Before he became President, Dwight D. Eisenhower had to balance family life against the obligations of military life. Duty took him to many different locations within the United States and around the world. At various times during the 1920s and 1930s, he and Mamie lived in Paris and the Panama Canal Zone, Washington, D.C., and Washington State. During their first 35 years of married life, the Eisenhowers moved more than 30 times.

They began raising a family in 1917 with the birth of a son, Doud Dwight, fondly known as "Icky." As they celebrated Christmas in Camp Meade, Maryland, in 1920, "Icky" became ill with scarlet fever, then a disease that physicians could do nothing to cure. In early January, "Icky" died. Eisenhower later wrote, "This was the greatest disappointment and disaster of my life." They had a second son, John, in 1922. Like his father, he graduated from West Point and then spent two decades in the Army, reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel. He served his father, the President, as a military aide and eventually became an accomplished military historian.

During World War II, military life imposed real hardships, as the Eisenhowers were separated almost continuously for more than three years. After eighteen months apart, they had two weeks together in January 1944, when Eisenhower returned to Washington from London to discuss preparations for the D-Day operation. More than a year later, after Germany surrendered, Eisenhower asked General George C. Marshall, the wartime chief of staff, if Mamie could join him in Europe. Marshall said no, as it would not be fair to all the other Army couples that duty had separated. The Eisenhowers had to settle for a few days together in Washington in June 1945. Not until the end of the year, when Eisenhower returned to the United States to succeed Marshall as Army chief of staff, were they finally reunited.

Those years were lonely and difficult, especially because of rumors that Eisenhower developed a romantic relationship with Kay Summersby. The British assigned Summersby as Eisenhower's driver in 1942, and she remained on his staff throughout the war. She was attractive and engaging, and she sometimes appeared in photographs with Eisenhower that Mamie would see in the newspapers. Eisenhower enjoyed her company, but he wrote frequently to Mamie that he wanted nothing more than to be together with her again.

Soon after the war, Summersby wrote a book in which she said that she had a strong but platonic relationship with her wartime boss. A quarter-century later, as she was dying of cancer, she wrote a second book, Past Forgetting, in which she claimed that she and Eisenhower had had a love affair. No other member of Eisenhower's wartime staff ever provided confirmation of Summersby's assertions.

