Dwight D. Eisenhower: Domestic Affairs

Although there were dangerous moments in the Cold War during the 1950s, people often remember the Eisenhower years as "happy days," a time when Americans did not have to worry about depression or war, as they had in the 1930s and 1940s, or difficult and divisive issues, as they did in the 1960s. Instead, Americans spent their time enjoying the benefits of a booming economy. Millions of families got their first television and their second car and enjoyed new pastimes like hula hoops or transistor radios. Young people went to drive-in movies or malt shops, often wearing the latest fashions—pegged pants for men, poodle skirts for women.

Yet the Eisenhower years were not so simple or carefree, and the President faced important and, at times, controversial issues in domestic affairs. Managing the economy involved important choices about how to maintain prosperity or how much to spend on what we today call "infrastructure." Protecting freedom and the rule of law necessitated difficult decisions as civil rights became an urgent national issue. Dealing with the effects of the Cold War at home required complicated action because of the sensational charges of Senator Joseph R. McCarthy about Communist infiltration of government agencies. In the eyes of a majority of the public, Eisenhower usually made the right choices, as he often enjoyed approval ratings of more than 70 percent in the polls. Yet Eisenhower also had critics, who believed that he had not used his powers as President vigorously or effectively to protect individual freedom and ensure justice.

[T]he Eisenhower years were not so simple or carefree

Modern Republicanism

During the campaign of 1952, Eisenhower criticized the statist or big government programs of Truman's Fair Deal, yet he did not share the extreme views of some Republican conservatives. These "Old Guard" Republicans talked about eliminating not just Fair Deal but also New Deal programs and rolling back government regulation of the economy. Eisenhower favored a more moderate course, one that he called Modern Republicanism, which preserved individual freedom and the market economy yet insured that government would provide necessary assistance to workers who had lost their jobs or to the ill or aged, who through no fault of their own, could not provide for themselves. He intended to lead the country "down the middle of the road between the unfettered power of concentrated wealth . . . and the unbridled power of statism or partisan interests."

As President, Eisenhower thought that government should provide some additional benefits to the American people. He signed legislation that expanded Social Security, increased the minimum wage, and created the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. He also supported government construction of low-income housing but favored more limited spending than had Truman.

Eisenhower secured congressional approval of some important new programs that improved the nation's infrastructure. In partnership with Canada, the United States built the St. Lawrence Seaway. His most ambitious domestic project, the Interstate Highway program, established in 1956, created a 41,000-mile road system. This highway project, which, as the President said, involved enough concrete to build "six sidewalks to the moon," stimulated the economy and made driving long distances faster and safer. Yet despite their many benefits, the new super highways also had adverse effects, as they encouraged the deterioration of central cities, with residents and businesses moving to outlying locations.

Eisenhower often got his way with Congress, especially during his first term. But in his last years as President, with Democrats in control of both the House and the Senate, Congress spent more for domestic programs than Eisenhower would have preferred. Although the President used his veto to block expensive programs, domestic spending still rose substantially, increasing from 31 percent of the budget in 1953 to 49 percent in 1961. Still, during the Eisenhower years, federal spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP)—a measure of the overall size of the U.S. economy—declined from 20.4 to 18.4 percent. During no presidency since Eisenhower’s has there been a decrease of any size in federal spending as a percentage of GDP.

Prosperity and Poverty

Although mild recessions slowed growth in 1953-1954, 1957-1958, and again in 1960, the economy expanded robustly during most of the 1950s. Unemployment was generally low, and inflation usually was 2 percent or less. Indeed, Eisenhower’s record of strong growth and low inflation was better than that of any other post-World War II President. Although Old Guard conservatives pressed Eisenhower to cut taxes, the President gave a higher priority to balancing the budget. Eisenhower had moderate success—three of his eight budgets were in the black. Wage earners enjoyed a prosperous decade: During the Eisenhower presidency, personal income increased by 45 percent. Many families used their purchasing power to buy new houses, frequently in suburban developments. Consumers also used their income to acquire many new household items, including television sets and high-fidelity equipment. A few families even made their purchases by using the first charge cards from Diners Club and American Express.

