters and directors in 1947.

Two spectacular spy cases intensified concerns over communism. In 1948, Whitaker Chambers, a former Communist and current editor of Time magazine, accused former Roosevelt aide and State Department official Alger Hiss of being a Soviet spy; HUAC investigated these charges, complete with dramatic testimony from Hiss and Chambers. Less than a month after Hiss was convicted of perjury in January 1950, the British government arrested Klaus Fuchs, a German émigré scientist who had worked on the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. Fuchs was charged with and then convicted of passing along A-bomb secrets to the Soviets with the help of American citizens David Greenglass and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg; he served nine years of a fourteen-year sentence in the British penal system. The U.S. government executed the Rosenbergs in 1953. The Hiss and Fuchs revelations were all the more shocking because the Soviets had successfully tested an atomic bomb in August 1949—years before most experts believed they would have the ability to do so.

Even though the Truman administration supported several programs designed to root out communists and "subversives" from the American government, ardent anti-communists in both the Republican and Democratic parties hammered away at the threat of communist subversion and accused the administration of failing to protect the United States. Easily the most fabulous exploitation of the issue came from Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, who in the days after the Fuchs arrest charged that the State Department was riddled with communist agents. McCarthy's fantastic allegations, the specifics of which he changed in subsequent appearances, electrified American politics by calling into question the loyalties of officials who conducted the nation's relations with the Soviets. McCarthy's charges also insinuated that Truman's loyalty program had failed miserably. McCarthy spent the rest of the Truman administration, as well as the first years of the Eisenhower administration, on a quest to expose communists in the State Department and the U.S. Army.

Truman did his best to calm the hysteria, which, by the spring of 1950, had been dubbed "McCarthyism." The President stated publicly that "There was not a single word of truth in what the Senator said." Senate Democrats organized a special subcommittee to investigate McCarthy's claims in the hope of proving them baseless. Their actions were to no avail as McCarthy—with the tacit support of most Republicans in Congress—continued to make his reckless charges and attack Truman administration officials. Military engagement in Korea and the defeats the United States suffered there only strengthened McCarthy's hand.

McCarthy was the most vocal congressional proponent of the "Red Scare," but he was far from its most effective legislator. That honor fell to Senator Patrick McCarran, a Democrat from Nevada, with whom Truman shared a mutual dislike, owing to a Senate dispute from the late 1930s over the Civil Aeronautics Act. In 1950, McCarran guided the Internal Security Act, which placed severe restrictions on the political activities of communists in the United States, through Congress. Truman vetoed the bill, claiming that it violated civil liberties; Congress easily overrode the veto, however. Two years later, Truman vetoed—on the same grounds—a McCarran-sponsored immigration bill restricting the political activities of recent immigrants to the United States. Congress again overturned Truman's veto.

Truman could do little, it seemed, to curb the excesses of the most ardent anticommunists. The political damage was immense as McCarthy, McCarran, and others charged the administration with being "soft on communism." Against the backdrop of the Korean War, Moscow's development of an atomic bomb, the fall of China to the Communists, and news reports of subversion and espionage, the "soft on communism" charge resonated with a jittery American public.

Accusations of Corruption

Accusations of corruption had dogged Truman since his earliest days in politics—a charge that was hardly surprising given his association with the Pendergast machine. During his presidency, the corruption charges proliferated, in part because they were effective political weapons for Truman's opponents. But these charges also resonated because some members of the administration did participate in ethically questionable, if not illegal, activities.

Truman's military aide, Harry Vaughan, a long-time associate of the President since World War I, was often at the center of these allegations. Vaughan clearly sought government favors for friends and businessmen; he even accepted seven freezers from an associate, one of which he gave to Bess Truman. (The freezers, however, were defective, and Bess's freezer broke after a few months.) In 1950, Democratic senator J. William Fulbright (D-AR) headed an investigation into Vaughan's activities, finding Vaughn guilty of only minor ethical and legal breaches.

Fulbright's investigation also focused on influence-peddling in the federal government, especially in the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, a New Deal-era agency charged with providing government loans to struggling businesses. The Senator uncovered a web of questionable loans and kickbacks arranged by federal bureaucrats and private businessmen. Only a few of these questionable or illegal activities involved Truman administration officials directly; much of the corruption, rather, seemed a natural outgrowth of government-business relations in the 1930s and 1940s carried on by members of both major parties.

In any event, Republicans had a field day. They crowed that Vaughan's shenanigans and the shady dealings uncovered by Fulbright were examples of the "mess in Washington." Truman's critics exaggerated the extent of the wrong-doing and corruption, and pointed, though without much of a case, to the President's role in the scandals. Throughout the firestorm, Truman stood stoutly by his old friend, dismissing all of the allegations. While the President might have proven his loyalty, he also appeared to condone Vaughan's activities. And by the time Truman moved to clean up the RFC in early 1951 in the wake of Fulbright's charges, his actions were overshadowed by other events.

That year, investigations revealed the existence of serious criminality by high-level officials in the Internal Revenue Service and the Tax Division of the Justice Department. Truman and many in the administration blamed Attorney General J. Howard McGrath, who had proven to be more well-connected than competent as head of the Justice Department. Truman gave McGrath one last opportunity to remove the wrong-doers. McGrath botched this mission so badly that Truman demanded his resignation in March 1952. The bad publicity and further taint of corruption did nothing to help Truman's public standing, although McGrath's successor, James McGranery, did effectively address the scandals.