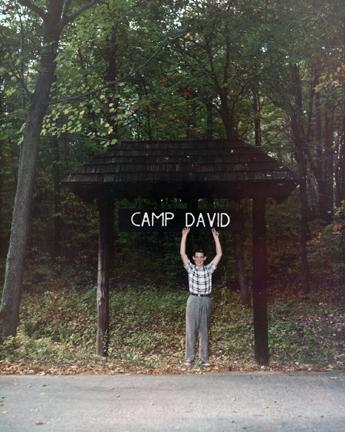

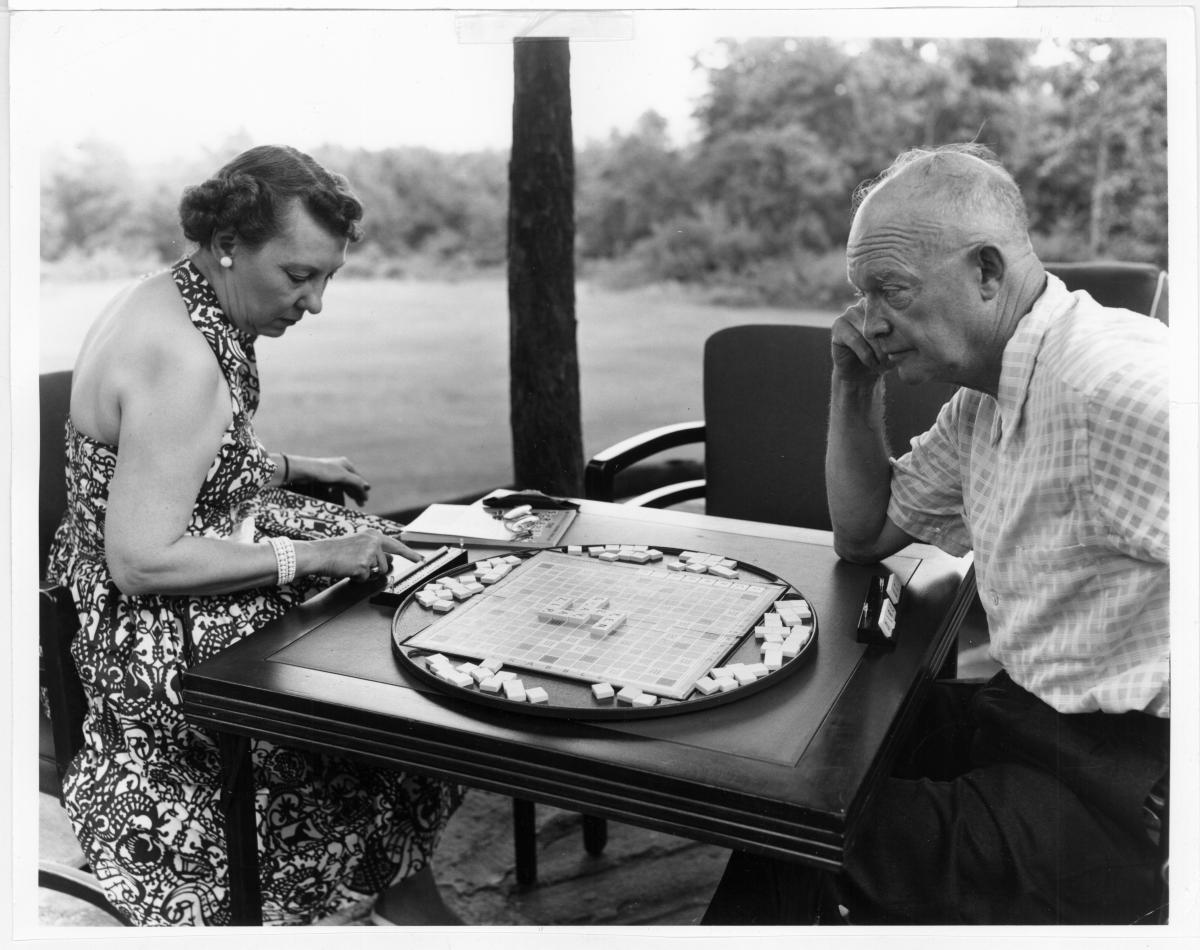

Like millions of other Americans, the Eisenhowers overcame the strains of war by being together again. They still moved frequently—Washington, New York, and Paris—but finally enjoyed the luxury of eight years in one home—the White House. Duty once again competed with family time, but at least grandchildren were nearby after John became an aide to his father in 1958. Family life even altered official life in a small but enduring way. After the remodeling of the presidential retreat in the Maryland mountains that Franklin D. Roosevelt had called Shangri-La, Eisenhower renamed it after his grandson—Camp David.

Eisenhower also enjoyed the company of a group of friends that he called "the gang." Most of the eight or nine members of "the gang" were wealthy business leaders who liked spending time with the President and making it easy for him to relax. They joined him on fishing trips to Colorado or golfing vacations to Georgia, and they came to the White House for evenings of conversation and bridge. They provided him with gifts, even helping to pay for the construction of the Eisenhower Cabin at the Augusta National Golf Club.

Sometimes Mamie joined the President on social occasions with "the gang" and their wives, but since she disliked exercise, Eisenhower often found enjoyment in what he called "stag" events, recreation that involved just him and his male companions.

Retirement provided the Eisenhowers with more time than ever before to spend together. They enjoyed those years on their Gettysburg farm as well as the travels that took them to many places in the United States and overseas. Eisenhower remained active in public life until ill health restricted his activities in the final year before his death in March 1969. But during their last eight years together, Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower at last had all the time they desired for family life.

Dwight D. Eisenhower was older than any previous President, leaving office at the age of 70. Yet the Eisenhower years are remembered not because there was a grandfather in the White House but because there were so many children in millions of American homes. Eisenhower was President during the baby boom, a time of rapid population growth that lasted from 1946 through 1964. The baby boom reached its peak in the mid-1950s, with more than 4 million births each year.

Family Life During the Baby Boom

What accounted for the rapid growth in population was that men and women who came of age during and after the Second World War married in record numbers. They also married very early in adulthood. The median age at which women married for the first time during the 1950s was just over 20 years old. For men, the age was between 22 and 23. Some of these couples had large families, with four or five children or more, but most had two or three children. They usually had them soon after marrying, and there was often only a short interval between the time that the first baby was born and the second or third baby arrived. A record rate of marriage for young adults, who then had children quickly, made for the baby boom.

Young people chose to marry early and have children. They expected that home and family would provide happiness, fulfillment, and security. The pleasures of domestic life were especially appealing in the 1950s since depression and war had prevented people from forming families in the 1930s and 1940s.

During the 1950s, women faced pressures to marry and to give first priority to domestic responsibilities. Although women attended college in record numbers during this decade, opportunities for careers after graduation were limited. Some employers said that they did not want to hire women because they expected them to quit their jobs once they married and had children. Contemporary commentators sometimes said that women went to college to earn an "Mrs." Degree—to meet the right man and marry. Women who hoped that college would prepare them for careers could get contrary advice. Adlai Stevenson, the two-time Democratic nominee for President, told the female graduates at Smith College that they could best serve society "in that humble role of housewife. I could wish you no better vocation than that."

For middle-class women, marriage and motherhood often brought a home in the suburbs, which were frequently enclaves of young white families. By 1960, almost as many Americans lived in suburbs as in central cities; during the next decade, more people would reside in suburbs than cities.

Many of those suburban wives held jobs outside the home. By 1960, 38 percent of all women over age 16 worked outside the home. Fifty-five percent of those female workers were married. Some were middle-class mothers who worked to raise the family income; others were heads of household, who provided the only source of income. In 1960, women were the heads of household in 10 percent of families. Many of these women worked in low-paying, sex-segregated jobs as clerks, secretaries, and telephone operators. Nursing and teaching were among the few professions in which substantial numbers of women could hope to find jobs.

Change and Continuity

In the 1950s, the American people were on the move. Often they went west, especially to California. The population of the United States increased by more than 18 percent during the 1950s. There were 48 percent more Californians in 1960 than there had been a decade earlier, and neighboring Nevada and Arizona enjoyed gains of 78 and 73 percent, respectively. New York, then the largest state, gained only 13 percent. Some people, especially African Americans, moved north into midwestern or eastern cities, leaving the rural South, where new farm technology had limited opportunities for employment.

For some Americans, migration meant a chance to start anew, an opportunity to prosper. For African Americans and American Indians, moving to cities frequently meant a different kind of poverty or new forms of discrimination. Yet African Americans who moved north did gain a chance to vote, a basic right usually denied them in the South. During the 1950s, most southern states used a variety of methods, including literacy tests and poll taxes, to keep most African Americans out of voting booths. But in northern cities, such as Chicago, New York, and Detroit, African American voters became a powerful political force.