Still, many Americans did not share in the prosperity of the 1950s. About one in every five Americans lived in poverty by the end of the decade. The poverty rate declined during Eisenhower's presidency, but 40 million Americans were poor when Eisenhower left office. The South had almost half of the country's poor families. Yet during the 1950s, poverty increased in northern cities, partly because of the migration of African Americans who left the South for cities like Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland because new farm machines had taken away job opportunities. Often these new African American urban residents had to settle for low-paying employment because of job discrimination. Children and the elderly were much more likely to experience poverty than adults from ages 18 through 65.

Even though poverty was widespread, poor people got little attention during the 1950s. It was easier to celebrate the abundance of a booming consumer economy. People who had lived through the Great Depression of the 1930s emphasized the economic security of the 1950s. It was not until the 1960s that affluent Americans rediscovered the poverty amid the prosperity.

Eisenhower and McCarthy

One of Eisenhower's most difficult political problems involved Senator Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin, who had made headlines since 1950 because of his charges that Communist spies or sympathizers held high positions in the federal government. Republicans had gained from McCarthy's charges that the Truman administration was "soft on Communism." But after the Eisenhower administration took power, McCarthy continued his attacks, even suggesting that the President's nominees for important ambassador positions were disloyal or subversive. Republican leaders could not persuade McCarthy, a member of their own party, to halt his attacks on a Republican administration. The news media gave McCarthy significant attention, but his charges never led to a single indictment or conviction for espionage or treason.

Eisenhower also worried about Communist spies or agents, but he disliked McCarthy's outrageous methods, including a tendency to consider someone guilty until proven innocent. Eisenhower, however, did not want to criticize McCarthy publicly, as he was fearful that such a direct confrontation would demean his office or work to the senator's advantage: "I just won't get into a pissing contest with that skunk," the President declared.

In 1954, Americans got a good look at McCarthy in action when he held televised hearings on Communist influence in the U.S. Army. Eisenhower was outraged that McCarthy had made the Army—the institution in which the President had served for most of his adult life—a target. Nevertheless, he decided to work quietly, behind the scenes, to frustrate McCarthy's investigations. What did more to diminish the senator's power was television's ability to bring McCarthy's surliness into American living rooms. By 1954, 56 percent of American homes had television. Television could have a powerful political effect. Eisenhower used it to his advantage; he was the first President to allow television cameras in his news conferences and the first to have an advertising agency produce a television campaign commercial for his reelection. Television could also diminish political power, and that is what it did to McCarthy. After watching McCarthy on television, millions of viewers agreed with the question that Joseph Welch, a lawyer working for the Army, put to the senator: "Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last?"

At the end of 1954, the Senate voted to censure McCarthy. Never again was the senator a major force in national politics. During the four years that he had the spotlight, however, McCarthy ruined many reputations by making reckless and unsubstantiated charges. Eisenhower played a significant, albeit limited, role in finally curbing McCarthy's power.