The Decision Not to Run in 1952

Truman had written privately as early as 1950—and had hinted to aides beginning in 1951—that he would not run again for the presidency. Most scholars agree that the Korean War, battles over economic mobilization, McCarthyism, and the allegations of corruption in his administration sapped his will to run for a third term. Public opinion polls, however unreliable, showed that Truman faced an uphill battle to win re-election.

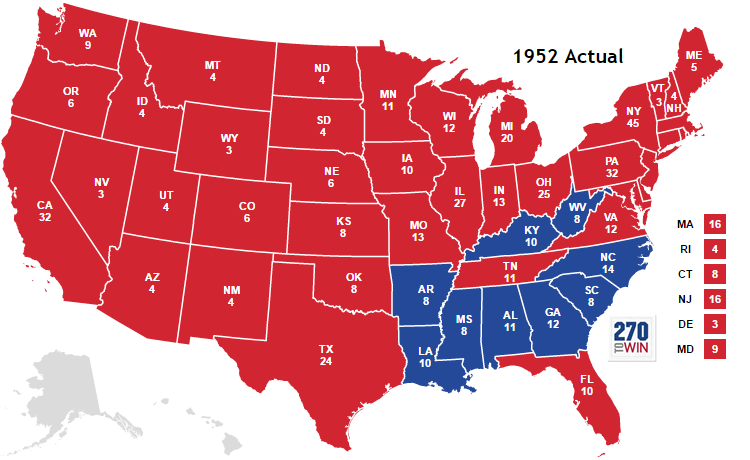

Truman kept his own counsel throughout 1950 and 1951. He maneuvered behind the scenes to recruit his successor, focusing first on Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Fred Vinson and then on General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Both men refused his entreaties, with Eisenhower announcing, in January 1952, that he was a Republican. Truman next turned to Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson, who expressed interest but refused to commit. Finally, Truman stated publicly on March 29 that he would not be a candidate for President, declaring, "I have served my country long, and I think efficiently and honestly."Governor Stevenson won the Democratic nomination at the party's convention in July, only to face the formidable Eisenhower in the general election. Truman campaigned hard for Stevenson, attacking the Republicans and Eisenhower with much of the same fury he had displayed in 1948. His once cordial relationship with Eisenhower turned bitter as a result. Nevertheless, Eisenhower proved too strong in 1952, winning a convincing victory over the Stevenson and the Democrats.

President Harry S. Truman confronted unprecedented challenges in international affairs during his nearly eight years in office. Truman guided the United States through the end of World War II, the beginning of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, and the dawning of the atomic age. Truman intervened with American troops in the conflict between North Korea and South Korea and he supported the creation of the state of Israel in the Middle East. In sum, Truman's foreign policy established some of the basic principles and commitments that marked American foreign policy for the remainder of the twentieth century.

Truman's National Security Team

Truman inherited Roosevelt's national security team, though he would transform it—in terms of both personnel and organization—during the course of his presidency. At the State Department, Truman replaced FDR's last secretary of state, Edward Stettinius, with former senator, Supreme Court justice, and war mobilization director James F. Byrnes. Byrnes handled the opening rounds of negotiations at the postwar conferences of allied foreign ministers, but he proved problematic for the President. Truman replaced him in 1947 with Gen. George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff during the war, who had attempted to mediate the Chinese civil war during 1946. Marshall, in turn, was succeeded by Dean G. Acheson, a former undersecretary of state, in 1949. Marshall and Acheson proved inspired leaders and sometimes brilliant architects of United States foreign policy.

Truman also reorganized the nation's military and national security apparatus with passage of the National Security Act in 1947. The legislation had three main purposes. It unified the Army, Navy, and Air Force under a National Military Establishment (NME) headed by a civilian Secretary of Defense. Two years later, the NME was renamed the Department of Defense and made an executive department. The National Security Act also created the Central Intelligence Agency, the leading arm of the nation's intelligence network. Finally, the Act established the National Security Council (NSC) to advise the President on issues related primarily to American foreign policy. While underdeveloped and undernourished during its first years of existence, the NSC grew in prestige and power due to U.S. involvement in the Korean War. Over the coming decades, the NSC became a significant instrument of American foreign policy.

Entering the Atomic Age

When Truman ascended to the presidency on April 12, 1945, World War II in Europe was almost over; within a month, Hitler committed suicide and Germany surrendered. In the Pacific, however, the end of the war with Japan seemed farther away. As Truman took office, military planners anticipated that total victory would require an Allied invasion of Japan. The invasion would likely prolong the war for at least another year and cost, by one estimate, over 200,000 American casualties.

Truman knew that another option might exist. The top-secret Manhattan Project was at work on an atomic bomb, a device that one of the President's advisers described "as the most terrible weapon ever known in human history." While attending the Potsdam summit in July, Truman learned that a test of the bomb had been successful. The possibility of bringing the war to an earlier conclusion was exceedingly attractive; the added heft this new weapon might give to perceptions of U.S. power, while hardly determinative, also weighed on the President's mind. With figures for a full-scale invasion of the Japanese home islands mounting and Japanese leaders offering few concrete hints of agreeing to the President's terms for unconditional surrender, Truman endorsed the use of the bomb against Japan.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Estimates of the casualties are notoriously slippery, but upwards of 100,000 people, perhaps—mostly civilians—perished instantly. Two days later, hearing no word from the Japanese government (which was in deep negotiations about whether to surrender), Truman let the U.S. military proceed with its plans to drop a second atomic bomb. On August 9, that weapon hit Nagasaki, Japan. The Japanese agreed to surrender on August 14 and then did so, more formally, on September 2. World War II was over.