For a Republican, Eisenhower did well among African American voters, who had supported Democratic presidential candidates since the 1930s. He also showed some strength in what had been the Democratic Solid South. In both 1952 and 1956, Stevenson won the six adjacent states from Arkansas to North Carolina. But in 1956, Eisenhower carried Louisiana; he was the first Republican to do so since the end of Reconstruction. Eisenhower's victory in that state was an early indication of a change that was just beginning, as the South shifted toward the Republican Party during the next two decades.

Dwight D. Eisenhower's reputation among historians has changed dramatically in the last five decades. A poll of prominent historians in 1962 placed Eisenhower 22nd among Presidents, a barely average chief executive who was as successful as Chester A. Arthur and a notch better than Andrew Johnson. Two decades later, his ranking had moved up to 11th, and by 1994, he placed 8th, the same position he held in a C-SPAN poll of presidential historians in 2009. Among Presidents who held office in the last 75 years, he ranked behind only Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman.

Eisenhower's reputation has changed as more records and papers have become available to study his presidency. Contemporaries remembered Eisenhower's frequent golfing and fishing trips and wondered whether he was leaving most of the business of government to White House assistants. They also listened to his meandering, garbled answers to questions at press conferences and wondered whether he grasped issues and had clear ideas about how to deal with them. Previously closed records that started to become available at the Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kansas, in the 1970s revealed that the President had thoughtful views about most major issues and frequently took an active role in discussing them with the cabinet or at meetings of the National Security Council. Historians now appreciate that Eisenhower recognized the political advantages of working behind the scenes to deal with controversial issues, using his "hidden hand" to guide policy while allowing subordinates to take any credit—as well as the political heat.

While critics in the 1950s scorned Eisenhower as a "do-nothing" President, historians in the 21st century sometimes praise him for not taking action. Eisenhower did not lead the country into war, although he might have chosen to do so in Indochina in 1954. He negotiated an armistice in the Korean War only six months after taking office. For the rest of his presidency, peace prevailed, even if at times Cold War tensions were high. Eisenhower also did not adopt policies that jeopardized the strong economic growth during the 1950s, and he made decisions that stimulated the economy, such as supporting the construction of the Interstate Highway System. Although national security spending was high during the Eisenhower years, the President did not give in to temptations to spend even more. After the Soviets launched the world's first artificial satellite, Sputnik, on October 4, 1957, Eisenhower resisted panicked public demands for huge increases in military spending since he knew that the nation's defenses remained strong. He insisted that he would not spend one penny less than was necessary to maintain national security—nor one penny more.

Although Eisenhower now gets credit he deserves for preserving peace and prosperity, historians have not overlooked the limit of his achievements. His "hidden hand" eventually helped push Senator Joseph R. McCarthy out of the national spotlight, but Eisenhower's unwillingness to confront McCarthy directly allowed the senator to continue to abuse his power and sully the reputations of those he wrongfully accused. Despite some significant actions to advance civil rights, Eisenhower remained a gradualist who firmly believed that changes in individual hearts and minds more than the passage of laws would eliminate racial barriers. Despite this conviction, Eisenhower did not try to change contemporary thinking about racial issues by speaking out in favor of civil rights. He did take actions to end racial segregation, but he was unwilling to use his moral authority as President to advance the most important movement for social justice of the 20th century.

Although he avoided war, Eisenhower did not achieve the peace he desired. He hoped for détente with the Soviet Union but instead left to his successor an intensified Cold War. He was unable to secure a test-ban treaty, which he hoped would be an important part of his legacy. The covert interventions he authorized in Iran and Guatemala yielded short-term success but contributed to long-term instability.

Eisenhower, in short, achieved both important successes, but he sometimes fell short of his most cherished objectives. He left office a popular President, and his stature has grown with the passage of time.

John F. Kennedy was born into a rich, politically connected Boston family of Irish-Catholics. He and his eight siblings enjoyed a privileged childhood of elite private schools, sailboats, servants, and summer homes. During his childhood and youth, “Jack” Kennedy suffered frequent serious illnesses. Nevertheless, he strove to make his own way, writing a best-selling book while still in college at Harvard University and volunteering for hazardous combat duty in the Pacific during World War II. Kennedy's wartime service made him a hero. After a short stint as a journalist, Kennedy entered politics, serving in the US House of Representatives from 1947 to 1953 and the US Senate from 1953 to 1961.

Kennedy was the youngest person elected US president and the first Roman Catholic to serve in that office. For many observers, his presidency came to represent the ascendance of youthful idealism in the aftermath of World War II. The promise of this energetic and telegenic leader was not to be fulfilled, as he was assassinated near the end of his third year in office. For many Americans, the public murder of President Kennedy remains one of the most traumatic events in memory; countless Americans can remember exactly where they were when they heard that President Kennedy had been shot. His shocking death stood at the forefront of a period of political and social instability in the country and the world.

Born soon after America's entry into the First World War, John Fitzgerald Kennedy was the nation's first president born in the 20th century. Both parents hailed from wealthy Boston families with long political histories. His maternal grandfather had been mayor of Boston. Kennedy's father, Joseph P. Kennedy, had made a fortune in the stock market, entertainment, and other business, managing to take his money out of the stock market just before the crash of 1929. Though the ensuing Great Depression gripped the nation, “Jack” and his eight siblings enjoyed a privileged childhood of elite private schools, sailboats, servants, and summer homes. Kennedy later claimed that his only experience of the Great Depression came from what he read in books while attending Harvard University.