Civil Rights

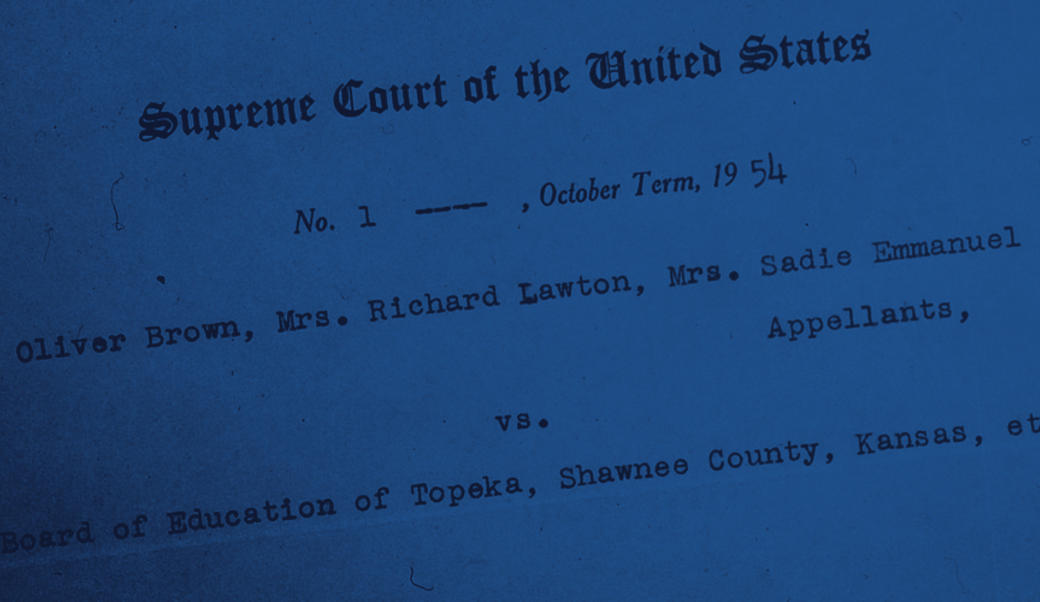

Eisenhower did not like dealing with racial issues, but he could not avoid such matters after the Supreme Court ruled in 1954 in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Eisenhower never spoke out in favor of the Court's ruling. Although the President usually avoided comment on court decisions, his silence may have encouraged resistance to school desegregation. In many parts of the South, white citizens' councils organized to prevent compliance with the Court's ruling. While some of these groups relied on political action, others used intimidation and violence.

Although Eisenhower did not endorse the Brown decision, he had a constitutional responsibility to uphold the Supreme Court’s rulings. He did so in 1957, when mobs prevented the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Governor Orval Faubus saw political advantages in using the National Guard to block the entry of the first African American students to Central High. After meeting with Eisenhower, Faubus promised to allow the students to enroll, but then he withdrew the National Guard, which allowed a violent mob to surround the school. Eisenhower dispatched federal troops and explained that he had a solemn obligation to enforce the law.

Eisenhower’s action was significant as it was the first time since Reconstruction that a President had sent military forces into the South to enforce federal law. In explaining his action, however, Eisenhower did not declare that desegregating public schools as the Supreme Court had ordered was the right thing to do. Instead, in a nationally televised address, he asserted that the violence in Little Rock was harming U.S. prestige and influence around the world and giving Communist propagandists an incident “to misrepresent our whole nation.” Troops stayed in Little Rock for the entire school year, and in the spring of 1958, Central High had its first African American graduate.

But in September 1958, Faubus closed public schools to prevent their integration. Eisenhower expressed his “regret” over the challenge to the right of all Americans to a public education, but took no further action, despite what he had done a year earlier. There was no violence this time, and Eisenhower believed that he had a constitutional obligation to preserve public order, not to speed school desegregation. When Eisenhower left the White House, only 6 percent of African American students attended integrated schools.

Eisenhower's record included some significant achievements in civil rights. In 1957, he signed the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. The law provided new federal protection for voting rights. In most southern states, the great majority of African Americans simply could not vote, despite their constitutional right to do so, because of literacy tests, poll taxes, or other obstacles. Yet the legislation Eisenhower signed was weaker than the bill that he had sent to Capitol Hill. Southern Democrats secured an amendment that required a jury trial to determine whether a citizen had been denied his or her right to vote. In southern states, where African Americans could not serve on juries, such trials were not likely to ensure black access to the vote. In 1960, Eisenhower signed a second civil rights law, but it provided only small advances over the earlier law. The President also used his constitutional powers, where he believed that they were clear and specific, to advance desegregation, for example, in federal facilities in the nation's capital and to complete the desegregation of the armed forces begun during Truman’s presidency. In addition, Eisenhower appointed judges to federal courts whose rulings helped to advance civil rights.

Despite these actions, Eisenhower was only a limited supporter of civil rights. He urged advocates of desegregation to go slowly. He said that integration required a change in people's hearts and minds. Eisenhower was sympathetic to white southerners who complained about alterations in what they said was their way of life. He considered as extremists both those who tried to obstruct decisions of federal courts and those who demanded that they immediately enjoy the rights that the Constitution and the courts provided them. On only one occasion during his presidency—in June 1958—did Eisenhower meet with African American leaders. The President became irritated during the meeting when he heard appeals for more aggressive federal action to advance civil rights. He also failed to heed Martin Luther King, Jr.’s advice that he use the bully pulpit of the presidency to build popular support for racial integration. While Eisenhower’s actions mattered, so too did his failure to use his moral authority as President to advance the cause of civil rights. This issue, which divided the country in the 1950s, became even more difficult in the 1960s.