Problems with the Soviet Union

Even before the end of World War II, tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States began to mount as both nations looked to shape the post-war international order in line with their interests. One of the most important flashpoints was Poland. At the Yalta conference in February 1945, the Soviet Union agreed in general terms to the establishment of freely elected governments in recently liberated areas of eastern Europe. Never fulfilling this promise, it established a Polish Communist-dominated puppet government in the spring of 1945 as the first of what would later become its eastern European satellites.

Truman hoped that the United States and the U.S.S.R. could maintain amicable relations, though he realized that conflicts would surely arise between the globe's most powerful nations. He believed that tough-minded negotiation and the occasional compromise would allow the United States nevertheless to achieve a modus vivendi favorable to American interests. A few of Truman's advisers dissented from even this guarded approach. Citing the situation in Poland, they warned that the Soviets would try to dominate as much of Europe as possible.

At Potsdam in July 1945, Truman met face-to-face with Soviet leader Josef Stalin and British prime minister Winston Churchill. The conference moved slowly and settled little. Stalin re-iterated his earlier pledge to enter the war in the Pacific against Japan—an offer Truman readily accepted—but American efforts to lessen Soviet influence over eastern Europe went nowhere. Nonetheless, as the conference came to an end, Truman wrote to Bess, "I like Stalin . . . He is straightforward. Knows what he wants and will compromise when he can't get it."In the coming months and years, Truman would change his opinion. Potsdam had been a personal success for Truman—he appeared to get along with his fellow heads of state—but the inability to settle outstanding issues, such as the future of Germany, the boundaries of postwar Poland, and the nature of wartime reparations hinted at serious underlying differences between the two nations. Secretary of State Byrnes tried in vain to work with the Soviets through the last months of 1945 and into early 1946, though without much success. At the same time, the Soviets tightened their control over eastern Europe and attempted to extend their influence into Turkey and Iran. The United States blunted Soviet intentions in those two nations through diplomacy and a show of military strength. Stalin heightened tensions with a fiery speech in February 1946, predicting a coming clash with capitalism.

The Early Cold War

Each of these developments frustrated and worried American leaders. Truman told Byrnes in January 1946, "I'm tired babying the Soviets." Others agreed. In February, George F. Kennan, the temporary head of the American embassy in Moscow, sent his assessment of Soviet foreign policy to Washington in what became known as the "long telegram." Kennan argued that the Soviets, motivated by a combination of Marxist-Leninist ideology and traditional Russian security concerns, were bent on expansion and were irrevocably opposed to the United States and the West, as well as to capitalism and democracy. He urged American leaders to confront and contain the Soviet threat. Two weeks later, former British prime minister Winston Churchill, speaking in Fulton, Missouri, declared that the Soviets were bringing an "iron curtain" down across Europe—and that the United States and Britain needed to vigorously oppose Soviet expansionism. Kennan's analysis gave American officials a framework for understanding the Soviet challenge, Churchill's formulation brought the threat home to the public at-large.

Relations between the two nations continued to worsen in 1946. Britain received a $3.75 billion loan from the U.S. government to help it rebuild. In Stuttgart, Germany, Secretary of State Byrnes committed the United States to the reconstruction of that country both economically and politically—and promised to keep troops there as long as necessary. These two decisions hinted at an emerging worldview among government policymakers: American interests required more active protection from Soviet encroachment. It came as little surprise, then, when Truman dismissed Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace in September 1946 after Wallace gave a speech repudiating the administration's anti-Soviet foreign policy.

America sharpened its approach toward the U.S.S.R. in 1947. The President and his advisers grew more concerned that west European nations, still reeling from the devastation wrought by World War II, might elect indigenous Communist governments that would orient their nations—politically, economically, and militarily—toward the Soviet Union. Moreover, after the British government told American officials that it could no longer afford to serve as the watchdog of the eastern Mediterranean, Truman announced in March 1947 what came to be known as the Truman Doctrine. He pledged U.S. support for the pro-Western governments of Greece and Turkey—and, by extension, any similarly threatened government—arguing that the United States had a duty to support "free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures." In the summer of 1947, Secretary of State George Marshall announced a multi-billion dollar aid program for Europe, which became known as the Marshall Plan, that he hoped would encourage both political and economic stability and reduce the attraction of communism to Europe's suffering populations.

In 1948, the final pieces of the Cold War chessboard began to fall into place. In February, Soviet-backed communists seized control of Czechoslovakia, the last remaining independent democracy in Eastern Europe. In March, the Truman administration won congressional approval of the Marshall Plan. And throughout the spring and summer, the United States, England, and France—each occupying a zone of Germany—accelerated the process of merging those regions into a separate country that, by 1949, would become West Germany. The Soviets responded by blockading western access routes to Berlin which, while in their zone, was administered jointly by all four powers. Truman, determined not to abandon the city, ordered an airlift of food and fuel to break the blockade.

The Berlin stand-off lasted until May 1949, when the Soviets called off the blockade in return for a conference on the future of Germany. The meeting ended in failure after Stalin refused a U.S. and British offer to make the Soviet zone part of a democratic, unified Germany; the country would remain divided between West and East until October 1990. Just as important, the February 1948 Communist coup in Czechoslovakia and the Soviet-American confrontation over Berlin spurred the creation of an alliance, largely on the invitation of European statesmen, between the United States, Canada, and Western Europe—what became known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO—to counter Soviet power. By mid-1949, Europe was divided politically, economically, militarily, and ideologically.

That year also marked the end of the U.S. nuclear monopoly. Truman had hoped that in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the development of atomic energy (for both peaceful and martial uses) would be placed under U.N. control. In early 1946, the Soviets rejected the U.S.-sponsored plan, which would have left the American atomic monopoly in place. Instead, the Kremlin redoubled its efforts to build a bomb which, through the aid of atomic espionage, came to fruition much more quickly than American policymakers and intelligence experts ever predicted.