For John, this privileged childhood was interrupted repeatedly by chronic bouts of illness. Afflicted with an almost constant stream of ailments, several of which went undiagnosed, Kennedy spent much of his time recuperating.

In 1938, on the eve of the Second World War, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Joseph P. Kennedy, John's father, to the key post of ambassador to the United Kingdom. The new ambassador was unsympathetic to British preparedness policies and found a cool reception in London. That year, Jack inherited $1 million dollars from his family, but his ambition remained strong. While in England with his father, he wrote his senior essay for Harvard University on England's lack of readiness for the Second World War. It was published and was well received by critics, becoming a bestseller under the title, Why England Slept.

World War II Military Service

After Kennedy graduated from Harvard, the United States entered World War II. His efforts to join the US Navy were initially thwarted by his ill-health, but after his father invervened, he was eventually admitted and assigned to serve in the South Pacific, commanding a small motor-torpedo boat, or “PT boat.” Kennedy and his crew participated in the campaign to wrest thousands of islands from Japanese control.

In August 1943, as the sailors were sleeping without posting a watch (in violation of naval regulations), a Japanese destroyer rammed his boat, PT 109. Towing a badly burned crewmate by a life-jacket strap clenched in his teeth, Kennedy led the crew's ten survivors on a three-mile swim to refuge on a tiny island. The crew hid on the island from the enemy for days until Kennedy managed to summon help.

Widely credited with the rescue of his crew, Kennedy received the US Navy and Marine Corps Medal for Valor and a Purple Heart for injuries he sustained. Nevertheless, he returned home to a naval inquiry on the sinking. Although a board found evidence of poor seamanship, the Navy needed heroes more than it needed scapegoats, and Kennedy was cast as the former to build public morale, and recruited to go on speaking tours.

The war ended in 1945, but not without a deep cost to the Kennedy family: the oldest son, Joseph Jr., a pilot, was killed on a bombing mission in Europe. Handsome and outgoing, Joseph had been the one tapped by his father to become president one day. Upon his death, his father's aspirations fell on John.

The Political Climb

After being discharged from the Navy, John Kennedy worked briefly as a reporter for the Hearst newspapers, and in 1946, the twenty-nine-year-old Kennedy won election to the US Congress representing a working-class Boston district. He served three terms in the US House of Representatives, earning a reputation as a somewhat conservative Democrat. He was re-elected in 1948 and again in 1950. In 1952, he ran for the US Senate and defeated the Republican incumbent from another Massachusetts family with a long political history, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. That same year, he met Jacqueline Bouvier at a dinner party, and, as he later put it, “leaned across the asparagus and asked her for a date.” The two were married a year later and had three children, one of whom died in infancy in August 1963.

Kennedy continued to be dogged by poor health. Left thin and sallow by malaria brought home from the war in the Pacific, he also suffered from Addison's disease, which many doctors considered terminal. He relied on a steady stream of painkillers and steroids to treat the symptoms of his many ailments. Constant back pain prevented him from lifting even his own small children. Ironically, though, Kennedy's public image was one of youth, health, and vigor.

Kennedy put one period of enforced convalescence from back surgery to productive use by writing Profiles in Courage, a book about eight American senators who had taken unpopular but admirable moral stands. Benefiting also from the handiwork of Senate staffer Theodore Sorensen, the book won the Pulitzer Prize for biography in 1957.

Due to his continuing poor health, Kennedy had one of the worst attendance records in Congress. His real achievements in the Senate were few, but almost immediately after election he began angling for even higher office. In 1956, he mounted a serious quest for the vice presidential spot alongside presidential hopeful Adlai Stevenson. He narrowly lost the bid to Estes Kefauver, a senator from Tennessee.

Ultimately, though, this defeat proved a blessing. The Republican incumbents, President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Vice President Richard M. Nixon, soundly beat Stevenson and Kefauver that fall; neither Democrat would ever be a real contender for the office again. Kennedy, however, remained untarnished by Stevenson's defeat, and the exposure he got at the 1956 national Democratic convention made him a serious contender for the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination.

Reelected to the Senate in 1958, Kennedy became a member of its influential Foreign Relations Committee, which he used as a platform to attack President Eisenhower's diplomatic and military policies, claiming that the United States was on the wrong side of a “missile gap” with the Soviet Union. Kennedy continued to press these themes as he began maneuvering to get the Democratic nomination for the 1960 presidential election.

By Jessica Ferrell and David Coleman

In anticipation of someday writing his memoirs, John F. Kennedy periodically dictated notes on recent developments or on other issues he might one day want to include in the book.

Although he had not yet won the presidency--"the ultimate source of action," as he called it--when he made this recording, probably in the fall 1960 during the height of the presidential campaign, Kennedy reflected on his political career up to that point and his philosophy of politics in national service.

Date: Fall 1960

Participants: John F. Kennedy

The Campaign and Election of 1960

The election of 1960 brought to the forefront a generation of politicians born in the twentieth century, pitting the 47-year-old Republican vice president Richard M. Nixon against the 43-year-old Democratic challenger John F. Kennedy.

Kennedy's chief rival for the nomination was Hubert H. Humphrey from Minnesota, whose steadfast liberalism played well with many in the Midwest. The two fought it out in thirteen primaries. Humphrey's best hope rested on winning in his “back yard” of neighboring Wisconsin, and then painting himself as the new favorite. But Kennedy's superior planning, financing, and political instincts won out, and he beat Humphrey in his own region.