Moscow's successful test of an atomic weapon in the late summer of 1949 forced the Truman administration to re-evaluate its national security strategy. Truman decided in January 1950 to authorize the development of an even more powerful weapon—the hydrogen bomb—to counter the Soviets, thus accelerating the Cold War arms race. In September, Truman approved a National Security Council document—NSC-68—that reevaluated and recast American military strategy. Among other things, NSC-68 stressed the need for a massive buildup of conventional and nuclear forces, no matter the cost. Truman greeted NSC-68, and its military and economic implications, with ambivalence, though the war in Korea, which began in the summer of 1950 and made the danger of armed challenge from the U.S.S.R. seem real and perhaps immediate, led to a more rapid implementation of the document's findings.

The United Nations

In the years after World War II, Truman worked diligently to assure that the United Nations—conceived by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a forum in which differences between nations could be resolved before they led to war - would be a significant player in international life. For the most part, he succeeded.

The new President sent a bipartisan delegation to the United Nation's founding conference in San Francisco in mid-1945, believing it essential that both of the major American political parties endorse the organization. The major roadblock to the formation of the United Nations came from the Soviets, who were slow to join. Truman managed to secure their participation after sending special emissary Harry Hopkins to Moscow. Some Americans would later argue, however, that the price of that participation—American acquiescence to a reorganized Polish government allied with the Soviets—was too steep. Nonetheless, the San Francisco Conference adjourned in June 1945 after its participating nations, including the Soviets, signed the founding U.N. Charter.

The United Nation's most significant accomplishment during the Truman years came during the Korean War. In the wake of North Korea's invasion of South Korea, the U.N. Security Council met, officially condemned North Korea's aggression, and pledged military support to South Korea. Though the United States provided most of the U.N. troops that fought in the war alongside the South Koreans, these forces were part of a multilateral effort. The Soviet Union, a member of the Security Council, could have vetoed U.N. involvement in the war were it not for their boycott of the meeting; Moscow was protesting the U.N.'s failure to seat a representative of the newly established—and communist—People's Republic of China.

Success and Failure in Asia

In Japan, which the United States occupied at the conclusion of World War II, General Douglas MacArthur oversaw a Japanese economic recovery and political reformation. Japan's new constitution took its cues from the ideals embodied in the American constitution. With the onset of the Korean War, the Japanese economy began its slow and steady rise to prominence, peaking in the 1980s.

The United States and the Truman administration proved less successful in shaping China's political future. In the wake of World War II, civil war resumed between supporters of nationalist Chinese leader Jiang Jieshi and the forces of Communist leader Mao Zedong. Truman sent General George C. Marshall to China in 1946 in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to mediate the conflict and form a coalition government. The administration determined privately that no amount of American aid could save Jiang, that western Europe more urgently required U.S. funding, and that the triumph of Mao's forces would not be disastrous to American interests. By August 1949, the State Department would issue a "white paper" outlining the administration's position on China and the reasons for the coming communist victory.

Two months later, on October 1, 1949, Mao declared the founding of the People's Republic of China. With Jiang's forces in full retreat to the island of Formosa, the President and his advisers confronted the firestorm in American politics touched off by the Chinese Communist victory. Republicans in Congress, including a group who wanted to reorient American foreign policy away from Europe and toward Asia, howled that the Truman administration had "lost" China. After Mao and Stalin agreed in early 1950 to a mutual defense treaty, critics of the administration's China policy redoubled their attacks. In this era of the Red Scare—Senator Joseph McCarthy leveled his infamous allegations regarding communists in the State Department in February 1950—the "loss" of China constituted a damning political charge.

The Korean War

Truman's troubles in Asia exploded on the Korean peninsula. In the wake of World War II, Korea had been partitioned at the 38th parallel, with the Soviets supporting a communist regime north of that boundary and the Americans a non-communist one in the south. On June 25, 1950, North Korea launched a surprise invasion of South Korea. The United Nations immediately condemned North Korea, while Truman and his advisers in Washington discussed the American response. Certain that the Soviet Union lay behind the invasion, they reasoned that failure to act would lead U.S. allies to question America's commitment to resist Soviet aggression. Truman resolved not to repeat the mistake of Munich, where the European powers appeased and condoned Hitler's expansionism. Scholars now know that the invasion was the brain-child of North Korean leader Kim Il-sung and that Stalin acceded to it only after making clear that the Soviets themselves would not become involved militarily and that Mao provide ground troops. Ultimately, the Soviets did provide the North Koreans with air support.

Truman ordered the American military, under the direction of General Douglas MacArthur, to intervene. The first U.S. troops did little to stop the onslaught as North Korean forces made rapid progress in their march down the peninsula. By August, the Americans were holed-up in a defensive perimeter on the southeastern tip of South Korea. MacArthur launched an audacious and risky counter-attack the following month that featured an amphibious landing behind enemy lines at Inchon on the western coast of South Korea, near the capital of Seoul.

MacArthur's gamble worked; American forces rapidly drove the North Koreans back to the border at the 38th parallel. MacArthur then received permission from the Truman administration to cross the border to secure the final defeat of North Korea and the reunification of the country. The danger, though, was obvious. The Soviet Union and China both bordered North Korea and neither wanted an American-led military force, or an American ally, on their doorsteps. In mid-October, meeting with the President at Wake Island, MacArthur told Truman that there was "very little" chance of Chinese or Soviets intervention. At the same time, however, the Chinese warned American officials though third-party governments that they would enter the war if the United States crossed the 38th parallel.