The nomination's turning point occurred in the West Virginia primary. A working-class, heavily Protestant state, West Virginia was critical for Kennedy, who had to show that a wealthy Catholic was electable there. Humphrey desperately threw all his remaining resources into the fray, even tapping a savings fund for his daughter's upcoming wedding. But the Kennedy machine overwhelmed him with money and savvy. In West Virginia, the only state in which it was legal for a campaign to pay workers and voters money for showing up at the polls, Kennedy's financing gave him a distinct advantage. Dispirited and broke, Humphrey abandoned the race.

At the Democratic National Convention held in Los Angeles in early July, Kennedy defeated his nearest rival, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, the Senate majority leader, on the first ballot. Kennedy then invited Johnson to become his running mate, a controversial move made ostensibly to placate the South, bypassing other party leaders such as Humphrey and Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri. In his acceptance speech, Kennedy pledged to “get the country moving again.” Americans, he said, stood “on the edge of New Frontier—of the 1960s—a frontier of unknown opportunities and perils—a frontier of unfilled hopes and threats.”

The Republicans, meeting a few weeks later in Chicago, nominated Nixon, making him the first vice president in the history of the modern two-party system to win the presidential nomination in his own right. Nixon chose Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the chief US delegate to the United Nations, as his running mate.

Once he had won the nomination of his party, Kennedy undertook the task of convincing American voters that he would make a better president than his rival. Kennedy cast himself as a Cold War liberal and promised to lead America out of what he called the “conservative rut” into which he accused Eisenhower, and by implication Nixon, of running the country. It was apparent throughout the campaign that the election would be close. A Gallup poll in late August put Nixon and Kennedy tied at 47 percent each, with 6 percent undecided.

Kennedy faced two great hurdles in his quest for the White House: his youth and his religion. Polls revealed that many Americans balked at the prospect of such a young man, untested on the world stage, leading the nation at a time of threatening Cold War peril, especially after Dwight Eisenhower, who projected a comforting grandfatherly image. For Nixon, although he was only four years older than Kennedy, this issue was less acute since he had the advantage of having served as vice president for the duration of Eisenhower's two terms and was therefore a more familiar face.

Even more unsettling to many Protestants was the prospect of a Roman Catholic, whom the Catholic Church might “control,” as the nation's president. Kennedy chose to tackle the religious issue openly and directly, giving a series of speeches designed to address any misgivings about his faith and voluntarily subjecting himself to a round of questioning about his views on church-state relations by leading Protestant clergy in Houston. The group's conclusion that they were satisfied with his answers provided a degree of comfort for many non-Catholic voters.

Televised Debates

In order to overcome Nixon's advantage in public recognition, Kennedy challenged Nixon to a series of televised debates. Nixon, an experienced debater, accepted. The series of debates between the two candidates became the first extensive use of what would thereafter become a staple medium of American political campaigns—television. Broadcast live on national television in late September and early October, the four debates ultimately provided the Kennedy campaign with a huge boost.

Seventy million people watched the first debate. The Richard Nixon that viewers saw on their black-and-white television sets appeared pallid, tense, and uncomfortable. Just out of the hospital for the treatment of an infected cut, he wore a light-colored suit that blended into the gray background; in combination with the harsh studio lighting that left Nixon perspiring, he offered a less-than commanding presence. By contrast, Kennedy appeared relaxed, tanned, and telegenic.

A mythology has taken root about post-debate opinion polls and their revelations about popular perceptions of the two candidates. Allegedly, those who had listened to the debates on the radio thought that Nixon had won, with the larger television audience being generally more impressed with Kennedy. No such comparative polls exist, however, and the market research on which those conclusions rest incorporated too few radio listeners to be statistically valid.

Both candidates traveled extensively and spent freely. Nixon, however, was hamstrung by an unfortunate early pledge to campaign in every state of the union. The trips to vote-poor states took precious time and money, while Kennedy focused his resources and time on the states with the most electoral college votes.

On Election Day, November 8, Kennedy won the popular vote by less than 120,000 votes out of a record 68.8 million ballots cast. Kennedy won the electoral college vote more clearly, winning 303 votes to Nixon's 219 (with Virginia's Harry F. Byrd winning 15). The closeness of the election naturally fueled speculation of tampering on both sides. In Chicago, Democratic mayor Richard Daley delivered an unusually good result for Kennedy—a result that came under scrutiny when Kennedy won Illinois by less than 9,000 votes. Citing voting irregularities, the Republican National Committee unsuccessfully challenged the Illinois vote in federal court, although Nixon carefully distanced himself from the various legal challenges presented by his party and his supporters. Suspicious results also emerged in Texas and elsewhere. Kennedy was initially believed to have won California, but after absentee ballots had been counted, that state's electors declared for Nixon.

Inauguration and Transition

On a cold January 20, 1961, John F. Kennedy took the oath of office. After such a close campaign, Kennedy knew his inaugural address would have to reach out to his opponents. In the days and weeks before it was to be delivered, he carefully studied famous American speeches, such as the Gettysburg Address, and copied their terse, vivid style. Departing from the pattern of many inaugural addresses, Kennedy pulled few punches and focused almost exclusively on matters outside the nation's borders. In addition, he claimed that his election signaled a fundamental generational shift in America:

“We observe today not a victory of party, but a celebration of freedom—symbolizing an end, as well as a beginning—signifying renewal, as well as change . . . Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage—and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this Nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world.”

And he recalled the nation's revolutionary origins: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear in burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty.” In forming his administration, Kennedy surrounded himself with liberal intellectuals and, in light of the close popular vote, moderate conservatives espousing strong executive governance, rational planning, and a belief in the virtues of social science. An elite group of young, rich professionals, dubbed the “New Frontiersmen,” poured into Washington, adding to the tone of a White House seeking counsel from the nation's best and brightest.

The Miller Center celebrated the 100th anniversary of the birth of John F. Kennedy with special guest Thomas Oliphant, former Boston Globe reporter and writer.

His new book with co-author Curtis Wilkie, The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, begins with a health scare. In 1955, Eisenhower’s heart attack changed the mindset of people like Richard Nixon and JFK. They came to realize the great war hero was mortal. JFK sensed an opportunity. As the authors argue, “The force behind Kennedy’s ambition was Kennedy himself,” not his father, as is often reported.

History books also tend to begin the story of Kennedy’s 1960 election with his efforts to become Adlai Stevenson’s running mate in 1956. The Road to Camelot, however, takes a different tack. One of JFK’s legacies, it explains, was his masterful use of grassroots campaigning to bypass the Democratic Party system, clinching him the nomination. This primary fight was not easy, and it was not predetermined.

In the video below, Oliphant discusses his new book with two of the Miller Center's Kennedy scholars, Barbara Perry and Marc Selverstone.

Kennedy's domestic agenda, outlined in his “New Frontier” acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention in July 1960, faced a difficult passage through Congress. The president was unable to call on the Democratic majority in Congress to support his most progressive legislative reforms, and many Southerners in his own party—several of whom chaired its most powerful committees—were suspicious of Kennedy, his northeast establishment background, and his domestic priorities. Time and again, Kennedy thought he had little choice but to compromise on his legislative program.

Economic and Legislative Challenges

Kennedy took office in the depths of the fourth major recession since World War II. Business bankruptcies had reached their highest level since the 1930s, farm incomes had decreased 25 percent since 1951, and 5.5 million Americans were looking for work. To stimulate the economy, Kennedy pursued legislation to lower taxes, protect the unemployed, increase the minimum wage, and energize the business and housing sectors. Kennedy believed these measures would launch an economic boom that would last until the late 1960s.

His advisers thought it possible to “fine tune” the economy through fiscal and monetary adjustments. Kennedy accepted their advice and was impressed with their expertise, which seemed to bear fruit. Partly as a result of the administration's efforts to pump money into domestic and military spending, the recession faded by the end of Kennedy's first year in office. The president also proposed new social programs including federal aid to education, medical care for the elderly, urban mass transit, a Department of Urban Affairs, and regional development in Appalachia.

Lacking deep congressional support, however, Kennedy's programs encountered resistance. He did manage an increase in the minimum wage, but a major medical program for the elderly went nowhere. Attempts to cut taxes and broaden civil rights were watered down on Capitol Hill. Southern Democrats killed the proposal for a Department of Urban Affairs because they thought Kennedy would appoint an African American as its first secretary. The education bill foundered on the question of aid to parochial schools; Kennedy, as a Catholic, opposed such aid to maintain his credibility with the electorate. His successor as president—a Protestant—was under no such constraints and would pass a bill providing aid for parochial education. On the positive side of the ledger, the government undertook regional development in Appalachia, an initiative that would have a major impact over the next three decades in reducing poverty in the region.

Civil Rights

But by far the most volatile—and divisive—domestic issue of the day was civil rights. African Americans were striving to reverse centuries of social and economic hardship, and activism against legalized racism was growing. This activism was troubling to many whites, particularly in the South. Kennedy's role—or lack of it—in this great crusade remains controversial. In short, he concentrated more on enforcing existing civil rights laws than on passing new ones.

Moreover, the president had to bow to the custom of “senatorial courtesy” and appoint federal judges in the South who were acceptable to Southern Democratic senators. These judges were opposed to civil rights enforcement, and their record was much worse than that of judges appointed in the South by President Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican who was under no such party constraints. On several occasions, Kennedy invoked some of the highest powers of his office to send troops to Southern states that were refusing the racial integration of their schools.

In September 1962, a long-running effort by James Meredith, a black Mississippian and veteran of eight years in the US Air Force, to enroll at the traditionally white University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) came to head. When Governor Ross Barnett of Mississippi defied federal court rulings allowing Meredith to enroll at the university, Kennedy, through his brother Robert, the attorney general, federalized the Mississippi National Guard and ordered an escort of federal marshals to accompany Meredith to the campus. Meredith finally enrolled on October 1, 1962, but not without a violent riot that took thousands of guardsmen and armed soldiers fifteen hours to quell. Hundreds were injured, and two died.

During 1963, the civil rights struggle grew increasingly intense and occasioned increasing violence. Images of black citizens, including children, being attacked by dogs and hosed down by water canons in Birmingham, Alabama, shocked Americans. For their part, African American activists, alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., proclaimed their impatience with “tokenism and gradualism . . . We can't wait any longer.” From the persistence of the Freedom Riders in 1961 seeking to desegregate buses in the South—in the face of great personal peril—to the huge “March on Washington” in August 1963 at which King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech to an audience of a quarter of a million people, it was clear that the civil rights movement was not going to fade away and was, in fact, galvanizing. And when four children were killed that September in a racially motivated bombing of a church in Birmingham, Alabama, Kennedy once again chose to intervene.