Disregarding these warnings, American forces pushed northward throughout October and into November 1950, coming to within several miles of the Chinese border. The Chinese entered the battle in late November, launching a massive counter-attack that threw the Americans back south of the 38th parallel; an American response in the spring of 1951 pushed the front north to the 38th parallel, the status quo antebellum. A brutal and bloody stalemate ensued for the next two years as peace talks moved forward in fits and starts.

American involvement in Korea brought Truman more problems than successes. After General MacArthur publicly challenged the administration's military strategy in the spring of 1951, Truman fired him. MacArthur returned home a hero, however, and Truman's popularity plummeted. Against the backdrop of McCarthyism, the failure to achieve military victory in Korea allowed Republicans to attack Truman mercilessly. Indeed, the war so badly eroded Truman's political standing that the President's slim chances of winning passage of his "Fair Deal" domestic legislation disappeared altogether.

Despite these setbacks, Truman's decision to stand and fight in Korea was a landmark event in the early years of the Cold War. Truman reassured America's European allies that the U.S. commitment to Asia would not come at Europe's expense—a commitment made more tangible in 1951 by increased American troop deployments to Europe and not Korea. The President thus guaranteed the United States to the defense of both Asia and Europe from the Soviet Union and its allies. Likewise, the Korean War locked in the high levels of defense spending and rearmament called for by NSC-68. Finally, the American effort in Korea was accompanied by a serious financial commitment to the French defense of a non-communist Indochina. In a very real sense, Korea militarized the Cold War and expanded its geographic reach.

The Creation of Israel

Between 1945 and 1948, Truman wrestled with the Jewish-Arab problem in British-controlled Palestine. Britain had searched for a solution to the conflict between Palestine's Jewish minority and Arab majority since the end of the first world war, but with little success; Arabs repeatedly rejected the British suggestion that a Jewish "national home" be created in Palestine. In February 1947, the British government, straining to uphold its other imperial commitments and with its soldiers constantly under attack by Jewish militias, announced it would shortly pass control of Palestine to the United Nations. The United Nations, in August 1947, proposed to partition Palestine into two states, one for an Arab majority and one for the Jewish minority. Jews, by and large, accepted this solution, while Arabs vigorously opposed the plan, as they had for the preceding decades. The prospect of partition ignited a savage and destructive guerilla war between Arabs and Jews in Palestine.

The question Truman faced was whether to accept the U.N. partition plan and the creation of a Jewish state. While Truman personally sympathized with Jewish aspirations for a homeland in the Middle East, the issue involved both domestic and foreign concerns. The President and his political advisers were very aware that American Jews, a major constituency in the Democratic Party, supported a state for their co-religionists in the Middle East. In an election year, Democrats could ill afford to lose the Jewish vote to Republicans. On the other hand, Truman's foreign policy advisers, especially Secretary of State Marshall, counseled strongly against American support for a Jewish state. They worried that such a course was certain to anger the Arab states in the region and might require an American military commitment. As at least one high-ranking Defense Department official argued, access to oil, not the creation of a Jewish homeland, was America's priority in the Middle East.

In November 1947, Truman ordered the American delegation at the United Nations to support the partition plan. In the following months, though, bureaucratic battles among presidential advisers over the wisdom of the plan intensified, and Truman apparently lost control of the policy-making process. He ended up endorsing a plan—by mistake, apparently—that would have established the Jewish state as a United Nations trusteeship, rather than as an autonomous entity. Truman back-tracked furiously from his remark, though without clarifying U.S. intentions. Events in Palestine forced the President's hand, however. The military triumph of Jewish nationalists over their Arab opponents in the guerilla war made it clear that the Israeli nation would soon come into being. On May 15, the United States, at Truman's direction, became the first country to recognize the state of Israel.

Harry Truman lived for nineteen years after leaving the White House in 1953. He and his wife Bess returned to Truman's hometown of Independence, Missouri, where Truman spent his post-presidential years guarding and constructing his legacy and place in history. He also continued to comment on political events of the day.

Truman selected Independence as the site for his presidential library and oversaw its construction. Upon its completion, Truman spent a good deal of time at his office there, until health concerns in the mid-1960s limited his mobility and forced him to remain at home. At the library, Truman relished receiving important guests, meeting scholars who were studying his presidency, and speaking to groups of visiting school children. His trademark feistiness remained intact; he told one young history professor that he had better go home and read his books before trying to interview him again.

In 1955, Truman published the first volume of his memoirs; the second volume followed in 1956. Unfortunately, he hired ghostwriters and research assistants of questionable ability to help him through the process. As a result, the volumes were poorly organized, marred by leaden writing, and offered neither a comprehensive account of the Truman presidency nor many insights. Nonetheless, both volumes sold well upon their release.

Truman remained active in American politics after he left the White House. Eisenhower's handling of the presidency annoyed and angered Truman, who regularly criticized the administration's policies and politics in public appearances. He actively campaigned against Eisenhower in 1956. The personal relationship between the two men, already strained after Ike declared in 1952 that he would run for the Republican nomination, deteriorated throughout the eight years of Eisenhower's presidency. Truman had better relations with Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. He expressed reservations about Kennedy in 1960—thinking him too young and too Catholic to be a successful Democratic presidential nominee—but once in office, Kennedy and his wife charmed the ex-President. Truman felt even more comfortable with President Johnson, with whom he had enjoyed cordial relations while Johnson was on Capitol Hill. He never got along with President Nixon, however.

Truman found time to relax and rest in his post-presidential years. He was never far from his favorite bourbon and enjoyed clanking glasses with the old friends, political allies, and dignitaries who came through Independence. While his health permitted, he took regular walks around town. He traveled some, including a 1953 auto trip to New York during which a policeman stopped him on the Pennsylvania Turnpike for making an illegal lane change. It was Truman's only attempt at a long drive after leaving the presidency.

Harry S. Truman died on December 26, 1972, of old age rather than any specific sickness. Bess vetoed plans for an elaborate state funeral and arranged an Episcopalian service in the auditorium of the Truman Library. She had a Baptist minister and the Grand Masonic leader of Missouri conduct the proceedings. Truman was buried in the courtyard of his presidential library, with a simple stone epitaph that he himself had prepared. It listed the dates of his birth and death, the birth of his daughter, and his public offices from district judge to President of the United States. When Bess joined him ten years later, her marker read "First Lady of the United States."

Few Presidents were as dedicated to their family as Harry S. Truman. Although his father died in 1914, Truman’s mother, Martha Ellen, lived into her nineties—long enough to see him succeed President Franklin D. Roosevelt. “Mama,” as Truman called his mother, passed away in 1947. She and her son had a very close relationship. A devoted Democrat and an astute political observer, she avidly supported her son's political career. In 1944, she chaired the first meeting of the female women workers in his campaign for the vice presidency. Truman corresponded regularly with his mother, often revealing in wonderfully expressive language his innermost thoughts about political affairs and family.

Truman's younger sister Mary Jane and brother Vivian were always close to him. Mary Jane, having never married, lived at home with "Mama" Truman and thus shared in all the news and attention that came their way. Vivian, who worked as the district director of the Federal Housing Administration, kept Truman apprised of political news from Missouri. The President often consulted his brother before making patronage decisions involving Missourians.

Truman was a doting and protective father to his daughter Mary Margaret. When Truman moved to Washington to serve in the Senate, Margaret was ten-years old. Thereafter, she would live half the year in Independence and half in Washington, until she was in high school. During the White House years, Margaret attended George Washington University. After graduating, she pursued a career as a vocalist.

Margaret performed frequently in public—she even went on a successful thirty-city tour in 1947—and showed some promise. Music critics, however, did not always offer good reviews of her performances. As a father, Truman could not abide the criticism, although he almost never responded publicly. On one particularly stressful occasion in December 1950, at the low point of the Korean War, his anger got the best of him. After reading a poor review of Margaret's performance in the Washington Post, Truman wrote the author: "Some day I hope to meet you. When that happens you'll need a new nose, a lot of beefsteak for black eyes, and perhaps a supporter below!" A public uproar ensued after the reviewer released Truman's note to the press. Truman, though, maintained that the public understood he was just protecting his daughter, like any good father. Margaret finally gave up her quest for a musical career to marry Clifton Daniel, a highly successful New York newspaper editor, in 1956. They eventually had four children.

Harry Truman's life in the White House followed a regular routine. Truman usually awoke at 5:00 in the morning, dressed, and took a vigorous one or two-mile walk (at the Army's 120-steps-per-minute pace) around the White House grounds and neighborhood - wearing a business suit and tie! After an assassination attempt in 1950, the Secret Service took the President to various undisclosed locations for his daily walk. He then had a rubdown, a shot of bourbon, and a light breakfast. He tried to lunch each day with Bess and take short afternoon naps. At mid-day, Truman often took a few laps in the White House swimming pool, swimming with his eyeglasses on. In the evening, if no business was at hand, he and Bess would enjoy a cocktail, eat dinner, and then listen to music or watch a movie. Once or twice a week, he would slip away to a stag poker party with his male friends at a private home, seldom returning before midnight. Truman loved to tell and hear dirty jokes, and enjoyed visiting with and pulling strings for his old Army friends. He also relaxed by taking trips aboard the presidential yacht Williamsburg or by vacationing at the naval base in Key West, Florida. Truman almost always invited his male friends—and rarely Bess or Margaret—along on these excursions.

In 1950, just over 150.7 million people were living in the United States. Nearly two-thirds resided in urban or suburban areas. The average American white male could expect to live to age sixty-six, while white women usually lived to age seventy-two. African-American life expectancy, however, was considerably lower.

The most important demographic change during the Truman years, however, was the growth of the American population as a whole, which between 1940 and 1950 grew by over 14 percent, or 19 million people. Similar—and even larger—population increases had occurred in the first decades of the twentieth century, but that growth was fueled largely by immigration to the United States. Congress, however, passed laws in the 1920s that severely restricted immigration; these laws stayed in effect until 1965, meaning that the growth of the U.S. population in the 1940s was almost exclusively home-grown (with those immigrants who did arrive coming largely from Germany, Great Britain, and Canada).

The American Family

The engine of American population growth was the "baby boom." After years of depression and war, Americans, quite simply, were having more children. In 1940, American families had, on average, 2.6 children; by 1950 that number had jumped to 3.2. The baby boom was only one of the massive changes underway in the structure of the American family during the years immediately following World War II. The marriage rate began to rise rapidly during the Truman years; statistics showed that during the 1950s, 97% of American women and 94% of American men between the ages of 18 and 30 were married. Americans also got married at younger ages than at any time in the twentieth century. Finally, Americans stayed married in the 1950s; after an initial surge in the divorce rate, following the return of American veterans from overseas, the number of couples splitting up dropped precipitously.