Kennedy's political strategy had been to delay sending a civil rights bill to Congress until his second term, when he could afford to split his party and pick up the backing of moderate Republicans to pass the measure. He felt that if he pursued such legislation in his first term, the rest of his program would suffer. However, African Americans remained frustrated by the political maneuvering and insisted on immediate action to protect their rights. Following the June 11, 1963, confrontation with Alabama governor George C. Wallace over the integration of that state’s flagship university, as well as the murder of Mississippi NAACP field director Medgar Evers early the next morning, Kennedy submitted a civil rights bill to Congress, which became law after his death. In a televised speech announcing his decision, he observed that the grandchildren of the slaves freed by Lincoln “are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice.”

Once in office, it was clear that Kennedy would likely face several international challenges that could come from any number of directions. Recurring flare-ups in Berlin, periodic crises with Communist China, and an increasingly vexing situation in Southeast Asia, all threatened to erupt.

The Bay of Pigs

It was Cuba, however, that was the site of an immediate crisis, largely of the administration's own making. Kennedy had only been in office two months when he ordered the implementation of a covert CIA plan inherited from the Eisenhower administration—which he altered dramatically—to topple Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Assured by military advisers and the CIA that its prospects for success were good, Kennedy gave the green light. In the early hours of April 17, 1961, approximately 1,500 anti-Castro Cuban refugees landed at Bahia de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) on Cuba's southern coast. A series of crucial assumptions built into the plan proved false, and Castro's forces quickly overwhelmed the refugee force. Moreover, the Kennedy administration's cover story collapsed immediately. It soon became clear that despite the president's denial of US involvement in the attempted coup, Washington was indeed behind it. The misadventure cost Kennedy dearly. Yet his administration continued to press for Castro’s ouster, launching the CIA-backed Operation Mongoose in November 1961 to harass and destabilize the Cuban regime.

Vienna and Berlin

Still recovering from this humiliating political defeat, Kennedy met with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna in June 1961. Khrushchev renewed his threat to “solve” the long-running Berlin problem unilaterally, an announcement that in turn forced Kennedy to renew his pledge to respond to such a move with every means at his disposal, including nuclear weapons. In a dramatic move two months later, in mid-August 1961, the Soviets and East Germans constructed a wall separating East and West Berlin, providing the Cold War with its most tangible incarnation of the Iron Curtain.

Missiles in Cuba

By the fall of 1962, Cuba again took center-stage in the Cold War. In an effort to protect the Castro government, compete with China for the hearts of revolutionaries worldwide, and neutralize the massive American advantage in nuclear weapons—particularly as part of any new Berlin gambit—Khrushchev ordered a secret deployment of long-range nuclear missiles to Cuba along with a force of 42,000 Soviet troops and other associated conventional and atomic weaponry. For months, despite close American scrutiny, the Soviets managed to keep hidden the full extent of the buildup. But in mid-October, US aerial reconnaissance detected the deployment of Soviet ballistic nuclear missiles in Cuba which could reach most of the continental United States within a matter of minutes.

By the fall of 1962, Cuba again took center-stage in the Cold War. In an effort to protect the Castro government, compete with China for the hearts of revolutionaries worldwide, and neutralize the massive American advantage in nuclear weapons—particularly as part of any new Berlin gambit—Khrushchev ordered a secret deployment of long-range nuclear missiles to Cuba along with a force of 42,000 Soviet troops and other associated conventional and atomic weaponry. For months, despite close American scrutiny, the Soviets managed to keep hidden the full extent of the buildup. But in mid-October, US aerial reconnaissance detected the deployment of Soviet ballistic nuclear missiles in Cuba which could reach most of the continental United States within a matter of minutes.

Kennedy consulted with his top advisers over a period of several days. These meetings, conducted by the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or ExComm, took place in utmost secrecy in order to maximize the range of available responses. Among the options considered were air strikes on the missile bases, a full-scale invasion of Cuba, and a naval blockade of the island. Kennedy eventually chose a blockade, or quarantine, of Cuba, backed up by the threat of imminent military action. In announcing his decision on national television on October 22, 1962—breaking the extraordinary secrecy surrounding the crisis to that point—Kennedy warned that the purpose of the Soviet missiles in Cuba could be “none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere” and that he would protect the United States from such a threat no matter what the cost. The lines, suddenly, were drawn very firmly indeed, and the world held its breath.

After several days of action and reaction, each seeming to bring the world closer to the brink of nuclear war, the two sides reached a deal. Khrushchev would order the withdrawal of offensive missiles, and Kennedy would promise not to invade Cuba; Kennedy also secretly promised to withdraw American ballistic nuclear missiles based in Turkey targeting the Soviet Union. Difficult negotiations aimed at finalizing the deal and verifying its implementation dragged on for several weeks but, on November 20, 1962, Kennedy finally ordered the lifting of the naval blockade of Cuba.

To the Moon

Kennedy was also instrumental in the success of the nation's space program. An enthusiastic proponent of it in public, if dubious of its more scientific dimensions in private, he vowed to have Americans on the moon by the end of the decade. Although the rockets would be launched from Cape Canaveral in Florida, Kennedy agreed to locate the headquarters of the Manned Spacecraft Center in Texas, the home state of his vice president; Lyndon Johnson had previously been head of the Senate subcommittee in charge of funding the space program. Kennedy would not live to see the landing of a man on the moon in July 1969.

The Developing World

President Kennedy created the Peace Corps by executive order in 1961, a reaction to both the growing spirit of activism throughout the West and Communist efforts to capitalize on the decolonization process. Through the promotion of modernization and development, Peace Corps volunteers sought to improve social and economic conditions throughout the world; their work also supported Kennedy’s efforts in the Cold War battle for hearts and minds. In September 1961, shortly after Congress formally endorsed the Peace Corps by making it a permanent program, the first volunteers went abroad to teach English in Ghana. Contingents of aid workers soon followed to Tanzania and India. The program proved enduring; by the end of the twentieth century, the Peace Corps had sent more than 170,000 American volunteers to over 135 nations.