Higher marriage and birth rates were just some of the significant changes in the lives of American women in the postwar years. During World War II, women joined the workforce in large numbers; by 1945, 19 million women were working outside the home. Two million women left the workforce in the immediate post-war years. Some did so out of choice, but many left because of federal employment policies which privileged returning veterans at the expense of working women. Nonetheless, women's participation in the workforce continued to rise in the late 1940s and through the 1950s, though with some caveats. Those who joined the workforce were older women, women of working-class means, and women of color. Moreover, these women often took jobs that paid poorly, offered fewer chances for advancement, and were less likely to be unionized.

If the increasing number of American women in the workforce marked one trend during the post-war years, another involved a renewed emphasis on domesticity. American women—white and black—were told by a host of experts that their primary responsibilities lay in the home. Their task was to raise and care for children, and ensure that husbands returned each day from work to a happy and well-cared for home. For women who worked outside the home, such advice meant double-duty as both homemaker and worker. Women who stayed at home, however, faced the possibility of an often intellectually and emotionally stultifying life, what the author Betty Friedan called "the problem with no name" in her groundbreaking 1963 book on domesticity, The Feminine Mystique.

Suburbia

One important development in American society during the Truman years was the rise of the suburbs, communities that sprung up adjacent to, but outside of, American cities. Of the nearly two million new homes built in the United States between 1945 and 1950—the outlines of this trend had become apparent in the 1920s, though the Depression and then the war cut it short—more than 80 percent were built in the suburbs. Inexpensive federal government mortgages, innovations in home construction, a fast-growing population, and burgeoning economic prosperity all contributed to the suburban housing boom.

Levittown, New York, just twenty-five miles from Manhattan, was the archetypal suburban community. The builder William Levitt put up 17,000 houses—and parks, stores, and churches to serve their residents—on several thousand acres of farmland in the 1940s; the venture proved such a success that Levitt built other suburban communities in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Americans, who were marrying and having children at dizzying rates, flocked to suburbs like Levittown for obvious reasons. Housing was affordable, the schools were good, and the streets were safe. The neighborhoods were made up of young families, providing a sense of community and shared experience.

Not all Americans were fans of the suburbs, however. Critics noted that suburban housing all looked the same, as did its residents: white, middle-class, young families in which the husband worked and the wife stayed at home with the children.

African-Americans

During the Truman years, African-Americans continued to move from the rural south to the urban north, a migration that began during the 1930s. One million blacks left the south in the 1940s; another 1.5 million left in the 1950s. In the north, Blacks found both more freedoms and better jobs, though they still encountered racial discrimination and violence when they moved into almost exclusively white neighborhoods later in the decade. Historians now trace both the origins of the divisive racial politics that split the Democratic party and the beginning of the so-called "urban crisis" to the immediate post-war years.

While the African-American civil rights movement would not explode in the national consciousness until the mid-1950s with the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board decision and the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott led by Martin Luther King, important gains in civil rights occurred during the Truman years. In 1946, the Supreme Court declared segregation in interstate bus travel unconstitutional. In 1948, the Court struck down restrictive housing covenants. And in both 1948 and 1950, the Court issued three separate rulings that chipped away at segregation in higher education, each of which helped pave the way for the Brown decision.

Civil rights groups were active during the Truman years as well. The NAACP pressed the federal government to desegregate the military, set up a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission, and outlaw discrimination in the federal government employment practices. After the Court's 1946 decision concerning interstate busing, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) began a series of "freedom rides" in the upper south to see whether the Court's ruling would be enforced. The most public demonstration of African-American equality, however, probably occurred in 1947 when Jackie Robinson, a second basemen for the Brooklyn Dodgers, integrated the "National Game," major league baseball. Robinson's prowess on the field—he led his team to the pennant and won the "Rookie of the Year" award—was surpassed only by his quiet dignity as he endured countless insults from fans, opponents, and even some teammates.

Labor

As Truman took office, American labor unions had reached the apogee of their power. In 1945, nearly 30 percent of all American workers were in a union, which gave organized labor significant political power. Quite simply, labor was the key member of the "New Deal coalition" assembled by Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Democratic Party because it could deliver millions of votes. But labor's power was apparent not just on election day but in the programs and governance of the New Deal and the American World War II homefront. The was especially true during the war, when labor's representatives, working with politicians, policymakers, and corporate leaders, helped organize the American economy to maximize production, provide fair wages, and avoid strikes and strife.

In the immediate post-war years, however, labor's power began to wane. Conservatives in both the Democratic and Republican parties looked to curb—and perhaps even end—the reformist impulse of New Deal and World War II-era liberalism. In practice, this meant trying to reduce labor's political power and eradicating government policies that gave unions a voice in the nation's political economy. The reconversion of the American economy that began in earnest in 1946 brought an end to many of the World War II commissions in which labor participated. Just as important, conservatives, backed by business interests, managed to pass the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, empowering industry and its political allies in their attack on labor. Finally, President Truman, unlike his predecessor, proved an ambivalent ally of labor. While he sympathized with the working man's desire for a better life, Truman, who was once a small businessman himself, possessed a general dislike of labor unions and the tactics embraced by their leaders. His antipathy for union leaders like John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers was at times immense.

But labor's influence in the post-war years also ebbed because its strategies for maintaining and extending its power had failed. Through most of the twentieth century, unions had failed to gain a foothold in the South, where conservative politicians, local elites, and businessman feared that such progressive organizations would challenge the region's political, economic, and racial orders. During World War II, however, more than 800,000 workers, including over 250,000 blacks, joined unions. If the CIO could continue to organize the south, it reasoned that its political power—both nationally and locally—would grow accordingly. In 1946, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), one of the country's two most important labor federations, launched Operation Dixie, an effort to build unions in southern states. The CIO sent down hundreds of organizers states, opened up union offices, and aggressively courted southern workers. Operation Dixie failed horribly, however. White workers proved largely unwilling to join interracial unions, southern companies and industries counterattacked with aggressive anti-union propaganda, and union organizers were constantly harassed, threatened, and sometimes violently beaten.

Labor unions also suffered in the late 1940s and early 1950s because of the "Red Scare" (see below). Red Scare political culture proved especially corrosive to labor unions as its proponents questioned whether organizations or persons with liberal or progressive political agendas—like unions—might be allied with the Soviet Union or sympathetic to communism. In fact, a small number of union members were communists, a reality which union opponents exploited and exaggerated in their political campaigns. Second, anticommunists in unions vigorously purged their organizations of communists or suspected communists, a measure which proved divisive and morale-sapping, depriving unions of some of their best organizers.

The Red Scare

The Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s was not an anomaly; American history contains numerous incidents of violence and suppression of leftist political radicalism. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution and the rise to power of Russian communists in 1917, persecution of American communists produced what some historians call the "First Red Scare."The emergence of the Cold War and the dawning of the atomic age meant that the politics of anticommunism—practiced in its more benign form by President Truman, in a slightly less benign form by young politicians like Congressman Richard Nixon, and in a malevolent and destructive form by Senator Joe McCarthy—became a fact of American political life during the Truman years. Just as striking though, the Red Scare of the 1950s had both an unprecedented vitality and an extensive reach, affecting almost all aspects of the American experience. Films, television shows, museum exhibits, popular magazines, and comic books often portrayed communism as an anti-American virus fomented by American communists and leftists, Soviet agents, and suspicious foreigners who threatened to infect an unsuspecting public. Opening a copy of the March 4, 1947, Look magazine, for example—a glossy, picture-laden popular weekly—readers could enjoy an article entitled, "How to Spot a Communist." Americans could go to the movie theatre and see "The Red Menace (1949)" or "I Was a Communist for the FBI (1952)," propaganda films that warned of the communist threat in the United States and showed model Americans fighting it (though neither of these films, nor others of the genre, did well at the box office).

Still, it should not be surprising that the anticommunist crusade and fervor spread to local communities and local governance. Thirteen states established their own versions of House Committee on Un-American Activities, and many more states passed ordinances that either made communist organizations illegal or forced them to register with the appropriate authorities. State and local governments launched investigations of employees suspected of communist-leanings. Some of the most ardent anti-communist hunts occurred in the field of education, where local school boards investigated teachers for suspected communist leanings; at colleges and universities, some professors were fired for past or present communist affiliations. In sum, thousands of Americans were subjected to investigations, with hundreds losing their jobs and livelihoods. Many more lived in fear of the accusatory dragnet.

The history of the "Red Scare" raises an important question: how significant was the threat posed by American communists and Soviet espionage in the United States? With the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, scholars have gained access to the Soviet Union's archives, in which they have found evidence of a fairly extensive Soviet espionage effort penetrating all branches and levels of the federal government. Moreover, these newly discovered Soviet documents reveal that the leadership of the American communist party took its orders from the Soviet Union and worked assiduously to recruit Soviet agents from the American population. Some scholars believe that these findings justify the extensive efforts to combat communism in the United States that occurred in the early 1950s. Other scholars disagree, conceding that while the new evidence demonstrates convincingly that the Soviet Union was directing such espionage, the anticommunist purges of the Truman years were overly destructive and indiscriminate.

When Harry S. Truman left the presidency in January 1953, he was one of the most unpopular politicians in the United States. The Korean War, accusations of corruption in his administration, and the anticommunist red-baiting of McCarthy and his allies had all contributed to the President's poor standing with the public. Truman's reputation, though, began to revive soon after he returned to private life. In part, this was because Americans began to see Truman as a feisty everyman from "Middle America" rather than a partisan Washington, D.C., politico.

But Truman's stature also rose in subsequent years because it became easier for both scholars and the public to discern and appreciate his significant contributions. Truman's conduct of American foreign policy deserves special commendation. The President and his advisers recognized that the Soviet Union threatened the political and military balance of power, as well as the healthy economic intercourse, that favored the United States and its allies in the aftermath of World War II. Truman responded to the Soviet challenge with a range of political, diplomatic, military, and economic initiatives designed to contain Soviet power and to construct an American-led bulwark against communism. In large measure, American officials followed Truman's approach to U.S.-Soviet relations until the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s. Several Truman foreign policy programs remain central to America's international posture even today. Commitments to Israel and South Korea are still hallmarks of U.S. policy towards the Middle East and Asia, respectively. Likewise, the United States remains the prime member of NATO.

Truman also left his mark on domestic affairs. He oversaw the conversion of the American economy from its World War II footing to one that emphasized both consumer and military production. While not without problems, this transition occurred about as smoothly as possible. Truman protected the New Deal and—with a rise in the minimum wage in 1949 and the enlargement of Social Security in 1950—built upon its achievements. He pushed forward the cause of African-American civil rights by desegregating the military, by banning discrimination in the civil service, and by commissioning a federal report on civil rights. Just as important, Truman spoke out publicly on the matter.

Finally, Truman engineered one of the most unexpected comeback victories in American political history. The dispiriting 1946 mid-term elections that gave the Republicans control of Congress, paired with the prospect of facing an accomplished Republican candidate like New York governor Thomas Dewey, dimmed Democratic hopes for a Truman victory in the 1948 presidential election. Truman, though, campaigned relentlessly and effectively, making congressional Republicans the main issue in the election. He defeated Dewey convincingly in November 1948 when almost no knowledgeable observers gave him a chance.