Fears that Castro’s example might inspire Communist revolution throughout Latin America led Kennedy to offer a more specific program for hemispheric reform. The Alliance for Progress, announced in March 1961, comprised a series of measures to improve the region's social and economic fortunes. This charter—and the US financial aid that came with it—sought to improve America's standing in the region, though few Latin nations agreed with the US embargo on Cuba or cooperated with it.

Southeast Asia

Although Laos presented Kennedy with an initial (and recurring) challenge in the region, by the end of his presidency it was Vietnam that proved at least as difficult, and potentially more dangerous. America had been sending military advisers to Saigon since the early 1950s to help France in its war against Vietnamese Communists for control of the nation. In 1961, Kennedy increased this allotment and ordered in the Special Forces, an elite army unit, to train the South Vietnamese in counter-insurgency warfare. But war continued to spread, and by the end of Kennedy's presidency, 16,000 American military advisers were serving in Vietnam.

As with other aspects of his administration, it is not clear how Kennedy would have handled America's growing commitment to Vietnam had he lived out his term in office. Kennedy had announced plans in 1963 to reduce the number of American advisers, but this did not necessarily mean a reduction in the US commitment. The announcement was one of several measures designed to pressure Saigon into making reforms. Instead, the regime of President Ngo Dinh Diem continued its repression of political opponents. Diem was assassinated in November 1963 in a military coup, an act that perpetuated, and arguably exacerbated, the country’s political instability.

Limiting Nuclear Testing

Just months before his death, Kennedy secured an agreement, with Britain and the Soviet Union, to limit the testing of nuclear weapons in space, underwater, and in the earth's atmosphere. Not only did it seek to reduce hazardous nuclear “fallout,” it also signaled the success of Kennedy's efforts to engage the Soviet Union in constructive negotiations and reduce Cold War tensions, a goal captured most famously in his June 1963 remarks at American University. In the wake of the close call over Cuba, Kennedy considered this agreement his greatest accomplishment as president.

On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy and the First Lady journeyed to Dallas on a campaign trip. Accompanying the Kennedys in the motorcade through the city were Democratic governor John Connally and his wife, Nellie. As it moved through Dealey Plaza, gun shots rang out. Governor Connally was hit; President Kennedy who was shot twice, was mortally wounded. Kennedy was rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital, where he died soon thereafter.

The shots had been fired from a nearby warehouse, and some hours after the assassination, police arrested warehouse employee Lee Harvey Oswald. Oswald was a mysterious former Marine who had defected to the Soviet Union but then returned to the United States. Two days after the arrest, while being transferred to another jail, the suspect was himself slain by Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub owner. Ruby was tried and convicted of murder in Oswald's death. He died of cancer in January 1967, while awaiting a retrial in prison.

The dramatic course of events led many to wonder whether a conspiracy was afoot. A commission to investigate the assassination, established by President Lyndon B. Johnson and headed by Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, determined that Oswald had acted alone. In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded that there were at least three shots fired, although it drew no other firm conclusions. Although it concluded that two of Oswald’s three shots hit Kennedy, it also suspected that Kennedy “was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy.” Its findings did little to dispell conspiracy theories about Kennedy's assassination that have remained an enduring phenomenon.

On November 24, 1963, hundreds of thousands of people filed pass Kennedy's coffin in the rotunda of the Capitol. Kennedy was buried the next day, in a state funeral at Arlington Cemetery. Representatives from ninety-two nations attended the services, and an estimated one million people lined the streets of Washington, DC, to observe the funeral procession. For many Americans, the murder of John F. Kennedy would remain one of the most wrenching public events of their lives.

John and Jacqueline Kennedy had their first child, Caroline, in 1957; John Jr. was born two weeks after his father won the presidency. A third child, Patrick, died two days after his birth in August 1963. After a long succession of elderly presidents, it was refreshing for many to see the Kennedy family's youth and vitality. One image in particular stood out: that of John Jr. playing under the president's desk in the Oval Office. When JFK died, it was another image that would prove indelible: Jacqueline Kennedy whispering to John Jr. to be sure to give a military salute as the casket carrying the president passed by.

The president's extended family was large, wealthy, and powerful. President Kennedy named his brother Robert attorney general so, as he put it, his brother could “get some legal experience" before getting a job.” Congress was not amused by the joke, and although Robert served ably, it later passed a law forbidding the president to make appointments of close relatives to federal office. President Lyndon Johnson, seeing Robert as a rival, maneuvered to keep him off the Democratic ticket in 1964 by stating that no cabinet secretary would be considered. Robert responded wryly that he was sorry to take so many capable officeholders down with him.

In the November 1962 mid-term elections, John Kennedy's younger brother Edward (Teddy) successfully ran for the Senate seat JFK had vacated in Massachusetts. After the president's death, Robert Kennedy was elected as a senator from New York state and became a frontrunner for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968. This second Kennedy run for the White House was cut short by another assassin's bullet. After winning the California Democratic primary that June, Robert Kennedy was gunned down by Sirhan Sirhan. Edward Kennedy would also make a run for the Oval Office in 1980 when he unsuccessfully challenged President Jimmy Carter's renomination. Despite his defeat, Edward Kennedy remained an active and senior member of the US Senate until his death in 2009.